Q2-Grant-KOIN Center-4-21-10-Wm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Soros

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 23, Number 44, November 1, 1996 �ITffiInvestigation The secret financial network behind \vizard' George Soros by William Engdahl The dossier that follows is based upon a report released on . Following the crisis of the European Exchange Rate Oct. 1 by EIR's bureau 'in Wiesbaden, Germany, titled "A Mechanism of September 1992, when the Bank of England Profile of Mega-Speculator George Soros." Research was was forced to abandon efforts to stabilize the pound sterling, contributed by Mark Burdman, Elisabeth Hellenbroich, a little-known financial figure emerged from the shadows, to Paolo Raimondi, and Scott Thompson. boast that he had personally made over $1 billion in specula tion against the British pound. The speculator was the Hun Time magazine has characterized financier George Soros as garian-born George Soros, who spent the war in Hungary a "modem day Robin Hood," who robs from the rich to give under false papers working for the pro-Nazi government, to the poor countries of easternEurope and Russia. It claimed identifying and expropriating the property of wealthy fellow that Soros makes huge financial gains by speculating against Jews. Soros left Hungary afterthe war, and established Amer western central banks, in order to use his profits to help the ican citizenship after some years in London. Today, Soros is emerging post-communist economies of eastern Europe and based in New York, but that tells little, if anything, of who former Soviet Union, to assist them to create what he calls an and what he is. "Open Society." The Time statement is entirely accurate in Following his impressive claims to possession of a "Mi the first part, and entirely inaccurate in the second. -

American Jewish Philanthropy and the Shaping of Holocaust Survivor Narratives in Postwar America (1945 – 1953)

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “In a world still trembling”: American Jewish philanthropy and the shaping of Holocaust survivor narratives in postwar America (1945 – 1953) A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Rachel Beth Deblinger 2014 © Copyright by Rachel Beth Deblinger 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “In a world still trembling”: American Jewish philanthropy and the shaping of Holocaust survivor narratives in postwar America (1945 – 1953) by Rachel Beth Deblinger Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor David N. Myers, Chair The insistence that American Jews did not respond to the Holocaust has long defined the postwar period as one of silence and inaction. In fact, American Jewish communal organizations waged a robust response to the Holocaust that addressed the immediate needs of survivors in the aftermath of the war and collected, translated, and transmitted stories about the Holocaust and its survivors to American Jews. Fundraising materials that employed narratives about Jewish persecution under Nazism reached nearly every Jewish home in America and philanthropic programs aimed at aiding survivors in the postwar period engaged Jews across the politically, culturally, and socially diverse American Jewish landscape. This study examines the fundraising pamphlets, letters, posters, short films, campaign appeals, radio programs, pen-pal letters, and advertisements that make up the material record of this communal response to the Holocaust and, ii in so doing, examines how American Jews came to know stories about Holocaust survivors in the early postwar period. This kind of cultural history expands our understanding of how the Holocaust became part of an American Jewish discourse in the aftermath of the war by revealing that philanthropic efforts produced multiple survivor representations while defining American Jews as saviors of Jewish lives and a Jewish future. -

Faith and Fortune

FAITH AND FORTUNE By ANTHONY BIANCO - Businessweek jan 20 1997 Paul Reichmann: Talented, pious, driven--but not infallible Few businessmen have ever single-handedly wielded so much power to as calamitous effect as did Paul Reichmann, the mastermind of Olympia & York Developments Ltd. Founded by Paul and two of his brothers in Toronto in the late 1950s, Olympia & York at its peak had amassed $25 billion in assets, including 40 office towers and controlling stock holdings in Abitibi-Price Inc., Gulf Canada, and a half-dozen other major industrial corporations. Yet no one but a Reichmann ever owned stock or sat on O&Y's board. Through his unrelenting drive and outsize talent, Paul, the fifth of six siblings, came to dominate completely this most private of corporate empires. Reichmann's forte as a property developer was the contrarian masterstroke, whether it was erecting a 72-story tower in downtown Toronto when many considered the city already overbuilt or constructing the most distinguished addition to the New York City skyline in half a century--the World Financial Center--on a sandbar in the Hudson River. Paul was widely lauded as a commercial genius, ''an Einstein in a field that doesn't usually produce Einsteins,'' as one longtime colleague put it. Rarely has extreme commercial ambition come as decorously packaged as in the person of Paul Reichmann. Born in Vienna in 1930, he had resided in Paris, Antwerp, London, Tangier, Casablanca, and Jerusalem before his 24th birthday. With his shy smile, soft-spoken politesse, and elegantly funereal attire, the peripatetic Reichmann was a capitalist daredevil in the genteel guise of an undertaker. -

Institute of Jewish Affairs Additional Papers 4: General Sequences

223 MS 241 Institute of Jewish Affairs Additional Papers 4: general sequences MS 241/1 Numerical sequence MS 241/1/1 Arab-Israeli war - description of events prior to the 1967: Apr - Jul 1967 IJA 1A newspaper articles, press releases; the American Jewish Committee Foreign Affairs Department booklets `Reflections in Western Europe and Latin America to the situation in the Middle East' and `The Palestinian Liberation Organisation: an appraisal of its effect on Middle East tensions'; printed article; copies of the Jerusalem post and American Jewish Committee `Reports from.. Israel', Jul 1967 MS 241/1/2 Arab-Israeli war: newspaper articles, some in French, relating to Jun - Aug 1967 IJA 1B the war and to Israel's relations with other countries; United Nations paper on the situation in the Middle East IJA 10 United Nations: newspaper articles, some in French; JTA bulletins, 1967-70 MS 241/1/3 United Nations weekly summaries, bulletins all relating to Israel and the situation in the Middle East IJA 11 Arab statements: newspaper articles, some in German, Hebrew 1967 MS 241/1/4 script, on Arab countries reaction to the Arab-Israeli war IJA 12 Jews in Arab countries: newspaper articles; JTA bulletins; World 1967-8 MS 241/1/5 Jewish Congress correspondence, press releases, memorandums; notes; bulletins IJA 13 Arab activities outside the Middle East: newspaper cuttings; 1967 MS 241/1/6 bibliographical reference IJA 14 Public reaction to the Arab-Israeli war - United States of America: 1967-8 MS 241/1/7 newspaper articles, some in French and German; -

Authenticity, Identity and the Politics of Belonging: Sephardic Jews from North Africa and India Within the Toronto Jewish Community

AUTHENTICITY, IDENTITY AND THE POLITICS OF BELONGING: SEPHARDIC JEWS FROM NORTH AFRICA AND INDIA WITHIN THE TORONTO JEWISH COMMUNITY KELLY AMANDA TRAIN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN SOCIOLOGY YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO AUGUST 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-46016-0 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-46016-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

List of Canadians by Net Worth - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia List of Canadians by Net Worth from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

21/9/2014 List of Canadians by net worth - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia List of Canadians by net worth From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The following is a list of Canadians by net worth: Contents 1 Richest Canadians (2013 statistics) 2 Richest Canadians (2012 statistics) 3 Richest Canadians (2011 statistics) 4 Richest Canadians (2010 statistics) 5 Richest Canadians (2009 statistics) 6 References 7 External links Richest Canadians (2013 statistics) Updated November 23, 2013.[1] Legend Icon Description Has not changed since the 2012 ranking. Has increased since the 2012 ranking. Has decreased since the 2012 ranking. Net worth Home Sources of No. Name Age Residence (CAD) Province wealth Thomson David Thomson, 3rd Reuters, 1 Baron Thomson of $26.10 billion 56 Ontario Toronto, Ontario Woodbridge Co. Fleet and family Ltd George Weston Ltd., Loblaw 2 Galen Weston $10.40 billion 73 Ontario Toronto, Ontario Cos. Ltd, Holt Renfrew Arthur Irving, James New Saint John, New Irving Oil Ltd., 3 $7.85 billion — Irving, John Irving Brunswick Brunswick J.D. Irving Ltd. Edward Rogers III and Rogers 4 $7.60 billion 44 Ontario Toronto, Ontario http://en.wikipfeadmia.iolryg/wiki/List_of_Canadians_by_net_worth Communication1/s21 21/9/2014 List of Canadians by net worth - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia family Communications Vancouver, British Jim Pattison 5 Jim Pattison $7.39 billion 85 British Columbia Group Columbia Montreal, 6 Lino Saputo and family $5.24 billion 76 Quebec Saputo Inc. Quebec Montreal, Power Corp. of 7 Paul Desmarais $4.93 billion 86 Quebec Quebec Canada eBay Inc., Palo Alto, 8 Jeffrey Skoll $4.92 billion 48 Quebec Participant California Media James James Armstrong Winnipeg, 9 $4.45 billion — Richardson & Richardson and family Manitoba Manitoba Sons Ltd. -

Paul Reichmann Had a Dream. He and His Brothers Would Chal

3 FREE TRAINS OR FREE RIDERS? Reichmann's windfall train Paul Reichmann had a dream. He and his brothers would chal- lenge the oldest banking district in the world by building a financial centre on wasteland in the heart of London. They would compete with the City by offering the great financial houses accommodation in purpose-built skyscrapers. They had money aplenty including the biggest property empire in North America, which had amassed assets of $25 billion. Ingenuity was no problem: they had accomplished feats where other entrepren- eurs had feared to tread. Had they not built the World Financial Centre on a sandbar in New York's Hudson River? Daring was a family characteristic: in their youth, as Hitler tried to conquer Europe, from their enclave in Tangier they worked to defy the Nazis, launching covert mercy missions to keep alive the victims of the concentration camps. But without good transport links, their dream was not viable. Shrewdly, they acquired an 80-acre site on the Isle of Dogs in what was once the heart of a transport hub that knitted together a seafaring empire. The Reichmanns were offered a good deal by the government. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, in her bid to regenerate the area, turned Docklands into an enterprise zone. The brothers would be relieved of taxes on rents earned by 64 FREE TRAINS OR FREE RIDERS? their company, Olympia & York (O&Y). Here, out of the derelict docks, they could construct a masterpiece that combined the finest architecture with commercial vitality. They would lure the financiers from their mansions in the stockbroker belt to create a real estate for the 21st century. -

Northern Tigers: Building Ethical Canadian Corporate Champions

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2017-09 Northern Tigers: Building Ethical Canadian Corporate Champions Haskayne, Dick; Grescoe, Paul University of Calgary Press http://hdl.handle.net/1880/52226 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca NORTHERN TIGERS: Building Ethical DICK HASKAYNE WITH PAUL GRESCOE Canadian Corporate Champions With additional contributions from DEBORAH YEDLIN Dick Haskayne with Paul Grescoe With additional contributions from Deborah Yedlin ISBN 978-0-88953-406-3 BUILDING NORTHERN ETHICAL CANADIAN CORPORATE THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. Please support CHAMPIONS TIGERS this open access publication by requesting that your university A Memoir and a Manifesto purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy REVISED & UPDATED yourself. Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. -

Business Groups in Canada: Their Rise and Fall, and Rise and Fall Again

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES BUSINESS GROUPS IN CANADA: THEIR RISE AND FALL, AND RISE AND FALL AGAIN Randall Morck Gloria Y. Tian Working Paper 21707 http://www.nber.org/papers/w21707 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 November 2015 We are grateful for very helpful comments from Asli M. Colpan, Takashi Hikino, Franco Amatori, Tetsuji Okazak and participants in Kyoto University’s conference on Business Groups in Developed Economies and in the 2015 World Economic History Congress. We are grateful to the Bank of Canada for partial funding. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2015 by Randall Morck and Gloria Y. Tian. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Business Groups in Canada: Their Rise and Fall, and Rise and Fall Again Randall Morck and Gloria Y. Tian NBER Working Paper No. 21707 November 2015 JEL No. G3,L22,N22 ABSTRACT Family-controlled pyramidal business groups were important in Canada early in the 20th century, amid rapid catch-up industrialization, but largely gave way to widely held free-standing firms by mid- century. In the 1970s and early 1980s – an era of high inflation, financial reversal, unprecedented state intervention, and explicit emulation of continental European institutions – pyramidal groups abruptly regained prominence. -

November 28 — December 4, 2016 | Bloomberg.Com

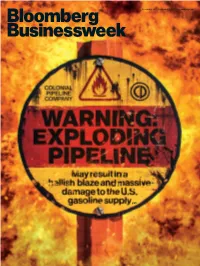

November 28 — December 4, 2016 | bloomberg.com p36 “Why didn’t I tell him to his face, immediately, that this was 1 misogynist, racist, and unprofessional? He was my p42 direct superior” “For any other “Putin’s a celebrity. Donald’s “I’m seeing people a celebrity. … He’s thinking, That smile now, clients of mine, purpose than guy’s a big dog. I’d rather be where I didn’t even know friends with him than one of these paperwork, I consider weaklings like Jeb Bush. That’s just they had teeth. Everyone myself an American” the way he thinks” I talk to is happy” p25 p50 p32 Cover Trail November 28 — December 4, 2016 How the cover gets made ① Opening Remarks Trump’s trajectory may follow those of other elected autocrats 6 “The story is about the Colonial Pipeline, specifically the implications Bloomberg View Don’t bully central banks • The trouble with the president-elect’s ISIS plan 8 of accidents like the explosion in Alabama.” Movers ▲ Weed floats on the NYSE ▼ Cooling Swiss watches and a warming North Pole 11 “The implications are generally good, right? Fire provides warmth, and Global Economics Lord knows it gets chilly this time of year. Trees just take up valuable Modi tries to drain the swamp 12 space, so it’s a quick and easy way to clear some land. And the oil The World Bank’s chief economist attacks the profession 13 industry is stable to the point of Europe braces for the next tremors from Italy 14 being boring. -

Building at What Cost?

David Hoffman בס"ד OH 244:1.2018 Building at What Cost? This teshuvah was passed on October 17, 2018, with a vote of nineteen in favor, two in opposition, and two abstained. Voting in favor: Rabbis Aaron Alexander, Pamela Barmash, Elliot Dorff, Baruch Frydman-Kohl, Susan Grossman, Reuven Hammer, David Hoffman, Jeremy Kalmanofsky, Jane Kanarek, Steven Kane, Jan Kaufman, Gail Labovitz, Amy Levin, Jonathan Lubliner, Daniel Nevins, Micah Peltz, Avram Reisner, Iscah Waldman, and Ellen Wolintz-Fields. Voting against: Rabbis David Booth and Joshua Heller. Abstaining: Rabbis Robert Scheinberg and Deborah Silver. Question: May a Jewish institution that has hired a non-Jewish contractor allow the contractors and their non-Jewish laborers to work on Shabbat or Yom Tov? This question was asked by the Senior administration of JTS at the beginning of their 21st Century building project in 2016. Answer: and demolishing in (בונה) We should first establish that activities connected to both building constitute primary categories of forbidden labor on Shabbat.1 Indeed, the (סותר) order to build main source in the Torah used to generate these 39 primary categories of prohibited activity is the physical construction of the Mishkan. These essential activities associated with the building of the Mishkan became the paradigmatic acts of constructive labor and, thus, were prohibited by the Rabbis on Shabbat. .from building on Shabbat מן התורה So, it is clear that a Jew is prohibited The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly provides guidance in matters of halakhah for the Conservative movement. The individual rabbi, however, is the authority for the interpretation and application of all matters of halakhah. -

Center for Real Estate Quarterly, Volume 4, Number 2

Portland State University PDXScholar Center for Real Estate Quarterly Center for Real Estate 5-1-2010 Center for Real Estate Quarterly, Volume 4, Number 2 Portland State University. Center for Real Estate Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/realestate_pub Part of the Real Estate Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Portland State University. Center for Real Estate, "Center for Real Estate Quarterly, Volume 4, Number 2" (2010). Center for Real Estate Quarterly. 15. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/realestate_pub/15 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Center for Real Estate Quarterly by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Center for Real Estate Quarterly & Urban Development Journal • 2nd Quarter 2010 ! ! ! •U.S. Demographics: • Leanne Lachman •Downtown Schools & R.E. Development • Gerard Mildner • Cooperative Housing in Portland: • Atha Mansoory •KOIN Center History: • Eugene Grant • Sustainable Containers: • Caroline Uittenbroek Cost-Effective Student Housing • Will Macht •Food Carts As Retail Real Estate: • April Chastain • Value of Questions & Questions of Value: Editor’s Urban Development Journal • Will Macht ––––– • ––––– • Office, Retail & Industrial Market Analyses • Kyle Smith • Multifamily & Housing Market Analyses • Scott Aster Center for Real Estate Quarterly & Urban Development Journal • 2nd Quarter 2010 Table of Contents: Page: 3. Editor’s Urban Development Journal Questions of Value & Value of Questions • Will Macht 15. U.S. Observations From Global Demographics • Leanne Lachman 23. Downtown Schools & Real Estate Development • Gerard Mildner 31.