The Revolutionary Guards' Looting of Iran's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi: Decision-Making and Factionalism in Iran’S Revolutionary Guard

The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi: Decision-Making and Factionalism in Iran’s Revolutionary Guard SAEID GOLKAR AUGUST 2021 KASRA AARABI Contents Executive Summary 4 The Raisi Administration, the IRGC and the Creation of a New Islamic Government 6 The IRGC as the Foundation of Raisi’s Islamic Government The Clergy and the Guard: An Inseparable Bond 16 No Coup in Sight Upholding Clerical Superiority and Preserving Religious Legitimacy The Importance of Understanding the Guard 21 Shortcomings of Existing Approaches to the IRGC A New Model for Understanding the IRGC’s Intra-elite Factionalism 25 The Economic Vertex The Political Vertex The Security-Intelligence Vertex Charting IRGC Commanders’ Positions on the New Model Shades of Islamism: The Ideological Spectrum in the IRGC Conclusion 32 About the Authors 33 Saeid Golkar Kasra Aarabi Endnotes 34 4 The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi Executive Summary “The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps [IRGC] has excelled in every field it has entered both internationally and domestically, including security, defence, service provision and construction,” declared Ayatollah Ebrahim Raisi, then chief justice of Iran, in a speech to IRGC commanders on 17 March 2021.1 Four months on, Raisi, who assumes Iran’s presidency on 5 August after the country’s June 2021 election, has set his eyes on further empowering the IRGC with key ministerial and bureaucratic positions likely to be awarded to guardsmen under his new government. There is a clear reason for this ambition. Expanding the power of the IRGC serves the interests of both Raisi and his 82-year-old mentor, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the supreme leader of the Islamic Republic. -

COUNCIL REGULATION (EU) No 267/2012 of 23 March 2012 Concerning Restrictive Measures Against Iran and Repealing Regulation (EU) No 961/2010 (OJ L 88, 24.3.2012, P

02012R0267 — EN — 09.07.2019 — 026.002 — 1 This text is meant purely as a documentation tool and has no legal effect. The Union's institutions do not assume any liability for its contents. The authentic versions of the relevant acts, including their preambles, are those published in the Official Journal of the European Union and available in EUR-Lex. Those official texts are directly accessible through the links embedded in this document ►B COUNCIL REGULATION (EU) No 267/2012 of 23 March 2012 concerning restrictive measures against Iran and repealing Regulation (EU) No 961/2010 (OJ L 88, 24.3.2012, p. 1) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 350/2012 of 23 April 2012 L 110 17 24.4.2012 ►M2 Council Regulation (EU) No 708/2012 of 2 August 2012 L 208 1 3.8.2012 ►M3 Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 709/2012 of 2 August 2012 L 208 2 3.8.2012 ►M4 Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 945/2012 of 15 October L 282 16 16.10.2012 2012 ►M5 Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 1016/2012 of 6 November L 307 5 7.11.2012 2012 ►M6 Council Regulation (EU) No 1067/2012 of 14 November 2012 L 318 1 15.11.2012 ►M7 Council Regulation (EU) No 1263/2012 of 21 December 2012 L 356 34 22.12.2012 ►M8 Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 1264/2012 of 21 December L 356 55 22.12.2012 2012 ►M9 Council Implementing Regulation (EU) No 522/2013 of 6 June 2013 L 156 3 8.6.2013 ►M10 Council Regulation (EU) No 517/2013 of 13 May 2013 L 158 1 10.6.2013 ►M11 Council Regulation (EU) No 971/2013 of 10 October 2013 -

Biden, Congress Should Defend Terrorism Sanctions Imposed on Iran

Research memo Biden, Congress Should Defend Terrorism Sanctions Imposed on Iran By Richard Goldberg, Saeed Ghasseminejad, Behnam Ben Taleblu, Matthew Zweig, and Mark Dubowitz January 25, 2021 During a Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing to consider Antony Blinken’s nomination for secretary of state, Blinken was asked whether he believed it is in America’s national security interest to lift terrorism sanctions currently imposed on Iran, including sanctions targeting Iran’s central bank, national oil company, financial sector, and energy sector. “I do not,” Blinken responded. “And I think there is nothing, as I see it, inconsistent with making sure that we are doing everything possible – including the toughest possible sanctions, to deal with Iranian support for terrorism.”1 Bipartisan support for terrorism sanctions targeting Iran goes back to 1984, when the United States first designated the Islamic Republic as a State Sponsor of Terrorism. Since then, every U.S. president2 – Republican or Democrat – and Congress have taken steps to reaffirm U.S. policy opposing Iran’s sponsorship of terrorism and tying sanctions relief to Iran’s cessation of terror-related activities. President Joe Biden has pledged to rejoin the 2015 Iran nuclear deal, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), if Iran returns to “strict compliance” with the agreement.3 Terrorism sanctions on Iran, however, should not be lifted, even if the Biden administration opts to return to the deal, unless and until Iran verifiably halts its sponsorship of terrorism. This memorandum provides an overview of Iran’s past and ongoing involvement in terrorism-related activities, a review of longstanding bipartisan congressional support for terrorism sanctions on Iran, and a list of terrorism sanctions currently imposed on Iran that should not be lifted. -

The Intelligence Organization of the IRGC: a Major Iranian Intelligence Apparatus Dr

רמה כ ז מל ו תשר מה ו ד י ע י ן ( למ מ" ) רמה כרמ כ ז ז מל מה ו י תשר עד מל מה ו ד ו י ד ע י י ע ן י ן ו רטל ( למ ו מ" ר ) כרמ ז מה י עד מל ו ד י ע י ן ו רטל ו ר The Intelligence Organization of the IRGC: A Major Iranian Intelligence Apparatus Dr. Raz Zimmt November 5, 2020 Main Argument The Intelligence Organization of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) has become a major intelligence apparatus of the Islamic Republic, having increased its influence and broadened its authorities. Iran’s intelligence apparatus, similar to other control and governance apparatuses in the Islamic Republic, is characterized by power plays, rivalries and redundancy. The Intelligence Organization of the IRGC, which answers to the supreme leader, operates alongside the Ministry of Intelligence, which was established in 1984 and answers to the president. The redundancy and overlap in the authorities of the Ministry of Intelligence and the IRGC’s Intelligence Organization have created disagreements and competition over prestige between the two bodies. In recent years, senior regime officials and officials within the two organizations have attempted to downplay the extent of disagreements between the organizations, and strove to present to domestic and foreign audience a visage of unity. The IRGC’s Intelligence Organization (ILNA, July 16, 2020) The IRGC’s Intelligence Organization, in its current form, was established in 2009. The Organization’s origin is in the Intelligence Unit of the IRGC, established shortly after the Islamic Revolution (1979). -

Com(2010)459 En.Pdf

EN EN EN EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 31.8.2010 COM(2010) 459 final 2010/0240 (NLE) Proposal for a COUNCIL REGULATION (EU) No …/2010 on restrictive measures against Iran and repealing Regulation (EC) No 423/2007 (presented jointly by the Commission and the High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy) EN EN EXPLANATORY MEMORANDUM (1) On 26 July 2010, the Council approved Decision 2010/413/CFSP confirming the restrictive measures taken since 2007 and providing for additional restrictive measures against Iran in order to comply with UN Security Council Resolution 1929 (2010) and accompanying measures as requested by the European Council in its Declaration of 17 June 2010. (2) These restrictive measures comprise in particular additional restrictions on trade in dual-use goods and technology and equipment which might be used for internal repression, restrictions on trade in key equipment for, and on investment in, the Iranian oil and gas industry, restrictions on Iranian investment in the uranium mining and nuclear industry, restrictions on transfers of funds to and from Iran, restrictions concerning the Iranian banking sector, restrictions on Iran’s access to the insurance and bonds markets of the Union and restrictions on providing certain services to Iranian ships and cargo aircraft. (3) The Council also provided for additional categories of persons to be made subject to the freezing of funds and economic resources and certain other, technical amendments to existing measures. (4) The restrictive measures concerning dual-use goods should be broadened to cover all goods and technology of Annex I to Regulation (EC) No 428/2009, with the exception of certain items in its Category 5. -

Spotlight on Iran (April 18, 2021 – May 2, 2021)

רמה כ ז מל ו תשר מה ו ד י ע י ן ( למ מ" ) כרמ ז מה י עד מל ו ד י ע י ן ו רטל ו ר Spotlight on Iran April 18, 2021` – May 2, 2021 Author: Dr. Raz Zimmt Overview Iranian threats toward Israel: the chief of staff of Iran’s Armed Forces threatened with Iranian retaliation if Israel persists in striking Iranian interests in Syria and at sea. In addition, the commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) threatened that Iran will respond to any “evil action” by the “Zionists” against it, with a force equal to the blow it is dealt, or even with greater force. The Russian news agency Sputnik reported that Iran, Russia, and Syria reached an agreement that Russian warships will accompany Iranian tankers ferrying oil and natural gas to Syria through the Suez Canal and the Mediterranean Sea. In late April, Mohammad Javad Zarif, the Iranian Minister of Foreign Affairs, arrived for a two-day visit in Iraq, during which he met with senior Iraqi government officials, the head of the Shia political blocs and senior officials of the Kurdistan Regional Government in northern Iraq. Throughout the visit, Zarif discussed bilateral ties and developments in the region with the senior Iraqi officials. A few days prior to Zarif’s visit in Baghdad, the Iranian deputy minister of defense also visited Baghdad and met with the Iraqi minister of interior and with the commander of the Popular Mobilization Units (al-Hashd al-Shaabi, the umbrella force of the Shia militias operating in Iraq). -

Credit Rating Companies with Multi-Criteria Decision Making Models and Artificial Neural Network Model

J. Basic. Appl. Sci. Res., 3(5)536-546, 2013 ISSN 2090-4304 Journal of Basic and Applied © 2013, TextRoad Publication Scientific Research www.textroad.com Credit Rating Companies with Multi-Criteria Decision Making Models and Artificial Neural Network Model Maghsoud Amiri1, Mehdi Biglari Kami*2 1Allameh Tabatabaei University, Tehran, Iran 2Institute of Higher Education Raja, Qazvin, Iran ABSTRACT This research seeks to develop a procedure for credit rating of manufacturing corporations accepted in Tehran stock exchange. So, financial ratios of 181 manufacturing corporations in Iran stock exchange were extracted, These ratios reflect the financial ability to pay principal and interest of loan. Initially, fifty selected corporations ranked by using TOPSIS method based on financial ratios by using of Shannon entropy will be obtained the weight of each criterion. In addition, classification credit with neural network has compared by logistic regression; and finally, each had more credibility, used to rank all corporations. Then all corporations have classified by neural network. Finally, the neural network classification results compared with the expert classification. About 95% of the neural network data has placed in its respective class, and the data results indicated a robust neural network classification based on training. The neural network offered far more accurate answer than the logistic regression in this classification. At the end, the neural network ranked all corporations, and neural network classification results compared with expert opinion, showing that the neural network classification was very close to an expert opinion. KEYWORDS: Financial ratios; TOPSIS; Artificial neural network; Logistic regression. INTRODUCTION Today, the credit industry plays an important role in the economy of corporations. -

The Political Economy of the IRGC's Involvement in the Iranian Oil and Gas Industry

The Political Economy of the IRGC’s involvement in the Iranian Oil and Gas Industry: A Critical Analysis MSc Political Science (Political Economy) Thesis Research Project: The Political Economy of Energy University of Amsterdam, Graduate School of Social Sciences 5th June 2020 Author: Hamed Saidi Supervisor: Dr. M. P. (Mehdi) Amineh (1806679) Second reader: Dr. S. (Said) Rezaeiejan [This page is intentionally left blank] 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................ 3 Abstract ............................................................................................................................................... 6 Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................... 7 Maps ................................................................................................................................................ 8 List of Figures and Tables ................................................................................................................. 10 List of Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 11 I: RESEARCH DESIGN .................................................................................................................................... 13 1.1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ -

How the Israel Defense Forces Might Confront Hezbollah

JEMEAA - VIEW How the Israel Defense Forces Might Confront Hezbollah DR. EHUD EILAM The inevitability of another war between Israel and the Hezbollah terrorist organization seems nearly certain; however, at present, neither belligerent in this longstanding feud desires immediate conflict.1 The two sides confronted each other in Lebanon in the 1980s and in the 1990s, until the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) withdraw from that country in 2000, concluding a campaign that had come to be known as the “Israeli Vietnam.” In 2006, war erupted between the two combatants again, lasting a mere 34 days.2 That war ended in a draw. Since then, the two sides have been preparing for another round. In recent years, the IDF has been adapting to fight hybrid forces such as Hez- bollah and Hamas, instead of focusing on the militaries of Arab states like Syria and Egypt. This transformation has been a challenging process, although overall the risk of state- on- state war is much lower for Israel in comparison with the era of high intensity wars (1948–1982). Even a coalition of hybrid forces together with the Syrian military in its current strength does not pose an existential threat to Israel, in contrast to the danger of an alliance between Arab states from the 1950s to the 1970s. However the IDF still must be ready for major combat.3 Since 2012, Israel has carried out hundreds of sorties in Syria, aiming to reduce as much as possible the delivery of weapons to Hezbollah in Lebanon.4 Israel avoided directly attacking Hezbollah in Lebanon, although some in Israel sup- port a preemptive strike against the terrorist organization.5 There is a low proba- bility that Israel will conduct a massive surprise offensive against Hezbollah due to its cost and the uncertainty of the outcome. -

Verordnung Über Massnahmen Gegenüber Der Islamischen Republik Iran Vom 19

946.231.143.6 Verordnung über Massnahmen gegenüber der Islamischen Republik Iran vom 19. Januar 2011 (Stand am 17. April 2012) Der Schweizerische Bundesrat, gestützt auf Artikel 2 des Embargogesetzes vom 22. März 20021 (EmbG), verordnet: 1. Abschnitt: Begriffe Art. 1 In dieser Verordnung bedeuten: a. Gelder: finanzielle Vermögenswerte, einschliesslich Bargeld, Schecks, Geldforderungen, Wechsel, Geldanweisungen oder andere Zahlungsmittel, Guthaben, Schulden und Schuldverpflichtungen, Wertpapiere und Schuldti- tel, Wertpapierzertifikate, Obligationen, Schuldscheine, Optionsscheine, Pfandbriefe, Derivate; Zinserträge, Dividenden oder andere Einkünfte oder Wertzuwächse aus Vermögenswerten; Kredite, Rechte auf Verrechnung, Bürgschaften, Vertragserfüllungsgarantien oder andere finanzielle Zusagen; Akkreditive, Konnossemente, Sicherungsübereignungen, Dokumente zur Verbriefung von Anteilen an Fondsvermögen oder anderen Finanzressour- cen und jedes andere Finanzierungsinstrument für Exporte; b. Sperrung von Geldern: die Verhinderung jeder Handlung, welche die Ver- waltung oder die Nutzung der Gelder ermöglicht, mit Ausnahme von nor- malen Verwaltungshandlungen von Finanzinstituten; c. Geldtransfer: jede Transaktion, die im Namen eines Auftraggebers über ei- nen Zahlungsverkehrsdienstleister auf elektronischem Weg mit dem Ziel ab- gewickelt wird, einem Begünstigten bei einem Zahlungsverkehrsdienstleister einen Geldbetrag zur Verfügung zu stellen, unabhängig davon, ob Auftrag- geber und Begünstigter dieselbe Person sind; d. iranische Bank: 1. eine Bank mit Sitz in der Islamischen Republik Iran (Iran), einschliess- lich der iranischen Zentralbank, 2. Zweigniederlassungen und Tochtergesellschaften einer Bank mit Sitz in Iran, AS 2011 383 1 SR 946.231 1 946.231.143.6 Aussenhandel 3. eine Bank, die ihren Sitz nicht in Iran hat, aber von Personen oder Organisationen mit Sitz in Iran kontrolliert wird; e. iranische Person oder Organisation: 1. der iranische Staat sowie jede Behörde dieses Staates, 2. jede natürliche Person mit Aufenthaltsort oder Wohnsitz in Iran, 3. -

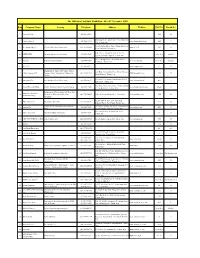

Row Company Name Activity Telephone Address Website Hall No Booth No

The 10th Auto Parts Int,l. Exhibition - 16 to 19 November 2015 Row Company Name Activity Telephone Address WebSite Hall No Booth No 1 Abarashi Group (021)36466786 31B 38 D46 Golgasht St., Golzar Ave, Parand Industrial 2 Abzar Andisheh (021)56419014 www.abzarandisheh.com 40B 7 City, Tehran- Iran No.120, Kalhor Blvd, Shahre Ghods, 20th km of 3 Ace Engineering Co Electrical Auto Part Manufacturer (021)46884888-9 www.ACE.IR 40B 16 Karaj Old Road, Tehran, Iran Unit 2, No. 4, Koopayeh Alley, Before the 4 ADIB IMENi Garment industry and advertising (021)55380846 Open Area South 31 Qazvin Sq, South Kargar St, Tehran, Iran No. 17, Dastgheib Ave, West Shahed Blvd., 5 Agradad Industrial Automatic Door (021)44588684 www.agradad.com Open Area South 31 Tehransar, Tehran, Iran 6 AL.TECH. (021)26760992 www.dinapart.com 6 38 Manufactur of Types of Steel Parts by hot Sarir Bldg., Peykanshahr Exit,15th km Tehran- 7 Alborz Forging IND forging method, Auto Gearbox, Suspension (021)44784191-5 www.forgealborz.com 40B 29 Karaj Highway, Tehran- Iran Chassis No. 18 & 19, Next to the Gas Station, West 15 8 Aluminium Faz Car Aluminium Parts (Die Casting) (021)55690137 www.aluminiumfaz.ir 40A 3 Khordad St., Tehran, Iran First Floor, No.7, Zahiroleslam Alley, Iranshahr 9 Alvand Electronic Dana Vehicle Tracking, kinds of electronic boards (021)88313640 www.alvandelectronic.com 20-22 16 St., Taleghani Ave., Tehran- Iran Production of different kind of oil filters, Fuel Aman Filter Industrial 10 filters & Air filters for light & heavy (021)77167003-5 Unit 6, 3rd Floor, Piroozi Ave, Tehran, Iran www.amanfilter.com 31B 28 Production Group automobile No.207, 208- F, Sarv 24 St, Nasirabad 11 Aman Ghate Kar Automobile spare parts (021)56390795 20-22 20 Industrial Town, Saveh Road, Tehran, Iran Manufacturing Auto suspension & steering 1st Eastern 20 Meter St., Tabriz Exhibition old 12 Amirnia Co. -

Transport Equipments, Part & Accessories

• Transport Equipments, Part & Accessories Aircrafts Motorcycles Automotive body parts Oil seals Automotive conditioners Pistons Automotive cylinders Pumps Automotive door locks Safety mirrors & belts Automotive fuel parts Sheet glass Automotive leaf springs Shock absorbers Automotive lights Steering wheels, Wheel alignment Automotive luxury parts Traffic equipments Automotive parts, Spare parts Vehicles Automotive rad iators misc . Automotive services Axles, Gearboxes Automotive Ball bearings, a-rings Bicycles Boats, Ships, & Floatings Brake systems Buses, Minibuses, Vans Clutches, Clutch facings Engines Garage equipments References:Iran Tpo Exporters Data Bank,Exemplary Exporters Directory Iran TradeYellowpages, Iran Export Directory www.tpo.ir ALPHA KHODRO CO www.armco-group.com Tel:(+98-21) 8802St57. 88631750 Head Office: Alborz St, Comer of Main •CHAPTERA MD:Farshad Fotouhi Fax: (+98-21) 8802St43. 88737190 ABGINEH CO Andishe St. Beheshti St Tehran Activity: Heat Exchangers. Automotive Email: [email protected] Head Office: No 34. 7th St. S J Asad Abadi Tel: (+98-21) 88401280 Radialors [M-E-I] URL: www.aice-co.com St .14336. Tehran Fax: (+98-21) 88St7137 MD:Mohammad Mehdi Firouze Tel: (+98-21) 88717002. 88717004, Email: [email protected] ARVAND WHEEL CO.(DAACH) Activity: Automotive Parts [M-I] 88717007 MD:Majid Alizade Head Office: No 55, 20th St. After Kouye Activity: Motorcycles [M] Fax: (+98-21) 88715328 Daneshgah, North Kargar St, 1439983693. AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRIES Factory: (+98-282) 2223171-3 Tehran DEVELOPMENT CO. Email: [email protected] Tel: (+98-21) 88009901 Head Office: Zaman St, Opposite Mega URL: www.abglneh.com AMIRAN MOTORCYCLE CO Fax: (+98-21) 88010832.88330737 Motor. 16th Km of Karaj Ex-Rd. Tehran Head Office: 3rd FI No 2.Corner of East 144th MD:Mohsen Mazandrani Factory: (+98-391) 822St70-80 Tel: (+98-21) 66284211-5 St Tehran Pars 1st Sq , Tehran Registered in Tehran Stock Exchange Email: [email protected] Fax: (+98-21) 66284210 Tel: (+98-21) 77877047 Activity: Laminated Glass Sheets.