Participation by the Public in the Federal Judicial Selection Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Sessions of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations

S. Prt. 107–84 EXECUTIVE SESSIONS OF THE SENATE PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT OPERATIONS VOLUME 4 EIGHTY-THIRD CONGRESS FIRST SESSION 1953 ( MADE PUBLIC JANUARY 2003 Printed for the use of the Committee on Governmental Affairs U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 83–872 WASHINGTON : 2003 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Jan 31 2003 21:53 Mar 31, 2003 Jkt 083872 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 E:\HR\OC\83872PL.XXX 83872PL COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS 107TH CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION JOSEPH I. LIEBERMAN, Connecticut, Chairman CARL LEVIN, Michigan FRED THOMPSON, Tennessee DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii TED STEVENS, Alaska RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois SUSAN M. COLLINS, Maine ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey GEORGE V. VOINOVICH, Ohio MAX CLELAND, Georgia THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah MARK DAYTON, Minnesota JIM BUNNING, Kentucky PETER G. FITZGERALD, Illinois JOYCE A. RECHTSCHAFFEN, Staff Director and Counsel RICHARD A. HERTLING, Minority Staff Director DARLA D. CASSELL, Chief Clerk PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS CARL LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii, SUSAN M. COLLINS, Maine RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois TED STEVENS, Alaska ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey GEORGE V. VOINOVICH, Ohio MAX CLELAND, Georgia THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah MARK DAYTON, Minnesota JIM BUNNING, Kentucky PETER G. FITZGERALD, Illinois ELISE J. BEAN, Staff Director and Chief Counsel KIM CORTHELL, Minority Staff Director MARY D. -

2016 NLG Honorees

ww.nlg.org/conventionLearn more! Dozens of social justice oriented CLEs, workshops, panels and events on movement law! Honoring Soffiyah Elijah • Albert Woodfox • Michael Deutsch • Audrey Bomse Javier Maldonado • Noelle Hanrahan • Emily Bock • With Keynote Speaker Elle Hearns Co-Sponsored by NYU School of Law Public Interest Law Center* | National Lawyers Guild Foundation *Current NYU Law students and 2016 graduates will receive complimentary convention registration New York City & the Origins of the Guild The New York City Chapter is thrilled to welcome you to the 2016 NLG Convention. It has been a long while since the convention was last held in NYC. Through the generous co-sponsorship of the Public Interest Law Center at NYU School of Law, including Dean Trevor Morrison, Assistant Dean for Public Service Lisa Hoyes and Prof. Helen Hershkoff, our conference this year has access to wonderful Greenwich Village classroom meeting facilities and dormitory housing. Our sincere thanks to NYU for partnering with us. 2016 is turning out to be a turning point year for law in our country. Thus, we feel especially privileged to engage allies from social justice organizations in New York and the East Coast in discussions about the future of crucial progressive issues. The Supreme Court is in the balance for the next generation; public figures project a vision which is less fair, less tolerant, and downright racist. Shocking as these times are, this is when the NLG needs to be at its best to defend peoples’ rights. Hard times have often brought out the best in the NLG. From the Guild’s early beginnings, when it was formed as a racially and ethnically integrated alternative to the segregated American Bar Association, NLG-NYC members have played an integral role. -

NLG #Law4thepeople Convention

NLG #LAW4THEPEOPLE CONVENTION August 2016 New York City NYU School of Law 1 Cover: Guild contingent at disarmament rally, New York City, 1982. From left: Teddi Smokler, Stanley Faulkner, Ned Smokler, Peter Weiss, Deborah Rand, Harry Rand, Victor Rabinowitz, Gordon Johnson, unidentified. Photo curated as part of the NLG's 50th anniversary photo spread by Tim Plenk, Joan Lifton, and Jonathan Moore in 1987. Layout and Design by Tasha Moro WELCOME TO NEW YORK! Dear fellow Guild members, supporters, and allies: On behalf of the New York City Chapter, welcome to the NLG’s Annual Banquet. Each year convention participants pause for an evening of celebration, to savor reflection with like-minded legal activists and recommit to the work of justice. We hope you have enjoyed convening on campus, which was once the traditional format for NLG conventions, and that you have found the facilities amenable to productive work. Please join us in heartfelt thanks to New York University School of Law’s Public Interest Law Center (PILC) for co-hosting the Convention, including Dean Trevor Morrison, Assistant Dean for Public Service Lisa Hoyes, Prof. Helen Hershkoff, NYU Law’s Events Coordinator Josie Haas, Alesha Gooden, Nikita Chardhry, Ashley Martin, and Jerry Roman of NYU’s Office of Housing Services. A special salute goes to Lisa Borge, Programs Manager of the NYU Law Public Interest Law Center. The New York City Chapter has been fortunate to have generations of members who have worked in support of movements for social justice. They have founded projects that have gone on to become national programs or nonprofit organizations, and started law collectives, movement offices, and public interest law firms. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS 39419 Mr

December 1, 1970 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 39419 Mr. MILLS: Committee on Ways and By Mr. KASTENMEIER: By Mr. KUYKENDALL (for himself, Mr. Means. H.R. 19567. A blll to continue until H.R. 19884. A blll to provide relief in pat GROVER, Mr. CLEVELAND, Mr. DON H. the close of September 30, 1973, the Inter ent and trademark cases affected by the CLAUSEN, Mr. MCEWEN, Mr. DUNCAN, national Coffee Agreement Act of 1968; with emergency situation in the U.S. Postal Serv Mr. SCHWENGEL, Mr. DENNEY, Mr. amendments (Rept. No. 91-1641). Referred ice which began on March 18, 1970; to the McDONALD of Michigan, Mr. HAM to the Committee of the Whole House on the Committee on the Judiciary. MERSCHMIDT, Mr. BROCK, and Mr. State of the Union. By Mr. McMILLAN (for himself and ANDERSON of Tennessee) : Mr. STAGGERS: Committee on Interstate Mr FuQUA): H.R. 19891. A bill to name a Federal build and Foreign Commerce. S. 2162. An act to H.R. 19885. A bill to provide additiOIIlal ing in Memphis, Tenn., for the late Clifford provide for special packaging to protect chil revenue for the DIStrict of Columbia, and for Davis; to the Committee on Public Works. dren from serious personal injury or serious other purposes; t~ the Committee on the By Mr. PEPPER: illness resulting from handling, using, or in District of Columbia. H.R. 19892. A bill to declare a portion of gesting household substances, and for other By Mr. PELLY: the Oleta River in Dade County, Fla., non purposes; with an amendment (Rept. -

Executive Sessions of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations

S. Prt. 107–84 EXECUTIVE SESSIONS OF THE SENATE PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT OPERATIONS VOLUME 5 EIGHTY-THIRD CONGRESS SECOND SESSION 1954 ( MADE PUBLIC JANUARY 2003 Printed for the use of the Committee on Governmental Affairs VerDate Jan 31 2003 00:20 Apr 16, 2003 Jkt 083873 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 6011 E:\HR\OC\83873PL.XXX 83873PL EXECUTIVE SESSIONS OF THE SENATE PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT OPERATIONS—VOLUME 5 VerDate Jan 31 2003 00:20 Apr 16, 2003 Jkt 083873 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 E:\HR\OC\83873PL.XXX 83873PL S. Prt. 107–84 EXECUTIVE SESSIONS OF THE SENATE PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT OPERATIONS VOLUME 5 EIGHTY-THIRD CONGRESS SECOND SESSION 1954 ( MADE PUBLIC JANUARY 2003 Printed for the use of the Committee on Governmental Affairs U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 83–873 WASHINGTON : 2003 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Jan 31 2003 00:20 Apr 16, 2003 Jkt 083873 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 E:\HR\OC\83873PL.XXX 83873PL COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS 107TH CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION JOSEPH I. LIEBERMAN, Connecticut, Chairman CARL LEVIN, Michigan FRED THOMPSON, Tennessee DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii TED STEVENS, Alaska RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois SUSAN M. COLLINS, Maine ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey GEORGE V. -

The National Lawyers Guild: Thomas Emerson and the Struggle for Survival

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 38 Issue 4 Article 17 1988 The National Lawyers Guild: Thomas Emerson and the Struggle for Survival Victor Rabinowitz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Victor Rabinowitz, The National Lawyers Guild: Thomas Emerson and the Struggle for Survival, 38 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 608 (1988) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol38/iss4/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD: THOMAS EMERSON AND THE STRUGGLE FOR SURVIVAL Victor Rabinowitz* "THE NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD was born in revolt-a revolt that embraced the entire intellectual life of the times."' Indeed, almost all of the 50-year history of the Guild has been tu- multuous. It has suffered from vigorous attacks, almost since its inception, from the Dies Committee, from the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), from the Federal Bureau of In- vestigation and from the Department of Justice. These attacks have been unremitting and backed by the full resources of a hostile gov- ernment establishment. Along with such government action, and in part because of it, the Guild has endured a series of deep-seated differences within its own ranks, resulting in periodic waves of resig- nation from membership. -

Claudia Jones Part 8 of 10

. J *» - . _ V 92 _ . -. _ _ _._-_- :-...L_.-.- >...,..--.--.-.....---.._=_ 4.».-Q-Q-as . _-..... .. i I !9 __92.4 "'i"92I * l "#1:" g'~'*">-- -'- '"IA" 1r."*. - " :1 " T '¢7"~-1,6."- '- ' . i "'_,.+-_-1 H. t~fl'.'- ~ .-- .. -' '., H .". W. __M 1"". u. L _ - " ll - A W92 §§J5oTl921"'92*'. -- ~-- _-__-- "d-"LI-9 - J!-»___hf; ..-.n'- Kw 'K.92*-I---'-.-*M; _'+ , ."1».5. *_-_ "_ _' "'--.- '1'.» - - - P _!-_ ,'._ : -V 'u.~ __ 1- _ ..,-_l. 5: .'_-.-'92I , - e -. ' ;__ ___- __ _ . "" - 1' - , . O '--*: ix" 92| . .... - i-'e"921'-'-. ~- "K. ,.-- "_*"-J, I H '__ ' NI 1QQ-l8676m.!|, " r. _""Tj "L{,1];ef'_L_;¢u~ N P a f*§Q;Z,J;;§;;'ég5- .-' - .»- 1- r J1. .9 - an ii? '_ =.- ~:~, ."-92'I-u92_ . c I 1 _f-if-I. It is noted that the Civil Rights Congress was cited by the Attorney General as coming within the purview of Executive . it, --»i . .e,- .~ Ki - O ' -e =~= e-"P = ; J § _.'April On 10, 1952, the~se11,"u¢rkse* gag. as 8,, f1}: =- columns 2and 3, contained an article entitled CLAUDIA.JOHES.#1fI?_, Inspired by Detroit Hatred of Smith Act". The article stated J' it" 3'1 1 "Hhe maesesof the American PeoPleare in a mood 3-even s==wéi¢?%*?l§ I r Americans during the Alien and Sedition Acts -- to nullify the "; " . -

THE HAMM. LAWYERS GUILD Headquarters for the NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD Have Been Moved from New

Published monthly by the MINUTEMEN, P.O. Box 68, Norborne, Mo. Subscription rate, $5.00 per year We guarantee that all law suits filed against this news letter will be settled out of court. WORDS WON'T WIN- ACTION WILL July 1, 1964 THE HAMM. LAWYERS GUILD Headquarters for the NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD have been moved from New . York to Detroit and Ernest Goodman, of the law firm of Goodman, Crockett, Eden, Robb and Philo, has been elected national Guild president. The Guide To Subversive Organizations and Publications, published in December 1961 by the U. S. Government Printing Office (Price 70 cents), offers the following pertinent information regarding the NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD: 1. Cited as a Communist front. (Special Committee on Un-American Activities, House Report 1311 on the CIO Political Action Committee, March 29, 1944, p. 149). 2. Cited as a Communist front which "is the foremost legal bulwark of the Communist Party, its front organizations, and controlled unions" and which "since its inception has never failed to rally to the legal defense of the Communist Party and individual members thereof, including known espionage agents." (Committee on Un-American Activities, House Report 3123 on the National Lawyers Guild, September 21, 1950, originally released Sept. 17, 1950). 3. "To defend the cases of Communist lawbreakers, fronts have been devised making special appeals in behalf of civil liberties and reaching out far beyond the confines of the Communist Party it- self. Among these organizations are the ***National Lawyers Guild: When the Communist Party itself is under fire these offer a bulwark of protection." .(Internal Security Subcommittee of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Handbook for Americans, S.Doc. -

People's World Photograph Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8pz5fz6 No online items Finding Aid to the People's World Photograph Collection Finding aid prepared by Labor Archives staff. Labor Archives and Research Center 2012, Revised 2017 San Francisco State University 1630 Holloway Ave San Francisco 94132-1722 [email protected] URL: http://www.library.sfsu.edu/larc Finding Aid to the People's World larc.pho.00091986/073, 1990/013, 1992/003, 1992/049, 1 Photograph Collection 1994/037, 2011/015 Title: People's World Photograph Collection Date (inclusive): 1856-1992 Date (bulk): 1930-1990 Creator: People's World. (San Francisco, Calif.). Extent: 22 cubic ft. (45 boxes) Call number: larc.pho.0009 Accession numbers: 1986/073, 1990/013, 1992/003, 1992/049, 1994/037, 2011/015 Contributing Institution: Labor Archives and Research Center J. Paul Leonard Library, Room 460 San Francisco State University 1630 Holloway Ave San Francisco, CA 94132-1722 (415) 405-5571 [email protected] Abstract: The People's World Photograph Collection consists of approximately 6,000 photographs used in People's World, a grassroots publication affiliated with the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA). The photographs, along with a small selection of cartoons and artwork, highlight social and political issues and events of the 20th century, with the views of the newspaper aligning with the CPUSA's policies on topics such as civil rights, labor, immigration, the peace movement, poverty, and unemployment. The photographs, the bulk of which span the years 1930 to 1990, comprise predominantly black and white prints gathered from a variety of sources including government agencies, photographic studios, individual photographers, stock image companies, and news agencies, while many of the cartoons and artwork were created by People's World editor and artist Pele deLappe. -

1955 Journal

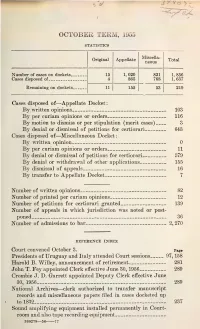

OCTOBER TERM, 1955 STATISTICS Miscella- Original Appellate Total neous Number of Gases on dockets 15 1, 020 821 1, 856 Cases disposed of 4 865 768 1, 637 Remaining on dockets. 11 155 53 219 Cases disposed of—Appellate Docket: By written opinions 103 By per curiam opinions or orders 116 By motion to dismiss or per stipulation (merit cases) 3 By denial or dismissal of petitions for certiorari 64& Cases disposed of—Miscellaneous Docket : By written opinion 0 By per curiam opinions or orders 11 By denial or dismissal of petitions for certiorari 579 By denial or withdrawal of other applications 155 By dismissal of appeals 16 By transfer to Appellate Docket 7 Number of written opinions 82 Number of printed per curiam opinions 12 Number of petitions for certiorari granted 139 Number of appeals in which jurisdiction was noted or post- poned 36 Number of admissions to bar 2, 270 REFERENCE INDEX Court convened October 3. Page Presidents of Uruguay and Italy attended Court sessions 97, 158 Harold B. Willey, announcement of retirement 281 John T. Fey appointed Clerk effective June 30, 1956 289 Crombie J. D. Garrett appointed Deputy Clerk effective June 30, 1956 289 National Archives—clerk authorized to transfer manuscript records and miscellaneous papers filed in cases docketed up to 1832 237 Sound amplifying equipment installed permanently in Court- room and also tape recording equipment 360278—56 77 Attorney : Page Motion for reinstatement of Norman J. Griffin granted and order of disbarment vacated (300 Misc.) 42 Disbarment of Orille C. Gaudette (336 Misc.) 103, 154 Change of name 88 Counsel appointed (489, 460, 714) 81, 119, 163 Special Master, compensation awarded (10 Orig.) 282 Rules of Criminal Procedure amended and reported to Con- gress 202 Opinion amended (23) 258 Orders and judgments amended (406 O. -

1963 Journal

: : .. OCTOBER TERM, 1963 STATISTICS Original Appellate Miscella- Total neous Number of cases on dockets. _ 9 1, 238 1, 532 2, 779 Cases disposed of 2 1, 036 1, 374 2, 412 Remaining on dockets 7 202 158 367 Cases disposed of—Appellate Docket By written opinions 123 By per curiam opinions or orders 180 By motion to dismiss or per stipulation (merits cases) 0 By denial or dismissal of petitions for certiorari 733 Cases disposed of—Miscellaneous Docket By written opinions 0 By denial or dismissal of petitions for certiorari 1, 093 By denial or withdrawal of other applications 180 By granting of other applications 1 By per curiam dismissal of appeals 30 By other per curiam opinions or orders 59 By transfer to Appellate Docket 11 Number of written opinions 111 Number of printed per curiam opinions 20 Number of petitions for certiorari granted (Appellate) 118 Number of appeals in which jurisdiction was noted or postponed 31 Number of admissions to bar 3, 184 REFERENCE INDEX GENERAL: Court convened October 7, 1963 and adjourned June 22, 1964. Members of Court attended funeral of President Kennedy (not in session) (November 25, 1963) Court attended Joint Session of Congress to hear President Johnson's Message following President Kennedy's death (not in session) (November 27, 1963) : : — II GENEEAL—Continued Page Douglas, J., Eemarks by Attorney General and response by Chief Justice on occasion of completion of 25 full terms as Associate Justice (April 20, 1964) 271 Eeed, J., Designated and assigned to U.S. Court of Claims 2 Wyatt, Walter, Appointed -

Nancy Sterns • Natasha Lycia Ora Bannan and Law Student Recognition Awardee Kyle Barron

81ST ANNIVERSARY FRIDAY, JUNE 8, 2018 6-10PM NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD New York City Chapter Honoring the 2018 Champions of Justice Honorees at Previous NLG/NYC Chapter Dinners: 1974 The Founders of the Guild (first 2006 Frank Big Black Smith and Elizabeth Chapter Dinner Journal) Fink 1975 Dorothy Shtob 2007 70th Anniversary – Honoring Past 1976 Marshall Perlin Presidents of the New York City Chapter 1977 Arthur Kinoy 2008 Margaret Ratner Kunstler, Mary Kaufman, William Schaap, Sarah 1978 Victor Rabinowitz Kunstler, and Gideon Orion Oliver 1979 Martin Popper 2009 Daniel L. Alterman, Ann Fawcett 1980 John Abt Ambia, Susan Barrie, Arlene F. Boop, 1981 Ralph Shapiro Susan M. Cohen, Timothy L. Collins, Stephen Dobkin, Harvey Epstein, Polly 1982 Catherine Roraback, Eustis, Hillary Exter, Robyn D. Fisher, Rhonda Copelon, Judith Levin, Nancy James B. Fishman, William J. Gribben, Stearns Amy Hammersmith, Kenneth B. 1983 David Scribner Hawco, Samuel J. Himmelstein, Janet 1984 Haywood Burns Ray Kalson, Kent Karlsson, Robert A. Katz, Stuart W. Lawrence, Bill Leavitt, 1985 William Kunstler Jon Lilienthal, Seth A. Miller, Roberto 1986 The Guild’s 5 Decades of Work in Morrero, Martin S. Needelman, Paul Human Rights, Peace & Justice, with Peloquin, Deborah Rand, Jessica Rose, special award to Nelson Mandela Ollie Rosengart, Kenneth Schaeffer, 1987 50th Anniversary – Celebrating Our Andrew Scherer, Mary E. Sheridan, Past, Building the Future Heidi Siegfried, Barbara Small, Gibb Surette, Susan D. Susman, Richard 1988 Bonnie Brower J. Wagner, Marti Weithman, Special 1989 Morton Stavis Recognition Robert Boyle 1990 The Guild’s Support of the Labor 2010 Myron Beldock, James I. Meyerson, Movement, 1937-1990 Lynne Stewart, Evelyn W.