Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ladainian TOMLINSON

THE NEW LA STADIUM THE CHARGERS ARE BRINGING THE FIGHT TO INGLEWOOD. The new LA Stadium at Hollywood Park, home of your Los Angeles Chargers in 2020, will deliver a revolutionary football experience custom-designed for the LA fan. The new Los Angeles Stadium at Hollywood Park will have the first ever, completely covered, open-air stadium with a clear view of the sky. The campus will feature 25 acres of park providing rare and expansive open space in the center of LA. The 70,000-seat stadium will be the center of a vibrant mixed-use development, just 3 miles from LAX. The low-profile building will sit 100 feet below ground level. The video board will provide a 360-degree double-sided 4K digital display viewing experience. There will be several clubs within the stadium, all offering LA-inspired premium dining and private entrances. Many concourse and club spaces will have patios bathed in sunlight. Champions Plaza will host pregame activities and special events, and feature a 6,000-seat performance venue. Entry and exit will be easy, and there will be more than 10,500 parking spaces on site. For more information on becoming a 2020 LA Stadium Season Ticket Member, visit FightforLA.com II OWNERSHIP, COACHING AND ADMINISTRATION 20182018 THE NEW LA STADIUM CHARGERSSCHEDULESCHEDULEGOGO BOLTSBOLTS PRESEASON WEEK DATE OPPONENT TIME NETWORK THE CHARGERS ARE 1 Sat. Aug. 11 @ Cardinals 7:00 pm KABC BRINGING THE FIGHT 2 Sat. Aug. 18 SEAHAWKS 7:00 pm KABC 3 Sat. Aug. 25 SAINTS 5:00 pm CBS * TO INGLEWOOD. -

Earl Morrall Flyer

Proceeds benefit Drug Free Collier, uniting the community to protect the children of Collier County from substance abuse. April 18-19, 2021 The Earl Morrall Celebrity Pairing Dinner and Golf Classic invite you to join our 17th annual Celebrity Golf Event on April 18-19, 2021 benefitting Drug Free Collier. On Sunday, April 18th, The Hilton Naples puts Kim Bokamper with 1972 Miami Dolphin's Perfect your foursome & guest's shoulder to shoulder with Season Team "Locker Room Moments" former NFL Players including the 1972 Perfect Season Miami Dolphins! Football greats from Bob Griese, Larry Csonka, Mercury Morris, Charlie Babb, Dick Anderson, Larry Little, Larry Ball, and other Hall Of Famers mingle at the pre-dinner cocktail reception followed by a fabulous dinner, live auction, and an extraordinary presentation on Sunday night. Mercury Morris Charlie Babb On Monday, April 19th, at The Club at The Strand Golf Course, each foursome will be captained by an NFL Alumni or sports celebrity. Space is limited, and you don't want to miss this tournament. Get your friends together & build your foursome or just sign up as a solo player and we'll pair you with the perfect team. Don't wait, slots are filling up quickly! Sponsorship Opportunities are available! o-day event. Larry Csonka Mercury Morris Bob Griese Proceeds benefit Drug Free Collier, uniting the community to protect the children of Collier County from substance abuse. Learn more and register Earlmorrallcelebritygolf.com April 18-19, 2021 2021 Golf & Sponsor Registration Form Your Name _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

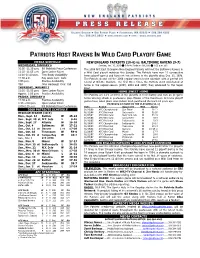

Patriots Host Ravens in Wild Card Playoff Game

PATRIOTS HOST RAVENS IN WILD CARD PLAYOFF GAME MEDIA SCHEDULE NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (10-6) vs. BALTIMORE RAVENS (9-7) WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 6 Sunday, Jan. 10, 2010 ¹ Gillette Stadium (68,756) ¹ 1:00 p.m. EDT 10:50 -11:10 a.m. Bill Belichick Press Conference The 2009 AFC East Champion New England Patriots will host the Baltimore Ravens in 11:10 -11:55 a.m. Open Locker Room a Wild Card playoff matchup this Sunday. The Patriots have won 11 consecutive 11:10-11:20 p.m. Tom Brady Availability home playoff games and have not lost at home in the playoffs since Dec. 31, 1978. 11:30 a.m. Ray Lewis Conf. Calls The Patriots closed out the 2009 regular-season home schedule with a perfect 8-0 1:05 p.m. Practice Availability record at Gillette Stadium. The first three times the Patriots went undefeated at TBA John Harbaugh Conf. Call home in the regular-season (2003, 2004 and 2007) they advanced to the Super THURSDAY, JANUARY 7 Bowl. 11:10 -11:55 p.m. Open Locker Room HOME SWEET HOME Approx. 1:00 p.m. Practice Availability The Patriots are 11-1 at home in the playoffs in their history and own an 11-game FRIDAY, JANUARY 8 home winning streak in postseason play. Eleven of the franchise’s 12 home playoff 11:30 a.m. Practice Availability games have taken place since Robert Kraft purchased the team 16 years ago. 1:15 -2:00 p.m. Open Locker Room PATRIOTS AT HOME IN THE PLAYOFFS (11-1) 2:00-2:15 p.m. -

The Following Players Comprise the College Football Great Teams 2 Card Set

COLLEGE FOOTBALL GREAT TEAMS OF THE PAST 2 SET ROSTER The following players comprise the College Football Great Teams 2 Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. Players in bold are starters. If there is a difference between the player's card and the roster sheet, always use the card information. The number in ()s after the player name is the number of cards that the player has in this set. See below for a more detailed explanation of new symbols on the cards. 1971 NEBRASKA 1971 NEBRASKA 1972 USC 1972 USC OFFENSE DEFENSE OFFENSE DEFENSE EB: Woody Cox End: John Adkins EB: Lynn Swann TA End: James Sims Johnny Rodgers (2) TA TB, OA Willie Harper Edesel Garrison Dale Mitchell Frosty Anderson Steve Manstedt John McKay Ed Powell Glen Garson TC John Hyland Dave Boulware (2) PA, KB, KOB Tackle: John Grant Tackle: Carl Johnson Tackle: Bill Janssen Chris Chaney Jeff Winans Daryl White Larry Jacobson Tackle: Steve Riley John Skiles Marvin Crenshaw John Dutton Pete Adams Glenn Byrd Al Austin LB: Jim Branch Cliff Culbreath LB: Richard Wood Guard: Keith Wortman Rich Glover Guard: Mike Ryan Monte Doris Dick Rupert Bob Terrio Allan Graf Charles Anthony Mike Beran Bruce Hauge Allan Gallaher Glen Henderson Bruce Weber Monte Johnson Booker Brown George Follett Center: Doug Dumler Pat Morell Don Morrison Ray Rodriguez John Kinsel John Peterson Mike McGirr Jim Stone ET: Jerry List CB: Jim Anderson TC Center: Dave Brown Tom Bohlinger Brent Longwell PC Joe Blahak Marty Patton CB: Charles Hinton TB. -

Big 12 Conference Schools Raise Nine-Year NFL Draft Totals to 277 Alumni Through 2003

Big 12 Conference Schools Raise Nine-Year NFL Draft Totals to 277 Alumni Through 2003 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Apr. 26, 2003 DALLAS—Big 12 Conference teams had 10 of the first 62 selections in the 35th annual NFL “common” draft (67th overall) Saturday and added a total of 13 for the opening day. The first-day tallies in the 2003 NFL draft brought the number Big 12 standouts taken from 1995-03 to 277. Over 90 Big 12 alumni signed free agent contracts after the 2000-02 drafts, and three of the first 13 standouts (six total in the first round) in the 2003 draft were Kansas State CB Terence Newman (fifth draftee), Oklahoma State DE Kevin Williams (ninth) Texas A&M DT Ty Warren (13th). Last year three Big 12 standouts were selected in the top eight choices (four of the initial 21), and the 2000 draft included three alumni from this conference in the first 20. Colorado, Nebraska and Florida State paced all schools nationally in the 1995-97 era with 21 NFL draft choices apiece. Eleven Big 12 schools also had at least one youngster chosen in the eight-round draft during 1998. Over the last six (1998-03) NFL postings, there were 73 Big 12 Conference selections among the Top 100. There were 217 Big 12 schools’ grid representatives on 2002 NFL opening day rosters from all 12 members after 297 standouts from league members in ’02 entered NFL training camps—both all-time highs for the league. Nebraska (35 alumni) was third among all Division I-A schools in 2002 opening day roster men in the highest professional football configuration while Texas A&M (30) was among the Top Six in total NFL alumni last autumn. -

2020 NFL Draft Scouting Report: QB Joe Burrow, LSU

2020 NFL DRAFT SCOUTING REPORT JANUARY 15, 2020 2020 NFL Draft Scouting Report: QB Joe Burrow, LSU *Our QB grades can and will change as more information comes in from Pro Day workouts, leaked Wonderlic test results, etc. We will update ratings as new info becomes available. Is there anyone speaking out against Joe Burrow as a top QB prospect? Does anyone even doubt that he’s the #1 pick in the draft (not necessarily admitting he’s the best player, just that he will be the #1 pick)? So, what more could I add to the Burrow lovefest of 2020? If I say that I’m very much a Burrow fan for the next level, pro-Burrow as a scout – well then there’s some intrigue taken out of this report already. Just another guy singing Burrow’s praises, big deal! However, despite any desire I might have to surprise you with a controversial take on Burrow, I’m just not finding any reason for a controversial, contrarian call for him as a bust. Not at all. The only real intrigue remaining with Burrow, for scouts and fans – just how good is Joe Burrow? As I was researching background for this report, I was watching some media segments and commentary, post-National Title game. One that caught my eye/ear was Colin Cowherd trying to classify/comp Burrow. He had top CFB analyst Joel Klatt on his show, and Klatt, in full seriousness, compared Burrow to Joe Montana… which makes some sense the more you think of it. The following day, on his show, Cowherd compared Burrow to Tony Romo…a quarterback Colin holds in high regard, so it was a nice comp, even if not quite as glowing as Klatt’s Montana call. -

Miami Dolphins Weekly Release

Miami Dolphins Weekly Release Game 12: Miami Dolphins (4-7) vs. Baltimore Ravens (4-7) Sunday, Dec. 6 • 1 p.m. ET • Sun Life Stadium • Miami Gardens, Fla. RESHAD JONES Tackle total leads all NFL defensive backs and is fourth among all NFL 20 / S 98 defensive players 2 Tied for first in NFL with two interceptions returned for touchdowns Consecutive games with an interception for a touchdown, 2 the only player in team history Only player in the NFL to have at least two interceptions returned 2 for a touchdown and at least two sacks 3 Interceptions, tied for fifth among safeties 7 Passes defensed, tied for sixth-most among NFL safeties JARVIS LANDRY One of two players in NFL to have gained at least 100 yards on rushing (107), 100 receiving (816), kickoff returns (255) and punt returns (252) 14 / WR Catch percentage, fourth-highest among receivers with at least 70 71.7 receptions over the last two years Of two receivers in the NFL to have a special teams touchdown (1 punt return 1 for a touchdown), rushing touchdown (1 rushing touchdown) and a receiving touchdown (4 receiving touchdowns) in 2015 Only player in NFL with a rushing attempt, reception, kickoff return, 1 punt return, a pass completion and a two point conversion in 2015 NDAMUKONG SUH 4 Passes defensed, tied for first among NFL defensive tackles 93 / DT Third-highest rated NFL pass rush interior defensive lineman 91.8 by Pro Football Focus Fourth-highest rated overall NFL interior defensive lineman 92.3 by Pro Football Focus 4 Sacks, tied for sixth among NFL defensive tackles 10 Stuffs, is the most among NFL defensive tackles 4 Pro Bowl selections following the 2010, 2012, 2013 and 2014 seasons TABLE OF CONTENTS GAME INFORMATION 4-5 2015 MIAMI DOLPHINS SEASON SCHEDULE 6-7 MIAMI DOLPHINS 50TH SEASON ALL-TIME TEAM 8-9 2015 NFL RANKINGS 10 2015 DOLPHINS LEADERS AND STATISTICS 11 WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN 2015/WHAT TO LOOK FOR AGAINST THE RAVENS 12 DOLPHINS-RAVENS OFFENSIVE/DEFENSIVE COMPARISON 13 DOLPHINS PLAYERS VS. -

Wild Card Playoffs

Wild Card Playoffs 3 WILD CARD PLAYOFFS AFC WILD CARD PLAYOFF GAMES Season Date Winner (Share) Loser (Share) Score Site Attendance 2005 Jan. 8 Pittsburgh ($17,000) Cincinnati ($19,000) 31-17 Cincinnati 65,870 Jan. 7 New England ($19,000) Jacksonville ($17,000) 28-3 Foxborough 68,756 2004 Jan. 9 Indianapolis ($18,000) Denver ($15,000) 49-24 Indianapolis 56,609 Jan. 8 N.Y. Jets ($15,000) San Diego ($18,000) 20-17* San Diego 67,536 2003 Jan. 4 Indianapolis ($18,000) Denver ($15,000) 41-10 Indianapolis 56,586 Jan. 3 Tennessee ($15,000) Baltimore ($18,000) 20-17 Baltimore 69,452 2002 Jan. 5 Pittsburgh ($17,000) Cleveland ($12,500) 36-33 Pittsburgh 62,595 Jan. 4 N.Y. Jets ($17,000) Indianapolis ($12,500) 41-0 East Rutherford 78,524 2001 Jan. 13 Baltimore ($12,500) Miami ($12,500) 20-3 Miami 72,251 Jan. 12 Oakland ($17,000) N.Y. Jets ($12,500) 38-24 Oakland 61,503 2000 Dec. 31 Baltimore (12,500) Denver ($12,500) 21-3 Baltimore 69,638 Dec. 30 Miami ($16,000) Indianapolis ($12,500) 23-17* Miami 73,193 1999 Jan. 9 Miami ($10,000) Seattle ($16,000) 20-17 Seattle 66,170 Jan. 8 Tennessee ($10,000) Buffalo (10,000) 22-16 Nashville 66,672 1998 Jan. 3 Jacksonville ($15,000) New England ($10,000) 25-10 Jacksonville 71,139 Jan. 2 Miami ($10,000) Buffalo ($10,000) 24-17 Miami 72,698 1997 Dec. 28 New England ($15,000) Miami ($10,000) 17-3 Foxborough 60,041 Dec. -

Helmet-To-Helmet Contact:Avoiding a Lifetime Penalty by Creating a Duty to Scan Active Nfl Players for Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy

Journal of Legal Medicine, 34:425–452 Copyright C 2013 American College of Legal Medicine 0194-7648 print / 1521-057X online DOI: 10.1080/01947648.2013.859969 HELMET-TO-HELMET CONTACT:AVOIDING A LIFETIME PENALTY BY CREATING A DUTY TO SCAN ACTIVE NFL PLAYERS FOR CHRONIC TRAUMATIC ENCEPHALOPATHY Thomas A. Drysdale* [T]his stuff is for real because I’m experiencing it now. I’m scared to death. I have four kids, I have a beautiful wife and I’m scared to death what might happen to me 10 or 15 years from now. Rodney Harrison1 INTRODUCTION On May 2, 2012, Junior Seau, one of the most talented and feared linebackers ever to play in the National Football League (NFL), died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the chest.2 Seau was only 43 years old and left behind three teenaged children.3 Less than a year later, in January of 2013, Seau’s family sued the NFL after tissue samples from Seau’s donated4 brain showed that he was suffering from chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), “a degenerative brain disease linked to repeated head hits and brain trauma.”5 The Seau family * Third-year law student at Southern Illinois University. Address correspondence to Mr. Drysdale at Southern Illinois University School of Law, Law Journal Office, Lesar Law Building, Carbondale, Illinois 62901 or via e-mail at [email protected]. 1 Kevin Kaduk, Rodney Harrison Says He’s “Scared to Death” After a Career Filled with Concussions,YAHOO!SPORTS, Jan. 30, 2013, http://sports.yahoo.com/blogs/nfl-shutdown-corner/ rodney-harrison-says-scared-death-career-filled-concussions-015416631-nfl.html. -

Home Away April 23, at 5 P.M

the 2020 nfl draft 2020 opponents The 85th National Football League Draft will begin on Thursday, home away April 23, at 5 p.m. PT. It will serve as three-day virtual fundraiser Atlanta Falcons Buffalo Bills befitting charities that are battling the spread of COVID-19. Carolina Panthers Cincinnati Bengals Denver Broncos Denver Broncos The Los Angeles Chargers enter the 2020 NFL Draft with seven Jacksonville Jaguars Kansas City Chiefs selections — one in each round. The team is slated to kick off its Kansas City Chiefs Las Vegas Raiders selections at No. 6. Las Vegas Raiders Miami Dolphins New England Patriots New Orleans Saints The 2020 NFL Draft will mark General Manager Tom Telesco's New York Jets Tampa Bay Buccaneers eighth with the team. Since joining the team in 2013, Telesco has drafted five players that eventually made a Pro Bowl with the team, including three who did so multiple times. Wide receiver quick facts of the draft Keenan Allen, who was the team's third-round selection in Schedule: DAY DATE START TIME ROUNDS Telesco's inaugural draft with the Bolts, has been to three-straight 1 Thursday, April 23 5 p.m. PT 1 Pro Bowls. Safety Derwin James Jr., and defensive back Desmond 2 Friday, April 24 4 p.m. PT 2-3 King II are the two players Telesco has drafted to earn first-team 3 Saturday, April 25 9 a.m. PT 4-7 All-Pro recognition from The Associated Press. Television: NFL Network, ESPN and ABC will televise the draft Teams have 10 minutes to select and player in the first round and on all three days. -

HUSKIES Heritage the Apple Cup Dogs and Cats

Heritage HUSKIES Heritage The Apple Cup Dogs and cats. Could there be a more natural rivalry? Huskies and Cougars. The annual Washington-Washington State matchup is definitely one of the best rivalries in college football today. Up for grabs each year is the Apple Cup, a trophy sponsored by the Washington State Apple Commission and presented by the state’s governor. The series dates back to 1900 when the teams played to a 5-5 tie in Seattle, but only since 1962 has the winner been awarded the Apple Cup. Washington holds a 61-27-6 record in the 94-game series, and is 29-11 in Apple Cup games. Like most rivalries, each game is a new chapter with unpredictable results, regardless of records, mo- mentum or history. It is a game based more on emotion and determination than scouting reports and talent. Though the schools are on opposite sides of the state, creating a geographic split among fans, the annual meeting splits the state in other ways — some- times between members of the same family. Such was the case in 1990 when Husky freshman Travis Hanson waged a personal kicking battle with his brother Jason, the Cougars’ All-American kicker. But while individual stories give the Apple Cup its The Apple Cup trophy is awarded annually to the winner of the game between Washington and character, its enormity and magnitude come from the Washington State. The Huskies lead the series 29-11 since it became known as the Apple Cup. number of times the game has determined Rose Bowl fate for either team. -

Swimming (4-0) Players in Double Figures

2C SPORTS t Wisconsin State Journal, Thursday, July 29,1993 Today Friday Saturday Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday BREWERS North men take gold Boston New York NMVork MHImor* Bittlmor* B*)Umor» NwVort »:30p.m. 1 p.m. 8:30 p.m. 13:30 p.m. 12:30 pjnl 8:Mp.m. 6:30 p.m. Ch.47 Ch.47 Rodriguez HUSKIES As Bradley signs, Burlington Rockford Rockford K*n» Kan» Rockford Rockford 76ers clean house 7p.m. 6p.m. 7p.m. County County >< breaks cheek SAN ANTONIO (AP) — The The Philadelphia 76ers signed | | Home games | | Roadjames North men and South women came Shawn Bradley Wednesday for a away with basketball gold at the large, but undisclosed, amount, U.S. Olympic Festival. Alex Rodri- then — to make room for him SPORTS ON THE AIR guez came away with a broken and his salary — dumped the rest cheek. of the players on the National TELEVISION Noon — Pro tennis — Early-round 7 p.m. — Pro baseball — Atlanta Rodriguez, baseball's No. 1 draft Basketball Association team. matches of the Canadian Open, at at Houston; WTBS. choice, was struck by a ball while Pretty much. Montreal; ESPN. 8 p.m. — Pro boxing — James in the dugout Wednesday before his It went like this: Bradley, 6:30 p.m. — Pro bowling — Finals Toney vs. Daniel Garcia, In super mid- South team's game against the signed. Manute Bol, gone. Charles of PBA Senior Showboat Invitational, dleweight bout at West Orange, N.J.; at Las Vegas; ESPN. ESPN. North. Shackleford, gone. Ron Anderson, "This injury will have no effect gone.