Phase 1 Heritage Impact Assessment Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Profile: City of Ekurhuleni

2 PROFILE: CITY OF EKURHULENI PROFILE: CITY OF EKURHULENI 3 CONTENT 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................................... 5 2. Introduction: Brief Overview............................................................................. 6 2.1 Historical Perspective ............................................................................................... 6 2.1 Location ................................................................................................................... 7 2.2. Spatial Integration ................................................................................................. 8 3. Social Development Profile............................................................................... 9 3.1 Key Social Demographics ........................................................................................ 9 3.2 Health Profile .......................................................................................................... 12 3.3 COVID-19 .............................................................................................................. 13 3.4 Poverty Dimensions ............................................................................................... 15 3.4.1 Distribution .......................................................................................................... 15 3.4.2 Inequality ............................................................................................................. 16 3.4.3 Employment/Unemployment -

For More Information, Contact the Office of the Hod: • 011 999 3845/6194 Introduction

The City of Ekurhuleni covers an extensive area in the eastern region of Gauteng. This extensive area is home to approximately 3.1 million and is a busy hub that features the OR Tambo International Airport, supported by thriving business and industrial activities. Towns that make up the City of Ekurhuleni are Greater Alberton, Benoni, Germiston, Duduza, Daveyton, Nigel, Springs, KwaThema, Katlehong, Etwatwa, Kempton Park, Edenvale, Brakpan, Vosloorun, Tembisa, Tsakane, and Boksburg. Ekurhuleni region accounts for a quarter of Gauteng’s economy and includes sectors such as manufacturing, mining, light and heavy industry and a range of others businesses. Covering such a large and disparate area, transport is of paramount importance within Ekurhuleni, in order to connect residents to the business areas as well as the rest of Gauteng and the country as a whole. Ekurhuleni is highly regarded as one of the main transport hubs in South Africa as it is home to OR Tambo International Airport; South Africa’s largest railway hub and the Municipality is supported by an extensive network of freeways and highways. In it features parts of the Maputo Corridor Development and direct rail, road and air links which connect Ekurhuleni to Durban; Cape Town and the rest of South Africa. There are also linkages to the City Deep Container terminal; the Gautrain and the OR Tambo International Airport Industrial Development Zone (IDZ). For more information, contact the Office of the HoD: • 011 999 3845/6194 Introduction The City of Ekurhuleni covers an extensive area in the eastern region of Gauteng. This extensive area is home to approximately 3.1 million and is a busy hub that features the OR Tambo International Airport, supported by thriving business and industrial activities. -

Spatial Planning Directorate December 2012

CITY PLANNING DEPARTMENT – SPATIAL PLANNING DIRECTORATE DECEMBER 2012 1 REGIONAL SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK REGION A EKURHULENI METROPOLITAN MUNICIPALITY SPATIAL CONCEPT December 2012 Commissioned by Drafted by Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality Metroplan Town and Regional Planners 2 TABLE OF CONTENT 4.2 Open Space Network ............................................................... 14 5 NODAL STRUCTURE .......................................................................... 17 5.1 MSDF Proposals .......................................................................... 17 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 1 5.1.1 Primary Nodes ................................................................... 17 1.1 Aim and Objectives ...................................................................... 1 5.1.2 Secondary Nodes .............................................................. 18 1.2 The Study Area ............................................................................. 2 5.1.3 Station Nodes ..................................................................... 21 1.3 Structure of the Document ........................................................... 2 5.1.4 Combined MSDF Nodes ................................................... 22 2 PROJECT BACKGROUND ................................................................... 4 5.2 Proposed Nodes ......................................................................... 22 3 MAIN FINDINGS OF THE STATUS QUO ANALYSIS -

June 2021 Ekurhuleni Load Shedding Schedules

June 2021 Ekurhuleni Load Shedding Schedules DAY OF THE MONTH Start End Stage 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 1 1 13 9 5 2 14 10 6 3 15 11 7 4 16 12 8 5 1 13 9 6 2 14 10 7 3 15 11 8 4 16 2 2 5 1 13 9 6 2 14 10 7 3 15 11 8 4 16 12 9 5 1 13 10 6 2 14 11 7 3 15 12 8 4 3 3 9 5 1 13 10 6 2 14 11 7 3 15 12 8 4 16 13 9 5 1 14 10 6 2 15 11 7 3 16 12 8 4 4 13 9 5 1 14 10 6 2 15 11 7 3 16 12 8 4 1 13 9 5 2 14 10 6 3 15 11 7 4 16 12 5 5 11 12 8 4 16 13 9 5 1 14 10 6 2 15 11 7 3 16 12 8 4 1 13 9 5 2 14 10 6 3 15 6 6 15 16 12 8 4 1 13 9 5 2 14 10 6 3 15 11 7 4 16 12 8 5 1 13 9 6 2 14 10 7 3 7 7 3 4 16 12 8 5 1 13 9 6 2 14 10 7 3 15 11 8 4 16 12 9 5 1 13 10 6 2 14 11 7 00:00 03:00 8 8 7 8 4 16 12 9 5 1 13 10 6 2 14 11 7 3 15 12 8 4 16 13 9 5 1 14 10 6 2 15 11 1 2 14 10 6 3 15 11 7 4 16 12 8 5 1 13 9 6 2 14 10 7 3 15 11 8 4 16 12 9 5 1 2 2 6 2 14 10 7 3 15 11 8 4 16 12 9 5 1 13 10 6 2 14 11 7 3 15 12 8 4 16 13 9 5 3 3 10 6 2 14 11 7 3 15 12 8 4 16 13 9 5 1 14 10 6 2 15 11 7 3 16 12 8 4 1 13 9 4 4 14 10 6 2 15 11 7 3 16 12 8 4 1 13 9 5 2 14 10 6 3 15 11 7 4 16 12 8 5 1 13 5 5 1 13 9 5 2 14 10 6 3 15 11 7 4 16 12 8 5 1 13 9 6 2 14 10 7 3 15 11 8 4 16 6 6 5 1 13 9 6 2 14 10 7 3 15 11 8 4 16 12 9 5 1 13 10 6 2 14 11 7 3 15 12 8 4 7 7 9 5 1 13 10 6 2 14 11 7 3 15 12 8 4 16 13 9 5 1 14 10 6 2 15 11 7 3 16 12 8 02:00 05:00 8 8 13 9 5 1 14 10 6 2 15 11 7 3 16 12 8 4 1 13 9 5 2 14 10 6 3 15 11 7 4 16 12 1 3 15 11 7 4 16 12 8 5 1 13 9 6 2 14 10 7 3 15 11 8 4 16 12 9 5 1 13 10 6 2 2 2 7 3 15 11 8 4 16 12 9 5 -

EPISCOPAL CHURCHPEOPLE for a I=REE SOUTHERN AFRICA ·E 339 Lafayette Street, New York, N.Y

EPISCOPAL CHURCHPEOPLE for a i=REE SOUTHERN AFRICA ·E 339 Lafayette Street, New York, N.Y. 10012·2725 C (212) 4n-0066 S A #50 10 December 1986 CHILDREN UNDER REPRESSION These horrifying facts about the Pretoria regime's treatment of black South African young people have been exhaustively researched and just published un- , der the auspices of the Detainees' Parents Support Committee by a group-of ' people and organizations who have been active in the monitoring, care and treatment of detainees and their families. This document - 220 pages long - examines the pOlitical context of repress ion, the complex web of laws under which black people in South Africa must suffer, including the vast powers of the security apparatus, citizenship laws which dispossess people, and the powers of banning; the central role of South Africa's inferior schooling system in igniting black youths' resistance to' the entire apartheid structure;and the damage to the children by the brutality and repression to which they are subjected. Human rights groups in South Africa have underway a campaign to draw urgent', attention to children in detention. ,Pretoria has had to respond to 'domestic,'" and growing world concern - by trying to downplay the issue. Arid by attack;;, "::, ing those pressing the campaign . Officials of the Black Sashano the DPSC,,:, have just been given banning orders,~ notably Ms Audrey Coleman of the DPSC who has devoted years of work for young people in detention. ' , Your' help is needed to help the children of South Africa. Attached hereto is a partial list of young detainees. Choose a name (or names') and write urging their immediate release, to: President P. -

Understanding Our People a Journey Through Census

UNDERSTANDING OUR PEOPLE: A JOURNEY THROUGH CENSUS 2011 IN GAUTENG Acknowledgements : PRESENTATION BY Dr Ros Hirschowitz RENDANI MABILA AND Sharthi Laldaparsad MARCUS SEEPE Table of content 1. Introduction 2. Geographic Information 3. Demographic Information 4. Migration 5. Education 6. Labour Market 7. Income Status 8. Summary 9. References Introduction Ekurhuleni meaning “place of peace” in Xitsonga is a metropolitan municipality situated at the east part of Gauteng x and share boarders with City of Johannesburg ,Sedibeng, City of Tshwane and Nkangala (Mpumalanga ) The metro covers an area of about 2 000km2 and is highly urbanized with a population density of 1 609 people per km2. City of Ekurhuleni is divided into six planning regions namely: v Region A:Germiston v Region B:Thembisa v Region C:Daveyton v Region D:Benoni v Region E:Boksburg v Region F:Katlehong/Thokoza Region A: Germiston Germiston is a city in the East Rand of Gauteng it is also the location of Rand Airport and home to the South African Airways Museum Region B: Thembisa Tembisa is a large township situated to the north of Kempton Park on the East Rand, It was established in 1957 when Africans were resettled from Alexandra and other areas in Edenvale, Kempton Park, Midrand and Germiston. Region C: Daveyton Daveyton is a township that borders Etwatwa to the north, springs to the east, Benoni to the south, and Boksburg to the West. The nearest town is Benoni, which is 18 kilometres away. Daveyton is one of the largest townships with many population in South Africa, together with Etwatwa,Herry Gwala and Cloverdene.It was established in 1952 when 151,656 people were moved from Benoni, the old location of Etwatwa. -

GERMISTON ACUPUNCTURE Limpopo

GERMISTON ACUPUNCTURE Limpopo Tembisa Cullinan Sentrarand Pretoria Bronkhorstspruit Kempton Park Daveyton Edenvale Sandton Krugersdorp Kempton Park N12 Delmas Randfontein Benoni Johannesburg Bedfordview Soweto Ekurhuleni Boksburg Devon Germiston Brakpan Westonaria N17 Springs Heidelberg Alberton Vereeniging Kwa-Thema Vanderbijlpark Balfour EKURHULENI REGIONAL POSITION REGIONAL EKURHULENI Thokoza Vosloorus Tsakane Katlehong Sasolburg Deneysville Tambo Springs Duduza Nigel EKURHULENI AT A GLANCE PROPOSED PROJECT • The construction of the theatre within Germiston urban precinct acts as a catalyst for the performing arts with Ekurhuleni region • The project will convert the historic Germiston Carnegie Library into contemporary theatre • A place of regional economic importance and performance • A Gateway into Ekurhuleni & greater Germiston • A place for reinforcing community interaction PROPOSED PROJECT STRATEGY Growth Development • To promote tourism • To Re-invent Germiston to its former glory Strategy • To promote social cohesion • To enhance property value 10 Point Plan • To revive city liveability Municipal Spatial • To support artists in Ekurhuleni • Development To promote job creation Framework • To preserve and promote the cities cultural heritage, architecture and urban design Precinct • To upgrade and renew public infrastructure Plan Theatre CBD – Seven Germiston Precincts SPATIAL TRANSFORMATION AND INCLUSION • To support the Ekurhuleni core node being created in the Germiston CBD • The theatre site link to the Germiston Station Precinct -

The Ramaphosa Case Study

THE RAMAPHOSA CASE STUDY ‘Many shades of the truth’: THE RAMAPHOSA CASE STUDY by Nobayethi Dube 1 ‘Many shades of the truth’: THE RAMAPHOSA CASE STUDY by Nobayethi Dube Part I: Executive summary .............................................................1 Part II: Introduction .........................................................................3 Terms of Reference ...............................................................................................................................4 Methodology ..........................................................................................................................................5 Structure of this report ........................................................................................................................6 Overview ..................................................................................................................................................7 Part III: Versions of truth .................................................................7 The affected ..........................................................................................................................................13 Community organising .....................................................................................................................18 Social cohesion ...................................................................................................................................18 Cross-cutting issues ............................................................................................................................19 -

Daveyton Sub District of Ekurhuleni South East Magisterial District

# # !C # # # # # ^ !C # !.!C # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C ^ # # # # # ^ # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # !C # # # # # # # !C ^ # # # # # # # # ^ # # # !C # # # # # # # !C # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # !C # !C # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # !C # # ^ # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # ^ # # !C # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # !C # # # # # !C# # # # # # #!C # # # # !C # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # ^ # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # !C # # # # !C # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # !C # # # !C # # ## # # !C # # # !C # # !C !. # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # ^ # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C !C # ## # # # # # # !C # # # !C # # # # # # # !C # !C # # # ^ # # # !C # # # # # # ^ # # !C # # !C # !C # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # !C## # # # # -

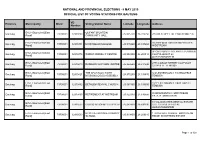

8 May 2019 Official List of Voting Stations for Gauteng

NATIONAL AND PROVINCIAL ELECTIONS - 8 MAY 2019 OFFICIAL LIST OF VOTING STATIONS FOR GAUTENG VD Province Municipality Ward Voting Station Name Latitude Longitude Address Number EKU - Ekurhuleni [East OLIFANTSFONTEIN Gauteng 79700001 32910230 -25.955770 28.228750 PEARS STREET OLIFANTSFONTEIN Rand] COMMUNITY HALL EKU - Ekurhuleni [East 01 ASHFORD MISTREAM ESTATES Gauteng 79700001 32910331 MIDSTREAM COLLEGE -25.915860 28.197260 Rand] MIDSTREAM 00 CNR PORCELAIN AND ALLUMINIUM EKU - Ekurhuleni [East Gauteng 79700001 32910375 WORLD WORSHIP CENTRE -25.950850 28.204810 CLAYVILLE EXT 29 Rand] OLIFANTSFONTEIN EKU - Ekurhuleni [East 2773 COBALT STREET CLAYVILLE Gauteng 79700001 32910410 RAINBOW DAYCARE CENTRE -25.952660 28.211240 Rand] CLAYVILLE TEMBISA EKU - Ekurhuleni [East THE APOSTOLIC FAITH 5005 EXTENSION 8 TSWELOPELE Gauteng 79700001 32910421 -25.970280 28.198870 Rand] MISSION LOGOS ASSEMBLY TEMBISA EKU - Ekurhuleni [East 1617 EXTENSION 8 TSWELOPELE Gauteng 79700001 32910432 BETHLEM REVIVAL CHURCH -25.967860 28.199650 Rand] TEMBISA EKU - Ekurhuleni [East 00 BRAKFONTEIN MIDSTREAM Gauteng 79700001 32910465 RETIREMENT AT MISTREAM -25.922340 28.190800 Rand] ESTATE MIDSTREAM 01 VALUMAX RESIDENTIAL ESTATE EKU - Ekurhuleni [East Gauteng 79700001 32910522 CURRO ACADEMY CLAYVILLE -25.982810 28.190030 CLA CLAYVILLE EXT 45 Rand] OLIFANTSFONTEIN EKU - Ekurhuleni [East MIDSTREAM RIDGE PRIMARY 1 RIDGEWAY AVENUE MIDSTREAM Gauteng 79700001 32910533 -25.919450 28.209610 Rand] SCHOOL RIDGE MIDSTREAM ESTATE Page 1 of 308 NATIONAL AND PROVINCIAL ELECTIONS - 8 MAY 2019 OFFICIAL LIST OF VOTING STATIONS FOR GAUTENG VD Province Municipality Ward Voting Station Name Latitude Longitude Address Number EKU - Ekurhuleni [East TENT (WINNIE MANDELA 4237 RAMAPHOSA STREET WINNIE Gauteng 79700002 32890080 -25.984690 28.213880 Rand] ZONE 11 GROUNDS) MANDELA SECTION TEMBISA. -

REZONING Erf 31023 DAVEYTON DAVEYTON CLINIC PROJECT

MOTIVATIONAL MEMORANDUM: REZONING Erf 31023 DAVEYTON DAVEYTON CLINIC PROJECT Ground Floor | Henley House | Tel: +27 11 888 8685 Greenacres Office Park Fax: +27 86 641 7769 13 Victory Road | Victory Park | 2195 Email: [email protected] P.O. Box 52287 | Saxonwold | 2132 Web: www.kipd.co.za MOTIVATIONAL MEMORANDUM: REZONING OF ERF 31023 DAVEYTON DAVEYTON CLINIC PROJECT FOR ON BEHALF OF Revision 2.0 (September 2016) Compiled by : Title Position Date K. Modise Town Planner 24 August 2016 Reviewed by : Title Position Date S. Cole Town Planner 24 August 2016 FILE : D/16/A/1002 Rezoning- Daveyton Clinic PAGE 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SUMMARY OF APPLICATION ................................................................................................................................. 4 2. GENERAL INFORMATION ....................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1. Locality ................................................................................................................................................................. 5 2.2. The Site ................................................................................................................................................................. 6 3. LEGAL DETAILS ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 3.1. Ownership ............................................................................................................................................................ -

HWSETA Accredited and Approved Sdps for Full Qualifications As at 24

Accredited Provider Name AccreditationStartDate AccreditationEndDate SAQA ID Title of Qualification ProviderPhone PhysicalAddressLine1 PhysicalAddressLine2 PhysicalAddressLine3 Province 4 Degree Consulting 27-Jan-17 31-Mar-20 74269 (LP 74290) NC: Occupational Health Safety and (011) 064 1620 140 Kelvin Drive Morningside Johannesburg Gauteng Environment 79806 (LP 50062) NC: Occupational Hygiene and Safety AAA Phoenix Health and Safety 29-Jun-16 31-Mar-20 74269 (LP 74290) NC: Occupational Health, Safety and (012 ) 654 8111 4 Castile Villa, 130 Mopani Road Hemnus Park Centurion Gauteng Training and Consulting Environment 79806 (LP 50062) NC: Occupational Health & Safety Aba Health 22-Mar-17 31-Mar-20 49057 FETC : Theology and Ministry (012) 567 5502 918 Berg Avenue Nina Park Pretoria Gauteng 49256 FETC: Counselling Arbinet Training and Development 24-Oct-17 31-Mar-20 74269 (LP 74290) NC:Occupational Health ,Safety and (043) 722 8003 35 Empire Avenue Cambridge Eastern Cape Environment 79806 (LP 50062) NC:Occupational Hygiene and Safety Eastern Cape Abraham Kriel Maria Kloopers 16-Sep-15 31-Mar-20 60209 FETC: Child and Youth Care Work (011) 839 3058 Cnr of Marais Street and Kamp Street Langlagte Gauteng Kinderhuis Absolute Central College 30-Mar-17 25-Jan-20 49606 GETC:Ancillary Health Care 267 Proes Street Pretoria Gauteng Absolute Health Services 11-Oct-17 31-Mar-20 74269 (LP 74290) NC:Occupational Health ,Safety and (010) 592 2111 2 Selbourne Road Johannersburg North Johannesburg Gauteng Environment Abafundi Institute of Health and 23-May-14