The Fatalis Project: a Creative Response To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Star Channels, Jan. 13-19

JANUARY 13 - 19, 2019 staradvertiser.com END OF DAYS Federal agent Brad Wolgast (Mark-Paul Gosselaar) and the most important girl in the world (Saniyya Sidney) are on the run in an epic tale of survival in a world on the brink of total destruction. The end is near when an experiment with a deadly virus goes off the rails in The Passage. Premiering Monday, Jan. 14, on Fox. WEEKLY NEWS UPDATE LIVE @ THE LEGISLATURE Join Senate and House leadership as they discuss upcoming legislation and issues of importance to the community. TOMORROW, 8:30AM | CHANNEL 49 | olelo.org/49 olelo.org ON THE COVER | THE PASSAGE Most wanted A fugitive pair run for their incredibly high and that things might get a bit Horror Story: Roanoke”) is deemed to be the lives in ‘The Passage’ apocalyptic. perfect candidate and is selected to be a test Like all good tales of science gone bad, the subject. Project Noah scientists, comprised of lead Federal agent Brad Wolgast (Mark-Paul By Francis Babin scientist Dr. Major Nichole Sykes (Caroline Gosselaar, “Franklin & Bash”) is chosen to TV Media Chikezie, “The Shannara Chronicles”), Dr. Jonas protect the young girl and escort her to the re- Lear (Henry Ian Cusick, “The 100”) and other mote facility, but things soon get complicated he new year is officially upon us, which geniuses are in desperate need of human test when the two form a very close bond. Over the means New Year’s resolutions are in full subjects. course of their trip to the secret medical facil- vogue once again. -

Voltron Comic Download Torrent Comic Books

voltron comic download torrent Comic books. Comic books in the Voltron franchise are pieces of fiction that extend the multiple canons. Over the three decades since the debut of Voltron: Defender of the Universe in 1984 there have been multiple publishers that would produce their own separate series for the franchise. Among them were continuations of TV series (with the exception of Voltron: The Third Dimension) that would run alongside the airing of its respective series. Other publishers would produce their own universe separate from any canon established by a TV series or would be loosely based off of it as a reboot. Contents. Japanese continuities. Terebi Land (1981 - 1984) Page from Terebi Land's March 1981 chapter of the Hyakujūō Golion manga. Terebi Land (also known as Television Land or TV Land) was a Japanese children's television magazine that focused on various anime and tokusatsu. In it were interviews, artwork, and individual manga chapters of TV series that were airing at the time. Terebi Land would publish many of Toei's super robot franchises including Beast King GoLion, Armored Fleet DaiRugger XV, and Lightspeed Electroid Albegas. Tsuchiyama Yoshiki, of Cyborg 009 fame, would be the illustrator for Beast King GoLion's manga, whereas Tsuhara Yoshiaki would illustrate the latter two. Like the tie-in comics for series as recent as Voltron: Legendary Defender, these manga chapters would run alongside its respective anime series as it airs. However, they would have different plots while using the same characters. For instance, Shirogane dies in both incarnations but would he would die under different circumstances in both versions. -

Queer Utopia in Steven Universe Mandy Elizabeth Moore University of Florida, [email protected]

Research on Diversity in Youth Literature Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 5 June 2019 Future Visions: Queer Utopia in Steven Universe Mandy Elizabeth Moore University of Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://sophia.stkate.edu/rdyl Recommended Citation Moore, Mandy Elizabeth (2019) "Future Visions: Queer Utopia in Steven Universe," Research on Diversity in Youth Literature: Vol. 2 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. Available at: http://sophia.stkate.edu/rdyl/vol2/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SOPHIA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research on Diversity in Youth Literature by an authorized editor of SOPHIA. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moore: Future Visions: Queer Utopia in Steven Universe Since it premiered on Cartoon Network in 2013, Steven Universe has garnered both praise and criticism for its portrayal of queer characters and its flexible approach to gender. Created by Rebecca Sugar, a bisexual and nonbinary artist, the show tells the story of Steven, a half-human, half-alien teenager raised by a trio of alien parental figures called the Crystal Gems. Steven’s adventures range from helping his friends at the local donut shop to defending Earth from the colonizing forces of the Gem Homeworld. Across its five seasons, this series has celebrated many queer firsts for animated children’s content. In 2018, Steven Universe aired one of the first cartoon same-sex wedding scenes (“Reunited”), and in 2019, it became the first animated show to win a Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) award, taking home the prize for Outstanding Kids and Family Programming. -

The Rhetorics of the Voltron: Legendary Defender Fandom

"FANS ARE GOING TO SEE IT ANY WAY THEY WANT": THE RHETORICS OF THE VOLTRON: LEGENDARY DEFENDER FANDOM Renee Ann Drouin A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2021 Committee: Lee Nickoson, Advisor Salim A Elwazani Graduate Faculty Representative Neil Baird Montana Miller © 2021 Renee Ann Drouin All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Lee Nickoson, Advisor The following dissertation explores the rhetorics of a contentious online fan community, the Voltron: Legendary Defender fandom. The fandom is known for its diversity, as most in the fandom were either queer and/or female. Primarily, however, the fandom was infamous for a subsection of fans, antis, who performed online harassment, including blackmailing, stalking, sending death threats and child porn to other fans, and abusing the cast and crew. Their motivation was primarily shipping, the act of wanting two characters to enter a romantic relationship. Those who opposed their chosen ship were targets of harassment, despite their shared identity markers of female and/or queer. Inspired by ethnographically and autoethnography informed methods, I performed a survey of the Voltron: Legendary Defender fandom about their experiences with harassment and their feelings over the show’s universally panned conclusion. In implementing my research, I prioritized only using data given to me, a form of ethical consideration on how to best represent the trauma of others. Unfortunately, in performing this research, I became a target of harassment and altered my research trajectory. In response, I collected the various threats against me and used them to analyze online fandom harassment and the motivations of antis. -

? Download Free Voltron: Defender of The

Register Free To Download Files | File Name : Voltron: Defender Of The Universe, Vol. Ii Issue 9; Sept. 2004 PDF VOLTRON: DEFENDER OF THE UNIVERSE, VOL. II ISSUE 9; SEPT. 2004 Comic January 1, 2004 Author : Did You Check eBay? Fill Your Cart With Color Today!","adext":{"sitelinks":{"l":[],"tid":""},"tid":"1"},"ae":null,"c":"https://duckduckgo.com/y.js?ad_pro vider=bingv7aa&eddgt=lh5HGrMrELRYGz7Ixo81ww%3D%3D&rut=90035036a569acfd4d9530e7a 3a2c68fe52d553c84408fc996e0ebdc30859aae&u3=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.bing.com%2Faclick %3Fld%3De8ODmrwqtfbkPDJaJKkZEU_TVUCUwLvWPwAkQEFpp81DEAbXhaEMwjtFfSPbiLJd CDugMJkfxd7QeJrdE5GuES_YH8oDl9hqG_KaShAgPd8J2YBZ6PkYj1XDOiePQAwiKFBxOjkCt8 UZlahCL0WzL_%2D1FHa0uGOzQ3vnH0iP_%2Dsp0WMGNZK0RE28knSnSEGxypd4631g%26u %3DaHR0cCUzYSUyZiUyZnd3dy5lYmF5LmNvbSUyZnVsayUyZnNjaCUyZiUzZl9ua3clM2R2b2x0 cm9uJTI2bm9yb3ZlciUzZDElMjZta2V2dCUzZDElMjZta3JpZCUzZDcxMS0zNDAwMC0xMzA3OC0 wJTI2bWtjaWQlM2QyJTI2a2V5d29yZCUzZHZvbHRyb24lMjZjcmxwJTNkXyUyNk1UX0lEJTNkJTI 2Z2VvX2lkJTNkJTI2cmxzYXRhcmdldCUzZGt3ZC03NjY5MTA3MTAyNzgwMiUzYWxvYy0xNTYlM jZhZHBvcyUzZCUyNmRldmljZSUzZGMlMjZta3R5cGUlM2QlMjZsb2MlM2QxNTYlMjZwb2klM2QlM jZhYmNJZCUzZCUyNmNtcGduJTNkMzI5ODU0Njk0JTI2c2l0ZWxuayUzZCUyNmFkZ3JvdXBpZC UzZDEyMjcwNTUxMjg2NTM1MDYlMjZuZXR3b3JrJTNkcyUyNm1hdGNodHlwZSUzZHAlMjZtc2N sa2lkJTNkNjhiZWNlNGU2ZjcwMTM5MWViODhhZTk1YTIyZTUzYjU%26rlid%3D68bece4e6f7013 91eb88ae95a22e53b5&vqd=3-276754780307400450561506926103426315680- 149382371238630188221044527126906250971&iurl=%7B1%7DIG%3DFF9851BF5D9F4411A9 A8759113D75E75%26CID%3D2FC3FC7AA3E36EE126E9EC1CA2486F72%26ID%3DDevEx%2 C5649.1","d":"ebay.com","h":0,"i":"","k":0,"m":0,"o":"","p":1,"relevancy":{"abstract":"Did%20You%20 -

Canal Institucional *Hq Co | Canal Trece *Hd Co

CO | CABLE NOTICIAS *HD CL | CANAL 13 *FHD | Directo AR | AMERICA TV *HD | op2 AR | SENADO *HD CO | CANAL CAPITAL *HD CL | CANAL 13 CABLE *HD AR | C5N *HD AR | TELEFE *FHD CO | CANAL INSTITUCIONAL *HQ CL | CANAL 13 AR | C5N *HD | op2 AR | TELEFE *HD CO | CANAL TRECE *HD INTERNACIONACIONAL *HD AR | CANAL 21 *HD AR | TELEFE *HD CO | CANAL UNO *HD CL | CHV *HQ AR | CANAL 26 *HD AR | TELEMAX *HD CO | CANTINAZO *HD CL | CHV *HD AR | CANAL 26 NOTICIAS *HD AR | TELESUR *HD CO | CARACOL *HQ CL | CHV *FHD AR | CANAL 26 NOTICIAS *HD AR | TN *HD CO | CARACOL *HD CL | CHV *FHD | Directo AR | CANAL DE LA CIUDAD *HD AR | TV PUBLICA *FHD CO | CARACOL *FHD CL | LA RED *HQ AR | CANAL DE LA MUSICA AR | TV PUBLICA *HD CO | CARACOL 2 *FHD CL | LA RED *HD *HD AR | CINE AR *HD AR | AR | TV PUBLICA *HD | op2 CO | CARACOL INTERNACIONAL *HD CL | LA RED *FHD CINE AR *HD AR | TV5 *HD CO | CITY TV *HD CL | LA RED *FHD | Directo AR | CIUDAD MAGAZINE *HD AR | TVE *HD CO | COSMOVISION *HD CL | MEGA *HQ AR | CN23 *HD AR | VOLVER *HD CO | EL TIEMPO *HD CL | MEGA *HD AR | CN23 *HD AR | TELEFE INTERNACIONAL CO | LA KALLE *HD CL | MEGA *FHD AR | CONEXION *HD *HD A&E *FHD CO | NTN24 *HD CL | MEGA *HD | Op2 AR | CONSTRUIR *HD A3 SERIES *FHD CO | RCN *HQ CL | MEGA *FHD | Directo AR | CRONICA *HD AMC *FHD CO | RCN *HD CL | MEGA PLUS *FHD AR | CRONICA *HD ANTENA 3 *FHD CO | RCN *FHD CL | TVN *HQ AR | DEPORTV *HD AXN *FHD CO | RCN 2 *FHD CL | TVN *HD AR | EL NUEVE *HD CINECANAL *FHD CO | RCN NOVELAS *HD CL | TVN *FHD AR | EL NUEVE *FHD CINEMAX *FHD CO | RCN INTERNACIONAL CL | -

Voltron Script Script

VOLTRON By Chris Harris 549 North Laburnum Ave. Apt.3 Richmond, VA 23223 Cell: 252/258-0978 [email protected] FADE IN: INT. OBSERVATORY - DAY Doctor LARRY MOSLEY is standing at a refreshment table at the far wall pouring himself a cup of coffee. SUPER: CALIFORNIA Three BEEPS come from a computer behind him. Larry drops the cup to the floor and runs over to the monitor. Larry picks up the phone. LARRY Come in here fast. You won’t believe this. Larry hangs the phone up. He continues to stare at the monitor. A SCIENTIST walks up and looks over Larry’s shoulder. The BEEPS increase in frequency. There are readings on the monitor. SCIENTIST What is it? LARRY Contact. All these years we've been sending signals up and finally we were responded to. INT. APARTMENT BEDROOM - DAY ROCK MUSIC is being played from another room. SUPER: ARIZONA KEITH KOGANE, 28, sits up in the bed. He smiles, shakes his head and gets up. Keith goes into the bathroom. 2. KITCHEN Keith walks in. The music is turned off but the television is on in the living-room. Keith opens the refrigerator and looks inside. Keith speaks without turning around. KEITH Did you save me anything to eat? LIVING ROOM HUNK GARETT, 27, belches. HUNK I’m not that greedy. KITCHEN KEITH Who told you that? Keith pulls out a cartoon of milk and closes the refrigerator. He reaches into the cabinet and pulls down a box of cereal. Keith fixes a bowl of cereal and sits down at the kitchen bar. -

Network Totals

Network Totals Total CBS 66 SYNDICATED 66 Netflix 51 Amazon 49 NBC 35 ABC 33 PBS 29 HBO 12 Disney Channel 12 Nickelodeon 12 Disney Junior 9 Food Network 9 Verizon go90 9 Universal Kids 6 Univision 6 YouTube RED 6 CNN en Español 5 DisneyXD 5 YouTube.com 5 OWN 4 Facebook Watch 3 Nat Geo Kids 3 A&E 2 Broadway HD 2 conversationsinla.com 2 Curious World 2 DIY Network 2 Ora TV 2 POP TV 2 venicetheseries.com 2 VICELAND 2 VME TV 2 Cartoon Network 1 Comcast Watchable 1 E! Entertainment 1 FOX 1 Fuse 1 Google Spotlight Stories/YouTube.com 1 Great Big Story 1 Hallmark Channel 1 Hulu 1 ION Television 1 Logo TV 1 manifest99.com 1 MTV 1 Multi-Platform Digital Distribution 1 Oculus Rift, Samsung Gear VR, Google Daydream, HTC Vive, Sony 1 PSVR sesamestreetincommunities.org 1 Telemundo 1 UMC 1 Program Totals Total General Hospital 26 Days of Our Lives 25 The Young and the Restless 25 The Bold and the Beautiful 18 The Bay The Series 15 Sesame Street 13 The Ellen DeGeneres Show 11 Odd Squad 8 Eastsiders 6 Free Rein 6 Harry 6 The Talk 6 Zac & Mia 6 A StoryBots Christmas 5 Annedroids 5 All Hail King Julien: Exiled 4 An American Girl Story - Ivy & Julie 1976: A Happy Balance 4 El Gordo y la Flaca 4 Family Feud 4 Jeopardy! 4 Live with Kelly and Ryan 4 Super Soul Sunday 4 The Price Is Right 4 The Stinky & Dirty Show 4 The View 4 A Chef's Life 3 All Hail King Julien 3 Cop and a Half: New Recruit 3 Dino Dana 3 Elena of Avalor 3 If You Give A Mouse A Cookie 3 Julie's Greenroom 3 Let's Make a Deal 3 Mind of A Chef 3 Pickler and Ben 3 Project Mc² 3 Relationship Status 3 Roman Atwood's Day Dreams 3 Steve Harvey 3 Tangled: The Series 3 The Real 3 Trollhunters 3 Tumble Leaf 3 1st Look 2 Ask This Old House 2 Beat Bugs: All Together Now 2 Blaze and the Monster Machines 2 Buddy Thunderstruck 2 Conversations in L.A. -

La Guía Del Paladín

dâctilos Javier Barrera La guía del Paladín EL DEFENSOR LEGENDARIO Cartoné 150 x 222 mm Aprende todo lo que necesitas para ser un paladín VOLTRON 155 x 228 mm de Voltron con esta increíble guía. Lee todas las curiosidades acerca de Voltron, conoce el Castillo de los Leones, descubre la verdad que se esconde 15 mm detrás de la Misión Cerbero… ¡y averigua qué león pilotarías si fueses un defensor del universo! 4 0 La guía del Paladín LA GUÍA DEL PALADÍN PVP 11,95 € 10239132 UVI brillo en zonas (VER PDF “UVI”, están en color magenta www.planetadelibrosinfantilyjuvenil.com 100%). DreamWorks Voltron Legendary Defender © 2019 DreamWorks Animation LLC. TM World Events Productions LLC. All Rights reserved. 26 de Abril de 2019 10239132_La_guia_del_paladin.indd 1 26/4/19 11:32 LA GUÍA DEL PALADÍN T_10239132_La_guia_del_paladin.indd 1 26/4/19 11:38 DreamWorks Voltron Legendary Defender © 2019 DreamWorks Animation LLC. TM World Events Productions LLC. All rights reserved. Publicado en España por Editorial Planeta, S. A., 2019 Avda. Diagonal, 662-664, 08034 Barcelona (España) www.planetadelibrosinfantilyjuvenil.com www.planetadelibros.com Primera edición: junio de 2019 ISBN: 978-84-08-21061-0 Depósito legal: B. 9.558-2019 Impreso en España El papel utilizado para la impresión de este libro está calificado como papel ecológico y procede de bosques gestionados de manera sostenible. No se permite la reproducción total o parcial de este libro, ni su incorporación a un sistema informático, ni su transmisión en cualquier forma o por cualquier medio, sea este electrónico, mecánico, por fotocopia, por grabación u otros métodos, sin el permiso previo y por escrito del editor. -

EL ORIGEN DE VOLTRON Javier Barrera

dâctilos EL ORIGEN DE VOLTRON Javier Barrera El origen de Voltron Rústica con solapas Cinco pilotos adolescentes 140 x 205 mm de la Tierra han descubierto 142 x 205 mm EL DEFENSOR LEGENDARIO en mitad del desierto el León Azul, un robot gigante. Ninguno de ellos sabe que están a punto de embarcarse VOLTRON en una aventura intergaláctica. 4 ¿Serán capaces de dejar a 0 un lado sus diferencias y de aprender a formar a Voltron, la única esperanza para derrotar el malvado imperio Galra? El destino del universo está en juego... www.planetadelibrosinfantilyjuvenil.com El origen de Voltron PVP 9,95 € 10239129 Adaptado por CALA SPINNER Y NATALIE SHAW UVI brillo en zonas (VER PDF DreamWorks Voltron Legendary Defender © 2019 “UVI”, están en color magenta DreamWorks Animation LLC. TM World Events Productions LLC. All rights reserved. 100%). 26 de Marzo 2019 10239129_El_origen_de_Voltron.indd 1 25/4/19 17:00 El origen de Voltron Adaptado por Cala Spinner y Natalie Shaw T_10239129_El_origen_de_Voltron.indd 1 25/4/19 17:05 DreamWorks Voltron Legendary Defender © 2019 DreamWorks Animation LLC. TM World Events Productions LLC. All rights reserved. Publicado en España por Editorial Planeta, S. A., 2019 Avda. Diagonal, 662-664, 08034 Barcelona (España) www.planetadelibrosinfantilyjuvenil.com www.planetadelibros.com Primera edición: junio de 2019 ISBN: 978-84-08-21059-7 Depósito legal: B. 9.557-2019 Impreso en España El papel utilizado para la impresión de este libro está calificado como papel ecológico y procede de bosques gestionados de manera sostenible. No se permite la reproducción total o parcial de este libro, ni su incorporación a un sistema informático, ni su transmisión en cualquier forma o por cualquier medio, sea este electrónico, mecánico, por fotocopia, por graba- ción u otros métodos, sin el permiso previo y por escrito del editor. -

Microservice-Powered Applications It Worked for Voltron, It Can Work for You!

Microservice-Powered Applications It worked for Voltron, it can work for you! Bryan Soltis – Kentico Technical Evangelist Voltron? • Originally aired in 1984 (all others don’t count) • Based on Planet Arus (Castle of Lions) • Originally a great robot split into 5 lions by Witch Haggar • Black Lion (Lightning) – Keith • Red Lion (Magma) - Lance • Blue Lion (Water) – Sven / Princess Allura • Green Lion (Wind) - Pidge • Yellow Lion (Sand) – Hunk • Enemies • Witch Haggar • Emperor Zeppo • Prince Lotor • Robeasts! What are micro services? • Small, independent processes • Communicate using language-agnostic APIs • Decoupled building blocks for larger applications • Remove single points of failure • Best of breed services • Allow for unique integrations/capabilities Identify the bad guys • Complex, restrictive content management • Technology lock-in • Inflexible, non-scalable platforms • Ineffective, static search • Complex integrations, processes • Boring, static user experience How are companies using them? • Integrating systems • Microsoft Azure • Amazon AWS • Scalable platforms • Netflix • Uber • Remove technology monoliths • Groupon • Serve multiple services • Amazon • Deploy changes easier • Ebay Assembling my team • Kentico Cloud – SaaS Content Repository • Azure App Services – Web Hosting • Azure Search – SaaS Search • Azure Functions – Kentico Cloud / Search Integration / Alexa • Azure Bot Service – Interactive FAQs • Application Insights – Performance reporting Let’s see it in action PROS CONS • Functionality isolation • Information -

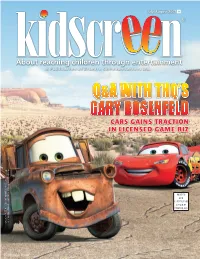

Q&A with Thq's Gary Rosenfeld

US$7.95 in the U.S. CA$8.95 in Canada US$9.95 outside of CanadaJuly/August & the U.S. 2007 1 ® Q&A WITH THQ’S GARY ROSENFELD CCARSARS GGAINSAINS TTRACTIONRACTION IINN LLICENSEDICENSED GGAMEAME BBIZIZ NUMBER 40050265 40050265 NUMBER ANADA USPS Approved Polywrap ANADA AFSM 100 CANADA POST AGREEMENT POST CANADA C IN PRINTED 001editcover_July_Aug07.indd1editcover_July_Aug07.indd 1 77/19/07/19/07 77:00:43:00:43 PMPM KKS.4562.Cartoon.inddS.4562.Cartoon.indd 2 77/20/07/20/07 55:06:05:06:05 PMPM KKS.4562.Cartoon.inddS.4562.Cartoon.indd 3 77/20/07/20/07 55:06:54:06:54 PMPM #8#+.#$.'019 9 9 Animation © Domo Production Committee. Domo © NHK-TYO 1998. [ZVijg^c\I]ZHiVg<^gah Star Girls and Planet Groove © Dianne Regan Sean Regan. XXXCJHUFOUUW K<C<M@J@FEJ8C<J19`^K\ek<ek\ikX`ed\ek%K\c%1)()$-'+$''-+\ok%)'(2\dX`c1iZfcc`ej7Y`^k\ek%km C@:<EJ@E>GIFDFK@FEJ19`^K\ek<ek\ikX`ed\ek%K\c%1)()$-'+$''-+\ok%)'-2\dX`c1idXippXe\b7Y`^k\ek%km KKS4548.BIGS4548.BIG TTENT.inddENT.indd 2 77/19/07/19/07 66:54:45:54:45 PMPM 1111 F3 to mine MMOG space for TV concepts 114Parthenon4 Kids: Geared up and ready to invest 1177 Will Backseat TV boost Nick’s in-car profile? 225Storm Hawks5 goes jjuly/augustuly/august viral with Guerilla 0077 HHighlightsighlights ffromrom tthishis iissuessue 10 up front 24 marketing France TV to invest in Chrysler and Nick hope more content and global to get more mileage out Special Reports web presence of the minivan set with 29 RADARSCREEN backseat TV feature Fred Seibert’s Frederator Films 13 ppd tries a fresh approach to Parthenon Kids offers 26 digital