The Ascent of Rondoy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Introduction to the Bofedales of the Peruvian High Andes

An introduction to the bofedales of the Peruvian High Andes M.S. Maldonado Fonkén International Mire Conservation Group, Lima, Peru _______________________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY In Peru, the term “bofedales” is used to describe areas of wetland vegetation that may have underlying peat layers. These areas are a key resource for traditional land management at high altitude. Because they retain water in the upper basins of the cordillera, they are important sources of water and forage for domesticated livestock as well as biodiversity hotspots. This article is based on more than six years’ work on bofedales in several regions of Peru. The concept of bofedal is introduced, the typical plant communities are identified and the associated wild mammals, birds and amphibians are described. Also, the most recent studies of peat and carbon storage in bofedales are reviewed. Traditional land use since prehispanic times has involved the management of water and livestock, both of which are essential for maintenance of these ecosystems. The status of bofedales in Peruvian legislation and their representation in natural protected areas and Ramsar sites is outlined. Finally, the main threats to their conservation (overgrazing, peat extraction, mining and development of infrastructure) are identified. KEY WORDS: cushion bog, high-altitude peat; land management; Peru; tropical peatland; wetland _______________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION organic soil or peat and a year-round green appearance which contrasts with the yellow of the The Tropical Andes Cordillera has a complex drier land that surrounds them. This contrast is geography and varied climatic conditions, which especially striking in the xerophytic puna. Bofedales support an enormous heterogeneity of ecosystems are also called “oconales” in several parts of the and high biodiversity (Sagástegui et al. -

Landsat TM and ETM+ Derived Snowline Altitudes in the Cordillera Huayhuash and Cordillera Raura, Peru, 1986–2005

The Cryosphere, 5, 419–430, 2011 www.the-cryosphere.net/5/419/2011/ The Cryosphere doi:10.5194/tc-5-419-2011 © Author(s) 2011. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Landsat TM and ETM+ derived snowline altitudes in the Cordillera Huayhuash and Cordillera Raura, Peru, 1986–2005 E. M. McFadden1,*,**, J. Ramage1, and D. T. Rodbell2 1Earth and Environmental Sciences, Lehigh University, 1 West Packer Ave., Bethlehem, PA 18015, USA 2Geology Department, Union College, Schenectady, NY 12308, USA *now at: Byrd Polar Research Center, The Ohio State University, 1090 Carmack Road, Columbus, OH 43210, USA **now at: School of Earth Sciences, The Ohio State University, 275 Mendenhall Laboratory, 125 S. Oval Mall, Columbus, OH 43210, USA Received: 13 August 2010 – Published in The Cryosphere Discuss.: 6 October 2010 Revised: 10 March 2011 – Accepted: 4 May 2011 – Published: 23 May 2011 Abstract. The Cordilleras Huayhuash and Raura are remote and better-known Cordillera Blanca, and has 117 glaciers glacierized ranges in the Andes Mountains of Peru. A robust covering ∼85 km2 (Morales Arnao, 2001). Peaks are typ- assessment of modern glacier change is important for under- ically over 6000 m a.s.l., with the highest peak recorded at standing how regional change affects Andean communities, 6617 m a.s.l. (Nevado Yerupaja).´ The Cordillera Raura, lo- and for placing paleo-glaciers in a context relative to mod- cated to the southeast of the Cordillera Huayhuash, has ern glaciation and climate. Snowline altitudes (SLAs) de- a slightly smaller (55 km2) glacier area (Morales Arnao, rived from satellite imagery are used as a proxy for modern 2001). -

Folleto Inglés (1.995Mb)

Impressive trails Trekking in Áncash Trekking trails in Santa Cruz © J. Vallejo / PROMPERÚ Trekking trails in Áncash Áncash Capital: Huaraz Temperature Max.: 27 ºC Min.: 7 ºC Highest elevation Max.: 3090 meters Three ideal trekking trails: 1. HUAYHUASH MOUNTAIN RANGE RESERVED AREA Circuit: The Huayhuash Mountain Range 2. HUASCARÁN NATIONAL PARK SOUTH AND HUARAZ Circuit: Olleros-Chavín Circuit: Day treks from Huaraz Circuit: Quillcayhuanca-Cójup 3. HUASCARÁN NATIONAL PARK NORTH Circuit: Llanganuco-Santa Cruz Circuit: Los Cedros-Alpamayo HUAYHUASH MOUNTAIN RANGE RESERVED AREA Circuit: Huayhuash Mountain Range (2-12 days) 45 km from Chiquián to Llámac to the start of the trek (1 hr. 45 min. by car). This trail is regarded one of the most spectacular in the world. It is very popular among mountaineering enthusiasts, since six of its many summits exceed 6000 meters in elevation. Mount Yerupajá (6634 meters) is one such example: it is the country’s second highest peak. Several trails which vary in length between 45 and 180 kilometers are available, with hiking times from as few as two days to as many as twelve. The options include: • Circle the mountain range: (Llámac-Pocpa-Queropalca Quishuarcancha-Túpac Amaru-Uramaza-Huayllapa-Pacllón): 180 km (10-12 days). • Llámac-Jahuacocha: 28 km (2-3 days). Most hikers begin in Llámac or Matacancha. Diverse landscapes of singular beauty are clearly visible along the treks: dozens of rivers; a great variety of flora and fauna; turquoise colored lagoons, such as Jahuacocha, Mitucocha, Carhuacocha, and Viconga, and; the spectacular snow caps of Rondoy (5870 m), Jirishanca (6094 m), Siulá (6344 m), and Diablo Mudo (5223 m). -

Mapping the Cordillera Huayhuash Digital Alpine Cartography with Imperfect Data

Mapping the Cordillera Huayhuash Digital Alpine Cartography with Imperfect Data Martin Gamache Digital Cartographer Alpine Mapping Guild 1 Kenney St #2, Jamaica Plain, MA 02130 USA [email protected] www.alpinemapguild.com This paper will examine the issues involved in creating a topographic map for an audience of recreationists (climbers, trekkers, and hikers) for a remote mountain area of Peru. The Cordillera Huayhuash, a sub range of the Cordillera Occidental of the Peruvian Andes, is a compact but impressive massif located a few kilometers south of the better known Cordillera Blanca. Like its sister range it was initially surveyed and mapped in the 30’s by an Österreichischen Alpenverein (Alpenvereinskarte/ D.O.A.V.) party. Since then the range has been remapped by the Peruvian I.G.N. at 1:100,000 scale. The two map sheets covering the range while useful do not meet the requirements of climbers and hikers. Unlike the D.O.A.V. sheets (Cordillera Blanca North and South) covering the Cordillera Blanca which are in the process of being updated and reissued, it may be years before the Cordillera Huayhuash sheet is revised by the prestigious European group. Other recreational maps also fail to meet the needs of this special group of users. In the fall of 1999 the Alpine Mapping Guild obtained digital topographic data to the Cordillera Huayhuash and has been preparing a shaded relief topographic map of the range. Initial quality control verification work was done in the field during the 2000 climbing season by the AMG. A first edition of the map is planned for release in late spring of 2002.This paper reviews previously available maps to the areas and how the AMG map improves upon this work to serve its audience’s special needs. -

A Survey of Andean Ascents 1961-1970

ML A Survey of Andean Ascents 1961-1970 A Survey of Andean Ascents: 1961~1970 Part I. Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru. EVELIO ECHEVARR~A -,!!.-N the years 1962 and 1963, the American A/pine Journal published “A survey of Andean ascents”. It included climbs dating back to the activity deployed by the Andean In- dians in the early 1400’s to the year 1960 inclusive. This present survey attempts to continue the former by covering all traceable Andean ascents that took place from 1961 to 1970 inclusive. Hopefully the rest of the ascents (in Bolivia, Chile and Argentina) will be published in 1974. The writer feels indebted to several mountaineers who readily pro- vided invaluable help: the editor of this journal, Mr. H. Adams Carter, who suggested and directed this project: Messrs. John Ricker (Canada), Olaf Hartmann (Germany) and Mario Fantin (Italy), who all gave advice on several ranges, particularly in Peru. Besides, the following persons also provided important information that helped to solve a good many problems on the history and geography of Andean peaks: Messrs. D.F.O. Dangar and T.S. Blakeney (Great Britain), Ben Curry (Great Britain-Colombia), Ichiro Yoshizawa (Japan), Hans-Dieter Greul and Christian Jahl (Germany), J. Monroe Thorington, Stanley Shepard and John Peyton (United States) and Christopher Jones (Great Britain- United States). The American Alpine Club, through its secretary, Miss Margot McKee, helped immensely by loaning books and journals. To all these persons I express my gratitude. This survey has been compiled mostly from mountaineering and scientific literature, as well as from correspondence and conversation with mountaineers. -

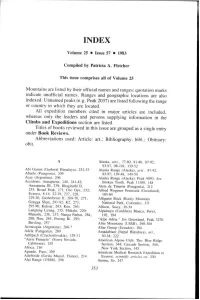

Mountains Are Listed by Their Official Names and Ranges; Quotation Marks Indicate Unofficial Names

INDEX Volume 25 0 Issue 57 0 1983 Compiled by Patricia A. Fletcher This issue comprises al1 of Volume 25 Mountains are listed by their official names and ranges; quotation marks indicate unofficial names. Ranges and geographic locations are also indexed. Unnamed peaks (e.g. Peak 2037) are listed following the range or country in which they are located. All expedition members cited in major articles are included, whereas only the leaders and persons supplying information iti the Climbs and Expeditions section are listed. Titles of books reviewed in this issue are grouped as a single entry under Book Reviews. Abbreviations used: Article: art.; Bibliography: bibl.; Obituary: obit. A Alaska, arts., 77-80, 81-86, 87-92, 93-97, 98-101; 139-52 Abi Gamin (Garbwal Himalaya), 252-53 Alaska Range (Alaska), arts.. 87-92, Abuelo (Patagonia), 209 93-97; 139-48, 149-50 Acay (Argentina), 206 Alaska Range (Alaska): Peak 9050. See Accidents: Annapuma, 240, 241-42; Broken Tooth. Peak 11300, 148 Annapuma III, 239; Bhagirathi II, Aleta de Tiburbn (Patagonia), 212 253; Broad Peak, 271; Cho Oyu, 232; Alfred Wegener Peninsula (Greenland), Everest, 8-14. 22-29, 227, 228, 183-84 229-30; Gasherbrum II, 269-70, 271; Alligator Rock (Rocky Mountain Gongga Shari,, 291-92; K2, 273, National Park, Colorado), 171 295-96; Kuksar, 283; Kun, 265; Allison, Stacy, 30-34 Langtang Lirung, 235; Makalu, 220; Alpamayo (Cordillera Blanca, Peru), Manaslu, 236, 237; Nanga Parbat, 284, 192, 194 288; Nun, 263. Porong Ri, 295; “Alpe Adria.” See Greenland, Peak 3270. Shivling, 257 Altai Mountains (USSR), 298-300 Aconcagua (Argentina), 206-7 Altar Group (Ecuador), 184 Adela (Patagoma), 209 Amadablam (Nepal Himalaya), an., AdrSpach (Czechoslovakia), 129-3 1 30-34; 222 “Aene Pinnacle” (Sierra Nevada, American Alpine Club, The: Blue Ridge California), 155 Section. -

Copyright by Jennifer Kristen Lipton 2008

Copyright by Jennifer Kristen Lipton 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Jennifer Kristen Lipton Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Human Dimensions of Conservation, Land Use, and Climate Change in Huascaran National Park, Peru Committee: Kenneth R. Young, Supervisor Gregory W. Knapp Kelley A. Crews Karl W. Butzer Richard H. Richardson Human Dimensions of Conservation, Land Use, and Climate Change in Huascaran National Park, Peru by Jennifer Kristen Lipton, B.S.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Dedication This is dedicated to the following list because of one or all of these characteristics: inspiration, beauty, integrity, patience, and support The mountain landscape, water in all forms, the flora and fauna of the Peruvian Andes The communities, families, and friends that live in and around the Cordillera Blanca My mentors that guided me in the discipline, in the classroom, and in the field Friends that I’ve had all along and friends that I met along the way Loving family that were always by my side Thank you Acknowledgements There is not enough space, and certainly not enough time, to express the amount of gratitude that I have to so many for making this research a reality. Many of the people that deserve this acknowledgement will probably not ever read these pages. And, so it is those individuals that I want to acknowledge first: the inhabitants living within reach of the Cordillera Blanca that sat with me, laughed with me, patiently listened while I spoke in broken Spanish, answered my questions, let me sit in on meetings, taught me about their landscape and lives, taught me how to dance a huayno , and showed me a dynamic landscape that is worth more than all of the gold contained within the hills. -

Geological Society of America Bulletin

Downloaded from gsabulletin.gsapubs.org on May 4, 2011 Geological Society of America Bulletin Structural Evolution of the Cordillera Huayhuash, Andes of Peru PETER J CONEY Geological Society of America Bulletin 1971;82;1863-1884 doi: 10.1130/0016-7606(1971)82[1863:SEOTCH]2.0.CO;2 Email alerting services click www.gsapubs.org/cgi/alerts to receive free e-mail alerts when new articles cite this article Subscribe click www.gsapubs.org/subscriptions/ to subscribe to Geological Society of America Bulletin Permission request click http://www.geosociety.org/pubs/copyrt.htm#gsa to contact GSA Copyright not claimed on content prepared wholly by U.S. government employees within scope of their employment. Individual scientists are hereby granted permission, without fees or further requests to GSA, to use a single figure, a single table, and/or a brief paragraph of text in subsequent works and to make unlimited copies of items in GSA's journals for noncommercial use in classrooms to further education and science. This file may not be posted to any Web site, but authors may post the abstracts only of their articles on their own or their organization's Web site providing the posting includes a reference to the article's full citation. GSA provides this and other forums for the presentation of diverse opinions and positions by scientists worldwide, regardless of their race, citizenship, gender, religion, or political viewpoint. Opinions presented in this publication do not reflect official positions of the Society. Notes Copyright © 1971, The Geological Society of America, Inc. Copyright is not claimed on any material prepared by U.S. -

Trekking Gear List & General Info 2019

Superior Personal Tours in the Peruvian Andes Specialists in: Trekking, Climbing, Camping, Tours & Adventure Perú Head Office: New Zealand Office: Hisao and Eli Morales Anne Thomson José Olaya #532 104 Lord Rutherford Road Huaraz, ANCASH Brightwater, NELSON PERU NEW ZEALAND Tele: 0051 (0)43 421864 Tele: 0064 (0)3 5424222 www.peruvianandes.com Email: [email protected] PERUVIAN ANDES ADVENTURES 2019 SUGGESTED GEAR LIST FOR TREKS & GENERAL INFORMATIOIN TREK GEAR LIST This is a suggested trek gear list – if you have any questions do please just email us We provide on trek: *Client tents / twin share – good quality grands * Foam sleeping mat + Thermorest inflatable mat (see note below re thermorest) *Cook tent *Dining tent with table & chairs *Toilet tent (Cordillera Blanca) with toilet paper, hand washing water & soap (In Cordillera Huayhuash the communities provide toilets in campsites) *All cooking equipment, stoves, gas, eating utensils, plates, cups etc *Oxygen bottle *Oxygen Saturation meter *Stretcher for emergency use *Bowl of hot water morning and afternoon for washing Double tent Thermorest & foam mat Dining Tent NOTE: THERMOREST INFLATABLE SLEEPING MAT We provide a Thermorest sleeping mat (free of charge) but the quality available in Peru to buy is not as reliable as international brand themorests. If you have your own good quality Thermorest inflatable sleeping mat, it can be a good idea to bring your own. You Need to provide: *Sleeping Bag – good quality 4 season sleeping bag. Night time temperatures can fall to as low as: Santa Cruz trek – as low as minus 2 to minus 5 degrees C Alpamayo Circuit treks – as low as minus 2 to minus 8 degrees C Huayhuash Treks – as low as minus 2 to minus 10 degrees C These are night time air temperatures. -

This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy Quaternary Science Reviews 28 (2009) 2165–2212 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quascirev Glaciation in the Andes during the Lateglacial and Holocene Donald T. Rodbell a,*, Jacqueline A. Smith b, Bryan G. Mark c a Geology Department, Union College, Schenectady, NY 12308, USA b Department of Physical and Biological Sciences, The College of Saint Rose, Albany, NY 12203, USA c Department of Geography, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA article info abstract Article history: This review updates the chronology of Andean glaciation during the Lateglacial and the Holocene from Received 23 March 2008 the numerous articles and reviews published over the past three decades. The Andes, which include Received in revised form some of the world’s wettest and driest mountainous regions, offer an unparalleled opportunity to 29 March 2009 elucidate spatial and temporal patterns of glaciation along a continuous 68-degree meridional transect. -

Taternik 3-4 2006

SPIS TREŚCI Sportowcy na rynku pracy (M. Słupińska) 1 Lato 2006 w Tatrach Polskich i okolicach (A. Paszczak) 2 BMC International Summer Rock Climbing Meet 2006 (J. Stefański) 6 Tryptyk Himalajski 2006 (P. Morawski) 9 Wyprawa na Makalu 2006 (A. Czerwińska) 13 K2'2006 - walka i katastrofa 15 Sage Symfonia Polish Karakoram Expedition 2006 (J. Radziejowski) 17 Wspinaczka w Karakorum (A. Pieprzycki) 20 Styl bazowy w Karakorum (R. Sławiński) 22 Polska droga w dolinie Cochamo (B. Kowalski) 26 W Cordillera Huayhuash (A. Sosgórnik) 27 Wiosną w dolinie Yosemite (A. Pustelnik) 28 Yosemite - Dolina przez wielkie „D" (Jarosław Liwacz) 30 Słońce i wiatr na grzebieniu (A. Śmiały) 33 Królestwo sępa (D. Kaszlikowski) 35 Zmagania wspinaczy sportowych (A. Kamiński) 37 Arabika 2005 (M. Mieszkowski) 41 Krótka relacja z jubileuszu Sekcji Grotołazów Wrocław (M. Mieszkowski) 42 Wyprawa speleologiczna Dolomiti Friulane 2006 Agnieszka Dziubek 44 V Międzynarodowy Konkurs Fotografii Jaskiniowej Im. Waldemara Burkackiego (K. Biernacka i K. Starosta) 45 „Egzotyczne" narciarstwo wysokogórskie (A. Huczko) 47 Rozmaitości 48 Osiem kręgów wtajemniczenia (W. Święcicki) 54 Wypadki taternickie w Polskich Tatrach (A. Marasek) 56 Jan Junger (1939 - 2005) 57 Jerzy Sznytzer (1935 - 2006) 57 Władysław Maciolowski (1928 - 2006) 58 Od redakcji 59 Okładka: Andrzej Marcisz na nowej drodze American Beauty na wschodniej ścianie Mnicha. Fot. T. Grzegorzewski Obok: Na drodze Alendelaca, Trinidad Sur. Fot. B.Kowalski IV strona okładki: Mnich w jesiennej oprawie. Fot. T. Grzegorzewski fssr^* TATERNIK Sportowcy na rynku pracy Magdalena Słupińska* Prawdopodobnie bywalcy strony internetowej Polskiego Związku Alpinizmu zauważyli, że od pewnego czasu umieszczone jest tam logo EFS EQUAL. Jest to znak, że PZA wraz z partnerami, którymi są Polski Związek Koszykówki, Polski Związek Piłki Siatkowej, Związek Piłki Ręcznej w Polsce, Fundacja Koszykówka Polska oraz Europrojekt, realizuje projekt finansowany ze środków Europejskiego Funduszu Społecznego Inicjatywy Wspólnotowej Eąual. -

Notes on Names of Peaks in the Cordillera Huayhuash. the Quechua of Different Regions of Peru Differs Considerably

Notes on Names of Peaks in the Cordillera Huayhuash. The Quechua of different regions of Peru differs considerably. On the eastern slope of the Cordillera Huayhuash it is quite different from that of the Cordillera Blanca. For that reason and because my investigations were limited to a few days, these findings are somewhat tentative. The maps of the Instituto Geográfico Militar of Peru seem to be excellent topo graphically but the nomenclature is hopelessly inaccurate; for instance the pampa on the southwestern shore of Lago Viconga is really Matipaqui (broken gourd) but it appears as Matiraqui on the map. Some of the names which appear on the map are completely unknown locally; on the southern rim of the range the peak which appears on the map as “Mito- punta” is actually called Yanacaico (black corral from yana (black) + caico (corral)), getting its name from the enclosed valley of the same name above which it rises. Jirishanca comes from jirish (hummingbird) + janca or shanca (cold place or snow mountain); there is no mention of the hummingbird’s bill, usually given as part of the meaning of the name, though this may be implied because of the shape of the peak. Ninashanca comes from nina (fire) + janca or shanca, possibly getting its name from red rock. Siulá means cold. Rasac means toad. Pus- canturpa means distaff. (The first part should be pronounced putskan, which signifies spinning.) Tsacra is an animal lair and Puyoc means rotten or moth-eaten. One informant told me that Sarapo means funnel, but this I could not confirm.