Insistent Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(2011) 1-17 Pūrṇabhadra's Pañcatantra Jaina Tales Or

International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) Vol. 7, No. 1 (2011) 1-17 PŪRṆABHADRA’S PAÑCATANTRA JAINA TALES OR BRAHMANICAL OUTSOURCING? McComas Taylor Introduction Jaiselmer is a fort-city on the old trade route that crossed the Thar desert in the far west of the state of Rajasthan. When Colonel James Tod visited Western India in the 1830s, he already knew by reputation of the Jaina community whom he called the “Oswals of Jessulmer” and their great library located beneath the Parisnath (Pārśvanātha) temple (Johnson 1992: 199). Georg Bühler, who visited Jaiselmer in 1873-74, found the Jaina library “smaller in extent than was formerly supposed”, but of “great importance”: “It contains a not inconsiderable number of very ancient manuscripts of classical Sanskrit poems and of books on Brahmanical Sastras, as well as some rare Jaina works. ... Besides the great Bhaṇḍār, Jesalmer is rich in private Jaina libraries” (Johnson 1992: 204). Long before Tod and Bühler’s visits, Jaiselmer had accommodated a thriving Jaina community and was an important seat of learning. Highly literate with a unique respect for writing (Johnson 1993: 189, Flügel 2005: 1), the Jaina community in Jaiselmer, like others all over India, were responsible for a prodigious literary output which formed great libraries known as “knowledge warehouses” (Cort 1995: 77). “Among the thousands of texts and hundreds of thousands of manuscripts in the Jain libraries of India, there are many narrative texts in all of the languages in which Jains have written. Some relate all or part of the Jain universal history: the lives of the twenty four Jinas of this era, as well as those of other heroes and exemplary people. -

Distinguishing the Two Siddhasenas

Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies, Vol. 48, No. 1, December 1999 Distinguishing the Two Siddhasenas FUJINAGA Sin Sometimes different philosophers in the same traditiion share the same name. For example, Dr. E. Frauwallner points out that there are two Buddhist philosophers who bear the name Vasubandu." Both of these philosophers are believed to have written important works that are attributed to that name. A similar situation can sometimes be found in the Jaina tradition, and sometimes the situation arises even when the philosophers are in different traditions. For exam- ple, there are two Indian philosophers who are called Haribhadra, one in the Jain tradition, and one in the Buddhist tradition. This paper will argue that one philosopher named Siddhasena, the author of the famous Jaina work, the Sammatitarka, should be distinguished from another philosopher with the same name, the author of the Nvavavatara, a work which occupies an equally important position in Jaina philosophy- 2) One reason to argue that the authors of these works are two different persons is that the works are written in two different languages : the Sammatitarka in Prakrit ; the Nvavavatara in Sanskrit. In the Jaina tradition, it is extremely unusual for the same author to write philosophical works in different languages, the usual languages being either Prakrit or Sanskrit, but not both. Of course, the possibility of one author using two languages cannot be completely eliminated. For example, the Jaina philosopher Haribhadra uses both Prakrit and Sanskrit. But even Haribhadra limits himself to one language when writing a philosophical .work : his philosophical works are all written in Sanskrit, and he uses Prakrit for all of his non-philosophical works. -

Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies

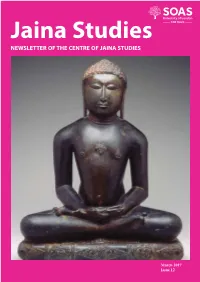

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2017 Issue 12 CoJS Newsletter • March 2017 • Issue 12 Centre of Jaina Studies Members SOAS MEMBERS Honorary President Professor Christine Chojnacki Muni Mahendra Kumar Ratnakumar Shah Professor J. Clifford Wright (University of Lyon) (Jain Vishva Bharati Institute, India) (Pune) Chair/Director of the Centre Dr Anne Clavel Dr James Laidlaw Dr Kanubhai Sheth Dr Peter Flügel (Aix en Province) (University of Cambridge) (LD Institute, Ahmedabad) Dr Crispin Branfoot Professor John E. Cort Dr Basile Leclère Dr Kalpana Sheth Department of the History of Art (Denison University) (University of Lyon) (Ahmedabad) and Archaeology Dr Eva De Clercq Dr Jeffery Long Dr Kamala Canda Sogani Professor Rachel Dwyer (University of Ghent) (Elizabethtown College) (Apapramśa Sāhitya Academy, Jaipur) South Asia Department Dr Robert J. Del Bontà Dr Andrea Luithle-Hardenberg Dr Jayandra Soni Dr Sean Gaffney (Independent Scholar) (University of Tübingen) (University of Marburg) Department of the Study of Religions Dr Saryu V. Doshi Professor Adelheid Mette Dr Luitgard Soni Dr Erica Hunter (Mumbai) (University of Munich) (University of Marburg) Department of the Study of Religions Professor Christoph Emmrich Gerd Mevissen Dr Herman Tieken Dr James Mallinson (University of Toronto) (Berliner Indologische Studien) (Institut Kern, Universiteit Leiden) South Asia Department Dr Anna Aurelia Esposito Professor Anne E. Monius Professor Maruti Nandan P. Tiwari Professor Werner Menski (University of Würzburg) (Harvard Divinity School) (Banaras Hindu University) School of Law Dr Sherry Fohr Dr Andrew More Dr Himal Trikha Professor Francesca Orsini (Converse College) (University of Toronto) (Austrian Academy of Sciences) South Asia Department Janet Leigh Foster Catherine Morice-Singh Dr Tomoyuki Uno Dr Ulrich Pagel (SOAS Alumna) (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle, Paris) (Chikushi Jogakuen University) Department of the Study of Religions Dr Lynn Foulston Professor Hampa P. -

Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies

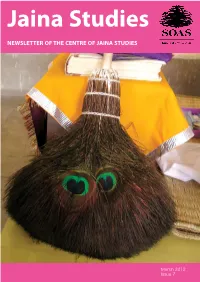

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2012 Issue 7 CoJS Newsletter • March 2012 • Issue 7 Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES Contents: 4 Letter from the Chair Conferences and News 5 Biodiversity Conservation and Animal Rights: Religious and Philosophical Perspectives: Programme 7 Biodiversity Conservation and Animal Rights: Religious and Philosophical Perspectives: Abstracts 11 The Paul Thieme Lectureship in Prakrit 12 Jaina Narratives: SOAS Jaina Studies Workshop 2011 15 SOAS Workshop 2013: Jaina Logic 16 Old Voices, New Visions: Jains in the History of Early Modern India at the AAS 18 How Do You ‘Teach’ Jainism? 20 Sanmarga: International Conference on the Influence of Jainism in Art, Culture & Literature 22 Jaina Studies Section at the 15th World Sanskrit Conference 24 Jiv Daya Foundation: Jainism Heritage Preservation Effort 24 Jaina Studies Certificate at SOAS Research 25 Stūpa as Tīrtha: Jaina Monastic Funerary Monuments 28 Peacock-Feather Broom (Mayūra-Picchī): Jaina Tool for Non-Violence 30 A Digambar Icon of 24 Jinas at the Ackland Art Museum 34 Life and Works of the Kharatara Gaccha Monk Jinaprabhasūri (1261-1333) 37 Jains in the Multicultural Mughal Empire 40 Fragile Virtue: Interpreting Women’s Monastic Practice in Early Medieval India Jaina Art 42 The Elegant Image: Bronzes at the New Orleans Museum of Art 45 Notes on Nudity in Digambara Jaina Art 47 Victoria & Albert Museum Jaina Art Fund 48 Continuing the Tradition: Jaina Art History in Berlin Publications 49 Jaina Studies Series 51 International Journal of Jaina Studies 52 International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) 52 Digital Resources in Jaina Studies at SOAS Prakrit Studies 53 Prakrit Courses at SOAS Jaina Studies at the University of London 54 Postgraduate Courses in Jainism at SOAS 54 PhD/MPhil in Jainism at SOAS 55 Jaina Studies at the University of London On the Cover The Peacock-Feather Broom (mayūra-picchī) of Āryikā Muktimatī Mātājī, in the Candraprabhu Digambara Jain Baṛā Mandira, in Bārābaṅkī/U.P. -

Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies

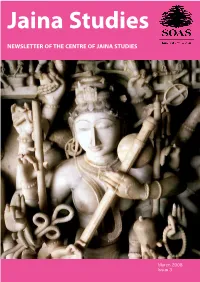

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2008 Issue 3 CoJS Newsletter • March 2008 • Issue 3 Centre for Jaina Studies' Members _____________________________________________________________________ SOAS MEMBERS EXTERNAL MEMBERS Honorary President Paul Dundas Professor J Clifford Wright (University of Edinburgh) Vedic, Classical Sanskrit, Pali, and Prakrit Senior Lecturer in Sanskrit language and literature; comparative philology Dr William Johnson (University of Cardiff) Chair/Director of the Centre Jainism; Indian religion; Sanskrit Indian Dr Peter Flügel Epic; Classical Indian religions; Sanskrit drama. Jainism; Religion and society in South Asia; Anthropology of religion; Religion and law; South Asian diaspora. ASSOCIATE MEMBERS Professor Lawrence A. Babb John Guy Dr Daud Ali (Amherst College) (Metropolitan Mueum of Art) History of medieval South India; Chola courtly culture in early medieval India Professor Nalini Balbir Professor Phyllis Granoff (Sorbonne Nouvelle) (Yale University) Professor Ian Brown The modern economic and political Dr Piotr Balcerowicz Dr Julia Hegewald history of South East Asia; the economic (University of Warsaw) (University of Heidelberg) impact of the inter-war depression in South East Asia Nick Barnard Professor Rishabh Chandra Jain (Victoria and Albert Museum) (Muzaffarpur University) Dr Whitney Cox Sanskrit literature and literary theory, Professor Satya Ranjan Banerjee Professor Padmanabh S. Jaini Tamil literature, intellectual (University of Kolkata) (UC Berkeley) and cultural history of South India, History of Saivism Dr Rohit Barot Dr Whitney M. Kelting (University of Bristol) (Northeastern University Boston) Professor Rachel Dwyer Indian film; Indian popular culture; Professor Bhansidar Bhatt Dr Kornelius Krümpelmann Gujarati language and literature; Gujarati (University of Münster) (University of Münster) Vaishnavism; Gujarati diaspora; compara- tive Indian literature. -

Chapter Four the Higher Ordination of Monkhood

CHAPTER FOUR THE HIGHER ORDINATION OF MONKHOOD 121 CHAPTER-IV The Higher Ordination of Monkhood 4. 0, Introduction Jainism is an ascetic religion from the very beginning. In Jainism grihastha stage is only a means to the higher goal of monk-hood. Jainism has retained its ascetic character till modem times. In Jaina tradition even a sravaka is taught yatidharma (the duty of an ascetic) prior to sravaka dharma, so that he is attracted by the life of a monk rather than remain attached to housenolder's lite. The whole moral code for a Jaina monk should be viewed from a particular angle. Here the aspirant has decided to devote himself absolutely to spirituaUsm. Even though depending on society for such bare necessities of hfe as food, he is above all social obhgations. His goal is transcendental moraUty which is beyond good or bad in the ordinary sense of the words. His life is predominated by niscayanaya or real point of view rather than by vyavaharanaya or practical point of view. In other words, to attain perfection, he has to avoid even smallest defects in his conduct even thought this may make his living odd and inconvenient from a worldly point of view.^^^ The institution of Jaina monkhood has been traced to pre-Vedic periods.'^^ The description of Rsabhadeva in the Bhagavata purana very '^•' Cf. Samksipta Mahabharata, (ed.). Vaidya, Bombay, 1921, Pp. 408-412 '"* Anekanta, Varta 10. Kirana 11-12, Pp. 433-456 122 much resembles the description of Jaina monk. Even though there has been some modifications in the moral code of a Jaina monk, which will be noted at places in this chapter, it is pointed out that the mode of living of a Jaina monk has essentially remained unchanged for all these ages. -

Mahäprasthäna, Präyopaveça, Sallekhana Viç-A-Viç Suicide

MAHÄPRASTHÄNA, PRÄYOPAVEÇA, SALLEKHANA VIÇ-A-VIÇ SUICIDE Lavanya Pravin Abstract It is well known that Çri Räma and his brothers entered the Sarayü and ended their lives. Yudhiñöhira, his wife and brothers started on mahäprasthäna; on their way each of them shed their mortal coils except Yudhisöhira. This is also a well-known story. In Tamil country Kopparuncholan, a Chola king and his longtime friend and poet Picirändaiyär left their mortal bodies by going into fasting (präyopaveça), seated facing the north, which is known as vaòakkirundu noṟṟal. Great yogis would go into samädhi and leave their body. All these methods of leaving one’s life on one’s own volition fall under the term mahäprasthäna. Sacrificing one’s life by undergoing sallekhana is a well-known practice of the Jains which has come to the court, recently, and is considered in the present day as committing suicide and hence a crime. The views of the Dharmaçätra on these issues are discussed here. In 2006, human activist Nikhil Soni and his lawyer Madhav Mishra filed a public interest litigation with the Rajasthan High court claiming Sallekhana to be suicide under the Indian legal statute. In August 2015 Rajasthan High court stated that the practice is not an essential tenet of Jainism and banned it making the practice punishable under section 306 and 309 (abetment of suicide) of the Indian Penal Code. On 24 th August 2015, the members of the Jain community held a peaceful nationwide protest against the ban. Silent marches were carried out in various states. On 31st August 2015, Supreme Court of India stayed the decision of 81 Rajasthan High court and lifted the ban and considered Sallekhana as a component of non-violence (Ahimsa). -

Muni Tarunsagarji

Muni TarunSagarji Muni TarunSagarji was born as Pawan Kumar Jain on 26 June 1967 to Pratap Chandra Jain and Shanti Bai Jain in a small village Guhanchi in Damoh, Madhya Pradesh, India. He was initiated as Kshullaka at the age of 13 and as a Digambara monk by Acharya Pushpdantsagar on 20 July 1988 in Bagidora, Rajasthan at the age of 20. He emerged as a prominent personality when GTV initiated a program called "MahaviraVani" In 2000, he gave an address from the Red Fort, Delhi. After wandering through Haryana (2000), Rajasthan (2001), Madhya Pradesh (2002), Gujrat (2003), Maharastra (2004), he arrived in Karnataka in 2006 for the occasion of Mahamastakabhisheka celebrations at Shravanabelagola after having walked for 65-days from Belgaum. By this time he had emerged as a "progressive Jain monk" for his criticism of violence, corruption and conservatism, and his speeches came to be called "KatuPravachan".He agreed to have his Chaturmas in Bangalore. While Jain monks often avoid associating with politicians, Muni TarunSagar has often met politicians and government officials as a guest. He has delivered his sermons in Madhya Pradesh Legislative Assembly on 2010 and in Haryana Legislative Assembly on 26 August 2016. His 2015 Chaturmas was in Shri 1008 Parshvanath Digambar Jain Mandir, where 108 Jain Śrāvaka pairs welcomed Muni Tarun Sagarji by washing his feet with 108 kalashas in 108 plates over a 200 feet ramp. He appeared on the talk show Aapki Adaalat hosted by Rajat Sharma on 18 march 2017 where he revealed that in childhood he liked the sweet Jalebi the most. -

Abstract Early Statements Relating to the Lay Community in the Svetambara Jain Canon Andrew More 2014

Abstract Early Statements Relating to the Lay Community in the Svetambara Jain Canon Andrew More 2014 In this thesis I examine various statements relating to the Jain lay community in the early Svetambara texts. My approach is deliberately and consistently historical. The earliest extant Svetambara writing presents an almost exclusively negative view of all non-mendicants. In the context of competition with other religious groups to gain the respect and material support of members of the general population, the Svetambara mendicants began to compose positive statements about a lay community. Instead of interpreting the key terms and formulations in these early statements anachronistically on the basis of the later and systematized account of lay Jain religiosity, I attempt to trace how the idea of lay Jainism and its distinctive practices gradually came into being. The more familiar account that is often taken as the basis for understanding earlier sources in fact emerges as the end product of this long history. This historical reconstruction poses numerous challenges. There is little reliable historical scholarship to draw from in carrying out this investigation. In the absence of a widely accepted account of the formation of the Svetambara canon, the dates of the canonical sources that I examine remain uncertain. I argue that by focusing on key passages relating to the Jain lay community it is possible to establish a relative chronology for the composition of some of these passages and for the compilation of some of the texts in which they appear. I thus suggest it is possible to observe development in the strategies employed by the mendicants as part of their effort to establish and maintain relations with a community of householders who respected and regularly supported them. -

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Educational Research

Volume 2, Issue 3, February 2013 International Journal of Multidisciplinary Educational Research Published by Dr.Victor Babu Koppula Department of Philosophy Andhra University, Visakhapatnam – 530 003 Andhra Pradesh – India Email: [email protected] website : www.ijmer.in Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief Dr. Victor Babu Koppula Department of Philosophy Andhra University – Visakhapatnam -530 003 Andhra Pradesh – India EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS Prof. S.Mahendra Dev Prof. (Dr.) Sohan Raj Tater Vice Chancellor Former Vice Chancellor Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research Singhania University , Rajasthan Mumbai Prof. G.Veerraju Prof.K.Sreerama Murty Department of Philosophy Department of Economics Andhra University Andhra University - Visakhapatnam Visakhapatnam Prof. K.R.Rajani Prof.G.Subhakar Department of Philosophy Department of Education Andhra University – Visakhapatnam Andhra University, Visakhapatnam Prof. A.B.S.V.Rangarao Dr.B.S.N.Murthy Department of Social Work Department of Mechanical Engineering Andhra University – Visakhapatnam GITAM University –Visakhapatnam Prof.S.Prasanna Sree N.Suryanarayana (Dhanam) Department of English Department of Philosophy Andhra University – Visakhapatnam Andhra University – Visakhapatnam Prof. P.Sivunnaidu Dr.Ch.Prema Kumar Department of History Department of Philosophy Andhra University – Visakhapatnam Andhra University – Visakhapatnam Prof. P.D.Satya Paul Dr. E.Ashok Kumar Department of Anthropology Department of Education Andhra University – Visakhapatnam North- Eastern Hill University, Shillong Dr. K. John Babu Dr.K.Chaitanya Department of Journalism & Mass Comm. Postdoctoral Research Fellow Acharya Nagarjuna University, Guntur Department of Chemistry Nanjing University of Science and Prof. Roger Wiemers Technology Professor of Education Xialingwei 200, Nanjing, 210094 Lipscomb University, Nashville, USA People’s Republic of China Dr.Merina Islam Dr. Zoran Vujisiæ Department of Philosophy Rector Cachar College, Assam St. -

JAIN CENTER of AMERICA SCHOLARS LECTURE SERIES at SIDDHACHALAM June 28-June 30, 2013

JAIN CENTER OF AMERICA SCHOLARS LECTURE SERIES AT SIDDHACHALAM June 28-June 30, 2013 Course Packet Dr. Jeffery D. Long Professor of Religion and Asian Studies Elizabethtown College Elizabethtown, PA (Author of Jainism: An Introduction ) Contents An Overview of Jainism , by Jeffery D. Long p. 3 From the web site of the World Religions & Spirituality Project VCU Virginia Commonwealth University (http://www.has.vcu.edu/wrs/profiles/Jainism.htm) Session A: Karma and Its Importance in the Jain Path p. 28 Karma is one of the most central concepts of Jainism, and of Indian spiritual traditions in general. The distinctive Jain understanding of karma will be examined from three perspectives: (a) the ways in which the Jain understanding of karma is unique among the Indian traditions, (b) how karma is presented in important Jain texts such as the Tattv !rtha S "tra , and (c) the practical application of the Jain understanding of karma to the spiritual path and to everyday life. Session B: Anek !ntv !d–The Jain Philosophy of the Diversity of p. 42 Worldviews Anek !ntv !d (Sanskrit: anek !ntav !da) is, along with ahi "s! and aparigraha, one of the three main principles of Jainism. It is also logically related to these other two principles. The relationship of anek !ntv !d to ahi "s! and aparigraha will be explored, as will the inner logic of this distinctive Jain doctrine. Anek !ntv !d teaches that reality is irreducibly complex. The nature of reality thus cannot be summarized in any simple metaphysical formula. Anek !ntv !d is a way of analyzing worldviews both critically and appreciatively, and forms a middle path between the extremes of absolutism and relativism. -

THE ART of DYING: Jain Philosophy of Sallekhana

26 November 9-15, 2019 JAINISM TheSouthAsianTimes.info THE ART OF DYING: Jain Philosophy of Sallekhana The news quickly spread through the Jain diaspora that two well-known monks embraced Sallekhana in just 2 months in India. Significantly, Sallekhana is NOT similarto euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide. It is the pious practice of voluntarily fasting to death by gradually reducing the intake of food and liquids. By Prof Shailendra C. Palvia death by gradually reducing the intake of food and liquids. This person should hilosophers have differed on the Acharya Vidyanandji endure all the hardships, but if he/she Psubject of Life after Death or rein‑ Last day of Sallekhana: September 19, 2019 falls ill or is unable to maintain the peace carnation. Aristotle holds the sci‑ of mind, then he/she should give up entific version while Plato and his mentor Sallekhana and resume taking foods and Socrates believed in the religious version. other activities. Sallekhana is considered Scientific premise asserts that after death, a pious death and is always voluntary, there is no life; it ends in eternal oblivion. undertaken after public declaration, and Religious premise states that only body never assisted with any chemicals or tools. perishes, soul survives forever; soul has The fasting causes thinning away of body eternal existence through countless cycles by withdrawing by choice food and water of birth and death. Sallekhana is relevant to oneself with full knowledge of more in the context of religious premise colleagues and spiritual counsellor. In due to the implication of afterlife better‑ some cases, Jains with terminal illness ment.