New Perspectives on Jain Architecture and Sculpture at Sravana Belagola

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations Among Diaspora Jains in the USA Venu Vrundavan Mehta Florida International University, [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-29-2017 An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA Venu Vrundavan Mehta Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC001765 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Mehta, Venu Vrundavan, "An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA" (2017). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3204. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3204 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF SECTARIAN NEGOTIATIONS AMONG DIASPORA JAINS IN THE USA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in RELIGIOUS STUDIES by Venu Vrundavan Mehta 2017 To: Dean John F. Stack Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs This thesis, written by Venu Vrundavan Mehta, and entitled An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. ______________________________________________ Albert Kafui Wuaku ______________________________________________ Iqbal Akhtar ______________________________________________ Steven M. Vose, Major Professor Date of Defense: March 29, 2017 This thesis of Venu Vrundavan Mehta is approved. -

Promote and Inter Society Business Jain World Business Directory Free Business Listing Only for Jain Organizat

Volume : 113 Issue No. : 113 Month : December, 2009 " EVERY SOUL IS INDEPENDENT, NONE DEPENDS ON ANOTHER, NONE IS SUPERIOR OR INFERIOR EVERY SOUL IS IN ITSELF ABSOLUTELY OMNISCIENT AND BLISSFUL, THE BLISS DOES NOT COME FROM OUTSIDE ALL HUMAN BEINGS ARE MISERABLE DUE TO THEIR OWN FAULTS AND THEY THEMSELVES CAN BE HAPPY BY CORRECTING THESE FAULTS" - Mahaveer – SAINTS 'INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHT IS A SOCIAL CRIME'- SAID SRIMAD ACHARYA VIJAY MAHARAJ SAHEB - Ahmedabad:"There was a time when knowledge was imparted freely. Unfortunately, today, knowledge has become highly commercialised," lamented Srimad Acharya Vijay Yugbhushan Surishwarji Maharaj Saheb also known as Pandit Maharaja, while inaugurating the Jyot Promote and Inter Society exhibition. The Acharya was addressing the devotees and knowledge Business seekers who flocked the 11-day exhibition presenting fundamental knowledge of Jainism in scientific manner, at SG Highway. Jain World Business Directory "No intellectual property rights or patent or royalty was demanded by the www.jainsamaj.org past generations for imparting traditional knowledge. However, today Free Business Listing only for Jain people demand patent and royalty for the innovations which is not very Organizations Around The World different from the traditional knowledge," said Pandit Maharaja. He also added that intellectual property right is a social exploitation of society. Click here to submit your company According to Pandit Maharaja the aim of organising the exhibition is to profile spread knowledge about the fundamentals of the Jainism. ENTRY FORM 'Jyot' showcases the various stages of development of the mankind. "The exhibition is not for entertainment but for the enlightenment of mankind," said Pandit Maharaja. -

President, Vice President and Prime Minister Greet the Nation

May, 2013 Vol. No. 153 Ahimsa Foundation in World Over + 1 Lakh The Only Jain E-Magazine Community Service for 13th Continuous Years Readership PRESIDENT, VICE PRESIDENT AND PRIME MINISTER GREET THE NATION Delivering the message to the nation on the eve of Mahavir Jayanti, President Pranab Mukherjee, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and Vice President Hamid Ansari greeted the nation. In his address to the nation, President Pranab Mukherjee expressed his heartiest greetings and good wishes to the people of India and to the Jain community in particular. Recalling the noble teachings of Lord Mahavira, Pranab Mukherjee appealed to people to give up violence in thought, word and deed and to always stick to the path of non-violence. Vice president Hamid Ansari in his message to the country said that Mahavir’s teachings of following the right belief and right conduct for the sake of human salvation is considered the most significant teaching forever. Requesting the people to follow the footsteps of Lord Mahavir, Ansari said that people should take the determination to follow his message in order to create a peaceful, non-violent and compassionate society. In his message to the people on the occasion, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh said, that, the noble philosophy of Mahavir is as relevant today with increasing incidents of crime and violence against vulnerable sections. The Prime Minister appealed to bring peace, prosperity and happiness to all countrymen. MAHAVIR JAYANTI GREETING FROM POPE BENEDICT'S OFFICE, VATICAN CITY Dear Jain Friends, 1. The Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue extends warm greetings and felicitations as you devoutly commemorate, on 23rd April this year, the Birth Anniversary of „Tirthankar’ Vardhaman Mahavir. -

Shiva's Waterfront Temples

Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Subhashini Kaligotla All rights reserved ABSTRACT Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla This dissertation examines Deccan India’s earliest surviving stone constructions, which were founded during the 6th through the 8th centuries and are known for their unparalleled formal eclecticism. Whereas past scholarship explains their heterogeneous formal character as an organic outcome of the Deccan’s “borderland” location between north India and south India, my study challenges the very conceptualization of the Deccan temple within a binary taxonomy that recognizes only northern and southern temple types. Rejecting the passivity implied by the borderland metaphor, I emphasize the role of human agents—particularly architects and makers—in establishing a dialectic between the north Indian and the south Indian architectural systems in the Deccan’s built worlds and built spaces. Secondly, by adopting the Deccan temple cluster as an analytical category in its own right, the present work contributes to the still developing field of landscape studies of the premodern Deccan. I read traditional art-historical evidence—the built environment, sculpture, and stone and copperplate inscriptions—alongside discursive treatments of landscape cultures and phenomenological and experiential perspectives. As a result, I am able to present hitherto unexamined aspects of the cluster’s spatial arrangement: the interrelationships between structures and the ways those relationships influence ritual and processional movements, as well as the symbolic, locative, and organizing role played by water bodies. -

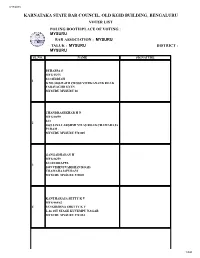

Mysuru Bar Association : Mysuru Taluk : Mysuru District : Mysuru

3/17/2018 KARNATAKA STATE BAR COUNCIL, OLD KGID BUILDING, BENGALURU VOTER LIST POLING BOOTH/PLACE OF VOTING : MYSURU BAR ASSOCIATION : MYSURU TALUK : MYSURU DISTRICT : MYSURU SL.NO. NAME SIGNATURE BYRAPPA S MYS/15/55 S/O SIDDIAH 1 D NO.3108/B 4TH CROSS VIVEKANAND ROAD YADAVAGIRI EXTN MYSURU MYSURU 20 CHANDRASEKHAR H N MYS/30/59 S/O 2 1065 JAYA LAKSHMI VILAS ROAD CHAMARAJA PURAM . MYSURU MYSURU 570 005 GANGADHARAN H MYS/36/59 S/O RUDRAPPA 3 1089 VISHNUVARDHAN ROAD CHAMARAJAPURAM MYSURU MYSURU 570005 KANTHARAJA SETTY K V MYS/484/62 4 S/O KRISHNA SHETTY K V L-26 1ST STAGE KUVEMPU NAGAR MYSURU MYSURU 570 023 1/320 3/17/2018 KRISHNA IYENGAR M S MYS/690/62 S/O M V KRISHNA IYENGAR 5 NO.1296 IV TH WEST CROSS 3RD MAIN ROAD KRISHNAMURTHYPURAM MYSURU MYSURU 04 SHIVASWAMY S A MYS/126/63 6 S/O APPAJIGOWDA SARASWATHIPURAM MYSURU MYSURU THONTADARYA MYS/81/68 S/O B.S. SIDDALINGASETTY 7 B.L 208 12TH MAIN 3RD CROSS SARASWATHIPURAM MYSURU MYSURU 570009 SRINIVASAN RANGA SWAMY MYS/190/68 S/O V R RANGASWAMY IGENGAL 8 416 VEENE SHAMANNA'S STREET OLD AGRAHARA MYSURU MYSURU 570 004 SESHU YEDATORE GUNDU RAO MYS/278/68 9 S/O Y.V.GUNDURAO YEDATORE 447/A-4 1 ST CROSS JAYA LAXMI VILAS ROAD MYSURU MYSURU 570 005 2/320 3/17/2018 RAMESH HAMPAPURA RANGA SWAMY MYS/314/68 S/O H.S. RANGA SWAMY 10 NO.27 14TH BLOCK SBM COLONY SRIRAMPURA 2ND STAGE MYSURU MYSURU 570023 ASWATHA NARAYANA RAO SHAM RAO MYS/351/68 11 S/O M.SHAMARAO 1396 D BLOCK KUVEMPUNAGAR MYSURU MYSURU 570023 SREENIVASA NATANAHALLY THIMME GOWDA MYS/133/69 S/O THIMMEGOWDA 12 NO 22 JAYASHREE NILAYA 12TH CROSS V.V.MOHALLA MYSURU MYSURU 2 DASE GOWDA SINGE GOWDA MYS/255/69 13 S/O SINGE GOWDA NO. -

The Rattas Patronage to Jainism

Aayushi International Interdisciplinary Research Journal (AIIRJ) UGC Approved Sr.No.64259 Vol - V Issue-I JANUARY 2018 ISSN 2349-638x Impact Factor 4.574 The Rattas Patronage to Jainism Dr.S.G. Chalawadi Asst. Professor, Dept of A I History and Epigraphy Karnatak University, Dharwad The Rattas were the significant ruling dynasty, who claimed descent from the Rastrakutas. The earliest record is dated 980 A.D. It comes from the place called sogal. It is believed that sogal was their early capital, from where they shifted first to Soundatti and later on to Belgaum. Their reign continued till 1238 A.D.1 When they were thrown out of power by the seunas of Devagiri. The Rattas served under the Chalukyas of Kalyan and tried to become independent. When the Kalachuries displaced 'the Chalukyas generally the Rattas claimed authority over a large administrative division known as Kohundi or kondi 3000. This included major parts of Soundatti, Gokak, Hukkeri, Raibag, Chikkodi, Bailhongal and Mudhol, Jamakhandi talukas which fall in Belgaum and Bijapur districts. The line of descent of Rattas rulers, commences with Nanna and ends with Lakshmideva - II. In between there were eleven rulers, namely Karthavirya-I, Nanna - I, Erga, Anka, Nanna-II, Karthavirya II, Sena-II, Karthavirya-III, Lakshmideva-I, Karthavirya-IV and Mallikarjuna- II. The Rattas in the course of their rule patronaged both saivism and Jainism. By erecting temples and Basadis and giving much grants to them. One of the earliest references to Jaina patronage under the Rattas is noticed in Soundatti inscription. We are told that Karthavirya-I gave land (grants) to the Basadis constructed by Pritvirama his successors Kannakaira also gave grants to Jinalya at Soundatti. -

Life of Mahavira As Described in the Jai N a Gran Thas Is Imbu Ed with Myths Which

T o be h a d of 1 T HE MA A ( ) N GER , T HE mu Gu ms J , A llahaba d . Lives of greatmen all remin d u s We can m our v s su m ake li e bli e , A nd n v hi n u s , departi g , lea e be d n n m Footpri ts o the sands of ti e . NGF LL W LO E O . mm zm fitm m m ! W ‘ i fi ’ mz m n C NT E O NT S. P re face Introd uction ntrod uctor remar s and th i I y k , e h storicity of M ahavira Sources of information mt o o ica stories , y h l g l — — Family relations birth — — C hild hood e d ucation marriage and posterity — — Re nou ncing the world Distribution of wealth Sanyas — — ce re mony Ke sh alochana Re solution Seve re pen ance for twe lve years His trave ls an d pre achings for thirty ye ars Attai n me nt of Nirvan a His disciples and early followers — H is ch aracte r teachings Approximate d ate of His Nirvana Appendix A PREF CE . r HE primary con dition for th e formation of a ” Nation is Pride in a common Past . Dr . Arn old h as rightly asked How can th e presen t fru th e u u h v ms h yield it , or f t re a e pro i e , except t eir ” roots be fixed in th e past ? Smiles lays mu ch ’ s ss on h s n wh n h e s s in his h a tre t i poi t , e ay C racter, “ a ns l n v u ls v s n h an d N tio , ike i di id a , deri e tre gt su pport from the feelin g th at they belon g to an u s u s h h th e h s of h ill trio race , t at t ey are eir t eir n ss an d u h u s of h great e , o g t to be perpet ator t eir is of mm n u s im an h n glory . -

Ahimsa and Vegetarianism

March , 2015 Vol. No. 176 Ahimsa Times in World Over + 100000 The Only Jain E-Magazine Community Service for 14 Continuous Years Readership AHIMSA AND VEGETARIANISM MAHARASHTRA GOVERNMENT BANS COW SLAUGHTER: FIVE YEARS JAIL Mar. 3rd, 2015. Mumbai. The bill banning cow slaughter in Maharashtra, pending for several years, finally received the President's assent, which means red meat lovers in the state will have to do without beef. This measure has taken almost twenty years to materialize and was initiated during the previous Sena-BJP Government. The bill was first submitted to the President for approval on January 30, 1996.. However, subsequent Governments at the Centre, including the BJP led NDA stalled it and did not seek the President’s consent. A delegation of seven state BJP MPs led by Kirit Somaiya, (MP from Mumbai North) had met the President in New Delhi recently and submitted a memorandum seeking assent to the bill. The memorandum said that the Maharashtra Animal Preservation (Amendment) Bill, 1995, passed during the previous Shiv Sena-BJP regime, was pending for approval for 19 years. The law will ban beef from the slaughter of bulls and bullocks, which was previously allowed based on a fit- for-slaughter certificate. The new Act will, however, allow the slaughter of water buffaloes. The punishment for the sale of beef or possession of it could be prison for five years with an additional fine of Rs 10,000. It is notable that, Reuters new service had earlier reported that Hindu nationalists in India had stepped up attacks on the country's beef industry, seizing trucks with cattle bound for abattoirs and blockading meat processing plants in a bid to halt the trade in the world's second-biggest exporter of beef. -

1995-96 and 1996- Postel Life Insurance Scheme 2988. SHRI

Written Answers 1 .DECEMBER 12. 1996 04 Written Answers (c) if not, the reasons therefor? (b) No, Sir. THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF (c) and (d). Do not arise. RAILWAYS (SHRI SATPAL MAHARAJ) (a) No, Sir. [Translation] (b) Does not arise. (c) Due to operational and resource constraints. Microwave Towers [Translation] 2987 SHRI THAWAR CHAND GEHLOT Will the Minister of COMMUNICATIONS be pleased to state : Construction ofBridge over River Ganga (a) the number of Microwave Towers targated to be set-up in the country during the year 1995-96 and 1996- 2990. SHRI RAMENDRA KUMAR : Will the Minister 97 for providing telephone facilities, State-wise; of RAILWAYS be pleased to state (b) the details of progress achieved upto October, (a) whether there is any proposal to construct a 1906 against above target State-wise; and bridge over river Ganges with a view to link Khagaria and Munger towns; and (c) whether the Government are facing financial crisis in achieving the said target? (b) if so, the details thereof alongwith the time by which construction work is likely to be started and THE MINISTER OF COMMUNICATIONS (SHRI BENI completed? PRASAD VERMA) : (a) to (c). The information is being collected and will be laid on the Table of the House. THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF RAILWAYS (SHRI SATPAL MAHARAJ) : (a) No, Sir. [E nglish] (b) Does not arise. Postel Life Insurance Scheme Railway Tracks between Virar and Dahanu 2988. SHRI VIJAY KUMAR KHANDELWAL : Will the Minister of COMMUNICATIONS be pleased to state: 2991. SHRI SURESH PRABHU -

Listing of Jain Books – 1

Listing of Jain Books – 1 Name Author Publisher Place/Year/# of Pages Ahimsa-The Science of Peace Surendra Bothara Prakrit Bharati Academy Jaipur 1937 132 Anekantvada Haristya Bhattacharya Sri Jaina Atmanand Sabha Bhavnagar 1953 208 Anekantvada-Central Philosophy of B. K. Motilal L. D. Indology Ahmedabad 1981 Jainism 72 Aspects of Jain Art and Architecture U. P. Shah and M. A. Dhaky Mahavir Nirvan Samiti, Gujarat Ahmedabad 1975 480 Aspects of Jaina monasticism Nathmal Tatia and Muni Today & Tomorrow Publi. New Delhi 1981 Mahendra Kumar 134 Atmasiddhi Shastra Shrimad Rajchandra Rajchandra Gyan Pracharak Ahmedabad 1978 Sabha 104 Bhagwan Mahavir and His Relevance Narendra Bhanawat Akhil Bharatvarshiya Sa. Jain Bikaner 221 In Modern Times Bright Once In Jainism J. L. Jaini Mahesh Chandra Jain Allahabad 1926 15 Canonical Litrature of Jainas H. R. Kapadia H. R. Kapadia Surat 1941 272 Comparative Study of (the) Jaina Y. J. Padmarajah Jain Sahitya Vikas Mandal Bombay 1963 Theories of Reality and Knowledge 423 Comparative Study of Jainism and Sital Prasad Sri Satguru Publi. Delhi 1982 Buddhism 304 Comprehensive History of Jainism Asim Kumar Chatterjee Firma KLM (P) Limited Calcutta 1978 400 Contribution of Jain Writers To Indian Buddha Malji Munshi Jain Swetambar Terapanthi Culcutta 1964 Languages Sabha, 28 Contribution of Jainism To Indian R. C. Dwivedi (Ed.) Motilal Banarasidas Delhi 1975 Culture 306 Cosmology : Old and New C. R. Jain The Trustees of The J.L.Jaini's Indore 1982 Estate 255 Dasaveyaliyasutta Ernst Leumann and Tr: The Manager of Sheth Anandji Ahmedabad 1932 Schubring Kalyanji 130 Dictionary of Jaina Biography Umrao Singh Tank Central Jaina Publishing Arrah 1917 House 132 Doctrine of Jainas Walter Schubring and Motilal Banarasidas Delhi 1978 Tr.Wohgang Beurlen 336 The Doctriness of Jainism Vallabhsuri Smarak Nidhi Bombay 1961 80 Doctrine of Karman In Jain Philosophy Helmuth Glasenapp. -

The Evolution of the Temple Plan in Karnataka with Respect to Contemporaneous Religious and Political Factors

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 22, Issue 7, Ver. 1 (July. 2017) PP 44-53 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org The Evolution of the Temple Plan in Karnataka with respect to Contemporaneous Religious and Political Factors Shilpa Sharma 1, Shireesh Deshpande 2 1(Associate Professor, IES College of Architecture, Mumbai University, India) 2(Professor Emeritus, RTMNU University, Nagpur, India) Abstract : This study explores the evolution of the plan of the Hindu temples in Karnatak, from a single-celled shrine in the 6th century to an elaborate walled complex in the 16th. In addition to the physical factors of the material and method of construction used, the changes in the temple architecture were closely linked to contemporary religious beliefs, rituals of worship and the patronage extended by the ruling dynasties. This paper examines the correspondence between these factors and the changes in the temple plan. Keywords: Hindu temples, Karnataka, evolution, temple plan, contemporary beliefs, religious, political I. INTRODUCTION 1. Background The purpose of the Hindu temple is shown by its form. (Kramrisch, 1996, p. vii) The architecture of any region is born out of various factors, both tangible and intangible. The tangible factors can be studied through the material used and the methods of construction used. The other factors which contribute to the temple architecture are the ways in which people perceive it and use it, to fulfil the contemporary prescribed rituals of worship. The religious purpose of temples has been discussed by several authors. Geva [1] explains that a temple is the place which represents the meeting of the divine and earthly realms. -

VII STD Social Science Term 3 History Chapter 1 New Religious Ideas and Movements

NEW BHARATH MATRICULATION HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL,TVR VII STD Social Science Term 3 History Chapter 1 New Religious Ideas and Movements I. Choose the correct answer: Question 1. Who of the following composed songs on Krishna putting himself in the place of mother Yashoda? (a) Poigaiazhwar (b) Periyazhwar (c) Nammazhwar (d) Andal Answer: (b) Periyazhwar Question 2. Who preached the Advaita philosophy? (a) Ramanujar (b) Ramananda (c) Nammazhwar (d) Adi Shankara Answer: (d) Adi Shankara Question 3. Who spread the Bhakthi ideology in northern India and made it a mass movement? (a) Vallabhacharya (b) Ramanujar (c) Ramananda (d) Surdas Answer: (c) Ramananda Question 4. Who made Chishti order popular in India? (a) Moinuddin Chishti (b) Suhrawardi (c) Amir Khusru (d) Nizamuddin Auliya Answer: (a) Moinuddin Chishti Question 5. Who is considered their first guru by the Sikhs? (a) Lehna (b) Guru Amir Singh (c) GuruNanak (d) Guru Gobind Singh Answer: (c) GuruNanak II. Fill in the Blanks. 1. Periyazhwar was earlier known as ______ 2. ______ is the holy book of the Sikhs. 3. Meerabai was the disciple of ______ 4. philosophy is known as Vishistadvaita ______ 5. Gurudwara Darbar Sahib is situated at ______ in Pakistan. Answer: 1. Vishnu Chittar 2. Guru Granth Sahib 3. Ravi das 4. Ramanuja’s 5. Karatarpur III. Match the following. Pahul – Kabir Ramcharitmanas – Sikhs Srivaishnavism – Abdul-Wahid Abu Najib Granthavali – Guru Gobind Singh Suhrawardi – Tulsidas Answer: Pahul – Sikhs Ramcharitmanas – Tulsidas Srivaishnavism – Ramanuja Granthavali – Kabir Suhrawardi – Abdul-Wahid Abu Najib IV. Find out the right pair/pairs: (1) Andal – Srivilliputhur (2) Tukaram – Bengal (3) Chaitanyadeva – Maharashtra (4) Brahma-sutra – Vallabacharya (5) Gurudwaras – Sikhs Answer: (1) Andal – Srivilliputhur (5) Gurudwaras – Sikhs Question 2.