7. Acut Gingival Diseases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral Diagnosis: the Clinician's Guide

Wright An imprint of Elsevier Science Limited Robert Stevenson House, 1-3 Baxter's Place, Leith Walk, Edinburgh EH I 3AF First published :WOO Reprinted 2002. 238 7X69. fax: (+ 1) 215 238 2239, e-mail: [email protected]. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier Science homepage (http://www.elsevier.com). by selecting'Customer Support' and then 'Obtaining Permissions·. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress ISBN 0 7236 1040 I _ your source for books. journals and multimedia in the health sciences www.elsevierhealth.com Composition by Scribe Design, Gillingham, Kent Printed and bound in China Contents Preface vii Acknowledgements ix 1 The challenge of diagnosis 1 2 The history 4 3 Examination 11 4 Diagnostic tests 33 5 Pain of dental origin 71 6 Pain of non-dental origin 99 7 Trauma 124 8 Infection 140 9 Cysts 160 10 Ulcers 185 11 White patches 210 12 Bumps, lumps and swellings 226 13 Oral changes in systemic disease 263 14 Oral consequences of medication 290 Index 299 Preface The foundation of any form of successful treatment is accurate diagnosis. Though scientifically based, dentistry is also an art. This is evident in the provision of operative dental care and also in the diagnosis of oral and dental diseases. While diagnostic skills will be developed and enhanced by experience, it is essential that every prospective dentist is taught how to develop a structured and comprehensive approach to oral diagnosis. -

Chronic Inflammatory Gingival Enlargement and Treatment: a Case Report

Case Report Adv Dent & Oral Health Volume 9 Issue 4- July 2018 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Mehmet Özgöz DOI: 10.19080/ADOH.2018.09.555766 Chronic Inflammatory Gingival Enlargement and Treatment: A Case Report Mehmet Özgöz1* and Taner Arabaci2 1Department of Periodontology, Akdeniz University, Turkey 2Department of Periodontology, Atatürk University, Turkey Submission: June 14, 2018; Published: July 18, 2018 *Corresponding author: Özgöz, Department of Periodontology, Akdeniz University Faculty of Dentistry, Antalya, Turkey, Fax:+902423106967; Email: Abstract Gingival enlargement is a common feature in gingival disease. If gingival enlargement isn’t treated, it may some aesthetic problems, plaque accumulation,Keywords: Gingival gingival enlargement; bleeding, and Periodontal periodontitis. treatments; In this paper, Etiological inflammatory factors; Plasma gingival cell enlargement gingivitis and treatment was presented. Introduction and retention include poor oral hygiene, abnormal relationship of Gingival enlargement is a common feature in gingival disease adjacent teeth, lack of tooth function, cervical cavities, improperly contoured dental restorations, food impaction, nasal obstruction, connection with etiological factors and pathological changes [3-5]. [1,2]. Many types of gingival enlargement can be classified in orthodontic therapy involving repositioning of the teeth, and habits such as mouth breathing and pressing the tongue against the gingival [18-20]. a)b) InflammatoryDrug-induced enlargement:enlargement [7-12]. chronic and acute [6]. c) Gingival enlargements associated with systemic diseases: patients to maintain oral hygiene [9,21]. Surgical correction of Overgrowth of the gingival tissue makes it more difficult for i. Conditioned enlargement (pregnancy, puberty, vitamin the gingival overgrowth is still the most frequent treatment. Such treatment is only advocated when the overgrowth is severe. -

Periodontal Health, Gingival Diseases and Conditions 99 Section 1 Periodontal Health

CHAPTER Periodontal Health, Gingival Diseases 6 and Conditions Section 1 Periodontal Health 99 Section 2 Dental Plaque-Induced Gingival Conditions 101 Classification of Plaque-Induced Gingivitis and Modifying Factors Plaque-Induced Gingivitis Modifying Factors of Plaque-Induced Gingivitis Drug-Influenced Gingival Enlargements Section 3 Non–Plaque-Induced Gingival Diseases 111 Description of Selected Disease Disorders Description of Selected Inflammatory and Immune Conditions and Lesions Section 4 Focus on Patients 117 Clinical Patient Care Ethical Dilemma Clinical Application. Examination of the gingiva is part of every patient visit. In this context, a thorough clinical and radiographic assessment of the patient’s gingival tissues provides the dental practitioner with invaluable diagnostic information that is critical to determining the health status of the gingiva. The dental hygienist is often the first member of the dental team to be able to detect the early signs of periodontal disease. In 2017, the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) and the European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) developed a new worldwide classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions. Included in the new classification scheme is the category called “periodontal health, gingival diseases/conditions.” Therefore, this chapter will first review the parameters that define periodontal health. Appreciating what constitutes as periodontal health serves as the basis for the dental provider to have a stronger understanding of the different categories of gingival diseases and conditions that are commonly encountered in clinical practice. Learning Objectives • Define periodontal health and be able to describe the clinical features that are consistent with signs of periodontal health. • List the two major subdivisions of gingival disease as established by the American Academy of Periodontology and the European Federation of Periodontology. -

Mouth Pain with Red Gums AMY M

Photo Quiz Mouth Pain with Red Gums AMY M. ZACK, MD, FAAFP; MIRCEA OLTEANU, DDS; and IYABODE ADEBAMBO, MD MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio The editors of AFP wel- On physical examination there was diffuse come submissions for erythema of the gums with mild edema and Photo Quiz. Guidelines for preparing and sub- tenderness. The patient had thick deposits mitting a Photo Quiz at the gum line that could not be wiped off. manuscript can be found There were areas of erythema, gum recession, in the Authors’ Guide at and increased movement of the teeth. There http://www.aafp.org/ afp/photoquizinfo. To be was pain when moving the teeth. There was no considered for publication, purulence, facial edema, or lymphadenopathy. submissions must meet Figure. these guidelines. E-mail Question submissions to afpphoto@ aafp.org. A 74-year-old man presented with pain in Based on the patient’s history and physical his mouth. The pain had been present for examination findings, which one of the fol- This series is coordinated by John E. Delzell, Jr., MD, a few months but had recently increased in lowing is the most likely diagnosis? intensity. He had not had recent dental work MSPH, Assistant Medical ❏ A. Dental abscess. Editor. and did not see a dentist regularly. He did not ❏ B. Dental caries. have a history of oral, head, or neck surgery. A collection of Photo Quiz ❏ C. Periodontal disease. published in AFP is avail- He did not have fever, chills, swelling of the ❏ D. Plaque gingivitis. able at http://www.aafp. face or neck, or discharge or drainage from org/afp/photoquiz. -

Successful Treatment of Persistent Bleeding from Gingival Ulcers in An

ISSN: 2469-5734 Masui et al. Int J Oral Dent Health 2018, 4:071 DOI: 10.23937/2469-5734/1510071 Volume 4 | Issue 2 International Journal of Open Access Oral and Dental Health CASE REPORT Successful Treatment of Persistent Bleeding from Gingival Ulcers in an Adolescent Patient with Irsogladine Maleate Atsushi Masui, Yoshihiro Morita, Takaki Iwagami, Masakazu Hamada, Hidetaka Shimizu * and Yoshiaki Yura Check for updates Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Osaka University Graduate School of Dentistry, Japan *Corresponding author: Yoshiaki Yura, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Osaka University Graduate School of Dentistry, 1-8 Yamadaoka, Suita, 565-0871, Japan docrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases, traumatic Abstract lesions, and gingival pigmentation. Persistent gingival Background: Gingival ulcer is often accompanied by se- bleeding occurs when the gingival mucosa becomes vere pain and bleeding and prevents the practicing of appro- priate oral hygiene. Most inflammatory and immune-mediat- fragile due to an inflammatory and immune-mediated ed gingival ulcers can be successfully treated with topical gingival disease and forms ulcers by a frictional proce- corticosteroids, but those refractory to corticosteroids are dure such as brushing [2-5]. Under these circumstances, difficult to treat. it is difficult to maintain oral hygiene, and so secondary Case description: An 18-year-old female visited our clinic dental biofilm-induced gingival diseases will be also in- with a complaint of gingival bleeding. Since topical cortico- duced. Most inflammatory and immune-mediated gin- steroids and oral antibiotic were not effective for gingival ul- gival diseases can be successfully treated with topical cers of the patient, an anti-gastric ulcer agent, irsogladine maleate, was used. -

Treating Patients with Drug-Induced Gingival Overgrowth

Source: Journal of Dental Hygiene, Vol. 78, No. 4, Fall 2004 Copyright by the American Dental Hygienists Association Treating Patients with Drug-Induced Gingival Overgrowth Ana L Thompson, Wayne W Herman, Joseph Konzelman and Marie A Collins Ana L. Thompson, RDH, MHE, is a research project manager and graduate student, and Marie A. Collins, RDH, MS, is chair & assistant professor, both in the Department of Dental Hygiene, School of Allied Health Sciences; Wayne W. Herman, DDS, MS, is an associate professor, and Joseph Konzelman, DDS, is a professor, both in the Department of Oral Diagnosis, School of Dentistry; all are at the Medical College of Georgia in Augusta, Georgia. The purpose of this paper is to review the causes and describe the appearance of drug-induced gingival overgrowth, so that dental hygienists are better prepared to manage such patients. Gingival overgrowth is caused by three categories of drugs: anticonvulsants, immunosuppressants, and calcium channel blockers. Some authors suggest that the prevalence of gingival overgrowth induced by chronic medication with calcium channel blockers is uncertain. The clinical manifestation of gingival overgrowth can range in severity from minor variations to complete coverage of the teeth, creating subsequent functional and aesthetic problems for the patient. A clear understanding of the etiology and pathogenesis of drug-induced gingival overgrowth has not been confirmed, but scientists consider that factors such as age, gender, genetics, concomitant drugs, and periodontal variables might contribute to the expression of drug-induced gingival overgrowth. When treating patients with gingival overgrowth, dental hygienists need to be prepared to offer maintenance and preventive therapy, emphasizing periodontal maintenance and patient education. -

Periodontal Health and Gingival Diseases

Received: 9 December 2017 Revised: 11 March 2018 Accepted: 12 March 2018 DOI: 10.1002/JPER.17-0719 2017 WORLD WORKSHOP Periodontal health and gingival diseases and conditions on an intact and a reduced periodontium: Consensus report of workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions Iain L.C. Chapple1 Brian L. Mealey2 Thomas E. Van Dyke3 P. Mark Bartold4 Henrik Dommisch5 Peter Eickholz6 Maria L. Geisinger7 Robert J. Genco8 Michael Glogauer9 Moshe Goldstein10 Terrence J. Griffin11 Palle Holmstrup12 Georgia K. Johnson13 Yvonne Kapila14 Niklaus P. Lang15 Joerg Meyle16 Shinya Murakami17 Jacqueline Plemons18 Giuseppe A. Romito19 Lior Shapira10 Dimitris N. Tatakis20 Wim Teughels21 Leonardo Trombelli22 Clemens Walter23 Gernot Wimmer24 Pinelopi Xenoudi25 Hiromasa Yoshie26 1Periodontal Research Group, Institute of Clinical Sciences, College of Medical & Dental Sciences, University of Birmingham, UK 2University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, USA 3The Forsyth Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA 4School of Dentistry, University of Adelaide, Australia 5Department of Periodontology and Synoptic Dentistry, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany 6Department of Periodontology, Center for Oral Medicine, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University Frankfurt, Germany 7Department of Periodontology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, USA 8Department of Oral Biology, SUNY at Buffalo, NY, USA 9Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto, Canada 10Department of Periodontology, Faculty of -

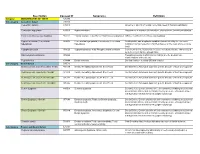

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition Category ABNORMALITIES OF TEETH 426390 Subcategory Cementum Defect 399115 Cementum aplasia 346218 Absence or paucity of cellular cementum (seen in hypophosphatasia) Cementum hypoplasia 180000 Hypocementosis Disturbance in structure of cementum, often seen in Juvenile periodontitis Florid cemento-osseous dysplasia 958771 Familial multiple cementoma; Florid osseous dysplasia Diffuse, multifocal cementosseous dysplasia Hypercementosis (Cementation 901056 Cementation hyperplasia; Cementosis; Cementum An idiopathic, non-neoplastic condition characterized by the excessive hyperplasia) hyperplasia buildup of normal cementum (calcified tissue) on the roots of one or more teeth Hypophosphatasia 976620 Hypophosphatasia mild; Phosphoethanol-aminuria Cementum defect; Autosomal recessive hereditary disease characterized by deficiency of alkaline phosphatase Odontohypophosphatasia 976622 Hypophosphatasia in which dental findings are the predominant manifestations of the disease Pulp sclerosis 179199 Dentin sclerosis Dentinal reaction to aging OR mild irritation Subcategory Dentin Defect 515523 Dentinogenesis imperfecta (Shell Teeth) 856459 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield I 977473 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield II 976722 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; -

Pathogenesis of Gingivitis and Periodontal Disease in Children and Young Adults Dr

PEDIATRIC DENTISTRY/Copyright ° 1981 by The American Academy of Pedodontics Vol. 3, Special Issue Pathogenesis of gingivitis and periodontal disease in children and young adults Dr. Ranney Richard R. Ranney, DOS, MS Bernard F. Debski, DMD, MS John G. Tew, PhD Abstract Introduction In adults and animal models, gingivitis consistently The most common forms of human periodontal dis- develops when bacterial plaque accumulates, and progresses ease are gingivitis and periodontitis. Gingivitis is sequentially through neutrophil, T-lymphocyte and B- defined as an inflammation of the gingiva. The gingiva lymphocyte/plasma cell dominated stages in a reproducible is all soft tissue surrounding the tooth coronal to the time frame. Periodontitis, also plasma cell dominated, crest of alveolar bone and to a varying extent lateral develops at a later time on the same regime, but with time- variability and less than 100% consistency. Gingivitis rarely to the bone, extending to the mucogingival junction. progresses to periodontitis in pre-pubertal children and On the other hand, the definition of periodontium in- seems to remain lymphocyte- rather than plasma cell- cludes cementum, periodontal ligament, alveolar bone, dominated. Bacteria are the accepted etiologic agents, with and the gingiva; and periodontitis includes loss of some particular species being associated with specific attachment of periodontal tissues from the tooth and clinical features; however, definitive correlations have not net loss of alveolar bone height.1 Gingivitis is reversi- been shown and a number of different species may be of ble, while regeneration after the destruction during etiologic significance in given cases. The signs of disease are periodontitis is not predictably achievable. -

DHY-209 Perio I

Bergen Community College Division of Health Professions Dental Hygiene Department Course Title: Periodontolgy I – DHY 209HY Term: Spring 2014 Hours/Credits: 1 Lecture hour/1 Credit Pre-Requisites: BIO-104, BIO-109, DHY-101, DHY- 108 and DHY-109 Class Day and Time: DHY 209-001 - Friday 10:30 AM – 11:20 AM DHY 209-002 - Friday 11:35 AM – 12:25 PM Classroom: Pitkin Education Center - B-322 Instructor: Denise D. Avrutik, RDH, MS Office Hours: Monday: 7:30 AM – 8:30 AM and 12:00 Noon – 12:30 PM Tuesday: 12:30 PM – 1:00 PM Wednesday: 7:30 AM – 8: 30 AM Also by appointment – Telephone: 201- 493-3628 Office: B-313 Email Address: [email protected] Textbook: Nield-Gehrig, J.S., Willmann, D., Foundations of Periodontics for the Dental Hygienist. Wolters, Kluwer/Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins. 3rd Edition, 2011. Instructional Resources: BCC Library and Resource Center Dental/Dental Hygiene Journals – National and International Web-based resources 1 | Asst. Prof. D. Avrutik – Periodontology I Syllabus (DHY 2 09) Internet Resources: www.adha.org (American Dental Hygienists’ Association) www.ada.org (American Dental Association) www.cochrane.org (Cochrane Reviews) http;//thePoint.lww.com - Periodontal Resources on the Internet – companion adjunct to your textbook. Course Description: This course is the study of the principles and concepts of periodontal disease including the tissues surrounding the teeth in both healthy and diseased states. Soft tissue management, periodontal therapies and case management are discussed. The role of systemic disease and periodontal health is also addressed. Prerequisites: BIO-104, BIO-109, DHY-101, DHY-108 and DHY-109 Course Objectives: Upon completion of the course, the student will be able to: Achieve accuracy in using periodontal terminology. -

Gingival Bleeding - Systemic Causes

European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine ISSN 2515-8260 Volume 07, Issue 5, 2020 Gingival Bleeding - Systemic Causes Dr. E.Rajes, Dr T. Alamelu Mangai, Dr.N.Aravindha Babu, Dr. L.Malathi Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, Sree Balaji Dental College and Hospital, Chennai. Bharath Institute of Higher Education and Research. ABSTRACT: Gingival bleeding is a common, mild form of gum disease. It is a primary sign of gingival disease such as gingival inflammation or Gingivitis is caused by accumulation of plaque at the gum line. Gingiva becomes swollen, reddish and irritable to the patient due to plaque accumulation. Plaque which is not removed will harden into tartar. This will lead to severe advanced gum disease and its progresses to periodontitis and finally tooth loss. Bleeding gums or Gingival Bleeding can cause discomfort to the patient both physically and mentally. Every dentist must know the underlying causes of gingival bleeding based on both local and systemic factors. This article aims to discuss the systemic causes of GINGIVAL BLEEDING. KEYWORDS: Gingival bleeding, Gingivitis, Bleeding gums, plaque, Gingival inflammation INTRODUCTION: Gingival bleeding is a primary symptom of gingival disease. The other systems are redness, inflammation of the gingiva, pain and difficulty in chewing. Primarily accumulation of plaque at the gum line is the cause for gingival bleeding. It will lead to Gum inflammation called gingivitis or inflamed gingiva. Bleeding on probing clinically is easily detectable and therefore of great value for the early diagnosis and prevention of more advanced Gingivitis 1. Bleeding gums appear earlier than change in color or any other visual signs of inflammation 2 .Gingival bleeding on probing indicates an inflammatory lesion both in the epithelium and in the connective tissue. -

Gingival Enlargement Management in Bir Hospital – a Case Series

Case Report J Nepal Soc Perio Oral Implantol. 2017;1(2):84-90 Gingival Enlargement Management in Bir Hospital – A Case Series Dr. Pramod Kumar Koirala,1 Dr. Shaili Pradhan,1 Dr. Ranjita Shrestha Gorkhali1 1Periodontology and Oral Implantology Unit, Department of Dental Surgery, National Academy of Medical Sciences, Bir Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal. ABSTRACT An increase in size of gingiva is a common clinical condition termed as gingival overgrowth. The definite aetiology is unknown. It is classified on the basis of aetiologic factors and pathologic changes. Both localised and generalised overgrowth are encountered commonly and patients are aesthetically, socially, psychologically and functionally disturbed until they revert back to the original contour. Localised gingival enlargement frequently is inflammatory and can also be associated with systemic diseases/condition (hormonal, nutritional, allergic, nonspecific conditioned) or neoplasic and sometimes false enlargement. DIGO is a well documented side effect with the use of anticonvulsant, immunosuppressant, and calcium channel blockers. Total 3% to 84.5% of subjects taking these drugs seem to have significant enlargement. Localised overgrowth are managed by proper diagnosis followed by controlling inflammation and other causative factors before surgical excision. DIGO is managed by drug replacement and surgical excision if required after nonsurgical treatment. Gingivoplasty of gingival margin is necessary to create self-cleansing and aesthetic architecture. Keywords: DIGO; gingival enlargement;