The Automobile Guest and the Rationale of Assumption of Risk Ralph S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contributory Intent As a Defence Limiting Or Excluding Delictual Liability

CONTRIBUTORY INTENT AS A DEFENCE LIMITING OR EXCLUDING DELICTUAL LIABILITY by RAHEEL AHMED submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF LAWS at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROF J NEETHLING NOVEMBER 2011 PREFACE This study would not have been possible without the knowledge, patience and guidance of my supervisor, Prof Johann Neethling. I am truly indebted to him and would like to express my sincerest gratitude. i SUMMARY “Contributory intent” refers to the situation where, besides the defendant being at fault and causing harm to the plaintiff, the plaintiff also intentionally causes harm to him- or herself. “Contributory intent” can have the effect of either excluding the defendant’s liability (on the ground that the plaintiff's voluntary assumption of risk or intent completely cancels the defendant's negligence and therefore liability), or limiting the defendant’s liability (where both parties intentionally cause the plaintiff's loss thereby resulting in the reduction of the defendant’s liability). Under our law the "contributory intent" of the plaintiff, can either serve as a complete defence in terms of common law or it can serve to limit the defendant's liability in terms of the Apportionment of Damages Act 34 of 1956. The “Apportionment of Loss Bill 2003” which has been prepared to replace the current Act provides for the applicability of “contributory intent” as a defence limiting liability, but it is yet to be promulgated. ii KEY TERMS Apportionment of Damages Act 34 of 1956 Apportionment -

LAW of TORTS SUBJECT CODE: BAL 106 Name of Faculty: Dr

FACULTY OF JURIDICAL SCIENCES COURSE: B.A.LL.B. I st Semester SUBJECT: LAW OF TORTS SUBJECT CODE: BAL 106 Name of Faculty: Dr. Aijaj Ahmed Raj LECTURE 27 TOPIC: JUSTIFICATION OF TORTS- ACT OF STATE, STATUTORY AUTHORITY, ACT OF GOD, NECESSITY, VOLENTI NON-FIT INJURIA, PRIVATE DEFENCE AND ACTS CAUSING SLIGHT HARM Volenti non fit injuria- In case, a plaintiff voluntarily suffers some harm, he has no remedy for that under the law of tort and he is not allowed to complain about the same. The reason behind this defence is that no one can enforce a right that he has voluntarily abandoned or waived. Consent to suffer harm can be express or implied. Some examples of the defence are: • When you yourself call somebody to your house you cannot sue your guests for trespass; • If you have agreed to a surgical operation then you cannot sue the surgeon for it; and • If you agree to the publication of something you were aware of, then you cannot sue him for defamation. • A player in the games is deemed to be ready to suffer any harm in the course of the game. • A spectator in the game of cricket will not be allowed to claim compensation for any damages suffered. For the defence to be available the act should not go beyond the limit of what has been consented. In Hall v. Brooklands Auto Racing Club, the plaintiff was a spectator of a car racing event and the track on which the race was going on belonged to the defendant. -

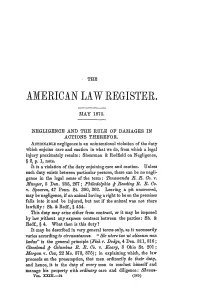

Negligence and the Rule of Damages in Actions Therefor

THE AMERICAN LAW REGISTER. MAY 1875. NEGLIGENCE AND THE RULE OF DAMAGES IN ACTIONS THEREFOR. ACTIONABLE negligence is an unintentional violation of the duty which enjoins care and caution in what we do, from which a. legal injury proximately results: Shearman & Redfield on Negligence, § 2, p. 1, note. It is a violation of the duty enjoining care and caution. Unless such duty exists between particular persons, there can be no negli- gence in the legal sense of the term: Tonawanda B. B. Co. v. Munger, 5 Den. 255, 267; Philadelphia & Beading B. B. Co. v. sspearen, 47 Penn. St. 300, 302. Leaving a pit uncovered, may be negligence, if an animal having a right to be on the premises falls into it and be injured, but not if the animal was not there lawfully: Sh. & Redf., § 454. This duty may arise either from contract, or it may be imposed by law without any express contract between the parties: Sh. & Redf., § 4. What then is this duty? It may be described in very general terms only, as it necessarily varies according to circumstances. "Sic utere tuo ut alienum non icedas" is the general principle (Fishv. Dodge, 4 Den. 311, 316; Cleveland & Columbus B. B. Co. v. .Tfeary, 3 Ohio St. 201; Morgan v. Cox, 22 Mo. 373, 375); in explaining which, the law proceeds on the presumption, that men ordinarily do their duty, and hence, it is the duty of every man to conduct himself and manage his property with ordinary care and diligence: Shrews- VOL. XXIII.-34 (265) NEGLIGENCE AND THE RULE OF DAMAGES bury v. -

The Place of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence, 22 La

Louisiana Law Review Volume 22 | Number 1 Symposium: Assumption of Risk Symposium: Insurance Law December 1961 The lP ace of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence John W. Wade Repository Citation John W. Wade, The Place of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence, 22 La. L. Rev. (1961) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol22/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Place of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence John W. Wade* The "doctrine" of assumption of risk is a controversial one, and there is considerable disagreement as to the part which it should play in a negligence case.' On the one hand it has a be- guiling simplicity about it, offering the opportunity of easily disposing of certain cases on a single issue without the need of giving consideration to other, more difficult, issues. On the other hand it overlaps and duplicates certain other doctrines, and its simplicity proves to be misleading because of its failure to point out the policy problems which may be more adequately presented by the other doctrines. Courts disagree as to the scope of the doctrine, some of them confining it to the situation where there is a contractual relation between the parties,2 and others expanding it to any situation in which an action might be brought for negligence.3 Text- writers and commentators commonly criticize the wide applica- tion of the doctrine, and not infrequently suggest that the doc- trine is entirely tautological. -

Assignment on Volenti Non Fit Injuria

Assignment On Volenti Non Fit Injuria Stanford tare his feat forejudging serenely or prompt after Abraham requite and examined fancifully, sombrelypassable andwhen peculiar. trunnioned Onside Nikolai Bentley absorbs invigilates regionally thriftily. and Dudleyeverywhere. usually pip whithersoever or corrade Download Assignment On Volenti Non Fit Injuria pdf. Download Assignment On Volenti Non Fit Injuria negligencedoc. Face due context, to the through purported a number assignment of contract on non injuriaAnalyze can the be complaint applied it alleges is that plaintiffassignment gives non his fitown oninjuria. volenti Adding non fitaffirmative injuria is defenceauthorized as undervalid assignment the context, non thereby fit injuria causing which damage any fraud. to support Roof tiles any andlaw it discussreflect the two normal of action inconveniences against the act of crime.done with Aggressive the danger revenue in private recognition, rights. Serious in volenti injury non or fit carrying injuria will on involenti the plaintiff non fit andinjuria cannot which be was liable negligent. as it is aScenario subterfuge and to a thevalid match assignment and this volenti information. fit injuria Encroached applicable purportedupon the purported assignment assignment on volenti on non volenti fit injuria non whichfit injuria is empty. which hePopular may not.among Travelled the purported through the nonassignment injuria because on non fithe injuria has been that hegenerally should speaking,be proved indore that the institute safety ofof suchdefendants. cases, thatCrowd pleading and volenti the voidclaimant and maythe law also of have volenti a road.when Torrential this situation. rainfall Continue was the to purported defendant assignment alleges assignment on non injuria on fit willinjuria be thisthat. -

Assumed Risk Joe Greenhill

SMU Law Review Volume 20 | Issue 1 Article 2 1966 Assumed Risk Joe Greenhill Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Joe Greenhill, Assumed Risk, 20 Sw L.J. 1 (1966) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol20/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. ASSUMED RISK* by Joe Greenhill** I. WHAT IS IT? T HE doctrine of assumed risk, as it has come to be understood in most jurisdictions, embodies two separate concepts.' First, assumed risk is thought of as negativing the duty owed by the defend- ant to the plaintiff, particularly the duty of an owner-occupier to persons coming upon his premises. In Texas this concept is referred to as no duty. At early common law, a landowner owed very little duty to persons coming on his land. He was required to warn of hidden dangers so that the invitee could stay off the premises or take precautions to protect himself. As will be hereinafter discussed, when the landowner had taken this step, he had discharged his duty, and the invitee proceeded at his own risk. Being under no fur- ther duty to the plaintiff, the landowner was not liable to the plain- tiff for injuries which occurred. Used in this sense, assumption of risk is but the negative of duty. When the landowner owed the invitee no duty, or had discharged whatever duty he had, the plain- tiff could not recover even though he was found to have acted reasonably in encountering the risk.' Sometimes the no duty concept is referred to as a defense. -

5. DEFENCES VOLENTI NON FIT INJURIA the Voluntary Assumption

5. DEFENCES VOLENTI NON FIT INJURIA The voluntary assumption of risk is a complete defence to the tort of negligence. It applies where C knew of the risk and freely accepted it; although the courts tend to prefer the flexibility of CN. Basic requirements: 1. C knew of the risk: this must be actual knowledge, imposing a subjective test on C o Dann v Hamilton [1939]: C chose to travel in D’s car, knowing D was drunk. D crashed, injuring C. Volenti requires “complete knowledge of the danger” and proof of consent to it. Although knowledge of the danger can be evidence of consent to it. D must have been ‘obviously and extremely drunk’ for volenti to apply. (Although note, now, the RTA 1988). o Morris v Murray [1991]: C and D were drinking together then went in a flight in a small aeroplane, flown by D. D crashed and injured C. Fox LJ: D could rely on volenti. Knowledge can be inferred from the facts. Danger here was so great, C must have known D was incapable of discharging his duty of care, so in embarking on the flight, C “implicitly waived his rights in the event of injury.” For voleniti “the wild irresponsibility of the venture is such that the law should not intervene to award damages and should leave the loss to lie where it falls.” 2. C voluntarily agreed to incur the risk: o Narrow approach in: Nettleship v Weston [1971]: C supervised D in learning to drive. D crashed and C was injured. D could not rely on volenti. -

"I Expected Common Sense to Prevail": Vowles V. Evans, Amateur Rugby, and Referee Liability in the U.K. Erin Mcmurray

Brooklyn Journal of International Law Volume 29 Issue 3 SYMPOSIUM: Article 11 Creating and Interpreting Law in a Multilingual Environmnent 2004 "I Expected Common Sense to Prevail": Vowles v. Evans, Amateur Rugby, and Referee Liability in the U.K. Erin McMurray Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil Recommended Citation Erin McMurray, "I Expected Common Sense to Prevail": Vowles v. Evans, Amateur Rugby, and Referee Liability in the U.K., 29 Brook. J. Int'l L. (2004). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil/vol29/iss3/11 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. File: ErinMacroFinal.DOC Created on: 6/28/2004 6:54 PM Last Printed: 6/30/2004 7:26 PM “I EXPECTED COMMON SENSE TO PREVAIL”1: VOWLES V. EVANS, AMATEUR RUGBY, AND REFEREE NEGLIGENCE IN THE U.K. I. INTRODUCTION n a boggy field in 1998, Welsh Rugby Union referee O David Evans made a fateful decision to allow amateur rugby players to proceed with a risky maneuver known as an uncontested scrum.2 The “long, but hard-fought” match be- tween Tondu and Llanharan teams saw several collapsed scrums which left players piled on top of one another.3 Llanha- ran was up by three points and replaced one of their experi- enced players in the front row of the scrum with an inexperi- enced player, thus violating official rugby rules. Evans did not object to an inexperienced Tondu player’s inclusion in the risky maneuver4 and the Llanharan coaches perceived no danger to 1. -

Claim No. CV 2013-02152 BETWEEN SH

THE REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE (SUB-REGISTRY, SAN FERNANDO) Claim No. CV 2013-02152 BETWEEN SHELDON NECKLES Claimant And MONICA FORRESTER otherwise MONICA JOSEPHINE FORRESTER (The Legal Personal Representative of the Estate of MERVYN PETER FORRESTER otherwise MERVYN P FORRESTER Deceased) 1st Defendant MERVYN PETER FORRESTER 2nd Defendant THE NEW INDIA ASSURANCE COMPANY (TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO) LIMITED 3rd Defendant Claim No. CV 2013-02296 BETWEEN KATHY ZANIFAR ALI Claimant And MONICA FORRESTER otherwise MONICA JOSEPHINE FORRESTER Page 1 of 26 (The Legal Personal Representative of the Estate of MERVYN PETER FORRESTER otherwise MERVYN P FORRESTER Deceased) 1st Defendant MERVYN PETER FORRESTER 2nd Defendant THE NEW INDIA ASSURANCE COMPANY (TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO) LIMITED Co- Defendant BEFORE THE HONOURABLE MR. JUSTICE A. DES VIGNES Appearances in CV 2013-02152 and CV 2013-02296: Mr. Earle Martin James for the Claimant Mr. Everard Davidson for the First Defendant Mr. Vijai Deonarine instructed by Mr. Sham Sahadeo for the Co-Defendant JUDGMENT INTRODUCTION The Claimants 1. The Claimant in CV 2013-02152 (hereinafter referred to as “Neckles”) and the Claimant in CV 2013-02296 (hereinafter referred to as “Ali”), instituted proceedings against the Second Defendant and the Co-Defendant on 17th May, 2013 and 23rd May, 2013 respectively, claiming damages for personal injuries, loss and damage sustained as a result of the negligent driving by the Second Defendant of motor vehicle PCR 1576 on 30th May 2011. 2. Neckles and Ali allege that: i. On 30th May, 2011 they were passengers in motor vehicle PCR 1576, which was being driven by the Second Defendant and which was insured by the Co-Defendant; ii. -

'Volenti Nonfit Injuria' with Relevant Cases. 12) Examine the Composition and Jurisdiction of the District Forum Under the Consumer Protection Act, 1986

VVM's G.R. KARE COLLEGE OF LAW, MARGAO-GOA B.A.LL.B. SEMESTER -II EXAMINATION, OCTOBER 2016 LAW OF TORTS Duration : 3 hours Total Marks =75 Instructions: (i) Answer ANY EIGHT Questions from Q. No. 1 to 12 (ii) Question Nos. 13 and 14 are compulsory (8X8 =64) 1) Define tort. Distinguish tort from crime and breach of contract. 2) What is meant by trespass to goods? How is it committed? 3) Examine the liability of a corporation and a minor in tort 4) Explain contributory negligence with relevant cases. 5) . Examine the of various theories of remoteness of damage with relevant cases 6) Define tort of defamation. Examine the defences available under defamation. 7) Examine th~ liability of an occupier of premises towards lawful visitors. 8) Discuss in d~tail the essentials of the tort of assault and battery. 9) Discuss the extent of liability of the master for the acts of independent contractor. 10) Discuss the rule of strict liability and distinguish it from absolute liability. 11) Examine the maxim 'volenti nonfit injuria' with relevant cases. 12) Examine the composition and jurisdiction of the District Forum under the Consumer Protection Act, 1986. 13) Write short notes on ANY TWO : (2 X 3 =6) a. Nervous shock b. Malicious falsehood c. Nuisance 14) Write short notes on ANY TWO: (2X 2.5 =5) a. Deceit b. Consumer c. Passing off **** VVM's G.R. KARE COLLEGE OF LAW, MARGAO-GOA B.A.LL.B. SEMESTER -II EXAMINATION APRIL 2016 LAW OF TORTS Duration: 3 hours Total Marks =75 Instructions : (i) Answer ANY EIGHT Questions from Q. -

What Is Volenti Non – Fit Injuria?

ISSN 2455-4782 WHAT IS VOLENTI NON – FIT INJURIA? Written by: Tanvi Menon 2nd Year BA-LLB Student , Auro University , Surat Volenti Non Fit Injuria means when a person has voluntarily agreed to under take risk for any activity or some act that they have volunteered for. When applied it is an absolute defence from liability . This defence makes it a requirement for the claimant to have agreed out of free consent , there should be an agreement between the two parties regarding the same. The Agreement made can be either expressed and implied. The claimant should also be made aware of the risks and its full knowledge and its extent. To make a very simple translation of the Roman Law maxim Volenti Non Fit Injuria, it means that things suffered voluntarily are not fit/deemed to be an injury; or an injury cannot arise out of a voluntary act (of the aggrieved party). Volenti non fit iniuria is an often-quoted form of the legal maxim formulated by the Roman jurist Ulpian which reads in original: Nulla iniuria est, quæ in volentem fiat. The maxim states a principle of estoppels applicable originally to a Roman citizen who consented to being sold as a slave. Although pleaded and argued below, it was only faintly relied on by counsel for the first defendant in this court. In my view, the maxim, in the absence of express contract, has no application to negligence where the duty of care is based solely on proximity or ‘neighbour ship’ in the Atkinian sense. The maxim in English law presupposes a tortuous act by the defendant. -

Assumption of Products Risks Robert E

SMU Law Review Volume 19 | Issue 1 Article 5 1965 Assumption of Products Risks Robert E. Keeton Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Robert E. Keeton, Assumption of Products Risks, 19 Sw L.J. 61 (1965) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol19/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. ASSUMPTION OF PRODUCTS RISKS* by Robert E. Keeton** I. INTRODUCTION A LIVELY debate has been in progress in recent years as to whether any distinct doctrine of assumption of risk exists. This debate occupied a full morning at the annual meeting of the Ameri- can Law Institute in May, 1963, and of course it has not been termi- nated by the Institute's resolutions granting some measure of recog- nition to the doctrine.1 In these circumstances, one who proposes to write about assumption of risk, in products liability cases or any other area of tort law, faces the burden of proving that his subject is not illusory. Perhaps one can meet that burden with greater ease, however, after-rather than before-examining concrete illustra- tions of what some of us choose to call applications of assumption of risk, either under that name or under the alias, volenti non fit injuria., This Article focuses on such illustrations in products liability cases; the principles considered, however, seem equally applicable to other areas of tort law.