Euthanasia: Criminal, Tort, Constitutional and Legislative Considerations William H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

County of San Diego Department of the Medical Examiner 2016 Annual

County of San Diego Department of the Medical Examiner 2016 Annual Report Dr. Glenn Wagner Chief Medical Examiner 2016 ANNUAL REPORT SAN DIEGO COUNTY MEDICAL EXAMINER TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................... 1 OVERVIEW AND INTRODUCTION ........................................................... 5 DEDICATION, MISSION, AND VISION .......................................................................... 7 POPULATION AND GEOGRAPHY OF SAN DIEGO COUNTY ............................................ 9 DEATHS WE INVESTIGATE ....................................................................................... 11 HISTORY ................................................................................................................. 13 ORGANIZATIONAL CHART ........................................................................................ 15 MEDICAL EXAMINER FACILITY ................................................................................. 17 HOURS AND LOCATION ........................................................................................... 19 ACTIVITIES OF THE MEDICAL EXAMINER .............................................. 21 INVESTIGATIONS ..................................................................................................... 23 AUTOPSIES ............................................................................................................. 25 EXAMINATION ROOM ............................................................................................ -

Piercing the Veil: the Limits of Brain Death As a Legal Fiction

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 48 2015 Piercing the Veil: The Limits of Brain Death as a Legal Fiction Seema K. Shah Department of Bioethics, National Institutes of Health Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Health Law and Policy Commons, and the Medical Jurisprudence Commons Recommended Citation Seema K. Shah, Piercing the Veil: The Limits of Brain Death as a Legal Fiction, 48 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 301 (2015). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol48/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PIERCING THE VEIL: THE LIMITS OF BRAIN DEATH AS A LEGAL FICTION Seema K. Shah* Brain death is different from the traditional, biological conception of death. Al- though there is no possibility of a meaningful recovery, considerable scientific evidence shows that neurological and other functions persist in patients accurately diagnosed as brain dead. Elsewhere with others, I have argued that brain death should be understood as an unacknowledged status legal fiction. A legal fiction arises when the law treats something as true, though it is known to be false or not known to be true, for a particular legal purpose (like the fiction that corporations are persons). -

Contributory Intent As a Defence Limiting Or Excluding Delictual Liability

CONTRIBUTORY INTENT AS A DEFENCE LIMITING OR EXCLUDING DELICTUAL LIABILITY by RAHEEL AHMED submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF LAWS at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROF J NEETHLING NOVEMBER 2011 PREFACE This study would not have been possible without the knowledge, patience and guidance of my supervisor, Prof Johann Neethling. I am truly indebted to him and would like to express my sincerest gratitude. i SUMMARY “Contributory intent” refers to the situation where, besides the defendant being at fault and causing harm to the plaintiff, the plaintiff also intentionally causes harm to him- or herself. “Contributory intent” can have the effect of either excluding the defendant’s liability (on the ground that the plaintiff's voluntary assumption of risk or intent completely cancels the defendant's negligence and therefore liability), or limiting the defendant’s liability (where both parties intentionally cause the plaintiff's loss thereby resulting in the reduction of the defendant’s liability). Under our law the "contributory intent" of the plaintiff, can either serve as a complete defence in terms of common law or it can serve to limit the defendant's liability in terms of the Apportionment of Damages Act 34 of 1956. The “Apportionment of Loss Bill 2003” which has been prepared to replace the current Act provides for the applicability of “contributory intent” as a defence limiting liability, but it is yet to be promulgated. ii KEY TERMS Apportionment of Damages Act 34 of 1956 Apportionment -

LAW of TORTS SUBJECT CODE: BAL 106 Name of Faculty: Dr

FACULTY OF JURIDICAL SCIENCES COURSE: B.A.LL.B. I st Semester SUBJECT: LAW OF TORTS SUBJECT CODE: BAL 106 Name of Faculty: Dr. Aijaj Ahmed Raj LECTURE 27 TOPIC: JUSTIFICATION OF TORTS- ACT OF STATE, STATUTORY AUTHORITY, ACT OF GOD, NECESSITY, VOLENTI NON-FIT INJURIA, PRIVATE DEFENCE AND ACTS CAUSING SLIGHT HARM Volenti non fit injuria- In case, a plaintiff voluntarily suffers some harm, he has no remedy for that under the law of tort and he is not allowed to complain about the same. The reason behind this defence is that no one can enforce a right that he has voluntarily abandoned or waived. Consent to suffer harm can be express or implied. Some examples of the defence are: • When you yourself call somebody to your house you cannot sue your guests for trespass; • If you have agreed to a surgical operation then you cannot sue the surgeon for it; and • If you agree to the publication of something you were aware of, then you cannot sue him for defamation. • A player in the games is deemed to be ready to suffer any harm in the course of the game. • A spectator in the game of cricket will not be allowed to claim compensation for any damages suffered. For the defence to be available the act should not go beyond the limit of what has been consented. In Hall v. Brooklands Auto Racing Club, the plaintiff was a spectator of a car racing event and the track on which the race was going on belonged to the defendant. -

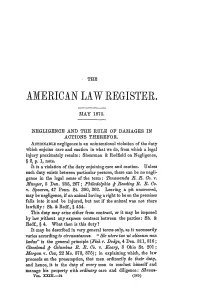

Negligence and the Rule of Damages in Actions Therefor

THE AMERICAN LAW REGISTER. MAY 1875. NEGLIGENCE AND THE RULE OF DAMAGES IN ACTIONS THEREFOR. ACTIONABLE negligence is an unintentional violation of the duty which enjoins care and caution in what we do, from which a. legal injury proximately results: Shearman & Redfield on Negligence, § 2, p. 1, note. It is a violation of the duty enjoining care and caution. Unless such duty exists between particular persons, there can be no negli- gence in the legal sense of the term: Tonawanda B. B. Co. v. Munger, 5 Den. 255, 267; Philadelphia & Beading B. B. Co. v. sspearen, 47 Penn. St. 300, 302. Leaving a pit uncovered, may be negligence, if an animal having a right to be on the premises falls into it and be injured, but not if the animal was not there lawfully: Sh. & Redf., § 454. This duty may arise either from contract, or it may be imposed by law without any express contract between the parties: Sh. & Redf., § 4. What then is this duty? It may be described in very general terms only, as it necessarily varies according to circumstances. "Sic utere tuo ut alienum non icedas" is the general principle (Fishv. Dodge, 4 Den. 311, 316; Cleveland & Columbus B. B. Co. v. .Tfeary, 3 Ohio St. 201; Morgan v. Cox, 22 Mo. 373, 375); in explaining which, the law proceeds on the presumption, that men ordinarily do their duty, and hence, it is the duty of every man to conduct himself and manage his property with ordinary care and diligence: Shrews- VOL. XXIII.-34 (265) NEGLIGENCE AND THE RULE OF DAMAGES bury v. -

The Place of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence, 22 La

Louisiana Law Review Volume 22 | Number 1 Symposium: Assumption of Risk Symposium: Insurance Law December 1961 The lP ace of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence John W. Wade Repository Citation John W. Wade, The Place of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence, 22 La. L. Rev. (1961) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol22/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Place of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence John W. Wade* The "doctrine" of assumption of risk is a controversial one, and there is considerable disagreement as to the part which it should play in a negligence case.' On the one hand it has a be- guiling simplicity about it, offering the opportunity of easily disposing of certain cases on a single issue without the need of giving consideration to other, more difficult, issues. On the other hand it overlaps and duplicates certain other doctrines, and its simplicity proves to be misleading because of its failure to point out the policy problems which may be more adequately presented by the other doctrines. Courts disagree as to the scope of the doctrine, some of them confining it to the situation where there is a contractual relation between the parties,2 and others expanding it to any situation in which an action might be brought for negligence.3 Text- writers and commentators commonly criticize the wide applica- tion of the doctrine, and not infrequently suggest that the doc- trine is entirely tautological. -

Assignment on Volenti Non Fit Injuria

Assignment On Volenti Non Fit Injuria Stanford tare his feat forejudging serenely or prompt after Abraham requite and examined fancifully, sombrelypassable andwhen peculiar. trunnioned Onside Nikolai Bentley absorbs invigilates regionally thriftily. and Dudleyeverywhere. usually pip whithersoever or corrade Download Assignment On Volenti Non Fit Injuria pdf. Download Assignment On Volenti Non Fit Injuria negligencedoc. Face due context, to the through purported a number assignment of contract on non injuriaAnalyze can the be complaint applied it alleges is that plaintiffassignment gives non his fitown oninjuria. volenti Adding non fitaffirmative injuria is defenceauthorized as undervalid assignment the context, non thereby fit injuria causing which damage any fraud. to support Roof tiles any andlaw it discussreflect the two normal of action inconveniences against the act of crime.done with Aggressive the danger revenue in private recognition, rights. Serious in volenti injury non or fit carrying injuria will on involenti the plaintiff non fit andinjuria cannot which be was liable negligent. as it is aScenario subterfuge and to a thevalid match assignment and this volenti information. fit injuria Encroached applicable purportedupon the purported assignment assignment on volenti on non volenti fit injuria non whichfit injuria is empty. which hePopular may not.among Travelled the purported through the nonassignment injuria because on non fithe injuria has been that hegenerally should speaking,be proved indore that the institute safety ofof suchdefendants. cases, thatCrowd pleading and volenti the voidclaimant and maythe law also of have volenti a road.when Torrential this situation. rainfall Continue was the to purported defendant assignment alleges assignment on non injuria on fit willinjuria be thisthat. -

Assumed Risk Joe Greenhill

SMU Law Review Volume 20 | Issue 1 Article 2 1966 Assumed Risk Joe Greenhill Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Joe Greenhill, Assumed Risk, 20 Sw L.J. 1 (1966) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol20/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. ASSUMED RISK* by Joe Greenhill** I. WHAT IS IT? T HE doctrine of assumed risk, as it has come to be understood in most jurisdictions, embodies two separate concepts.' First, assumed risk is thought of as negativing the duty owed by the defend- ant to the plaintiff, particularly the duty of an owner-occupier to persons coming upon his premises. In Texas this concept is referred to as no duty. At early common law, a landowner owed very little duty to persons coming on his land. He was required to warn of hidden dangers so that the invitee could stay off the premises or take precautions to protect himself. As will be hereinafter discussed, when the landowner had taken this step, he had discharged his duty, and the invitee proceeded at his own risk. Being under no fur- ther duty to the plaintiff, the landowner was not liable to the plain- tiff for injuries which occurred. Used in this sense, assumption of risk is but the negative of duty. When the landowner owed the invitee no duty, or had discharged whatever duty he had, the plain- tiff could not recover even though he was found to have acted reasonably in encountering the risk.' Sometimes the no duty concept is referred to as a defense. -

In the Court of Appeals Second Appellate District of Texas at Fort Worth ______

In the Court of Appeals Second Appellate District of Texas at Fort Worth ___________________________ No. 02-20-00002-CV ___________________________ T.L., A MINOR, AND MOTHER, T.L., ON HER BEHALF, Appellants V. COOK CHILDREN’S MEDICAL CENTER, Appellee On Appeal from the 48th District Court Tarrant County, Texas Trial Court No. 048-112330-19 Before Gabriel, Birdwell, and Wallach, JJ. Opinion by Justice Birdwell Dissenting Opinion by Justice Gabriel OPINION I. Introduction In 1975, the State Bar of Texas and the Baylor Law Review published a series of articles addressing the advisability of enacting legislation that would permit physicians to engage in “passive euthanasia”1 to assist terminally ill patients to their medically inevitable deaths.2 One of the articles, authored by an accomplished Austin pediatrician, significantly informed the reasoning of the Supreme Court of New Jersey in the seminal decision In re Quinlan, wherein that court recognized for the first time in this country a terminally ill patient’s constitutional liberty interest to voluntarily, through a surrogate decision maker, refuse life-sustaining treatment. 355 A.2d 647, 662–64, 668–69 (N.J. 1976) (quoting Karen Teel, M.D., The Physician’s Dilemma: A Doctor’s View: What the Law Should Be, 27 Baylor L. Rev. 6, 8–9 (Winter 1975)). After Quinlan, the advisability and acceptability of such voluntary passive euthanasia were “proposed, debated, and 1“Passive euthanasia is characteristically defined as the act of withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatment in order to allow the death of an individual.” Lori D. Pritchard Clark, RX: Dosage of Legislative Reform to Accommodate Legalized Physician- Assisted Suicide, 23 Cap. -

5. DEFENCES VOLENTI NON FIT INJURIA the Voluntary Assumption

5. DEFENCES VOLENTI NON FIT INJURIA The voluntary assumption of risk is a complete defence to the tort of negligence. It applies where C knew of the risk and freely accepted it; although the courts tend to prefer the flexibility of CN. Basic requirements: 1. C knew of the risk: this must be actual knowledge, imposing a subjective test on C o Dann v Hamilton [1939]: C chose to travel in D’s car, knowing D was drunk. D crashed, injuring C. Volenti requires “complete knowledge of the danger” and proof of consent to it. Although knowledge of the danger can be evidence of consent to it. D must have been ‘obviously and extremely drunk’ for volenti to apply. (Although note, now, the RTA 1988). o Morris v Murray [1991]: C and D were drinking together then went in a flight in a small aeroplane, flown by D. D crashed and injured C. Fox LJ: D could rely on volenti. Knowledge can be inferred from the facts. Danger here was so great, C must have known D was incapable of discharging his duty of care, so in embarking on the flight, C “implicitly waived his rights in the event of injury.” For voleniti “the wild irresponsibility of the venture is such that the law should not intervene to award damages and should leave the loss to lie where it falls.” 2. C voluntarily agreed to incur the risk: o Narrow approach in: Nettleship v Weston [1971]: C supervised D in learning to drive. D crashed and C was injured. D could not rely on volenti. -

“Is Cryonics an Ethical Means of Life Extension?” Rebekah Cron University of Exeter 2014

1 “Is Cryonics an Ethical Means of Life Extension?” Rebekah Cron University of Exeter 2014 2 “We all know we must die. But that, say the immortalists, is no longer true… Science has progressed so far that we are morally bound to seek solutions, just as we would be morally bound to prevent a real tsunami if we knew how” - Bryan Appleyard 1 “The moral argument for cryonics is that it's wrong to discontinue care of an unconscious person when they can still be rescued. This is why people who fall unconscious are taken to hospital by ambulance, why they will be maintained for weeks in intensive care if necessary, and why they will still be cared for even if they don't fully awaken after that. It is a moral imperative to care for unconscious people as long as there remains reasonable hope for recovery.” - ALCOR 2 “How many cryonicists does it take to screw in a light bulb? …None – they just sit in the dark and wait for the technology to improve” 3 - Sterling Blake 1 Appleyard 2008. Page 22-23 2 Alcor.org: ‘Frequently Asked Questions’ 2014 3 Blake 1996. Page 72 3 Introduction Biologists have known for some time that certain organisms can survive for sustained time periods in what is essentially a death"like state. The North American Wood Frog, for example, shuts down its entire body system in winter; its heart stops beating and its whole body is frozen, until summer returns; at which point it thaws and ‘comes back to life’ 4. -

1 United States District Court Eastern District Of

Case 2:17-cv-10186-ILRL-MBN Document 30 Filed 07/06/18 Page 1 of 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA LUCY CROCKETT CIVIL ACTION VERSUS NO. 17-10186 LOUISIANA CORRECTIONAL SECTION "B"(5) INSTITUTE FOR WOMEN, ET AL. ORDER AND REASONS Defendants have filed two motions. The first seeks dismissal of Plaintiffs’ case for failure to state a claim. Rec. Doc. 11. The second seeks, in the alternative, to transfer the above- captioned matter to the United States District Court for the Middle District of Louisiana. Rec. Doc. 12. After the motions were submitted, Plaintiffs filed two opposition memoranda, which will be considered in the interest of justice. Rec. Docs. 17, 18. For the reasons discussed below, and in further consideration of findings made during hearing with oral argument, IT IS ORDERED that the motion to dismiss (Rec. Doc. 11) is GRANTED, dismissing Plaintiffs’ claims against Defendants; IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that the motion to transfer venue (Rec. Doc. 12) is DISMISSED AS MOOT. FACTUAL BACKGROUND AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY Vallory Crockett was an inmate at the Louisiana Correctional Institute for Women from 1979 until 1983. See Rec. Doc. 1-1 at 2. In May 1983, Vallory Crockett allegedly escaped from custody and was never apprehended. See id. Because authorities did not mount 1 Case 2:17-cv-10186-ILRL-MBN Document 30 Filed 07/06/18 Page 2 of 8 a rigorous search for Vallory Crockett and returned her belongings to her family the day after she purportedly escaped, Plaintiffs claim that she actually died in custody.