Hockey Fans in Training: a Pilot Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Inductees

2020 Inductees GORD BROOKS Gord Brooks was born in Cobourg on September 11, 1950 and has the distinction of being Cobourg's first National Hockey League player. He played his minor hockey with the Cobourg Church Hockey League and spent the 1967‐68 season with Cobourg's Junior 'B' Cougars where he collected 21 goals, 26 assists and 44 minutes in penalties. Gord played his major Junior 'A' years with the Hamilton Red Wings and the London Knights. At the end of the 1969‐70 season, Gord Brooks was drafted 51st overall by the St. Louis Blues and spent his first professional season with their farm team, the Kansas City Blues. From 1971 to 1975, Gordie played 70 National Hockey League games with both the St. Louis Blues and the Washington Capitals. From 1975 to 1980, he played in the North American Hockey League and the American Hockey League where he truly made a name for himself. He played for both the Philadelphia Firebirds and Syracuse Firebirds, averaging 93 points a season for a total of 464. In 1977, his team won the Lockhart Cup as American Hockey League champions. In 1978, Gord won the John B. Sollenberger trophy as the American Hockey League's scoring champion and was named to the League's first All‐star team. In 1980, he played part of a season in Klagenfurt, Austria until a knee injury forced him out. The next year he joined the Saginaw Gears winning an international League championship. Two years after retiring as a pro, he came back to play Senior hockey for Brantford, winning an Allan Cup. -

Peterborough Petes 2018-19 Regular Season Media Guide

Peterborough Petes 2018-19 Regular Season Media Guide ROSTER Name Pos/Shot Ht Wt DOB OHL Draft 2017-18 Team Austin, Tye G/L 6.04 199 28-May-02 Pbo’s 3rd Rnd., 43 / ‘18 Kanata Lasers (HEOMAAA) Butler, Cameron RW/R 6.04 197 9-Jun-02 Pbo’s 2nd Rnd., 27 / ‘18 York-Simcoe Express (ETAMmHL) Čermák, Erik LW/L 5.11 154 2-Mar-01 Pbo’s CHL 2nd Rnd., 54 / ‘18 Red Bull Salzburg (Czech U18) Chisholm, Declan LD/L 6.01 188 12-Jan-00 Pbo's 2nd Rnd., 24 / '16 Peterborough Petes Curran, Blake G/L 6.01 176 15-Apr-99 Pbo’s U18 3rd Rnd., 55 / ‘17 Lindsay Muskies (OJHL) Denault, Chad RW/R 6.01 192 17-Apr-00 Pbo's 3rd Rnd., 49 / '16 Peterborough Petes Der-Arguchintsev, Semyon C/R 5.11 161 15-Sep-00 Pbo's 2nd Rnd., 27 / '16 Peterborough Petes Fraser, Cole RD/R 6.02 201 23-Aug-99 Pbo's 3rd Rnd., 50 / '15 Peterborough Petes Gallant, Zach C/L 6.02 192 6-Mar-99 Pbo's 1st Rnd., 5 / '15 Peterborough Petes Grondin, Max C/L 6.04 200 4-Jul-00 Sag’s 2nd Rnd., 37 / ‘16 Saginaw Spirit Hanna, Quinn D/R 6.03 205 14-Apr-99 Gue’s 5th Rnd., 64 / ‘15 Sherbrooke Phoenix (QMJHL) Hinz, Brady C/R 5.08 147 3-May-00 Sar’s 3rd Rnd., 52 / ‘16 Peterborough Petes Hutton, Dustin LW/R 5.09 145 22-Sep-01 Pbo’s U18 1st Rnd., 3 / ‘18 Vaughan Kings (GTHLMHL) Jones, Hunter G/L 6.04 194 21-Sep-00 Pbo's 5th Rnd., 89 / '16 Peterborough Petes Kirk, Liam LW/L 6.01 167 3-Jan-00 Pbo’s CHL 1st Rnd., 8 / ‘18 Sheffield Steelers (EIHL) Little, Michael LW/L 6.00 187 21-Feb-00 Miss’ 3rd Rnd., 59 / ‘16 Mississauga Steelheads Merkley, Ryan D/R 5.11 163 14-Aug-00 Gue’s 1st Rnd., 1 / ‘16 Guelph Storm McNamara, Matt RD/R 6.00 181 10-May-00 Pbo's 6th Rnd., 108 / '16 Peterborough Petes Osmanski, Austin RD/L 6.04 204 30-Apr-98 Miss’ 6th Rnd., 105 / ‘14 Peterborough Petes Paquette, Chris C/R 6.02 210 27-Mar-98 Nia’s 2nd Rnd., 30 / ‘14 Peterborough Petes Parker-Jones, John D/R 6.06.5 227 7-Apr-00 Free Agent Peterborough Petes Robertson, Nick C/L 5.08 156 11-Sept-01 Pbo’s 1st Rnd., 16 / ‘17 Peterborough Petes Spearing, Shawn LD/L 6.00 183 26-Jul-02 Pbo’s 4th Rnd., 75 / ‘18 Toronto Jr. -

Love Is GREAT Edition 1, March 2015

An LGBT guide Brought to you by for international media March 2015 Narberth Pembrokeshire, Wales visitbritain.com/media Contents Love is GREAT guide at a glance .................................................................................................................. 3 Love is GREAT – why? .................................................................................................................................... 4 Britain says ‘I do’ to marriage for same sex couples .............................................................................. 6 Plan your dream wedding! ............................................................................................................................. 7 The most romantic places to honeymoon in Britain ............................................................................. 10 10 restaurants for a romantic rendezvous ............................................................................................... 13 12 Countryside Hideaways ........................................................................................................................... 16 Nightlife: Britain’s fabulous LGBT clubs and bars ................................................................................. 20 25 year of Manchester and Brighton Prides .......................................................................................... 25 Shopping in Britain ....................................................................................................................................... -

Binghamton Senators: Player Profile (Doornbosch #2 and Englund #6)

Binghamton Senators: Player Profile (Doornbosch #2 and Englund #6) #2: Jamie Doornbosch (D) - Shoots: L (DORN-bosh) 6-2, 190 lbs. / Feb. 1, 1990 Drafted: Undrafted Birthplace: Richmond Hill, Ont. Last AHL Goal: NA Last AHL Assist: NA Regular Season Playoffs Year Team League GP G A PTS PIM +/- GP G A PTS PIM 2006-07 Markham Waxers OPJHL 1 0 0 0 0 0 2006-07 Peterborough Petes OHL 4 0 0 0 0 0 2007-08 Peterborough Petes OHL 60 2 10 12 53 -12 5 0 1 1 2 2008-09 Peterborough Petes OHL 64 8 29 37 60 -24 4 0 0 0 2 2009-10 Peterborough Petes OHL 68 12 38 50 52 -16 4 0 1 1 6 2010-11 Kitchener Rangers OHL 68 19 29 48 44 -4 7 1 1 2 8 2010-11 New York Islanders NHL 1 0 0 0 0 -1 2011-12 St. Mary's University AUS 28 1 13 14 70 -7 2012-13 St. Mary's University AUS 28 1 12 13 32 3 2013-14 St. Mary's University AUS 28 8 13 21 60 2014-15 St. Mary's University AUS 26 2 13 15 63 2015-16 St. Mary's University AUS 23 5 16 21 22 12 2016-17 Wichita Thunder ECHL 27 8 12 20 16 -17 2016-17 Binghamton Senators AHL 6 0 0 0 0 3 TOTAL AHL 6 0 0 0 0 3 0 0 0 0 0 Player Highlights - Named to the CIS Second All-Star Team in 2013-14 #6: Andreas Englund (D) - Shoots: L (AN-DRAY-us, ENG-lund) 6-4, 203 lbs. -

Hockey Fans in Training (Hockey FIT): Using CSR in Sport to Improve Fans’ Health

Hockey Fans in Training (Hockey FIT): Using CSR in Sport to Improve Fans’ Health Brendan Riggin (PhD Candidate) & Dr. Karen Danylchuk Researchers at Western University are teaming up with local hockey teams to address a growing social need – the health of overweight male sport fans. In Canada, 62% of men self- report as being overweight or obese (compared to 46% of women) and despite evidence that lifestyle programs can help reduce the risk of chronic disease, men are often under-represented in such programs (Gavarkovs, Burke, & Petrella, 2016; Statistics Canada, 2016). Sport fans, in particular, are at an even greater risk for chronic disease as they tend to weigh more, eat higher fat foods, and have worse general health habits than their non-sports fan counterparts (Sweeney & Quimby, 2012). This represents a large number of men in Canada, where 80% of the population considers ice hockey to be a key part of what it means to be Canadian and two-thirds of adults follow the sport as fans (The Environics Institute, 2012). In an attempt to utilize this knowledge, researchers developed the Hockey Fans in Training (Hockey FIT) program as an interdisciplinary project that leverages the passion male ice hockey fans feel towards their favourite Major Junior team to motivate them to join a 12-week healthy lifestyle program. The program was adapted from a successful program previously implemented within the UK called Football Fans in Training (FFIT). Each weekly session lasted 90 minutes and took place at the team’s arena or a local fitness facility. The sessions included off- ice hockey-related physical activity and education on evidence-based behaviour change techniques, healthy eating and physical activity, and setting lifestyle prescriptions for physical activity (steps/week). -

Peterborough Petes 2018 Training Camp

Peterborough Petes 2018 Training Camp ROSTER Name Pos/Shot Ht Wt DOB OHL Draft 2018-19 Team Austin, Tye G/L 6.05 198 28-May-02 Pbo’s 3rd Rnd., 43 / ‘18 Peterborough Petes Avon, Jon-Randall C/L 5.09.5 173 4-Jul-03 Pbo’s 1st Rnd., 11 / ‘19 Peterborough Petes (ETAMm) Butler, Cameron RW/R 6.04 196 9-Jun-02 Pbo’s 2nd Rnd., 27 / ‘18 Peterborough Petes Chiarot, Aaron RD/L 6.02 195 19-Mar-02 Pbo’s 9th Rnd., 162 / ‘18 Welland Jr. Canadians (GOJHL) Chisholm, Declan LD/L 6.01 185 12-Jan-00 Pbo's 2nd Rnd., 24 / '16 Peterborough Petes Curtin, Kyle G/L 6.02 155 12-Oct-01 Pbo’s U18 2nd Rnd., 23 / ‘18 St. Mary’s Lincolns (GOJHL) Cutler, Ryan RW/R 5.10.5 160 17-Dec-03 Pbo’s 12th Rnd., 235 / ‘19 York-Simcoe Express (ETAMm) Denault, Chad RW/R 6.01.5 190 17-Apr-00 Pbo's 3rd Rnd., 49 / '16 Peterborough Petes Der-Arguchintsev, Semyon C/R 5.10 159 15-Sep-00 Pbo's 2nd Rnd., 27 / '16 Peterborough Petes Dubois, Jax RW/R 6.00 175 18-Jun-03 Pbo’s 14th Rnd., 273 / ‘19 Nepean Raiders (HEOMAAA) Dunford, Bode LD/L 5.10 165 10-May-02 Free Agent Central Ontario Wolves (ETAMj) Edwards, Benjamin G/L 5.11.5 172 10-May-02 Pbo’s U18 2nd Rnd., 30 / ‘19 Toronto Titans (GTHLMj) Everson, Will LW/L 5.09.5 149 3-Dec-02 Free Agent Clarington Toros (ETAMj) Ferrier, Alex RD/R 6.02.5 191 4-May-02 Free Agent Central Ontario Wolves (ETAMj) Fortier, Sean LD/L 6.03 197 25-Jul-02 Free Agent Toronto Titans (GTHLMj) Gallant, Zach C/L 6.02 195 6-Mar-99 Pbo's 1st Rnd., 5 / '15 Peterborough Petes Grondin, Max C/L 6.03.5 199 4-Jul-00 Sag’s 2nd Rnd., 37 / ‘16 Peterborough Petes Guryev, Artem LD/L 6.02.5 192 17-May-03 Pbo’s 2nd Rnd., 22 / ‘19 Toronto Marlboros (GTHLMm) Hanna, Quinn RD/R 6.03.5 203 14-Apr-99 Gue’s 5th Rnd., 94 / ‘15 Peterborough Petes Haslam, Calum RD/R 5.11 195 31-Oct-02 Free Agent Vaughan Kings (GTHLMj) Heisler, Noah RD/L 6.01 176 20-Dec-00 Sar’s 14th Rnd., 277 / ‘16 Northfield Mount Hermon (USHS-Prep) Helmer, Cade C/L 6.00 165 3-May-01 Free Agent New Jersey Jr. -

2013-14 Hockey Hall of Fame Donor List

2013-14 Hockey Hall of Fame Donor List The Hockey Hall of Fame would like to express its sincere appreciation to the following donors: Leagues/Associations: American Hockey League, Canada West Universities Athletic Association, Canadian Deaf Ice Hockey Federation, Canadian Hockey League, Central Hockey League, College Hockey Inc., ECHL, National Hockey League, Ontario Hockey League, Quebec Major Junior Hockey League, United States Hockey League, Western Hockey League Companies/Organizations: Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame, CloutsnChara, Colin Barrow Toronto Valuations Inc., Ilitch Holdings, Inc., Maiquay Company Ltd., Nike Canada, Reebok CCM Hockey, The MeiGray Group, The Upper Deck Company IIHF Members: International Ice Hockey Federation, Austrian Ice Hockey Association, Hockey Canada, Finnish Ice Hockey Association, Hong Kong Ice Hockey Association Ltd., Hungarian Ice Hockey Federation, New Zealand Ice Hockey Federation, Ice Hockey Federation of Russia, Ice Hockey Federation of Slovenia, Ice Hockey UK Hockey Clubs: Alaska Aces, Anaheim Ducks, Brampton Beast, Chicago Blackhawks, Chicago Wolves, Clarkson University Golden Knights, Cornwall Colts, Dallas Stars, Dubuque Fighting Saints, Edmonton Oilers, Edmonton Oil Kings, Elrose Aces, Erie Otters, Färjestad BK, Guelph Storm, Indiana Ice, Iowa Wild, London Knights, Los Angeles Kings, Mettalurg Magnitogorsk, New Jersey Devils, North Bay Battalion, Nottingham Panthers, Peterborough Petes, Portland Winterhawks, Prince Albert Mintos, Rosetown Red Wings, St. Louis Blues, Texas Stars, Toronto Maple Leafs, Union College Dutchmen, Université de Montréal Carabins, University of Alberta Golden Bears, University of Saskatchewan Huskies, Utica Comets, Val d'Or Foreurs, Weyburn Gold Wings, Yale University Bulldogs, Yorkton Terriers Individuals: Jim Agnew, Michael Anscombe, Bill Armstrong, Camille Baccanale, Randy Baran, Charles "Rusty" Barton, Gerald Bayza, Annabel Begg, Barbara Benjamin, Aki Petteri Berg, Jonathan Bernier, Taylor Best, Kevin Bonish, Tyler Bozak, Claude R. -

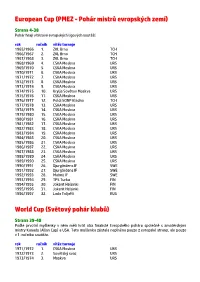

Europeancup (PMEZ

European Cup (PMEZ - Pohár mistrů evropských zemí) Strana 4-38 Pohár hrají vítězové evropských ligových soutěží. rok ročník vítěz turnaje 1965/1966 1. ZKL Brno TCH 1966/1967 2. ZKL Brno TCH 1967/1968 3. ZKL Brno TCH 1968/1969 4. CSKA Moskva URS 1969/1970 5. CSKA Moskva URS 1970/1971 6. CSKA Moskva URS 1971/1972 7. CSKA Moskva URS 1972/1973 8. CSKA Moskva URS 1973/1974 9. CSKA Moskva URS 1974/1975 10. Krylja Sovětov Moskva URS 1975/1976 11. CSKA Moskva URS 1976/1977 12. Poldi SONP Kladno TCH 1977/1978 13. CSKA Moskva URS 1978/1979 14. CSKA Moskva URS 1979/1980 15. CSKA Moskva URS 1980/1981 16. CSKA Moskva URS 1981/1982 17. CSKA Moskva URS 1982/1983 18. CSKA Moskva URS 1983/1984 19. CSKA Moskva URS 1984/1985 20. CSKA Moskva URS 1985/1986 21. CSKA Moskva URS 1986/1987 22. CSKA Moskva URS 1987/1988 23. CSKA Moskva URS 1988/1989 24. CSKA Moskva URS 1989/1990 25. CSKA Moskva URS 1990/1991 26. Djurgårdens IF SWE 1991/1992 27. Djurgårdens IF SWE 1992/1993 28. Malmö IF SWE 1993/1994 29. TPS Turku FIN 1994/1995 30. Jokerit Helsinki FIN 1995/1996 31. Jokerit Helsinki FIN 1996/1997 32. Lada Toljatti RUS World Cup (Světový pohár klubů) Strana 39-40 Podle prvotní myšlenky v něm měli hrát oba finalisté Evropského poháru společně s amatérskými mistry Kanady (Allan Cup) a USA. Tato myšlenka zůstala naplněna pouze z evropské strany, ale pouze v 1. ročníku soutěže. rok ročník vítěz turnaje 1971/1972 1. -

Hershey Bears 2017-18 Roster

HERSHEY BEARS 2017-18 ROSTER # NAME POS S HT WT DOB HOMETOWN 2016-17 TEAM DRAFTED CONTRACT 2 Tyler Lewington D R 6-2 202 12/5/1994 Edmonton, AB BEARS WSH, 7th (204), 2013 NHL 6 Lucas Johansen D L 6-2 182 11/16/1997 Vancouver, BC Kelowna (WHL) WSH, 1st (28), 2016 NHL 7 Connor Hobbs D R 6-1 197 1/4/1997 Regina, SK Regina (WHL) WSH, 5th (143), 2015 NHL 10 Dustin Gazley F R 5-8 164 10/3/1988 Novi, MI BEARS AHL 11 Zach Sill “A” F L 6-0 214 5/24/1988 Brookfield, NS BEARS NHL 12 Nathan Walker F L 5-9 186 2/7/1994 Cardiff, Wales BEARS WSH, 3rd (89), 2014 NHL 13 Jeremy Langlois F R 5-10 175 6/2/1990 Tempe, AZ Rockford AHL 14 Anthony Peluso F R 6-4 225 4/18/1989 Barrie, ON Manitoba STL, 6th (160), 2007 NHL 15 Travis Boyd F R 5-11 185 9/14/1993 Hopkins, MN BEARS WSH, 6th (177), 2011 NHL 17 Chris Bourque “A” F L 5-7 174 1/29/1986 Boston, MA BEARS WSH, 2nd (33), 2004 AHL 18 Wayne Simpson F R 5-11 194 11/19/1989 Boxboro, MA Providence NHL 19 Riley Barber F R 6-0 190 2/7/1994 Pittsburgh, PA Washington (NHL)/BEARS WSH, 6th (167), 2012 NHL 20 Liam O’Brien F L 6-1 215 7/29/1994 Halifax, NS Washington (NHL)/BEARS NHL 21 Joe Whitney F R 5-6 171 2/6/1988 Reading, MA San Antonio/Tucson AHL 22 Adam Chapie F R 6-1 186 7/6/1991 Oxford, MI Hartford/Greenville (ECHL) NHL 24 Tyler Graovac F L 6-5 208 4/27/1993 Brampton, ON Minnesota (NHL)/Iowa MIN, 7th (191), 2011 NHL 25 Colby Williams D R 6-0 199 1/26/1995 Regina, SK BEARS WSH, 6th (173), 2015 NHL 26 Mathias Bau F L 6-7 235 7/3/1993 Glostrup, Denmark Frederikshavn (Denmark) AHL 27 Aaron Ness D L 5-10 184 5/18/1990 Roseau, MN Washington (NHL)/BEARS NYI, 2nd (40), 2008 NHL 29 Tommy Hughes D R 6-2 225 4/7/1992 London, ON Hartford AHL 30 Vitek Vanecek G L 6-1 187 1/9/1996 Havlickuv Brod, Czech Republic BEARS WSH, 2nd (39), 2014 NHL 31 Pheonix Copley G L 6-4 200 1/18/1992 North Pole, AK St. -

IIHF Continental Cup (1997 – 2018)

IIHF Continental Cup (1997 – 2018) Year Winner 2nd 3rd 2017/18 Junost Minsk Nomad Astana Sheffield Steelers 2016/17 Nottingham Panthers Beibarys Atyrau Odense Bulldogs 2015/16 Rouen Dragons Herning Blue Fox GKS Tychy 2014/15 Neman Grodno Fischtown Pinguins Angers Ducs 2013/14 Stavanger Oilers Donbass Donetsk Asiago Hockey 2012/13 Donbass Donetsk Metallurg-Zhlobin Rouen Dragons 2011/12 Rouen Dragons HC Junost Minsk Donbass Donetsk 2010/11 HC Junost Minsk EC Red Bull Salzburg Sonderjysk Elitesport 2009/10 EC Red Bull Salzburg HC Junost Minsk Sheffield Steelers 2008/09 MHC Martin Rouen Dragons Bolzano Foxes 2007/08 Ak Bars Kazan HC Riga 2000 Kazzinc Torpedo 2006/07 Junost Minsk Avangard Omsk Ilves Tampere 2005/06 Lada Togliatti HC Riga 2000 ZSC Lions 2004/05 HKM Zvolen HC Dynamo Moskau Alba Volan 2003/04 HC Bratislava HC Gomel HC Lugano 2002/03 Jokerit Helsinki Lokomotiv Jaroslav HC Lugano 2001/02 ZSC Lions HC Milano Vipers HKM Zvolen 2000/01 ZSC Lions London Knights HC Bratislava 1999/00 HC Ambri Piotta Eisbären Berlin Ak Bars Kazan 1998/99 HC Ambri Piotta HC Kosice Avangard Omsk 1997/98 HC Kosice Eisbären Berlin Ilves Tampere SAM – Jan 2018 IIHF European Cup (1966 – 1997) Year Winner Year Winner 1997 Lada Togliatti (RUS) 1981 CSKA Moscow (URS) 1996 Jokerit Helsinki (FIN) 1980 CSKA Moscow (URS) 1995 Jokerit Helsinki (FIN) 1979 CSKA Moscow (URS) 1994 TPS Turku (FIN) 1978 CSKA Moscow (URS) 1993 Malmo IF (SWE) 1977 Poldi Kladno (TCH) 1992 Djurgardens IF, Stockholm (SWE) 1976 CSKA Moscow (URS) 1991 Djurgardens IF, Stockholm (SWE) 1975 Krylya Sovietov Moscow (URS) 1990 CSKA Moscow (URS) 1974 CSKA Moscow (URS) 1989 CSKA Moscow (URS) 1973 CSKA Moscow (URS) 1988 CSKA Moscow (URS) 1972 CSKA Moscow (URS) 1987 CSKA Moscow (URS) 1971 CSKA Moscow (URS) 1986 CSKA Moscow (URS) 1970 CSKA Moscow (URS) 1985 CSKA Moscow (URS) 1969 CSKA Moscow (URS) 1984 CSKA Moscow (URS) 1968 ZKL Brno (TCH) 1983 CSKA Moscow (URS) 1967 ZKL Brno (TCH) 1982 CSKA Moscow (URS) 1966 ZKL Brno (TCH) SAM – Jan 2018 . -

Media Kit Ontario Reign Vs Lake Erie Monsters Game #N-4

Media Kit Ontario Reign vs Lake Erie Monsters Game #N-4: Thursday, May 26, 2016 theahl.com Ontario Reign (7-5-0-0) vs. Lake Erie Monsters (10-2-0-0) May 26, 2016 -- Quicken Loans Arena AHL Game #N-4 GOALIES GOALIES # Name Ht Wt GP W L SO GAA SV% # Name Ht Wt GP W L SO GAA SV% 29 Michael Houser 6-2 190 1 0 0 0 0.00 1.000 30 Brad Thiessen 5-11 171 0 0 0 0 0.00 0.000 31 Peter Budaj 6-1 192 12 7 5 0 2.27 0.900 31 Anton Forsberg 6-2 176 5 4 0 1 1.52 0.947 35 Jack Flinn 6-8 233 0 0 0 0 0.00 0.000 70 Joonas Korpisalo 6-2 172 9 6 2 0 2.96 0.898 SKATERS SKATERS # Name Pos Ht Wt GP G A Pts. PIM +/- # Name Pos Ht Wt GP G A Pts. PIM +/- 3 Derek Forbort D 6-4 218 12 0 2 2 0 0 2 Steve McCarthy D 6-1 209 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 Kevin Gravel D 6-4 200 11 1 6 7 4 0 3 Dillon Heatherington D 6-4 220 12 0 3 3 4 0 5 Vincent LoVerde D 5-11 205 12 1 2 3 10 -1 4 Mark Cundari D 5-11 195 0 0 0 0 0 0 6 Paul LaDue D 6-1 205 2 0 0 0 0 -1 5 John Ramage D 6-0 200 1 0 0 0 0 1 7 Brett Sutter C 6-0 192 5 0 1 1 2 -3 6 Michael Paliotta D 6-3 207 5 0 0 0 0 6 8 Zach Leslie D 6-0 175 3 0 1 1 2 1 7 Nick Moutrey LW 6-3 222 1 0 0 0 2 0 9 Adrian Kempe LW 6-1 187 12 4 1 5 2 1 8 Zach Werenski D 6-2 209 12 4 7 11 2 6 10 Mike Amadio C 6-1 196 10 1 4 5 0 4 10 Paul Bittner LW 6-5 205 0 0 0 0 0 0 11 Kris Newbury C 5-11 213 12 1 2 3 17 -3 12 Ryan Craig LW 6-2 220 12 3 7 10 6 5 12 Jonny Brodzinski RW 6-0 202 4 2 1 3 2 2 13 Trent Vogelhuber LW 6-2 195 12 1 5 6 8 6 15 Paul Bissonnette LW 6-2 216 12 1 1 2 15 2 14 Dean Kukan D 6-2 209 12 1 2 3 2 0 16 Sean Backman RW 5-8 165 12 1 3 4 8 -1 16 Kerby Rychel LW 6-1 205 12 1 2 3 26 -4 17 Matt Leitner C 5-9 175 0 0 0 0 0 0 17 Blake Siebenaler D 6-1 185 0 0 0 0 0 0 18 Jordan Samuels-Thomas LW 6-4 210 12 1 0 1 8 -6 18 T.J. -

COMMUNITY REPORT MISSION Kroenke Sports Charities (KSC) Is Committed to Improving Lives Through the Spirit and Power of Sports

2019-20 COMMUNITY REPORT MISSION Kroenke Sports Charities (KSC) is committed to improving lives through the spirit and power of sports. We strive to serve our community through education, health and fitness initiatives, athletic programs, and direct aid, with the particular purpose of helping families, children, veterans, and the disabled. Kroenke Sports Charities provides relevant programs and support, directly and with other non-profit organizations, to ultimately assist, encourage, and enrich the lives of those in need. DEAR FRIENDS, Kroenke Sports Charities is proud to present our 2019-20 Report to the Community. This review is a compilation of our community efforts during the past season and expanded community response due to the novel Coronavirus pandemic. This season, it has been our privilege, and honor, to positively impact the lives of more than one million people through our education, health and fitness initiatives, athletic programs and direct aid. Sports provide a unifying platform bringing together diverse groups of people with a common passion that is also fun! Together, with our teams, staff and partners, we strive to make a lasting difference in the lives of our neighbors and friends. We hope this report conveys our mission to serve. We thank you for your partnership in making a difference in the community we call home. Sincerely, Deb Dowling Executive Director Kroenke Sports Charities 2 “I Have a Dream” Foundation of Boulder County 19th Special Forces Group, US Army 2HEARTS 3Hopeful Hearts 40 Hands 40 Days 4KidzSports