Lingerings of Light in a Dark Land : Being Researches Into the Past

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

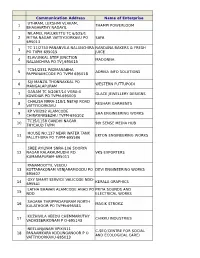

Communication Address Name of Enterprise 1 THAMPI

Communication Address Name of Enterprise UTHRAM, LEKSHMI VLAKAM, 1 THAMPI POWERLOOM BHAGAVATHY NADAYIL NILAMEL NALUKETTU TC 6/525/1 2 MITRA NAGAR VATTIYOORKAVU PO SAFA 695013 TC 11/2750 PANANVILA NALANCHIRA NANDANA BAKERS & FRESH 3 PO TVPM 695015 JUICE ELAVUNKAL STEP JUNCTION 4 MADONNA NALANCHIRA PO TV[,695015 TC54/2331 PADMANABHA 5 ADRIKA INFO SOLUTIONS PAPPANAMCODE PO TVPM 695018 SIJI MANZIL THONNAKKAL PO 6 WESTERN PUTTUPODI MANGALAPURAM GANAM TC 5/2067/14 VGRA-4 7 GLACE JEWELLERY DESIGNS KOWDIAR PO TVPM-695003 CHALISA NRRA-118/1 NETAJI ROAD 8 RESHAM GARMENTS VATTIYOORKAVU KP VIII/292 ALAMCODE 9 SHA ENGINEERING WORKS CHIRAYINKEEZHU TVPM-695102 TC15/1158 GANDHI NAGAR 10 9th SENSE MEDIA HUB THYCAUD TVPM HOUSE NO.137 NEAR WATER TANK 11 EKTON ENGINEERING WORKS PALLITHURA PO TVPM-695586 SREE AYILYAM SNRA-106 SOORYA 12 NAGAR KALAKAUMUDHI RD. VKS EXPORTERS KUMARAPURAM-695011 PANAMOOTTIL VEEDU 13 KOTTARAKONAM VENJARAMOODU PO DEVI ENGINEERING WORKS 695607 OXY SMART SERVICE VALICODE NDD- 14 KERALA GRAPHICS 695541 LATHA BHAVAN ALAMCODE ANAD PO PRIYA SOUNDS AND 15 NDD ELECTRICAL WORKS SAGARA THRIPPADAPURAM NORTH 16 MAGIK STROKZ KULATHOOR PO TVPM-695583 KUZHIVILA VEEDU CHEMMARUTHY 17 CHIKKU INDUSTRIES VADASSERIKONAM P O-695143 NEELANJANAM VPIX/511 C-SEC(CENTRE FOR SOCIAL 18 PANAAMKARA KODUNGANOOR P O AND ECOLOGICAL CARE) VATTIYOORKAVU-695013 ZENITH COTTAGE CHATHANPARA GURUPRASADAM READYMADE 19 THOTTAKKADU PO PIN695605 GARMENTS KARTHIKA VP 9/669 20 KODUNGANOORPO KULASEKHARAM GEETHAM 695013 SHAMLA MANZIL ARUKIL, 21 KUNNUMPURAM KUTTICHAL PO- N A R FLOUR MILLS 695574 RENVIL APARTMENTS TC1/1517 22 NAVARANGAM LANE MEDICAL VIJU ENTERPRISE COLLEGE PO NIKUNJAM, KRA-94,KEDARAM CORGENTZ INFOTECH PRIVATE 23 NAGAR,PATTOM PO, TRIVANDRUM LIMITED KALLUVELIL HOUSE KANDAMTHITTA 24 AMALA AYURVEDIC PHARMA PANTHA PO TVM PUTHEN PURACKAL KP IV/450-C 25 NEAR AL-UTHMAN SCHOOL AARC METAL AND WOOD MENAMKULAM TVPM KINAVU HOUSE TC 18/913 (4) 26 KALYANI DRESS WORLD ARAMADA PO TVPM THAZHE VILAYIL VEEDU OPP. -

Oskar's Guide

OSKAR’S GUIDE SOUTH INDIA TOUR And Extras January 2014 2 Specially prepared for Oskar Radosław Crick, second grandson of the author, Robert Gordon Crick On the occasion of his first overseas venture to the subcontinent of India Like many explorers, adventurers, treasure-seekers and conquerors before him, Oskar will be retracing their steps, learning of their experiences and accomplishments; but, more importantly, immersing himself in a totally new world that has its own unique history, culture and traditions. Hopefully, armed with these notes, motivated by wanting to discover new horizons and empowered by his own initiative and curiosity, he will return with a store of knowledge and experiences that will help define his future. Canberra and Gundaroo, January 2014 With due acknowledgement to a myriad of websites whose copyrights I have probably breached. Thanks especially to Wikipedia. 3 Table of Contents AN INTRODUCTION TO INDIA ............................................................................................................... 5 AN IMPRESSION OF INDIA..................................................................................................................... 6 STATES OF INDIA ................................................................................................................................... 7 WESTERN GHATS .................................................................................................................................. 7 KOCHI ................................................................................................................................................... -

10 Years Netherlands Funds-In-Trust Report

NIO M O UN IM D R T IA A L • P • W L O A I R D L D N H O E M R I E TA IN G O E • PATRIM United Nations World From Astronomy to Zanzibar – 10 Years of Dutch Support to World Heritage World Supportof Dutch to Years – 10 Zanzibar to Astronomy From Educational, Scientific and Heritage Cultural Organization Convention From stronomy Ato Zanzibar 10 Years of Dutch Support to World Heritage United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization NIO M O UN IM D R T IA A L • P • W L O A I R D L D N H O E M R I E TA IN G O E • PATRIM United Nations World Educational, Scientific and Heritage Cultural Organization Convention From stronomy Ato Zanzibar 10 Years of Dutch Support to World Heritage Cover Photos: © UNESCO/ R. Van Oers Supervision, editing and coordination: Ron van Oers and Sachiko Haraguchi, UNESCO World Heritage Centre Photos and images presented in the texts are the copyrights of the authors unless otherwise indicated. Published in 2012 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) 7 place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP France © UNESCO 2012 All rights reserved Disclaimer: The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The authors are responsible for the choice and the presentation of the facts contained in this book and for the opinions expressed therein, which are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. -

India & the Orient

INDIA & THE ORIENT A kaleidoscope of cultures, ancient empires and sensory adventures in Central Asia, India and the alluring lands of the Far East. 2019–2020 TRAVELS CONTENTS Li River, Yangshuo, China WHY CHOOSE AN A&K JOURNEY 2 TRULY LUXURIOUS ACCOMMODATION 4 HANDCRAFTED JOURNEYS 6 CELEBRATE FAMILY & FRIENDS 8 SINGAPORE AIRLINES 10 MARCO POLO CLUB | QANTAS FREQUENT 12 FLYER PROGRAMME A&K PHILANTHROPY 14 MAP 16 INDIA & BEYOND 18 India 22–45 Sri Lanka 46–53 Bhutan & Nepal 54–63 THE ORIENT 64 Southeast Asia 68 Vietnam 70–75 Laos 74–75, 82–83 Cambodia 72–77 Myanmar 78–81 Thailand 74–75, 82–83 Luxury Train Journeys 84–85 Myanmar Cruising 86 China & Central Asia 88–101 China 90–97 Uzbekistan & Turkmenistan 98–99 Mongolia 102–109 Japan 110–121 TERMS & CONDITIONS 122 EXPLORE MORE OF THE WORLD 124 IN A&K STYLE “Wherever you go, go with all your heart.” — Confucius Dear Traveller, It would be churlish of me, of all people, to admit to travel envy. Yet when our Australian office asked me to introduce this new India & Orient portfolio, my first thought was Australia really is the lucky country, blessed with so many of these extraordinary travel experiences so close to home. For me – as for many people who spent their formative years nearer the prime meridian than the International Dateline – India and ‘The Far East’ are synonymous with everything exquisite and exotic. When we established Abercrombie & Kent in the 1960s, luxury adventures in the Orient were always part of our plans. And we don’t do things by half-measures at A&K. -

(I) Concept of Heritage Museum

CONTENTS I. Introduction (i) Concept of Heritage Museum AHeritage Museum is a museum facility primarily dedicated to the presentation of historical and cultural information about a place and its people. The museum serves as a world of discovery, and uses exciting concepts to explore the history, architecture, art, culture and heritage of the place. The museum galleries through artifacts, installations and new technology present the history of the place. (ii) The Scope of the Project The main objective of the proposed Bastion Bungalow, Fort KochiDistrict Heritage Museum is to establish a “ MUSEUM ”in the context of the history, architecture, art, culture, and heritage of Ernakulam and Kochi, and the ancient trade and commerce, and the cosmopolitan culture of Fort Kochi. The purpose of establishing the museum is to trace and showcase the manifold facets of the origin and history of the city from the earliest times to the present. A complete set of basic drawings and plan of the museum is being shared. 2. Location of the Museum Bastion Bungalow, Fort Kochi is located in the heart of Fort Kochi, near the seashore and Vascoda Gama Square. The building is a protected monument of the Archaeology Department. The total area of the building is 542 square meters or approximately 5800 square feet. The conservation works of the building has beencompleted and the physical condition of the building is quite sound. A sketch of Bastion Bungalow showing the layout of the rooms is enclosed. 3. Fort Kochi Heritage Zone Kochi is located on the coast of the Arabian Sea, and is the commercial capital, and the most cosmopolitan city of Kerala. -

(A) CABLE CAR PROJECT in KOCHI

KERALA IRRIGATION INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD EXPRESSION OF INTEREST FOR CONSULTANTS FOR CABLE CAR PROJECT IN KOCHI Last Date of Submission: 30th March, 2020 KERALA IRRIGATION INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD (A Government of Kerala Undertaking) T.C. 36/1, NH Bypass Service Road, Near Eanchakkal Jn., Chackai P.O., Thiruvananthapuram 695024 DISCLAIMER 1. This EOI document is neither an agreement nor an offer by the KIIDC to the prospective Applicants or any other person. The purpose of this EOI is to provide information to the interested parties that may be useful to them in the formulation of their Bid pursuant to this EOI. 2. KIIDC will not be responsible for any delay in receiving the Proposals. The issue of this EOI does not imply that KIIDC is bound to select an Applicant or to appoint the successful applicant, as the case may be, for development and operation of Cable car services with other infrastructure. KIIDC reserves the right to accept/ reject any or all proposals submitted in response to this EOI document at any stage without assigning any reasons whatsoever. KIIDC also reserves the right to withhold or withdraw the process at any stage with intimation to all who submitted the EOI application. 3. The information given is not an exhaustive account of statutory requirements and should not be regarded as a complete or authoritative statement of law. KIIDC accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or otherwise for any interpretation or opinion on the law expressed herein. 4. KIIDC reserves the right to change/ modify/ amend any or all provisions of this EOI documents. -

Fromastronomy Tozanzibar

NIO M O UN IM D R T IA A L P W L O A I R D L D N H O E M R I E TA IN G O E PATRIM United Nations World From From Astronomy to Zanzibar – 10 of Years Dutch Support to World Heritage Heritage Cultural Organization Convention From stronomy Ato Zanzibar 10 Years of Dutch Support to World Heritage Cover Photos: © UNESCO/ R. Van Oers Supervision, editing and coordination: Ron van Oers and Sachiko Haraguchi, UNESCO World Heritage Centre Photos and images presented in the texts are the copyrights of the authors unless otherwise indicated. Published in 2012 by the United Nations Educational, Scienti!c and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) 7 place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP France © UNESCO 2012 All rights reserved Disclaimer: The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The authors are responsible for the choice and the presentation of the facts contained in this book and for the opinions expressed therein, which are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Composed and printed in the workshops of UNESCO The printer is certi!ed Imprim’Vert®, the French printing industry’s environmental initiative. CLT-2012/WS/5 – CLD 443.12 Table of Contents Foreword by Halbe Zijlstra, State Secretary of Education, Culture and Science of the Netherlands . -

State- Kerala

STATE- KERALA STATE DIST. CLASS SR. SR. NO. DISTRICT NO. SCHOOL NAME STUDENT NAME FATHER/MOTHER NAME AWARD CODE GUPS POOMTHOPPILBHAGAM, 1 ALAPPUZHA 1 7 GEETHU.T.A AJAYAKHOSH KLAL1000001 AVALOOKKUNNU.P.O,ALAPPUZHA TKMM UPS 2 ALAPPUZHA 2 VADACKAL,THIRUVAMPADY 7 VIDYA VEERAPPAN KLAL1000002 P.O,ALAPPUZHA 2 MMAUPS 3 ALAPPUZHA 3 VAZHICHERRY,VAZHICHERRYNORTH,A 7 SUMAYYA.A.S ABDULSALAM KLAL1000003 LAPPUZHA-1 UPS PUNNAPRA, 4 ALAPPUZHA 4 7 MANJUMADHU MADHU KLAL1000004 PUNNAPRA.P.O,ALAPPUZHA, ST,LOURDE MARY UPS 5 ALAPPUZHA 5 7 EDWINJAMES JAMES KLAL1000005 VADACKAL,ALAPPUZHA CYMA UPS CHRISOTHUROBINROBER 6 ALAPPUZHA 6 7 ROBERT KLAL1000006 PUNNAPRA,PUNNAPRA.P.O,ALPY, T VVSD UPS SOTH 7 ALAPPUZHA 7 ARYAD,SOUTHARYAD,PATHIRAPPALLY 7 MEERA BINU BINU.P KLAL1000007 , GUPS KALARCODE, 8 ALAPPUZHA 8 7 MARIYATH.A ABBAS KLAL1000008 SANATHANAPURAM.P.O.ALPY GUPS 9 ALAPPUZHA 9 THIRUVAMPADY,PAZHAVEEDU.P.O,AL 7 ARJUNSANKAR.S SIVADASAN KLAL1000009 APPUZHA GUPS ARYAD NORTH.,ARYADNORTH 10 ALAPPUZHA 10 7 SETHULEKSHMI.P.R P.S.RAMACHANDRAN KLAL1000010 P.O,ALAPPUZHA 11 ALAPPUZHA 11 SNDP UPS KARUVATTA 7 BABITHA THANKAPPAN KLAL1000011 12 ALAPPUZHA 12 GUPS NALUCHIRA 7 NIDHIN. S SHAJI KLAL1000012 13 ALAPPUZHA 13 ST.JAMES UPS KARUVATTA 7 ASWATHY.S ANAND.S KLAL1000013 14 ALAPPUZHA 14 KAM UPS PALLANA 7 AMMU.D LALI.V KLAL1000014 15 ALAPPUZHA 15 SDV GUPS NEERKUNNAM 7 RAKHIMOL RAJU P.V KLAL1000015 16 ALAPPUZHA 16 MMVM UPS THAMALLACKAL 7 KIRANKUMAR.K KARTHIKEYAN KLAL1000016 17 ALAPPUZHA 17 MT UPS THRIKKUNNAPPUZHA 7 SANDHYA THAMBI KLAL1000017 18 ALAPPUZHA 18 MU UPS ARATTUPUZHA 7 REVATHY.S -

List of Students Who Secured 10% Or Above Scores in Second Year

List of Students Who Secured 10% or above scores in Second Year Subjects of March 2020 Examination Revaluation The Principal should refund the amount collected from students towards revaluation fee for the following subjects Sl. No. Code School Name Reg No Candidate Name Subject 1 01001 GOVT MODEL BOYS HSS ATTINGAL 7000343 AISWARYA THULASI HISTORY 2 01001 GOVT MODEL BOYS HSS ATTINGAL 7000399 LEKSHMI PRAMOD COMPUTER APPLICATION-COM 3 01002 GOVT. GIRLS HSS, COTTONHILL, TRIVANDRUM 7000458 ANUPAMA RAVIKUMAR ENGLISH 4 01002 GOVT. GIRLS HSS, COTTONHILL, TRIVANDRUM 7000512 ANANYA I B ZOOLOGY 5 01002 GOVT. GIRLS HSS, COTTONHILL, TRIVANDRUM 7000673 ANN MARY LEONALD ENGLISH 6 01002 GOVT. GIRLS HSS, COTTONHILL, TRIVANDRUM 7000680 MARY NIRUPAMA M M ENGLISH 7 01002 GOVT. GIRLS HSS, COTTONHILL, TRIVANDRUM 7000767 RIYA SHAMS HINDI 8 01002 GOVT. GIRLS HSS, COTTONHILL, TRIVANDRUM 7000934 ANGEL MARIAM JOSE ENGLISH 9 01002 GOVT. GIRLS HSS, COTTONHILL, TRIVANDRUM 7000971 AISWARYA DAS S ENGLISH 10 01002 GOVT. GIRLS HSS, COTTONHILL, TRIVANDRUM 7000971 AISWARYA DAS S ECONOMICS 11 01005 GOVT HSS, KILIMANOOR, TRIVANDRUM 7001404 FATHIMA.S HISTORY 12 01005 GOVT HSS, KILIMANOOR, TRIVANDRUM 7001505 GREESHMA .V.J ENGLISH 13 01005 GOVT HSS, KILIMANOOR, TRIVANDRUM 7001578 REVATHY.V.L ENGLISH 14 01006 GOVT.GIRLS HSS,MANACAUD, TRIVANDRUM 7001599 ARUJA.M.J MALAYALAM 15 01006 GOVT.GIRLS HSS,MANACAUD, TRIVANDRUM 7001603 ASIYA S. ANVER MALAYALAM 16 01006 GOVT.GIRLS HSS,MANACAUD, TRIVANDRUM 7001612 DEVIKA P.S. ZOOLOGY 17 01006 GOVT.GIRLS HSS,MANACAUD, TRIVANDRUM 7001681 DEEPIKA. S. R BOTANY 18 01006 GOVT.GIRLS HSS,MANACAUD, TRIVANDRUM 7001769 AJILA .S SOCIOLOGY 19 01006 GOVT.GIRLS HSS,MANACAUD, TRIVANDRUM 7001799 FOUSIYA L SOCIOLOGY 20 01006 GOVT.GIRLS HSS,MANACAUD, TRIVANDRUM 7001827 PARVATHY GOPAN ECONOMICS 21 01006 GOVT.GIRLS HSS,MANACAUD, TRIVANDRUM 7001827 PARVATHY GOPAN SOCIOLOGY 22 01006 GOVT.GIRLS HSS,MANACAUD, TRIVANDRUM 7001934 SARANYA CHANDRAN R D COMPUTER APPLICATION-COM 23 01007 GOVT. -

The Anglo Indian Community in Kerala

THE ANGLO INDIAN COMMUNITY IN KERALA Thesis submitted to the University of Kerala for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By K. V. THOMASKUTTY Principal St.Johns College, Anchal KERALA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY THIRUVANANTHAPURAM September 2012 1 DR. T. JAMAL MOHAMMED Charitham, Kariavattom Thiruvananthapuram CERTIFICATE Certified that the thesis entitled THE ANGLO INDIAN COMMUNITY IN KERALA submitted for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of University of Kerala is a record of bonafied research work carried out by K. V. THOMASKUTTY under my supervision. No part of the thesis has been submitted for any degree before. Thiruvananthapuram DR. T. JAMAL MOHAMMED 07.09.2012 Supervising Teacher 2 K.V.THOMASKUTTY Principal St. Johns College, Anchal DECLARATION I, K. V. THOMASKUTTY, do hereby declare that this thesis entitled THE ANGLO INDIAN COMMUNITY IN KERALA has not previously formed the basis for the award of any degree, diploma, associateship, fellowship or other similar title or recognition Thiruvananthapuram K. V. THOMASKUTTY 07.09.2012 3 CONTENTS Pages PREFACE i - v LIST OF PLATES v CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1 - 7 CHAPTER II HISTORICAL EVOLUTION AND EXPANSION OF ANGLO-INDIAN COMMUNITY IN KERALA 8 - 37 CHAPTER III SOCIO-CULTURAL TRAITS, PATTERNS, LIFESTYLE AND ACHIEVEMENTS OF ANGLO-INDIANS IN INDIA 38 - 69 CHAPTER IV ANGLO-INDIANS OF KERALA, A CASE OF COCHIN SETTLEMENT 70- 94 CHAPTER V THE CHANGING STATUS OF THE ANGLO- INDIANS IN THE POST INDEPENDENT ERA- 95 - 128 A CONSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS CHAPTER VI THE PEAGEANTRY OF THE ANGLO-INDIAN INSTITUTIONS AND STRUGGLE FOR EXISTANCE 129-154 CHAPTER VII CONCLUSION 155-164 APPENDICES 165-197 GLOSSARY 198-200 BIBLIOGRAPHY 201 – 209 4 PREFACE The European domination in India lead to the evolving of a new biological hybrid ethnic group called the Eurasians later came to be known as Anglo-Indians. -

District:HEAD OFFICE, THIRUVANANTHAPURAM

District:HEAD OFFICE, THIRUVANANTHAPURAM ICE/ ICO/ Category Date of Date of ICO(R) / Name and & Capital Fee DD No & Date of Issue of No. Validity Application Registrtn/ Address Type of investment remitted Date enquiry clearance/ Authoristn/ industry Refusal Refusal Instrumentation 1 online CVO red 22.63 Cr 3 lakhs 03.11.2015 29.02.2016 30.06.2018 ltd Palakkad Muraliya 2 online CVO red 35 Cr 1 lakhs 21.07.2014 29.02.2016 31.05.2017s Products TVM Baby Memorial 3 online ICO-R red 94 Cr 360000 28.07.2015 17.02.2016 30.06.2018 hospital Ltd. KKD Mahindra Holidays & 4 online ICO-R Orange 23.87 Cr 180000 13.01.2016 02.03.2016 31.01.2019 Resorts India Ltd, Kollam Anjali Crusher 5 online ICO red 1-5 Cr 1.3 lakh 25.06.2015 08.02.2016 30.06.2018 Industries, TVM M/s.MARIA THERESA HOSPITAL, 6 online ICO-R RED 74,24,564/- 60000/- 07.12.2015 28.02.2016 30.06.2018 KUZHIKKATTSSE RY,THRISUR- 680697 M/s.PETRONET LNG LTD, 4502.75 11,056,60 7 online ICO-R PUTHUVYPPU ORANGE 09.02.2015 28.02.2016 31.03.2018 P.O.,ERNAKULAM- CRORES 0/- 682508 Assisi 8 online ICO-R Atonemment red 2.44 cr 70,000/- 19.12.2015 29.02.2016 28.02.2018 Hospital-Kollam Vivanta By Taj 9 online ICO-R Orange 93.2 cr 300000/- 19.01.2016 01.03.2016 28.02.2019 (Doodla) TVM Tamara Real 10 online CVO Estate Holdings Orange 8800 lakhs 1.6 lakhs 29.03.2014 01.03.2016 31.01.2017 and developers Kannamthanam 11 online ICO-R red 10 cr 210000 22.01.2016 29.02.2016 28.02.2019 & Co, TVM Travancore Blue 12 online ICO-R red 5.89 cr 210000 03.02.2016 02.03.2016 28.02.2019 metals-TVM OFFICE : RO - Thiruvananthapuram ICE/ ICO/ Date of Date of ICO(R) / Category & Capital Fee Issue of No.