The Anglo Indian Community in Kerala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

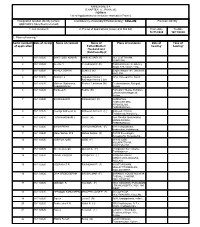

(CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for Inclusion

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): KOLLAM Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 16/11/2020 16/11/2020 3. Place of hearing * Serial number$ Date of receipt Name of claimant Name of Place of residence Date of Time of of application Father/Mother/ hearing* hearing* Husband and (Relationship)# 1 16/11/2020 SANTHOSH KUMAR MANI ACHARI (F) 163, CHITTAYAM, PANAYAM, , 2 16/11/2020 Geethu Y Yesodharan N (F) Padickal Rohini, Residency Nagar 129, Kollam East, , 3 16/11/2020 AKHILA GOPAN SUMA S (M) Sagara Nagar-161, Uliyakovil, KOLLAM, , 4 16/11/2020 Akshay r s Rajeswari Amma L 1655, Kureepuzha, kollam, , Rajeswari Amma L (M) 5 16/11/2020 Mahesh Vijayamma Reshmi S krishnan (W) Devanandanam, Mangad, Gopalakrishnan Kollam, , 6 16/11/2020 Sandeep S Rekha (M) Pothedath Thekke Kettidam, Lekshamana Nagar 29, Kollam, , 7 16/11/2020 SIVADASAN R RAGHAVAN (F) KANDATHIL THIRUVATHIRA, PRAKKULAM, THRIKKARUVA, , 8 16/11/2020 Neeraja Satheesh G Satheesh Kumar K (F) Satheesh Bhavan, Thrikkaruva, Kanjavely, , 9 16/11/2020 LATHIKAKUMARI J SHAJI (H) 184/ THARA BHAVANAM, MANALIKKADA, THRIKKARUVA, , 10 16/11/2020 SHIVA PRIYA JAYACHANDRAN (F) 6/113 valiyazhikam, thekkecheri, thrikkaruva, , 11 16/11/2020 Manu Sankar M S Mohan Sankar (F) 7/2199 Sreerangam, Kureepuzha, Kureepuzha, , 12 16/11/2020 JOSHILA JOSE JOSE (F) 21/832 JOSE VILLAKATTUVIA, -

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with Financial Assistance from the World Bank

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT (KSWMP) INTRODUCTION AND STRATEGIC ENVIROMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE Public Disclosure Authorized MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA VOLUME I JUNE 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by SUCHITWA MISSION Public Disclosure Authorized GOVERNMENT OF KERALA Contents 1 This is the STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK for the KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with financial assistance from the World Bank. This is hereby disclosed for comments/suggestions of the public/stakeholders. Send your comments/suggestions to SUCHITWA MISSION, Swaraj Bhavan, Base Floor (-1), Nanthancodu, Kowdiar, Thiruvananthapuram-695003, Kerala, India or email: [email protected] Contents 2 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE PROJECT .................................................. 1 1.1 Program Description ................................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Proposed Project Components ..................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Environmental Characteristics of the Project Location............................... 2 1.2 Need for an Environmental Management Framework ........................... 3 1.3 Overview of the Environmental Assessment and Framework ............. 3 1.3.1 Purpose of the SEA and ESMF ...................................................................... 3 1.3.2 The ESMF process ........................................................................................ -

KERALA September 2009

KERALA September 2009 1 KERALA September 2009 Investment climate of a state is determined by a mix of factors • Skilled and cost-effective labour • Procedures for entry and exit of firms • Labour market flexibility • Industrial regulation, labour regulation, • Labour relations other government regulations • Availability of raw materials and natural • Certainty about rules and regulations resources • Security, law and order situation Regulatory framework Resources/Inputs Investment climate of a state Incentives to industry Physical and social infrastructure • Tax incentives and exemptions • Condition of physical infrastructure such as • Investment subsidies and other incentives power, water, roads, etc. • Availability of finance at cost-effective terms • Information infrastructure such as telecom, • Incentives for foreign direct investment IT, etc. (FDI) • Social infrastructure such as educational • Profitability of the industry and medical facilities 2 KERALA September 2009 The focus of this presentation is to discuss… Kerala‘s performance on key socio-economic indicators Availability of social and physical infrastructure in the state Policy framework and investment approval mechanism Cost of doing business in Kerala Key industries and players 3 PERFORMANCE ON KEY SOCIO-ECONOMIC INDICATORS Kerala September 2009 Kerala‘s economic performance is driven by the secondary and tertiary sectors Kerala‘s GSDP (US$ billion) • Kerala‘s GDP grew at a CAGR of 13.5 per cent between 1999-00 and 2007-08 to reach US$ 40.4 billion. • The secondary sector has been the fastest growing sector, at a CAGR of 14.5 per cent, driven by manufacturing, construction, electricity, gas and water. • The tertiary sector, the largest contributor to Kerala‘s economy, grew at a rate of 12.5 per cent in 2007-08 over the previous year; it was driven by trade, hotels, real estate, transport and Percentage distribution of GSDP CAGR communications. -

Payment Locations - Muthoot

Payment Locations - Muthoot District Region Br.Code Branch Name Branch Address Branch Town Name Postel Code Branch Contact Number Royale Arcade Building, Kochalummoodu, ALLEPPEY KOZHENCHERY 4365 Kochalummoodu Mavelikkara 690570 +91-479-2358277 Kallimel P.O, Mavelikkara, Alappuzha District S. Devi building, kizhakkenada, puliyoor p.o, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 4180 PULIYOOR chenganur, alappuzha dist, pin – 689510, CHENGANUR 689510 0479-2464433 kerala Kizhakkethalekal Building, Opp.Malankkara CHENGANNUR - ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 3777 Catholic Church, Mc Road,Chengannur, CHENGANNUR - HOSPITAL ROAD 689121 0479-2457077 HOSPITAL ROAD Alleppey Dist, Pin Code - 689121 Muthoot Finance Ltd, Akeril Puthenparambil ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2672 MELPADAM MELPADAM 689627 479-2318545 Building ;Melpadam;Pincode- 689627 Kochumadam Building,Near Ksrtc Bus Stand, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2219 MAVELIKARA KSRTC MAVELIKARA KSRTC 689101 0469-2342656 Mavelikara-6890101 Thattarethu Buldg,Karakkad P.O,Chengannur, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1837 KARAKKAD KARAKKAD 689504 0479-2422687 Pin-689504 Kalluvilayil Bulg, Ennakkad P.O Alleppy,Pin- ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1481 ENNAKKAD ENNAKKAD 689624 0479-2466886 689624 Himagiri Complex,Kallumala,Thekke Junction, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1228 KALLUMALA KALLUMALA 690101 0479-2344449 Mavelikkara-690101 CHERUKOLE Anugraha Complex, Near Subhananda ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 846 CHERUKOLE MAVELIKARA 690104 04793295897 MAVELIKARA Ashramam, Cherukole,Mavelikara, 690104 Oondamparampil O V Chacko Memorial ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 668 THIRUVANVANDOOR THIRUVANVANDOOR 689109 0479-2429349 -

Hospital Master

S.No HOSPITALNAME STREET CITYDESC STATEDESC PINCODE 1 Highway Hospital Dev Ashish Jeen Hath Naka, Maarathon Circle Mumbai and Maharashtra 400601 Suburb 2 PADMAVATI MATERNITY AND 215/216- Oswal Oronote, 2nd Thane Maharashtra 401105 NURSING HOME 3 Jai Kamal Eye Hospital Opp Sandhu Colony G.T.Road, Chheharta, Amritsar Amritsar Punjab 143001 4 APOLLO SPECIALITY HOSPITAL Chennai By-Pass Road, Tiruchy TamilNadu 620010 5 Khanna Hospital C2/396,Janakpuri New Delhi Delhi 110058 6 B.M Gupta Nursing Home H-11-15 Arya Samaj Road,Uttam Nagar New Delhi Delhi 110059 Pvt.Ltd. 7 Divakar Global Hospital No. 220, Second Phase, J.P.Nagar, Bengaluru Karnataka 560078 8 Anmay Eye Hospital - Dr Off. C.G. Road , Nr. President Hotel,Opp. Mahalya Ahmedabad Gujarat 380009 Raminder Singh Building, Navrangpura 9 Tilak Hospital Near Ramlila Ground,Gurgaon Road,Pataudi,Gurgaon-Gurugram Haryana 122503 122503 10 GLOBAL 5 Health Care F-2, D-2, Sector9, Main Road, Vashi, Navi Mumbai Mumbai and Maharashtra 400703 Suburb 11 S B Eye Care Hospital Anmol Nagar, Old Tanda Road, Tanda By-Pass, Hoshiarpur Punjab 146001 Hoshiarpur 12 Dhir Eye Hospital Old Court Road Rajpura Punjab 140401 13 Bilal Hospital Icu Ryal Garden,A wing,Nr.Shimla Thane Maharashtra 401201 Park,Kausa,Mumbra,Thane 14 Renuka Eye Institute 25/3,Jessre road,Dakbanglow Kolkata West Bengal 700127 More,Rathala,Barsat,Kolkatta 15 Pardi Hospital Nh No-8, Killa Pardi, Opp. Renbasera HotelPardi Valsad Gujarat 396001 16 Jagat Hospital Raibaraily Road, Naka Chungi, Faizabad Faizabad Uttar Pradesh 224001 17 SANT DNYANESHWAR Sant Nagar, Plot no-1/1, Sec No-4, Moshi Pune Maharashtra 412105 HOSPITAL PRIVATE LIMITED Pradhikaran,Pune-Nashik Highway, Spine Road 18 Lotus Hospital #389/3, Prem Nagar, Mata Road-122001 Gurugram Haryana 122001 19 Samyak Hospital BM-7 East Shalimar Bagh New Delhi Delhi 110088 20 Bristlecone Hospitals Pvt. -

Abstract of the Agenda for the Meeting of Rta,Ernakulam Proposed to Be Held on 20-05-2014 at Conference Hall,National Savings Hall,5Th Floor, Civil Station,Ernakulam

ABSTRACT OF THE AGENDA FOR THE MEETING OF RTA,ERNAKULAM PROPOSED TO BE HELD ON 20-05-2014 AT CONFERENCE HALL,NATIONAL SAVINGS HALL,5TH FLOOR, CIVIL STATION,ERNAKULAM Item No.01 G/21147/2014/E Agenda: To consider the application for fresh intra district regular permit in respect ofstage carriage KL-15-4449 to operate on the route Gothuruth-Aluva via Vadakkumpuram,Paravur and U.C College as ordinary service. Applicant:The Managing Director,KSRTC,Tvm Proposed Timings Aluva Paravur Gothuruth A D A D A D 05.15 5.30 6.45 5.45 7.00 8.00 9.10 8.10 9.40 10.25 10.35 11.20 11.30 12.30 1.00 12.45 2.15 1.30 2.25 3.25 4.50 3.50 5.00 6.00 7.25(Halt) 6.10 Item No.02 G/21150/2014/E Agenda: To consider the application for fresh intra district regular permit in respect of stage carriage KL-15-4377 to operate on the route Gothuruth-Aluva via Vadakkumpuram,Paravur and U.C College as ordinary service. Applicant:The Managing Director,KSRTC,Tvm Proposed Timings Aluva Paravur Gothuruth A D A D A D 6.45 7.00 8.10 7.10 8.20 9.20 10.50 9.50 11.00 11.45 12.00 12.45 12.55 1.10 2.10 2.25 3.35 2.35 4.00 5.00 6.10 5.10 6.20 7.05H Item No.03 G/21143/2014/E Agenda: To consider the application for fresh intra district regular permit in respect of stage carriage KL-15-5108 to operate on the route Gothuruth-Aluva via Vadakkumpuram,Paravur and U.C College as ordinary service. -

The Madras Presidency, with Mysore, Coorg and the Associated States

: TheMADRAS PRESIDENG 'ff^^^^I^t p WithMysore, CooRGAND the Associated States byB. THURSTON -...—.— .^ — finr i Tin- PROVINCIAL GEOGRAPHIES Of IN QJofttell HttinerHitg Blibracg CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION CHINA AND THE CHINESE THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 1918 Digitized by Microsoft® Cornell University Library DS 485.M27T54 The Madras presidencypresidenc; with MysorMysore, Coor iliiiiliiiiiiilii 3 1924 021 471 002 Digitized by Microsoft® This book was digitized by Microsoft Corporation in cooperation witli Cornell University Libraries, 2007. You may use and print this copy in limited quantity for your personal purposes, but may not distribute or provide access to it (or modified or partial versions of it) for revenue-generating or other commercial purposes. Digitized by Microsoft® Provincial Geographies of India General Editor Sir T. H. HOLLAND, K.C.LE., D.Sc, F.R.S. THE MADRAS PRESIDENCY WITH MYSORE, COORG AND THE ASSOCIATED STATES Digitized by Microsoft® CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS HonBnn: FETTER LANE, E.G. C. F. CLAY, Man^gek (EBiniurBi) : loo, PRINCES STREET Berlin: A. ASHER AND CO. Ji-tipjifl: F. A. BROCKHAUS i^cto Sotfe: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS iBomlaj sriB Calcutta: MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd. All rights reserved Digitized by Microsoft® THE MADRAS PRESIDENCY WITH MYSORE, COORG AND THE ASSOCIATED STATES BY EDGAR THURSTON, CLE. SOMETIME SUPERINTENDENT OF THE MADRAS GOVERNMENT MUSEUM Cambridge : at the University Press 1913 Digitized by Microsoft® ffiambttige: PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A. AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS. Digitized by Microsoft® EDITOR'S PREFACE "HE casual visitor to India, who limits his observations I of the country to the all-too-short cool season, is so impressed by the contrast between Indian life and that with which he has been previously acquainted that he seldom realises the great local diversity of language and ethnology. -

Thesis Plan V2.Indd

Building with Nature To balance the urban growth of coastal Kochi with its ecological structure P2 Report | January 2013 Delta Interventions Studio | Department of Urbanism Faculty of Architecture |Delft University of Technology Author: Jiya Benni First Mentor: Anne Loes Nillesen Second Mentor: Saskia de Wit Delta Interventions Colophon Jiya Benni, 4180321 M.Sc 3 Urbanism, Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands email: [email protected] phone: +31637170336 17 January 2013 Contents 1. Introduction 5. Theoretical Framework 1.1 Estuaries and Barrier Islands 5.1 Building with Nature (BwN) 1.2 Urban growth 5.2 New Urbanism + Delta Urbanism 1.3 Ecological Structure 5.3 Landscape Architecture 5.4 Coastal Zone Management and Integrated Coastal Zone 2. Defi ning the Problem Statement Management 2.1Project Location 2.1.1 History 6. Methodology 2.1.2 Geography 6.1 Literature Review 2.1.3 Demographics 6.2 Site Study 2.1.4 City Structure 6.3 Workshops and Lectures 2.1.5 Morphological Evolution 6.4 Modelling 2.1.6 Importance of the City 6.5 Consultation with Experts 2.2 At the Local Scale 2.2.1 Elankunnapuzha: Past,Preset and Future 7. Societal and Scientifi c Relevance 2.2.2 Elankunnapuzha as a Sub-centre 7.1 What is New? 2.3 Problem Defi nition 7.1.1 Integrating different variables 2.3.1 Background 7.1.2 Geographical Boundaries v/s Political Boundaries 2.3.1.1 New Developments 7.2 Societal Relevance 2.3.1.2 Coastal Issues 7.3 Scientifi c Relevance 2.3.1.3 Ecological Issues 2.3.1.4 Climate Change 8. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Ernakulam City District from 18.11.2018To24.11.2018

Accused Persons arrested in Ernakulam City district from 18.11.2018to24.11.2018 Name of Name of Name of the Place at Date & Arresting the Court Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, at which No. Accused Sex Sec of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 CC 13/817,Fathima Cr.1605/18 21, Seelattu 18.11.2018 Dineshkumar SI JFCM 1 Nissam Ashraf House Karuvelipady U/s 27 NDPS Mattanchery Male Parambu 11.35 Hrs of Police Mattanchery Thoppumpady Act Cr.1611/18, 65, CC 5/46 Bazar Road Near Cochin 19.11.2018 PeterPrakash, JFCM 2 Shamsu Ebrahim U/S 15(c) Abkari Mattanchery Male Mattanchery college 16.05 Hrs S I of Police Mattanchery Act Cr.1615/18 PeterPrakash, CC 5/327 Valiya 20.11.2018 JFCM 3 Sulaiman Abdulla 70, Male Chakkamadam U/s 15(c) Mattanchery S I of Parambu Mattanchery 17.05 Hrs Mattanchery Abkari Act Police Cr.1617/18 PeterPrakash, CC 5/532 Opp Azraj EVM Theatre 21.11.2018 JFCM 4 Shifas Ali 20, Male U/s 27 NDPS Mattanchery S I of Building Mattanchery Compound 09.25 Hrs Mattanchery Act Police CC 4/1577 hasan Cr.1623/18 PeterPrakash, 22.11.2018 JFCM 5 Ansem Ansar 22, Male Colony Cheralai Kada Ajantha Theatre U/s 27 NDPS Mattanchery S I of 10.20 Hrs Mattanchery Mattanchery Act Police CC 3/621 Mangalathu Cr.1627/18 Dineshkumar, Parambil House 22.11.2018 JFCM 6 Nuhas Navas Navas M M 18, Male Koovapadam U/s 27 NDPS Mattanchery S I of Musliyarakam MASS 21.15 Hrs Mattanchery Police Road Mattanchery Act Cr.1631/18 Dineshkumar, CC 6/1483 -

BENJOY C JOY | Dr. Sheeja K P Participatory Regionalism Leading to Sustainable City Design- a Case of Urban Water Metro, Kochi

BENJOY C JOY | Dr. Sheeja K P Participatory Regionalism leading to Sustainable City Design- a case of Urban Water Metro, Kochi Sustainable development through participatory regionalism a case of emerging integrated water transport network of Kochi. Regions are tied to each other by road, rail and water transportation networks. Every region has an identity by collective consciousness. When regions are made accessible they become hot spots of conservation. Kochi is an estuarine city. The arrival of the Kochi water metro service brings hopes to the islanders of the Kochi city region. Kadamakudy panchayat and Cheranellur panchayat are two such panchayats having a set of ten islands. This set of ten islands share a common history, religion, festivals and traditions. The islands Valiya Kadamakudy, Cheria Kadamakudy, Kothad, Moolampilly, Chariyam thuruthu, Pizhala, Murickal, Pulikkappuram and Chennur form the Kadamakudy panchayat. The islands South Chittoor and Koren kottai along with Cheranellur constitute the Cheranellur panchayat. These islands were initially occupied by fishermen, farmers and potters mainly from the Latin Christian and Luso Indians community. Chittoor palace constructed by the erstwhile king of Cochin royal family was the summer palace. The king travelled from the hill palace a.k.a the winter palace to the summer palace in boat. This shows how water transportation was a crucial component in those days. Then schools and hospitals were built on these islands thereby adding more housing stock to this place. Due to the Coastal Regulation Zone restrictions and Kerala land utilization order preventing reclamation of wetlands no new developments are happening on these islands. Kettukalakkal festival is the harvest festival of Kadamakudy panchayat. -

Kerala Sustainable Urban Development Project

Government of Kerala Local Self Government Department Kerala Sustainable Urban Development Project (PPTA 4106 – IND) FINAL REPORT VOLUME 2 - CITY REPORT KOCHI MAY 2005 COPYRIGHT: The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of ADB & Government of Kerala. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of either ADB or Government of Kerala constitutes an infringement of copyright. TA 4106 –IND: Kerala Sustainable Urban Development Project Project Preparation FINAL REPORT VOLUME 2 – CITY REPORT KOCHI Contents 1. BACKGROUND AND SCOPE 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Project Goal and Objectives 1 1.3 Study Outputs 1 1.4 Scope of the Report 1 2. CITY CONTEXT 2 2.1 Geography and Climate 2 2.2 Population Trends and Urbanization 2 2.3 Economic Development 2 2.3.1 Sectoral Growth 2 2.3.2 Industrial Development 6 2.3.3 Tourism Growth and Potential 6 2.3.4 Growth Trends and Projections 7 3. SOCIO-ECONOMIC PROFILE 8 3.1 Introduction 8 3.2 Household Profile 8 3.2.1 Employment 9 3.2.2 Income and Expenditure 9 3.2.3 Land and Housing 10 3.2.4 Social Capital 10 3.2.5 Health 10 3.2.6 Education 11 3.3 Access to Services 11 3.3.1 Water Supply 11 3.3.2 Sanitation 11 3.3.3 Urban Drainage 12 3.3.4 Solid Waste Disposal 12 3.3.5 Roads, Street Lighting & Access to Public Transport 12 4. POVERTY AND VULNERABILITY 13 4.1 Overview 13 4.1.1 Employment 14 4.1.2 Financial Capital 14 4.1.3 Poverty Alleviation in Kochi 14 5. -

PROTECTED AREA UPDATE News and Information from Protected Areas in India and South Asia

PROTECTED AREA UPDATE News and Information from protected areas in India and South Asia Vol. XVII No. 3 June 2011 (No. 91) LIST OF CONTENTS Maharashtra 11 EDITORIAL 3 Forest union threatens to shut down tiger reserves The business of reports High Court not against windmills in and around NEWS FROM INDIAN STATES Koyna WLS Assam 4 Reshuffle at the top of the Maharashtra FD Train-elephant collision averted in Deepor Beel Naxals trying to make inroads into Tadoba Commercial fishing threat to Missamari beel Andhari Tiger Reserve Genetic assessment of tigers at Manas TR Corridor adjoining Tadoba Andhari TR threatened Three forest staff killed in animal attacks in by Gosikhurd Canal project Kaziranga NP since January Joint meeting to discuss conservation of Great Gujarat 5 Indian Bustard Sanctuary First satellite tagging of Whale shark in Gujarat Orissa 13 Mobile van to deal with human-animal conflicts More than 3.5 lakh turtles nest at Gahirmatha in around Gir February – March, 2011 Maldharis petition government opposing their Rajasthan 14 relocation from Gir Clearance to five major projects in and around Haryana 7 protected areas Master-plan for Sultanpur NP CEC orders stoppage of construction work inside Jammu & Kashmir 8 Ranthambhore TR Two day workshop on ‘Practicing Responsible Rajasthan Government announces Amrita Devi Tourism’ Vishnoi Smriti Puraskar Jharkhand 8 Forest Training Centre at Jaipur MoEF issues draft notification for Dalma Eco- Tamil Nadu 15 Sensitive Zone Field Learning Centre at KMTR Karnataka 8 Fear of forest fires results in closure of Petitioner seeks stay on Banerghatta night safari in Mudumalai TR in April; mixed reactions Supreme Court Uttarakhand 16 Public hearing held to declare Konchavaram Rs.