NOT RECOMMENDED for FULL-TEXT PUBLICATION File Name: 18A0441n.06

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ARMY LAWYER Headquarters, Department of the Army

THE ARMY LAWYER Headquarters, Department of the Army February 2012 ARTICLES Rethinking Voir Dire Lieutenant Colonel Eric R. Carpenter Follow the Money: Obtaining and Using Financial Informati on in Military Criminal Investi gati ons and Prosecuti ons Major Scott A. McDonald Infl uencing the Center of Gravity in Counterinsurgency Operati ons: Conti ngency Leasing in Afghanistan Major Michael C. Evans TJAGLCS FEATURES Lore of the Corps The Trial by Military Commission of “Mother Jones” BOOK REVIEWS Lincoln and the Court Reviewed by Captain Brett A. Farmer Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief Reviewed by Major Luke Tillman CLE NEWS CURRENT MATERIALS OF INTERESTS Department of the Army Pamphlet 27-50-465 Editor, Captain Joseph D. Wilkinson II Technical Editor, Charles J. Strong The Army Lawyer (ISSN 0364-1287, USPS 490-330) is published monthly The Judge Advocate General’s School, U.S. Army. The Army Lawyer by The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School, Charlottesville, welcomes articles from all military and civilian authors on topics of interest to Virginia, for the official use of Army lawyers in the performance of their military lawyers. Articles should be submitted via electronic mail to legal responsibilities. Individual paid subscriptions to The Army Lawyer are [email protected]. Articles should follow The available for $45.00 each ($63.00 foreign) per year, periodical postage paid at Bluebook, A Uniform System of Citation (19th ed. 2010) and the Military Charlottesville, Virginia, and additional mailing offices (see subscription form Citation Guide (TJAGLCS, 16th ed. 2011). No compensation can be paid for on the inside back cover). -

V. Vera - Monroig , 204 F.3D 1 (1St Cir

I N THE U NITED S TATES C OURT OF A PPEALS F OR THE F IRST C IRCUIT _____________________________ Case No. 16 - 1186 _____________________________ V LADEK F ILLER , P LAINTIFF - A PPELLEE v . M ARY K ELLETT , D EFENDANT - A PPELLANT H ANCOCK C OUNTY ; W ILLIAM C LARK ; W ASHINGTON C OUNTY ; D ONNIE S MITH ; T RAVIS W ILLEY ; D AVID D ENBOW ; M ICHAEL C RABTREE ; T OWN OF G OULDSBORO , ME; T OWN OF E LLSWORTH , ME; J OHN D ELEO ; C HAD W ILMOT ; P AUL C AVANAUGH ; S TEPHEN M C F ARLAND ; M ICHAEL P OVICH ; C ARLETTA B ASSANO ; E STATE OF G UY W YCOFF ; L INDA G LEASON D EFENDANTS ___________________________________ B RIEF OF A MICI C URIAE A MERICAN C IVIL L IBERTIES U NION A MERICAN C IVIL L IBERTIES U NION OF M AINE F OUNDATION M AINE A SSOCIATION OF C RIMINAL D EFENSE L AWYERS I N SUPPORT OF P LAINTIFF - A PPELLEE F ILLER _____________________________________ Rory A. McNamara Ezekiel Edwards Jamesa J. Drake* #1158903 #1176027 American Civil Counsel of Record Drake Law, LLC Liberties Union Zachary L. Heiden #99242 P.O. B ox 811 125 Broad Street, American Civil Liberties Berwick, ME 03901 18 th Floor Union of Maine Foundation (207) 475 - 7810 New York, NY 121 Middle Street, Ste. 301 on behalf of Maine Assoc. of (212) 549 - 2500 Portland, ME 04101 Criminal Defense Lawyers (207) 774 - 5444 on behalf of ACLU and ACLU - Maine CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT Neither the American Civil Liberties Union, the American Civil Liberties Union of Maine Foundation, n or the Maine Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers has a parent corporation, and no publicly held corporation owns any stake in any of these organizations. -

STATE of TENNESSEE V. LLOYD CRAWFORD

07/15/2021 IN THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEALS OF TENNESSEE AT JACKSON February 3, 2021 Session STATE OF TENNESSEE v. LLOYD CRAWFORD Appeal from the Criminal Court for Shelby County No. 17-02526 Chris Craft, Judge ___________________________________ No. W2019-02056-CCA-R3-CD ___________________________________ The Defendant-Appellant, Lloyd Crawford, was convicted by a Shelby County Criminal Court jury of first-degree felony murder, attempted first-degree murder, employing a firearm during the commission of a dangerous felony, attempted especially aggravated robbery, and tampering with evidence. See Tenn. Code Ann. §§ 39-13-202 (first-degree murder), 39-12-101 (criminal attempt), 39-17-1324 (employing a firearm), 39-13-403 (especially aggravated robbery), 39-16-503 (tampering with evidence). The trial court imposed a total effective sentence of life plus seventeen years. On appeal, the Defendant asserts that the evidence is insufficient to sustain his convictions. After review, we affirm the judgments of the trial court. Tenn. R. App. P. 3 Appeal as of Right; Judgments of the Criminal Court Affirmed CAMILLE R. MCMULLEN, J., delivered the opinion of the court, in which D. KELLY THOMAS, JR., and J. ROSS DYER, JJ., joined. Eric J. Montierth, Memphis, Tennessee, for the Defendant-Appellant, Lloyd Crawford. Herbert H. Slatery III, Attorney General and Reporter; Ronald H. Coleman, Assistant Attorney General; Amy P. Weirich, District Attorney General; and Jose F. Leon and Melanie Cox, Assistant District Attorneys General, for the Appellee, State of Tennessee. OPINION This case arises from an incident on December 31, 2016, when the Defendant, his codefendant, Andrew Ellis, and a third man, Muwani Dewberry, attempted to rob and subsequently murder the victim, Keith Crum. -

Suppression of Exculpatory Evidence

TEXAS CRIMINAL JUSTICE INTEGRITY UNIT AUSTIN, TEXAS OCTOBER 5, 2012 SUPPRESSION OF EXCULPATORY EVIDENCE Paper and Presentation by: Gary A. Udashen Sorrels, Udashen & Anton 2311 Cedar Springs Road, Suite 250 Dallas, Texas 75201 214-468-8100 214-468-8104 fax [email protected] www.sualaw.com GARY A. UDASHEN Sorrels, Udashen & Anton 2311 Cedar Springs Road Suite 250 Dallas, Texas 75201 www.sualaw.com 214-468-8100 Fax: 214-468-8104 [email protected] www.sualaw.com BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION EDUCATION B.S. with Honors, The University of Texas at Austin, 1977 J.D., Southern Methodist University, 1980 PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES Innocence Project of Texas, President; State Bar of Texas (Member, Criminal Law Section, Appellate Section); Dallas Bar Association, Chairman Criminal Section; Fellow, Dallas Bar Association; Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association, Board Member, Chairman, Appellate Committee, Legal Specialization Committee, Co- Chairman, Strike Force; National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers; Dallas County Criminal Defense Lawyers Association; Dallas Inn of Courts, LVI; Board Certified, Criminal Law and Criminal Appellate Law, Texas Board of Legal Specialization; Instructor, Trial Tactics, S.M.U. School of Law, 1992, Texas Criminal Justice Integrity Unit, Member; Texas Board of Legal Specialization, Advisory Committee, Criminal Appellate Law LAW RELATED PUBLICATIONS, ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS AND HONORS: Features Article Editor, Voice for the Defense, 1993-2000 Author/Speaker: Advanced Criminal Law Course, 1989, 1994, 1995, 2003, 2006, 2009, 2010 Author/Speaker: Criminal Defense Lawyers Project Seminars, Dallas Bar Association Seminars, Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Seminars, Center for American and International Law Seminars, 1988-2011 Author: Various articles in Voice for the Defense, 1987-2005 Author: S.M.U. -

Transitional Justice Observatory Nº 11 - November 2013

Transitional Justice Observatory Nº 11 - November 2013 International Criminal Court (ICC) ICC: UNSG urges ratification of the Rome Statute At the opening of the 12th Session of the Assembly of States Parties of the International Criminal Court (ICC), UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon urged member states to ratify the Rome Statute. Ban said that the Rome Statute must be universally accepted to be fully effective, but 43 countries have neither signed nor agreed to it yet and 31 have yet to ratify it. Other challenges faced by the organisation include delivering decisions and justice without undue delay, overcoming the lack of necessary resources and staffing shortages, dispensing justice impartially and in accordance with international human rights law and standards and being perceived as doing the same (UN, 20/11/13; Jurist, 21/11/13). LIBYA: ICC prosecutor encourages Libya to establish a comprehensive strategy that goes farther than its agreement with the Court International Criminal Court (ICC) Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda declared before the UNSC that her office has signed an agreement with Libya to share tasks to prosecute the suspected perpetrators of crimes committed in Libya since 15 February 2011. Thanks to this agreement, the ICC will mainly focus on suspects outside Libya, while Libyan judicial authorities will focus on those within the country. While Libya’s engagement with the ICC and the draft law that would make rape during armed conflict a war crime in Libya are steps in the right direction, some challenges remain, such as torture, the killing of detainees and tensions regarding the Tawergha minority. -

Samuel White Horse.Pdf

Case 3:20-cr-30058-RAL Document 193 Filed 06/24/21 Page 1 of 29 PageID #: 704 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF SOUTH DAKOTA CENTRAL DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, 3:20-CR-30058-RAL Plaintiff, FINAL JURY INSTRUCTIONS vs. SAMUEL FRANCIS WHITE HORSE, Defendant. Case 3:20-cr-30058-RAL Document 193 Filed 06/24/21 Page 2 of 29 PageID #: 705 INSTRUCTION NO. 1 Members of the jury, the instructions I gave you at the beginning of the trial and during the trial remain in effect. I now give you some additional instructions. The instructions I am about to give you now are in writing and will be available to you in the jury room. You must, of course, continue to follow the instructions I gave you earlier, as well as those I give you now. You must not single out some instructions and ignore others, because all are important. All instructions, whenever given and whether in writing or not, must be followed. Case 3:20-cr-30058-RAL Document 193 Filed 06/24/21 Page 3 of 29 PageID #: 706 INSTRUCTION NO. 2 It is your duty to find from the evidence what the facts are. You will then apply the law, as I give it to you, to those facts. You must follow my instructions on the law, even if you thought the law was different or should be different. Do not allow sympathy or prejudice to influence you. The law demands of you a just verdict, unaffected by anything except the evidence, your common sense, and the law as I give it to you. -

Evidence Destroyed, Innocence Lost: the Preservation of Biological Evidence Under Innocence Protection Statutes

American University Washington College of Law Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals Scholarship & Research 2005 Evidence Destroyed, Innocence Lost: The Preservation of Biological Evidence under Innocence Protection Statutes Cynthia Jones American University Washington College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Evidence Commons, and the Fourteenth Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Cynthia, "Evidence Destroyed, Innocence Lost: The Preservation of Biological Evidence under Innocence Protection Statutes" (2005). Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals. 1636. https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev/1636 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarship & Research at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVIDENCE DESTROYED, INNOCENCE LOST: THE PRESERVATION OF BIOLOGICAL EVIDENCE UNDER INNOCENCE PROTECTION STATUTES Cynthia E. Jones* In 1997, Texas governor George W. Bush issued a pardon to Kevin Byrd, a man convicted of sexually assaulting a pregnant woman while her two-year old daughter lay asleep beside her.' As part of the original criminal investigation, a medical examination was performed on the victim and bodily fluids from the rapist were collected for forensic analysis in a "rape kit." At the time of Mr. Byrd's trial in 1985, DNA technology was not yet available for forensic analysis of biological evidence.2 In 1997, however, a comparison of Mr. -

STATE of TENNESSEE V. TORIJON COPLIN

07/26/2021 IN THE COURT OF CRIMINAL APPEALS OF TENNESSEE AT JACKSON December 4, 2020 Session STATE OF TENNESSEE v. TORIJON COPLIN Appeal from the Circuit Court for Madison County No. 19-83 Roy B. Morgan, Jr., Judge ___________________________________ No. W2019-01593-CCA-R3-CD ___________________________________ A jury convicted the Defendant, Torijon Coplin, of aggravated assault and tampering with evidence, and he received an effective sentence of four years suspended to supervised probation after eleven months and twenty-nine days of service. On appeal, the Defendant challenges the sufficiency of the evidence supporting his convictions and argues the trial court erred in charging the jury as to criminal responsibility. Because the criminal responsibility charge did not include the natural and probable consequences requirement and because the error was not harmless beyond a reasonable doubt as to the tampering with evidence conviction, we reverse the conviction for tampering with evidence and remand for further proceedings. The judgments are otherwise affirmed. Tenn. R. App. P. 3 Appeal as of Right; Judgments of the Circuit Court Affirmed in Part; Reversed in Part; Case Remanded JOHN EVERETT WILLIAMS, P.J., delivered the opinion of the court, in which CAMILLE R. MCMULLEN J., joined. J. ROSS DYER, J., filed a separate opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part Jeremy Epperson (at trial), District Public Defender; and Brennan M. Wingerter (on appeal), Assistant Public Defender – Appellate Division, for the appellant, Torijon Coplin. Herbert H. Slatery III, Attorney General and Reporter; Ronald L. Coleman, Assistant Attorney General; Jody Pickens, District Attorney General; and Lee R. -

![State V. Jones, 2019-Ohio-5237.] COURT of APPEALS of OHIO](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1427/state-v-jones-2019-ohio-5237-court-of-appeals-of-ohio-1751427.webp)

State V. Jones, 2019-Ohio-5237.] COURT of APPEALS of OHIO

[Cite as State v. Jones, 2019-Ohio-5237.] COURT OF APPEALS OF OHIO EIGHTH APPELLATE DISTRICT COUNTY OF CUYAHOGA STATE OF OHIO, : Plaintiff-Appellee, : No. 108050 v. : GREGGORY JONES, : Defendant-Appellant. : JOURNAL ENTRY AND OPINION JUDGMENT: AFFIRMED IN PART; VACATED IN PART RELEASED AND JOURNALIZED: December 19, 2019 Criminal Appeal from the Cuyahoga County Court of Common Pleas Case No. CR-17-617001-A Appearances: Michael C. O’Malley, Cuyahoga County Prosecuting Attorney, and Brian D. Kraft, Assistant Prosecuting Attorney, for appellee. Britt Newman, for appellant. MICHELLE J. SHEEHAN, J.: Greggory Jones appeals from his convictions of felonious assault and tampering with evidence and the firearm specifications accompanying tampering with evidence. He also challenges the maximum term he received for tampering with evidence. On appeal, he raises the following assignments of error for our review: 1. Appellant’s conviction for felonious assault was not based on sufficient evidence and was against the manifest weight of the evidence. 2. Appellant’s conviction for tampering with evidence was not based on sufficient evidence and was against the manifest weight of the evidence. 3. The trial court erred in sentencing appellant to serve a three-year firearm specification attached to the tampering with evidence charge due to the state’s failure to prove the elements of the specification. 4. The trial court erred in sentencing appellant to serve a one-year firearm specification attached to the tampering with evidence charge since the alleged tampering rendered the firearm inoperable. 5. The trial court erred when it sentenced appellant to consecutive firearm specifications in violation of his constitutional protection against cruel and unusual punishment in violation of his right to substantive due process. -

Outline Descendant Report for Thomas Marvel Jr

Outline Descendant Report for Thomas Marvel Jr. 1 Thomas Marvel Jr. b: 11 Nov 1732 in Stepney Parish, Somerset County, Maryland, d: 15 Dec 1801 in Dover, Kent County, Delaware + Susannah Rodney b: 1742 in Sussex County, Delaware, m: Sussex County, Delaware, d: 1797 in Sussex County, Delaware ...2 Thomas Marvel III b: 08 Mar 1761, d: 1801 + Nancy Knowles b: 1765 in Sussex County, Delaware, d: 1820 in Sussex County, Delaware ......3 James W. Marvel b: 1780 in Sussex County, Delaware, d: 13 Dec 1840 in Concord, Sussex, Delaware + Margaret Marvel b: 1781 in Broad Creek Hundred, Sussex, Delaware, m: 1808 in Sussex County, Delaware, d: 1850 in Seaford, Sussex County, Delaware .........4 Caldwell Windsor Marvel b: 21 Aug 1809, d: 15 Nov 1848 in Seaford, Sussex County, Delaware + Elizabeth Lynch b: 10 Apr 1807 in Sussex County, Delaware, m: 05 Jul 1837 in Sussex County, Delaware, d: 10 Mar 1869 in Sussex County, Delaware ............5 William Thomas Marvel b: 12 Aug 1838 in Millsboro, Sussex, Delaware, d: 21 Jan 1914 in Lewes, Sussex County, Delaware + Mary Julia Carpenter b: 1842 in Delaware, m: 08 Sep 1861, d: 1880 ...............6 Ida F. Marvel b: Aug 1868 in Delaware + Frank J. Jones b: Feb 1867 in Virginia, m: 1891 ..................7 Anna W Jones b: Feb 1892 in Delaware ..................7 William A Jones b: Nov 1894 in Delaware ..................7 Alverta W Jones b: Dec 1898 in Delaware ..................7 James F Jones b: 1901 in Delaware ...............6 Charles H. Marvel b: 1873 in Delaware ...............6 William Thomas Marvel Jr. b: 22 Nov 1875 in Wilmington, Delaware, d: 17 Aug 1956 in Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Age: 81 + Mary G Laubmeister b: Feb 1881 in Germany, m: 1900 in New Jersey ..................7 Margaret E Marvel b: 1902 in New Jersey, USA ..................7 Edward W Marvel b: 31 Oct 1904 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, d: 02 Jul 1963 in Cheltenham, Montgomery, Pennsylvania; Age: 58 + Mary G McMenamin b: Abt. -

Descendants of John Lathey

Descendants of John Lathey Prepared by: Thomas N. Oatney Table of Contents Descendants of John Lathey 1 First Generation 1 Second Generation 1 Third Generation 1 Fourth Generation 4 Fifth Generation 15 Sixth Generation 39 Seventh Generation 73 Eighth Generation 98 Ninth Generation 110 Tenth Generation 118 Name Index 120 Produced by: Thomas Oatney tom @ oatney . org : 24 Mar 2021 Descendants of John Lathey First Generation 1. John Lathey was born about 1750 in Ulster, Northern Ireland and died before Mar 1810 in Fauquier County, VA. John married Susannah Burton on an unknown date. Susannah was born in 1783 in Fauquier County, VA and died in 1853 in Athens County, OH at age 70. Children from this marriage were: + 2 M i. William Lathey was born about 1783 in Fauquier County, VA, died in May 1826 in Athens County, OH about age 43, and was buried in Pageville Cemetery, Pageville, Meigs County, OH. 3 F ii. Betsy Lathey was born about 1785 in Fauquier County, VA and died on an unknown date. Betsy married John Sudduth on 8 Mar 1806 in Fauquier County, VA. John was born about 1785 in Fauquier County, VA and died on an unknown date. Second Generation (Children) 2. William Lathey (John 1) was born about 1783 in Fauquier County, VA, died in May 1826 in Athens County, OH about age 43, and was buried in Pageville Cemetery, Pageville, Meigs County, OH. William married Elizabeth "Betsy" Hudnall, daughter of Thomas Hudnall and Mary Ann Strickler, on 13 Jan 1806 in Fauquier County, VA. Elizabeth was born about 1783 in Fauquier County, VA, died on 15 Feb 1853 in Athens County, OH about age 70, and was buried in Pageville Cemetery, Pageville, Meigs County, OH. -

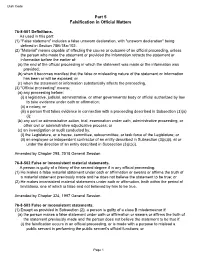

Part 5 Falsification in Official Matters

Utah Code Part 5 Falsification in Official Matters 76-8-501 Definitions. As used in this part: (1) "False statement" includes a false unsworn declaration, with "unsworn declaration" being defined in Section 78B-18a-102. (2) "Material" means capable of affecting the course or outcome of an official proceeding, unless the person who made the statement or provided the information retracts the statement or information before the earlier of: (a) the end of the official proceeding in which the statement was made or the information was provided; (b) when it becomes manifest that the false or misleading nature of the statement or information has been or will be exposed; or (c) when the statement or information substantially affects the proceeding. (3) "Official proceeding" means: (a) any proceeding before: (i) a legislative, judicial, administrative, or other governmental body or official authorized by law to take evidence under oath or affirmation; (ii) a notary; or (iii) a person that takes evidence in connection with a proceeding described in Subsection (3)(a) (i); (b) any civil or administrative action, trial, examination under oath, administrative proceeding, or other civil or administrative adjudicative process; or (c) an investigation or audit conducted by: (i) the Legislature, or a house, committee, subcommittee, or task force of the Legislature; or (ii) an employee or independent contractor of an entity described in Subsection (3)(c)(i), at or under the direction of an entity described in Subsection (3)(c)(i). Amended by Chapter 298, 2018 General Session 76-8-502 False or inconsistent material statements. A person is guilty of a felony of the second degree if in any official proceeding: (1) He makes a false material statement under oath or affirmation or swears or affirms the truth of a material statement previously made and he does not believe the statement to be true; or (2) He makes inconsistent material statements under oath or affirmation, both within the period of limitations, one of which is false and not believed by him to be true.