The Role of Ip Protection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DENVER CAPITAL MATRIX Funding Sources for Entrepreneurs and Small Business

DENVER CAPITAL MATRIX Funding sources for entrepreneurs and small business. Introduction The Denver Office of Economic Development is pleased to release this fifth annual edition of the Denver Capital Matrix. This publication is designed as a tool to assist business owners and entrepreneurs with discovering the myriad of capital sources in and around the Mile High City. As a strategic initiative of the Denver Office of Economic Development’s JumpStart strategic plan, the Denver Capital Matrix provides a comprehensive directory of financing Definitions sources, from traditional bank lending, to venture capital firms, private Venture Capital – Venture capital is capital provided by investors to small businesses and start-up firms that demonstrate possible high- equity firms, angel investors, mezzanine sources and more. growth opportunities. Venture capital investments have a potential for considerable loss or profit and are generally designated for new and Small businesses provide the greatest opportunity for job creation speculative enterprises that seek to generate a return through a potential today. Yet, a lack of needed financing often prevents businesses from initial public offering or sale of the company. implementing expansion plans and adding payroll. Through this updated resource, we’re striving to help connect businesses to start-up Angel Investor – An angel investor is a high net worth individual active in and expansion capital so that they can thrive in Denver. venture financing, typically participating at an early stage of growth. Private Equity – Private equity is an individual or consortium of investors and funds that make investments directly into private companies or initiate buyouts of public companies. Private equity is ownership in private companies that is not listed or traded on public exchanges. -

Corporate Venturing Report 2019

Corporate Venturing 2019 Report SUMMIT@RSM All Rights Reserved. Copyright © 2019. Created by Joshua Eckblad, Academic Researcher at TiSEM in The Netherlands. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS LEAD AUTHORS 03 Forewords Joshua G. Eckblad 06 All Investors In External Startups [email protected] 21 Corporate VC Investors https://www.corporateventuringresearch.org/ 38 Accelerator Investors CentER PhD Candidate, Department of Management 43 2018 Global Startup Fundraising Survey (Our Results) Tilburg School of Economics and Management (TiSEM) Tilburg University, The Netherlands 56 2019 Global Startup Fundraising Survey (Please Distribute) Dr. Tobias Gutmann [email protected] https://www.corporateventuringresearch.org/ LEGAL DISCLAIMER Post-Doctoral Researcher Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche AG Chair of Strategic Management and Digital Entrepreneurship The information contained herein is for the prospects of specific companies. While HHL Leipzig Graduate School of Management, Germany general guidance on matters of interest, and every attempt has been made to ensure that intended for the personal use of the reader the information contained in this report has only. The analyses and conclusions are been obtained and arranged with due care, Christian Lindener based on publicly available information, Wayra is not responsible for any Pitchbook, CBInsights and information inaccuracies, errors or omissions contained [email protected] provided in the course of recent surveys in or relating to, this information. No Managing Director with a sample of startups and corporate information herein may be replicated Wayra Germany firms. without prior consent by Wayra. Wayra Germany GmbH (“Wayra”) accepts no Wayra Germany GmbH liability for any actions taken as response Kaufingerstraße 15 hereto. -

Venture Capital Communities

Abstract Venture Capital Communities Syndicates account for two-thirds of the capital invested by venture capital firms. Through syndications, venture capitalists form several non-exclusive, partially overlapping partner- ships with other VC firms. We study the structure of these inter-VC alliances. We show that the repeated partnerships leads to agglomeration of VC firms into “communities” or soft- border conglomerates whose members are probabilistically more likely to partner with each other than with outsiders. We characterize the number and composition of communities and their economic e↵ects. Communities exhibit subtle composition e↵ects with heterogeneity on the dimensions of size, influence, and geography but homogeneity in industry and stage focus. These e↵ects are consistent with resource complementarity theories of organizational boundaries as well as theories in which syndicate members rely on and value each other for evaluation, screening, and risk-sharing. Community membership is associated with positive economic outcomes for portfolio firms. Firms sourcing capital from community VCs are more likely to exit and do so sooner. Our results are consistent with models in which VCs learn by doing and the e↵ectiveness of learning depends on the nature of a VC’s syndicate partners. Key words Venture Capital, Syndication, Community Detection, Social Interactions JEL classification G20, G24 1 Introduction Venture capital (VC) firms are financial intermediaries that provide capital to young en- trepreneurial firms. They raise capital from wealthy individuals or institutional investors such as pension funds and university endowments to invest in young and risky ventures with high upside. The VC industry has grown significantly since the first limited partnership was formed in 1958. -

3Q 2019 Contents Credits & Contact

Global League Tables 3Q 2019 Contents Credits & contact PitchBook Data, Inc. Introduction 2 John Gabbert Founder, CEO Adley Bowden Vice President, PE firms 3-11 Market Development & Analysis Content VC firms 12-19 Garrett James Black Senior Advisors/accountants & investment banks 20-25 Manager, Custom Research & Publishing Law firms: VC & PE 26-35 Van Le Senior Data Analyst Acquirers 36-38 Contact PitchBook Research [email protected] Cover design by Kelilah King Click here for PitchBook’s report methodologies. Introduction Thank you to all who participated in the surveys that firm for each given section), however, spacing and enable these rankings to be possible. Once again, near- aggregate tallies prevented us from adopting that cutoff record submissions led to this edition of the Global consistently on every page. All in all, we are confident League Tables being released somewhat later in the that the current tables will provide a useful, accurate quarter. As always at PitchBook, we prioritize accuracy snapshot of activity throughout 3Q 2019 by our array of above all else. We will continue to elect to provide the typical criteria, from venture transactions by stage to US most precise information over speed until we are sure we region. can accomplish both. Stay tuned for potential changes to these rankings as In this edition, we carried over our style of rankings, we continue to look for the most efficient and accurate which should prove helpful for quick consultation. We way to showcase the most active firms across private endeavored to keep the number of rankings equivalent markets. per page (e.g. -

1Q 2019 Relationship Management Purpose-Built for Finance Learn More at Affinity.Co

Co-sponsored by Global League Tables 1Q 2019 Relationship Management Purpose-Built for Finance Learn more at affinity.co IMPROVE ELIMINATE SUPPORT DISCOVER PROPIERTARY CROSSING YOUR NEW EXECUTIVE DEAL FLOW WIRES PORTFOLIO CONNECTIONS Learn why 500+ firms use Affinity's patented technology to leverage their network and increase deal flow “Within weeks of moving “The biggest problems Affinity “Let’s be honest, no one wants to Affinity, we were able to helps me solve are how to to use Salesforce reporting. easily discover and manage track all of my activity and how Affinity isn’t just better for most the 1,000s of entrepreneur to prioritize my time. It makes teams, it’ll make the difference and venture community me a better investor. All of the between managing your relationships already latent things I need to do on a day-to- pipeline to success, versus not within our team." day basis I now do in Affinity.” tracking it at all.” ERIC EMMONS KYLE LUI KEVIN ZHANG Managing Director Partner Principal MassMutual Ventures DCM Ventures Bain Capital Ventures [email protected]@affinity.co AffinityAffinity is a relationship is a relationship intelligence intelligence platform platform built to builtexpand to expandand evolve and theevolve traditional the traditional CRM. AffinityCRM. Affinityinstantly instantly surfaces surfaces all all www.affinity.cowww.affinity.co of yourof team’s your team’sdata to data show to you show who you is bestwho issuited best tosuited make to the make crucial the crucialintroductions introductions you need you to need close to your close next your big next deal. big deal. -

Adams Street

Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea Pension Fund June 30, 2019 Quarterly Report Confidential Quarterly Report-Q2'19 Table of Contents Market Update 2 Summary 5 Diversification 6 Partnership Fund Program Executive Summary 9 Performance and Portfolio Highlights 10 Detailed Schedule of Investments 18 Notes and Footnotes 32 Adams Street Partners has provided this report (the “Report”) to the recipient on a confidential basis for purposes of monitoring the recipient’s Adams Street Partners investments. This Report contains highly confidential information, including trade secret information, that is proprietary to Adams Street Partners and/or underlying funds and/or portfolio investments. In accepting the Report, the recipient agrees that it will (i) not copy, reproduce or distribute the Report, in whole or in part, to any person or party (including any employee of the recipient other than an employee or other representative directly involved in evaluating the recipient’s investments with, or monitored by, Adams Street Partners) without the prior written consent of Adams Street Partners, (ii) keep permanently confidential all information not already public contained herein, and (iii) use the Report solely for the purpose set forth above. Numbers in this report are based on Adams Street Partners’ calculations and have not been reviewed or approved by the relevant general partners. Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea Pension Fund 1 Confidential Quarterly Report-Q2'19 Market Update During the three months ended June 30, most equity markets globally continued to process should also be able to verify and validate controls in place that can mitigate a surge, resulting in a six-month performance start to the year that fully offset the weak operational environment. -

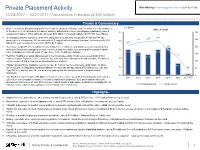

Private Placement Activity Chris Hastings | [email protected] | 917-621-3750 10/23/2017 – 10/27/2017 (Transactions in Excess of $20 Million)

Private Placement Activity Chris Hastings | [email protected] | 917-621-3750 10/23/2017 – 10/27/2017 (Transactions in excess of $20 million) Trends & Commentary $ in Billions . Market saturation, disappointing public floats and the duopoly of Google and Facebook have all contributed Adtech Deals to the decline in VC interest in the adtech industry; adtech deal volume has dropped significantly since it 2.5 300 reached 241 deals in 2014, and has only seen $0.1 billion in invested capital in 2017 YTD. (see figure) . In contrast to adtech, edtech is on the rise, partly due to its ability to incorporate AI, AR and VR into 235 241 227 250 products for the classroom. VC investment in U.S.-based edtech startups is on pace to reach nearly $1.4 2.0 billion this year, a sharp increase from 2016’s $1.0 billion. 207 . Revelstoke Capital Partners, which invests mainly in the healthcare and business services sectors, has 180 200 hired Eric Shuey as a managing director. Prior to joining Revelstoke, Eric worked at Fresenius Medical 1.5 $1.6 Care, bringing more than 25 years of experience in the health care industry. $1.5 $1.5 150 $1.3 121 . Petrichor Healthcare Capital Management is the first private equity firm to receive seed funding from $1.2 Archean Capital Partners, a joint-venture between Moelis Asset Management and Veritable. Petrichor is 1.0 set to receive a $100 million anchor investment from Archean. 100 . Pritzker Group Private Capital is seeking to raise $1.5 billion for its next private equity fund. -

Pitchbook's Annual Global League Tables

Global League Tables 2019 Annual 1 PITCHBOOK 2019 ANNUAL GLOBAL LEAGUE TABLES Contents Credits & Contact PitchBook Data, Inc. Introduction 2 John Gabbert Founder, CEO Adley Bowden Vice President, PE firms 3-11 Market Development & Analysis VC firms 12-19 Content Garrett James Black Senior Advisors/accountants & investment banks 20-25 Manager, Custom Research & Publishing Law firms: VC & PE 26-35 Aria Nikkhoui Data Analyst II Keenan Durham Dataset Team Lead Acquirers 36-38 Kylie Hannus Senior Research Associate Kunal Rai Senior Research Associate Madison Bond Senior Research Associate Johnny Starcevich Research Associate Contact PitchBook Research [email protected] Cover design by Kelilah King Click here for PitchBook’s report methodologies. Introduction For the inaugural edition of Global League Tables in 2020, Once again, thanks to all the survey participants that we are doing something new. In addition to the usual collaborate with our teams; all the mutual hard work rankings provided here, we hope to release an interactive enables more accurate representation of overall private table in the coming weeks, which will hopefully present a markets activity. more user-friendly, immersive experience and avoid any spatial constraints. Garrett James Black However, the customary array of rankings can still be Senior Manager, Custom Research expected, from the breakdown of the most active private & Publishing equity firms by US region to the law firms that advise on the most M&A transactions worldwide. 2 PITCHBOOK 2019 ANNUAL GLOBAL LEAGUE -

Private Placement Activity Chris Hastings | [email protected] | 917-621-3750 3/19/2018 – 3/23/2018 (Transactions in Excess of $20 Million)

Private Capital Group Private Placement Activity Chris Hastings | [email protected] | 917-621-3750 3/19/2018 – 3/23/2018 (Transactions in excess of $20 million) Trends & Commentary ▪ This week, 15 U.S. private placement deals between $20 million and $50 million closed, accounting for $452 million in total proceeds, compared to last week’s 13 U.S. deals leading to $421 million in total U.S. Corporate VC Activity $ in Billions proceeds. This week also had 6 U.S. deals between $50 million and $100 million yielding $365 million, $50 compared to last week’s 5 deals resulting in $341 million in total proceeds. 1,379 ▪ U.S. corporate venture capital deal volume has grown over the past decade from $10.0 billion in 2008 to $45 1,283 1,268 $37.4 billion in 2017. The number of deals has increased as well, from 674 in 2008 to 1,268 in 2017. (see 1,231 $40 figure) ▪ Dropbox priced its IPO at $21 per share and traded up 40% on its opening to close at $28.48 a share. The $35 1,045 Company raised $756 million and had an initial market cap of more than $8.0 billion. Dropbox previously raised $350 million in Series C funding at a $9.7 billion pre-money valuation from BlackRock in 2014. $30 829 713 ▪ Zscaler, a provider of a global cloud security platform, priced its IPO last week at $27.50 per share, raising $25 674 $192 million. The Company had originally planned to sell 10 million shares between $10 and $12 a share. -

Start-Up Space Report 2020

Start-Up Space Update on Investment in Commercial Space Ventures 2020 i Bryce Space and Technology brycetech.com CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................... III INTRODUCTION. 1 Purpose and Background . 1 Methodology ...................................................1 OVERVIEW OF START-UP SPACE VENTURES. 3 TYPES OF SPACE INVESTOR ......................................4 SPACE INVESTMENT BY THE NUMBERS ...........................11 Seed Funding . 15 Venture Capital . 16 Private Equity . 17 Acquisition ...................................................18 Public Offering ................................................19 Debt Financing . 19 Investment Across All Types .....................................19 Valuation ....................................................21 Casualties ...................................................22 SPACE INVESTORS BY THE NUMBERS ............................23 Overall ......................................................23 Angels ......................................................27 Venture Capital Firms . 28 Private Equity Groups ..........................................31 Corporations . 32 Banks and Other Financial Institutions .............................33 SPECIAL TOPIC: CHINESE ACTIVITY IN START-UP SPACE VENTURES. 35 START-UP SPACE: WHAT’S NEXT?. 38 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. 41 ii brycetech.com Bryce Space and Technology EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Three significant trends are shaping the start-up space environment as we enter the 2020s. First, investors continue to pour large amounts -

2014 Preqin Private Equity Performance Monitor Sample Pages.Indd

Executive Summary - Sample Pages The 2014 Preqin Private Equity Performance Monitor Fig. 1.1: All Private Equity - Assets Under Management, 2000 - 2013 4,000 1. Executive Summary 3,500 1,174 3,000 941 Dry Powder 2,500 1,007 ($bn) Record Highs Furthermore, and perhaps most notably 993 for investors, performance data shows that 2,000 1,067 1,011 In last year’s Preqin Private Equity distributions have increased considerably Unrealized 1,500 1,075 Performance Monitor, we acknowledged over the past year, from $381bn in 2012 to 2,546 Portfolio Value 806 2,332 the economic turmoil that was endured by $568bn in 2013, making it the highest level ($bn) 1,000 563 2,029 the industry following the crash of 2008, of capital LPs have ever received back from 1,783 402 409 298 377 407 1,265 1,413 the onset of the European sovereign debt their private equity investments in a year. 500 898 1,204 Assets under Management ($bn) 675 crisis, and the fl uctuations around these Fig. 1.2 displays the new peak, and more 418 374 360 465 554 events. All-in-all, the progress of the private trends in private equity dry powder and 0 equity market since the downturn six years AUM are discussed in Chapter 11. ago has been encouraging, refl ected in the ever increasing amounts of capital investors Risk and Return Dec-00 Dec-01 Dec-02 Dec-03 Dec-04 Dec-05 Dec-06 Dec-07 Dec-08 Dec-09 Dec-10 Dec-11 Dec-12 Dec-13 around the world commit to the asset class. -

Insurance Technology Four Trillion Dollar Industry Finally Goes Digital

Insurance Technology Four Trillion Dollar Industry Finally Goes Digital Greg Roth, Partner Ben Howe, CEO Matei Sanders, Principal Catch the Wave . Insurance Technology is riding a wave of innovation and investment that is attempting to do in a few short years what the insurance industry itself has failed to do over the last decade: a complete digital migration across all business processes . With $4.6 Trillion in global annual premiums, or 5.6% of global GDP, the insurance industry is a highly attractive market where incumbents have been slow to embrace innovation . There are three competitive threats at work in the insurance market and they all point to Technology Disruption: (1) an explosion of well funded, InsureTech startups; (2) the feared entry of the B2C tech “titans” (i.e. Google, Amazon, Facebook, etc.); and (3) incumbents racing to adopt modern enabling technologies . Investors can sense the opportunity: InsureTech investments are up six-fold over the last five years across at all stages of funding . Whereas this first wave has primarily focused on distribution, a second wave is taking aim at how insurance products are designed, priced, and operated . Incumbents’ initial reaction has been to partner and invest mostly in enabling technology . These market forces point to increased M&A activity as customer demand will make InsureTech solutions key to an insurer’s customer acquisition and retention strategy (# of Private Insurance Tech Investments Ramping Placements) 200 173 150 122 100 91 63 46 50 28 0 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Source: Capital IQ, CB Insights 2 Investment in Technology Pays Dividends Investment in Technology Translates to .