The Theatre of Protest in Kerala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

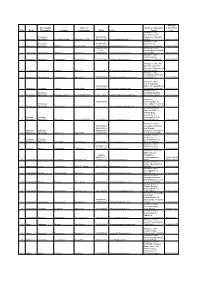

Accused Persons Arrested in Kottayam District from 08.09.2019To14.09.2019

Accused Persons arrested in Kottayam district from 08.09.2019to14.09.2019 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Palambadam Cr:1152/19 U/s Mundakayam 08.09.19 Shibukumar V , 1 Eappen Abraham 64 House,Kalathilpadi 15 © r/w 63 of Mundakayam Station Bail Byepass 12.40 Hrs IP SHO Jn,Vijayapuram Village Abkari Act Arangattu House, Cr:1152/19 U/s Near Hospital, Mundakayam 08.09.19 Shibukumar V , 2 Jacob James 52 15 © r/w 63 of Mundakayam Station Bail Collectrate P O, Byepass 12.40 Hrs IP SHO Abkari Act Muttambalam Vaniyapurackal Cr:1153/19 U/s Mundakayam 08.09.19 Shibukumar V , 3 Anil Mathew Mathew 52 House,Changanasseri 15 © r/w 63 of Mundakayam Station Bail Byepass 13.05 Hrs IP SHO P O,Changanasseri Abkari Act Cr:1153/19 U/s Kunnukattu Mundakayam 08.09.19 Shibukumar V , 4 Joy Saimon 69 15 © r/w 63 of Mundakayam Station Bail House,Changanassery Byepass 13.05 Hrs IP SHO Abkari Act Mathichiparambil Cr:1153/19 U/s Mundakayam 08.09.19 Shibukumar V , 5 Mathew John 59 House,, Chethippuzha, 15 © r/w 63 of Mundakayam Station Bail Byepass 13.05 Hrs IP SHO Cheeranchira Abkari Act Padiyara Cr:1153/19 U/s House,vazhappally Mundakayam 08.09.19 Shibukumar V , 6 JoJo Padiyara Joseph 49 15 © r/w 63 of Mundakayam Station Bail East Bhagom, Byepass 13.05 Hrs IP SHO Abkari Act Changanasseri Puthupparambil Cr:1157/19 U/s 08.09.19 KJ Mammmen, 7 Biju P Soman Soman 31 House, Thalunkal P O, Mundakayam 118(a) of KP Mundakayam Station Bail 20.35 Hrs GSI Koottickal Act Puthenplackal Cr:1158/19 U/s House,Vallakadu 08.09.19 KJ Mammmen, 8 Jeevan Binoy Thomas 45 Mundakayam 279 IPC & 185 Mundakayam Station Bail bhagom,Yendayar, 23.30 Hrs GSI MV Act Koottickal Poothakuzhiyil House,Punchavayal P Cr: 1163/19 JFMC Satheesh 10.09.19 KJ Mammmen, 9 Chellappan 39 O,504 Colony, 504 Colony U/s 55(A)1 of Mundakayam KANJIRAPPALL Kumar 16.35 Hrs GSI Ayyankaly Jn. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kottayam District from 06.12.2020To12.12.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Kottayam district from 06.12.2020to12.12.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 THANNIMOOTTIL HOUSE, KODIKUTHI SANKARAN REMANIKA Cr. No. 1402 West Police JFCM-III Court 1 VIJAYAN T S 41 & M KARA, KUNINJI, 12-12-2020 DILEEPKUMAR KUTTY JUNCTION U/s. 279 IPC Station Kottayam PURAPPUZHA, THODUPUZHA ANANTHANPARAMBIL HOUSE, KARAPPUZHA Cr. No. 1401 West Police JFCM-III Court 2 SUSEELAN KUNJAPPAN 58 & M MUKKANJIRAM SCHOOL 12-12-2020 SURESH T U/s. 279 IPC Station Kottayam BHAGOM, PAYIPPAD, BHAGOM KOTTAYAM KADAKKAMATTAM HOUSE, INFRONT OF MOHANA K S KANIYAMKULAM Cr. No. 1400 West Police JFCM-III Court 3 55 & M GENERAL 12-12-2020 SURESH T CHANDRA LAL NARAYANAN BHAGOM, U/s. 279 IPC Station Kottayam HOSPITAL ARPOOKKARA, KOTTAYAM PARUTHIKUZHI KARIKULANGA Cr. No. 1399 West Police JFCM-III Court 4 ACHU BABU BABUKUTTAN 23 & M HOUSE, S H MOUNT RA TEMPLE 12-12-2020 SURESH T U/s. 279 IPC Station Kottayam P.O, KOTTAYAM BHAGOM PALATHINKAL THOPPIL HOUSE, PATHINANCHIPADY PULIMOODU Cr. No. 1398 West Police JFCM-III Court 5 ROSHAN MON MANIKUTTAN 32 & M 12-12-2020 SURESH T BHAGOM, PAKKIL JUNCTION U/s. 283 IPC Station Kottayam KARA, NATTAKOM, KOTTAYAM OTTAKANDATHIL INFRONT OF Cr. -

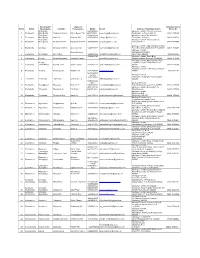

Sl.No. Block Panchayath/ Municipality Location Name of Entrepreneur Mobile E-Mail Address of Akshaya Centre Akshaya Centre Phone

Akshaya Panchayath/ Name of Address of Akshaya Centre Phone Sl.No. Block Municipality Location Entrepreneur Mobile E-mail Centre No Akshaya e centre, Chennadu Kavala, Erattupetta 9961985088, Erattupetta, Kottayam- 1 Erattupetta Municipality Chennadu Kavala Sajida Beevi. T.M 9447507691, [email protected] 686121 04822-275088 Akshaya e centre, Erattupetta 9446923406, Nadackal P O, 2 Erattupetta Municipality Hutha Jn. Shaheer PM 9847683049 [email protected] Erattupetta, Kottayam 04822-329714 9645104141 Akshaya E-Centre, Binu- Panackapplam,Plassnal 3 Erattupetta Thalappalam Pllasanal Beena C S 9605793000 [email protected] P O- 686579 04822-273323 Akshaya e-centre, Medical College, 4 Ettumanoor Arpookkara Panampalam Renjinimol P S 9961777515 [email protected] Arpookkara, Kottayam 0481-2594065 Akshaya e centre, Hill view Bldg.,Oppt. M G. University, Athirampuzha 5 Ettumanoor Athirampuzha Amalagiri Shibu K.V. 9446303157 [email protected] Kottayam-686562 0481-2730349 Akshaya e-centre, , Thavalkkuzhy,Ettumano 6 Ettumanoor Athirampuzha Thavalakuzhy Josemon T J 9947107199 [email protected] or P.O-686631 0418-2536494 Akshaya e-centre, Near Cherpumkal 9539086448 Bridge, Cherpumkal P O, 7 Ettumanoor Aymanam Valliyad Nisha Sham 9544670426 [email protected] Kumarakom, Kottayam 0481-2523340 Akshaya Centre, Ettumanoor Municipality Building, 8 Ettumanoor Muncipality Ettumanoor Town Reeba Maria Thomas 9447779242 [email protected] Ettumanoor-686631 0481-2535262 Akshaya e- 9605025039 Centre,Munduvelil Ettumanoor -

Central Administrative Tribunal, Ernakulam Bench

1 CENTRAL ADMINISTRATIVE TRIBUNAL, ERNAKULAM BENCH Review Application No. 180/00014/2018 in Original Application No. 180/00460/2015 Friday, this the 16th day of March, 2018 CORAM: Hon'ble Mr. U. Sarathchandran, Judicial Member Hon'ble Mr. E.K. Bharat Bhushan, Administrative Member 1. Union of India, represented by Secretary to Government of India, Ministry of Communications, New Delhi. 2. The Director (Staff), Department of Posts, Ministry of Communications & IT, New Delhi 110001. 3. The Chief Postmaster General, Kerala Circle, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala. 4. The Senior Superintendent of Post Offices, Kottayam Division, Kottayam, Kerala. ..... Review Applicants (By Advocate : Mr. K. Kesavankutty, ACGSC) V e r s u s 1. Beena Madhavan, wife of K.N.Sivadas, aged 51 years, Accountant, Kottayam Head Post Office, Kottayam, residing at Kalappurackal House, Kanakkari P.O., Kottayam 686632. 2. Mary A.C, wife of Joseph V.O., aged 52 years, Sub Postmaster, Arunapuram, Kottayam Division, residing at Arackathazathu House, Kidangoor P.O., Kottayam 686 572. 3. Babu Thomas, son of T.T.Thomas, aged 53 years, Sub Postmaster, Melukamattom, Kottayam Division, residing at Areeplackal, Peringulam, Kottayam 686 582. 4. K. Lethamol, wife of P.N.AshokBabu, aged 51 years, Postal Assistant, Ettamanoor, Kottayam, residing at Poothrayil House, Kurumulloor P.O., Kanakary 686632. 5. Elsamma George, wife of Mathew Joseph, aged 50 years, Sub Postmaster, Mannanam, Kottayam Division, residing at Vengachuvattil House, Athirampuzha P.O., Kottayam 686 562. 2 6. Anil A G, son of M.K.Gopalakrishnan Nair, aged 50 years, Sub Postmaster, Vadavathoor, Kottayam Division, residing at Sreemandiram, Koeroppade P.O., Kottayam 686 502. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kottayam District from 17.05.2020To23.05.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Kottayam district from 17.05.2020to23.05.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Cr. No. 646/20 ERUMANGALATH H, U/S MINI CIVIL 18.05.20 KOTTAYAM 1 PHILIP JOSEPH JOSEPH 62 KUMARANALLOOR 2336,269,188 SREEJITH T BAILED STATION 12:02 Hrs WEST PS PO, KOTTAYAM IPC & 4(2)(a) OF KEPDO Cr. No. 646/20 BHAGAVATHY U/S MUHAMMED PARAMBIL H, MINI CIVIL 18.05.20 KOTTAYAM 2 ABDUL KHADER 52 2336,269,188 SREEJITH T BAILED BASHEER KARAPPUZHA PO, STATION 12:02 Hrs WEST PS IPC & 4(2)(a) KOTTAYAM OF KEPDO Cr. No. 646/20 KALAALAYAM H, U/S UNNIKRISHNA MINI CIVIL 18.05.20 KOTTAYAM 3 BHASKARAN 58 PADINJAREMURY 2336,269,188 SREEJITH T BAILED N STATION 12:02 Hrs WEST PS BHAGOM, VAIKOM IPC & 4(2)(a) OF KEPDO Cr. No. 646/20 VILLATHARA H, U/S MINI CIVIL 18.05.20 KOTTAYAM 4 SASI GOPALAKRISHNAN 44 NAGAMBADOM, 2336,269,188 SREEJITH T BAILED STATION 12:02 Hrs WEST PS KOTTAYAM IPC & 4(2)(a) OF KEPDO Cr. No. 646/20 KOMALAPURAM H, U/S AVARMMA, MINI CIVIL 18.05.20 KOTTAYAM 5 SAJEEVAN RAKHAVAN NAIR 50 2336,269,188 SREEJITH T BAILED PERUMBADAVU, STATION 12:02 Hrs WEST PS IPC & 4(2)(a) KOTTAYAM OF KEPDO Cr. -

Sl.No. Block Location Mobile E-Mail Address of Akshaya Centre 1 Erattupetta Chennadu Kavala Sajida Beevi. T.M [email protected]

Panchayath/ Name of Akshaya Centre Sl.No. Block Municipality Location Entrepreneur Mobile E-mail Address of Akshaya Centre Phone No Erattupetta 9961985088, Akshaya e centre, Chennadu Kavala, 1 Erattupetta Municipality Chennadu Kavala Sajida Beevi. T.M 9447507691, [email protected] Erattupetta, Kottayam-686121 04822-275088 Erattupetta 9446923406, Akshaya e centre, Nadackal P O, 2 Erattupetta Municipality Hutha Jn. Shaheer PM 9847683049 [email protected] Erattupetta, Kottayam 04822-329714 Erattupetta Akshaya e centre, Thottumukku Jn., 3 Erattupetta Municipality Thottumukku Jn. Rasiya M Shereef 9847095886 [email protected] Erattupetta P O 04828-277550 Akshaya e centre, Opp. Melukavumattom 4 Erattupetta Melukavu Melukavu Mattom Anoop Mohan 9447515722 [email protected] Post office,Melukavumattom P O,686652 04822-220402 Akshaya e-centre, Minimol Antony Punnathaniyil Building 5 Erattupetta Moonnilavu Moonnilavu 9446861799 [email protected] Moonnilavu-686596 48222-86266 9745402710 Akshaya e centre, Chalil Bldg, 6 Erattupetta Poonjar Panachikkappara Aniamma Suresh [email protected] Panachikkapara, Poonjar P O-686581 04822-276506 Akshaya e centre, Panchayathu office Poonjar Complex,Poonjar Thekkekkara P O- 7 Erattupetta Thekkekkara Poonjar Town Shymol Jacob 9745402710 [email protected] 686582 04822-276506 Akshaya e centre, Panchayat Junction, Theekoy, Kottayam- 8 Erattupetta Teekkoy Panchayat Jn. Sulfath K H 9400233778 [email protected] 686581 48222-81145 9847093283 Suresh- Akshaya e-centre, 8547672267 Thalanadu, Thalanadu -

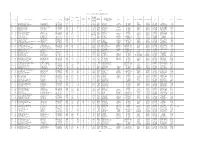

Sheet1 Page 1 LIST of SCHOOLS in KOTTAYAM DISTRICT 10 Sl. No

Sheet1 LIST OF SCHOOLS IN KOTTAYAM DISTRICT No of Students HS/HSS/ Year of VHSS/H Name of Panch- Std. Std. Boys/ 10 Sl. No. Name of School Address with Pincode Phone No Establishm SS ayat /Muncipality/ Block Taluk Name of Parliament Name of Assembly DEO AEO MGT Remarks (From) (To) Girls/ Mixed ent Boys Girls &VHSS/ Corporation TTI 10 1 Areeparambu Govt. HSS Areeparambu P.O. 0481-2700300 1905 42 36 I XII HSS Mixed Manarcadu Pallam Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Pampady Govt 10 2 Arpookara Medical College VHSS Gandhinagar P.O. 0481-2597401 1966 73 33 V XII HSS&VHSS Mixed Arpookara Ettumanoor Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Kottayam West Govt 10 3 Changanacherry Govt. HSS Changanacherry P.O. 0481-2420748 1871 43 23 V XII HSS Mixed Changanacherry ( M ) Changanacherry Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Changanassery Govt 10 4 Chengalam Govt. HSS Chengalam South P.O. 0481-2524828 1917 127 107 I XII HSS Mixed Thiruvarpu Pallam Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Kottayam West Govt 10 5 Karapuzha Govt. HSS Karapuzha P.O. 0481-2582936 1895 56 34 I XII HSS Mixed Kottayam( M ) Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Kottayam West Govt 10 6 Karipputhitta Govt. HS Arpookara P.O. 0481-2598612 1915 74 44 I X HS Mixed Arpookara Ettumanoor Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Kottayam West Govt 10 7 Kothala Govt. VHSS S.N. Puram P.O. 0481-2507726 1912 48 64 I XII VHSS Mixed Kooroppada Pampady Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Pampady Govt 10 8 Kottayam Govt. -

Minutes of the Meeting of the Rta, Kottayam Held on 26-02-2021 at Jilla Panchayath Hall, Kottayam

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE RTA, KOTTAYAM HELD ON 26-02-2021 AT JILLA PANCHAYATH HALL, KOTTAYAM ****************************************************************************** Item No. 1 J1/KL35J0678/2020/K ****************************************************************************** Heard the learned counsel represented for the applicant and representative of the KSRTC and objectors. This is an application for the grant fresh regular permit in respect of SC KL 35 J 0678/another suitable SC to operate on the route Kanjiramkavala – Pala via Pazhukkakanam, Illickalkallu, Mankombu Temple, Erattupetta and Bharananganam as Ordinary Service. This Authority considered the application and verified the connected documents and the enquiry report and all objections in detail. The portion of route from Maharani Junction to Kottaramattom BS (1.85 KMs) overlaps on Kottayam – Kattappana notified Scheme. The total distance of overlapping in the proposed route is 1.85 KM ie, 4.51 % of the total route length of 41 km and the same is under the permissible limit as per GO(P) No. 8/2017 Trans dated 23/03/2017. The enquiry officer reported that in the proposed portion of route from Kanjiramkavala to Pazhukkakkanam is ill served and granting a permit to this route is beneficial to public including students. Illickalkallu is a famous tourist place and it is beneficial to the tourists. At present there is no stage carriage service between Kalamukku and Pazhakkakkanam. With regard to the objections, the representative of the KSRTC pointed out that the major intermediate points between Erattupetta and Pala are not mentioned and therefore the exact route cannot be ascertained. There are objections against the proposed timings too. On verification of proposed timings, it is noted that more trips are offered between the well served sector between Pala and Erattupetta and less trips to the ill served sector. -

Kottayam District Disaster Management Plan

District Disaster Management Plan, 2015 Kottayam District Disaster Management Plan Published under Section 30 (2) (i) of the Disaster Management Act, 2005 (Central Act 53 of 2005) District Disaster Management Plan 2015 30th July 2016; Pages: 136 District This document is for official purposes only. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the District Disaster Management Authority to verify the information and ensure stakeholder consultation and inputs prior to publication of this document. The publisher welcomes suggestions for improved future editions. District Disaster Management Plan – KOTTAYAM 2015 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 VISION ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 1.2 MISSION ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 1.3 POLICY ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.4 OBJECTIVES OF THE PLAN ................................................................................................................................................ -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kottayam District from 14.06.2020To20.06.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Kottayam district from 14.06.2020to20.06.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 KALIYICKAL H, Cr. No. 719/20 ANANDHU UNNIKRISHAN THUKALASSERY NEAR POSR KOTTAYAM 1 20 14.06.20 U/S 279 IPC & SREEJITH T BAIL FROM PS KRISHANAN AN BHAGOM, OFFICE WEST PS 06:40 Hrs 132(1)/179 IPC THIRUVALLA KALARICKAL H, Cr. No. 720/20 KOTTAYAM 2 DEEPU VENUGOPAL 21 MOOLAVATTOM PO, STAR Jn. 14.06.20 U/S 279 IPC & SABU SUNNY BAIL FROM PS WEST PS NATTAKOM 10:30 Hrs 118(E) KP Act Cr. No. 721/20 THUMPAMALIYIL H, U/S KOTTAYAM 3 NIKHIL TR KOCHUMON 20 MOOLAVATTOM PO, AIDA Jn. 14.06.20 2336,269,291 SABU SUNNY BAIL FROM PS WEST PS NATTAKOM 11:00 Hrs IPC & 4(2)(a) OF KEPDO KIZHAKKENAKATHU H, Cr. No. 726/20 KOTTAYAM JFMC 1 4 JOJO JOYIN 23 MANARKADU , BAKER Jn. 15.06.20 U/S 20(B)ii(A) SUMESH T WEST PS KOTTAYAM KOTTAYAM 18:45 Hrs NDPS Act. KANAKKANIL H, Cr. No. 726/20 KOTTAYAM JFMC 1 5 JOMON KURIAKOSE 27 KALLUPURAYKAL H, BAKER Jn. 15.06.20 U/S 20(B)ii(A) SUMESH T WEST PS KOTTAYAM VELOOR 18:45 Hrs NDPS Act. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kottayam District from 23.05.2021To29.05.2021 Name of Name of Arresting Name of the Place at Date & the Court Sl

Accused Persons arrested in Kottayam district from 23.05.2021to29.05.2021 Name of Name of Arresting Name of the Place at Date & the Court Sl. Name of the Age & Address of Cr. No & Sec Police Officer, father of which Time of at which No. Accused Sex Accused of Law Station Rank & Accused Arrested Arrest accused Designatio produced n 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 HARIKRISHNAN MANOJ T K, HOUSE COLLECTORAT 24.05.2021, CR.1034/21,18 Kottayam SI OF POLI BAIL FROM 1 SUJITH SURENDRAN M-40 VETTATHUKAVALA E 08.40 HRS 8 IPC& KEDO east KOTTAYAM PS PUTHUPALLY EAST.P.S MANOJ T K, KOCHUKAITHAYIL CR 1035/21 RAMACHAND 24.05.2021, Kottayam SI OF POLI BAIL FROM 2 JAYAN M-59 HOUSE,PUTHUPALLY PUTHUPPALLY U/S 188 IPC& RAN 12.50 HRS east KOTTAYAM PS KOTTAYAM KEDO EAST.P.S KONDODICKEL CR 1036/21 ROOPESH 24.05.2021, Kottayam BAIL FROM 3 JAIMINI JOSE JOSE M-59 HOUSE KANJIKUZHY KANJIKUZHY U/S188IPC& K.R SI 13.30 HRS east PS KOTTAYAM KEDO KOTTAYAM BEJOY.P.T.IN PUTHUPARAMBIL CR 1037/21 SPECTOR OF AKHIL S HOUSE, 24.05.2021- Kottayam BAIL FROM 4 GEORGE M-39 PUTHUPPALLY U/S 188IPC& POLICE GEORGE KANJIRATHUMOOD 20.15 HRS east PS KEDO KOTTAYAM PUTHUPALLY EAST.P.S BINUMON.P. NEDUNGOTTUMALA CR 1040/21 C SI OF KRISHNANKUT COLLECTORAT 25.05.2021, Kottayam BAIL FROM 5 AKHIL M-31 HOUSE KUTTICKAL U/S 188 IPC& POLICE TY E 8.00 HRS east PS PAMPADY KEDO KOTTAYAM EAST.P.S BINUMON.P. -

Office of the Director of Higher Secondary Education Housing Board Buildings Santhinagar PO, Thiruvananthapuram

Office of the Director of Higher Secondary Education Housing Board Buildings Santhinagar PO, Thiruvananthapuram No. ICT Cell/ 01/26243//HSE/2008 6th September 2010 CIRCULAR Sub: Higher Secondary Education- ICT enabled Education- Training on ICT-enabled Tools- Kottayam Dt. -reg. Ref: Circular of even No. and dated 2nd January 2010 As part of the ICT in School Scheme projects for developing the ICT enabled education content also are fast progressing. The modules for different subjects are being developed jointly by the faculties in College and Higher Secondary Schools. Some ICT based initial modules in the subjects Physics, Chemistry and Mathematics are ready for training and dissemination. IT@School Project is the implementation agency of the ICT Scheme. Instructions in this regard were issued vide Circular referred to above. ICT-enabled training for the above subjects for Kottayam District is scheduled as shown below. There will be two batches for all the three subjects. There will be a Trainer Development Programme also preceding the field level training. Hence the Principals are directed to ensure that all the teachers who belong to the above subjects should attend the programmes without affecting the normal functioning of the school. All the participants shall bring Laptops for the training programme and if there is a shortage of laptops in Higher Secondary section the Principals shall make arrangements for sharing the Laptops of High School section. The Principals are directed to depute teachers for the training programmes detailed below. Sd/- DIRECTOR Copy to: 1 Executive Director, IT@School Project. 2 Joint Directors(Acad/Exam) 3 All Regional Deputy Directors 4 Principals of the concerned Higher Secondary Schools 5 Stock file/ File copy ICT ENABLED TRAINING 2010 KOTTAYAM RP TRAINING 8'TH, 9'TH SEPTEMBER 2010 SUBJECT: PHYSICS NAME OF TRG CENTRE MCVHSS ARPOOKKARA LIST OF PARTICIPANTS 1.