The Occupation of Small Islands by Passerine Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Summary of Changes to Endangered, Threatened, And

2015 Update to State Listed Species The Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) is required to review, at least every five years, the designation of species as endangered, threatened, or of special concern to determine whether species should be: (1) added or removed from the list; or, if necessary, (2) change the designation from one category to another. The following is a summary of the changes to the State Endangered Species list (DEEP Regulations Sections 26‐306‐4, 26‐306‐5, and 26‐306‐6) that became effective on August 5, 2015. The complete list can be found on the DEEP website. Summary of Amphibian Changes New species added Necturus maculosus, Mudpuppy added as Special Concern Summary of Reptile Changes New species added Clemmys guttata, Spotted turtle added as Special Concern Malaclemys terrapin terrapin, Northern diamondback terrapin added as Special Concern Taxonomic Changes Eumeces fasciatus, Five‐lined skink changed to Plestiodon fasciatus Liochlorophis vernalis, Smooth green snake changed to Opheodrys vernalis Summary of Bird Changes Northern diamondback terrapin Status Changes Falco sparverius, American kestrel downlisted to Special Concern Progne subis, Purple martin downlisted to Special Concern Sturnella magna, Eastern meadowlark uplisted to Threatened New species added Accipiter gentilis, Northern goshawk added as Threatened Setophaga cerulea, Cerulean warbler added as Special Concern Species delisted Anas discors, Blue‐winged teal Laterallus jamaicensis, Black rail Cerulean warbler Taxonomic changes Parula americana, Northern parula changed to Setophaga americana 1 Summary of Mammal Changes Status Changes Myotis leibii, Eastern small‐footed bat uplisted to Endangered New Species Added Myotis lucifugus, Little brown bat added as Endangered Myotis septentrionalis, Northern long‐eared bat added as Endangered (also Federally Threatened) Perimyotis subflavus, Tri‐colored bat added as Endangered Taxonomic Changes Phocoena phocoena, Harbor porpoise changed to Phocoena Northern long‐eared bat phocoena ssp. -

A Review of the Behavior and Ecology of the Northern Parula (Parula Americana) with Notes from Oklahoma and Texas

33 A Review of the Behavior and Ecology of the Northern Parula (Parula americana) With Notes From Oklahoma and Texas Michael D. Bay Department of Biology, East Central University, Ada, Oklahoma 74820 INTRODUCTION The Northern Parula (Parula americana) is one of several migratory wood warbler species (Family Parulidae) that breeds throughout eastern United States and Canada (1), including the eastern 1/2 of Oklahoma and Texas (2-4). In Oklahoma, the Northern Parula appears around March 25 and may remain until late September or early October (5). During the breeding season in west Texas, several individuals (including singing males) had been seen in the Big Bend Park area (Brewster County); however, there was no evidence of nesting (6). Western-most records for Oklahoma include Comanche County (7) and Cimarron County in the Panhandle (3). Wintering areas include central Mexico south to Guatemala and Belize and the islands of the Greater and Lesser Antilles (8, 9). Some southern states, e.g., Texas (2); Lousiana (10) also have supported wintering Northern Parula including a rare occurrence in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas (4). In this paper, I report the latest findings on the Northern Parula with emphasis on its ecology and behavior, especially studies in Oklahoma and Texas. BEHAVIOR The foraging strategy of the Northern Parula is often compared to that of chickadees and titmice (Family Paridae) because it is able to dart in and out of the tips of vegetation (11). This type of foraging movement, with >50% of movements on small limbs, is due to small body size, which enables the Northern Parula to use a foraging niche more effectivly than many other warblers, e.g., some Dendroica species (12). -

Northern Parula Setophaga Americana

Northern Parula Setophaga americana Folk Name: Blue Yellow-backed Warbler Status: Breeder Abundance: Uncommon to Fairly Common Habitat: Bottomland forests—damp, low woods “Cute.” That seems to be the most common adjective ascribed to this petite, energetic warbler. Although, “adorable” is certainly in the running as well. It is a colorful bird with a mix of blue gray, yellow green, bright yellow, and bold white, with the addition of a dab of reddish and black on the males. It is our smallest member of the warbler family, about the size of the tiny Blue-gray Gnatcatcher, but this bird has a very short tail. As such, it can be hard to see amongst the foliage while it is foraging for insects and spiders in the top of a tree. Fortunately, the male is quite a loud and persistent singer and a patient observer, following the bird’s song, may soon be rewarded with a view of it. The song of the Northern Parula has been variously R. B. McLaughlin found a Northern Parula nest with described as a wind-up zee-zee-zee trill with an abrupt, eggs in Iredell County on May 11, 1887. In December of punctuated, downward zip note at the end, or as a “quaint that year, he published a brief article describing another drowsy, little gurgling sizzle, chip-er, chip-er, chip-er, nest of the Northern Parula which he had found in chee-ee-ee-ee.” It breeds in much of the eastern United Statesville several years earlier. He first noticed a clump of States and throughout both Carolinas. -

Prairie Ridge Species Checklist 2018

Prairie Ridge Species Checklist Genus species Common Name Snails Philomycus carolinianus Carolina Mantleslug Gastrocopta contracta Bottleneck Snaggletooth Glyphalinia wheatleyi Bright Glyph Triodopsis hopetonensis Magnolia Threetooth Triodopsis juxtidens Atlantic Threetooth Triodopsis fallax Mimic Threetooth Ventridens cerinoideus Wax Dome Ventridens gularis Throaty Dome Anguispira fergusoni Tiger Snail Zonitoides arboreus Quick Gloss Deroceras reticulatum Gray Garden Slug Mesodon thyroidus White-lip Globe Slug Stenotrema stenotrema Inland Stiltmouth Melanoides tuberculatus Red-rim Melania Spiders Argiope aurantia Garden Spider Peucetia viridans Green Lynx Spider Phidippus putnami Jumping Spider Phidippus audax Jumping Spider Phidippus otiosus Jumping Spider Centipedes Hemiscolopendra marginata Scolopocryptops sexspinosus Scutigera coleoptrata Geophilomorpha Millipedes Pseudopolydesmus serratus Narceus americanus Oxidus gracilis Greenhouse Millipede Polydesmidae Crayfishes Cambarus “acuminatus complex” (= “species C”) Cambarus (Depressicambarus) latimanus Cambarus (Puncticambarus) (="species C) Damselflies Calopteryx maculata Ebony Jewelwing Lestes australis Southern Spreadwing Lestes rectangularis Slender Spreadwing Lestes vigilax Swamp Spreadwing Lestes inaequalis Elegant Spreadwing Enallagma doubledayi Atlantic Bluet Enallagma civile Familiar Bluet Enallagma aspersum Azure Bluet Enallagma exsulans Stream Bluet Enallegma signatum Orange Bluet Ischnura verticalis Eastern Forktail Ischnura posita Fragile Forktail Ischnura hastata Citrine -

Ne:Otropigalmigr:Ant Landbird Monitoring Program for Maineand..New' Brunswick: Assessing Coastal Importance and Management Strategies

NE:OTROPIGALMIGR:ANT LANDBIRD MONITORING PROGRAM FOR MAINEAND..NEW' BRUNSWICK: ASSESSING COASTAL IMPORTANCE AND MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES Norman Famous, Wildlife Ecologist PROJECT SUMMARY Populations of many Neotropical migrant landbirds and shorebirds have shown both long and short-term declines in the Northeastern U.S. and adjacent Canada. The causes of these declines are not entirely understood and vary among species. A cooperative initiative linking Federal and Provincial agencies, private landowners, conservation organizations, industry and field ornithologists was implemented in 1993 to monitor breeding and migratory bird populations in structurally stable boreal forests, pine-spruce woodlands, bogs and fens in the Bay of Fundy ecological zone in Maine and coastal New Brunswick, as well as the Acadian Peninsula in NW New Brunswick. Careful selection of monitoring sites and control of observer expertise are being exercised. Most sites are relatively free from future habitat fragmentation, large changes in habitat structure, human disturbances and insect infestations. The distribution of birds and vegetation characteristics are being mapped within fixed diameter point count circles along 25 new census routes located within 0.5 km of the coast or on larger islands. Birds were censused and mapped along 13 BBS routes in the region. Twenty-two boreal bogs and fens were surveyed. Habitat use by birds and habitat changes over time will be evaluated in addition to long term population trends in both new routes and BBS routes. Breeding season bird use and vegetation change in nine mined peatlands undergoing natural and human-induced restoration are being monitored in Maine and New Brunswick. (Comment, the habitat work was not completed during subsequent years due to insufficient funds.) Seventy-eight fall migration fixed-diameter area-search point count circles were censused every ten days from August through October at six coastal sites. -

Discrimination Between Regional Song Forms in the Northern Parula

Wilson Bull., 108(2), 1996, pp. 335-341 DISCRIMINATION BETWEEN REGIONAL SONG FORMS IN THE NORTHERN PARULA DANIEL J. REGELSKI,*’ AND RALPH R. MOLDENHAUER’ ABSTRACT.-DiStinCtly different territorial (Type A) song forms characterize western and eastern populations within the breeding range of the Northern Panda (Parula americana). We conducted playback experiments to determine if territorial males respond differentially to the two song forms. Male response is stronger to Type A songs of their own population than to the songs of the other population (two-tailed Wilcoxon test, P < 0.001). The possible basis for this discrimination is discussed. Received 3 Dec. 1993, accepted 15 Oct. 1995. Many oscine species exhibit geographic song variation (Thielcke 1969), and some of these species ’ songs vary microgeographically, with two or more small scale local dialects (Kroodsma 1981, Tomback et al. 1983, Kroodsma et al. 1984). In species such as the Mourning Warbler (Opo- rornis philudelphia), there is macrogeographical song variation, with two or more distinct and widespread regional song forms or song populations (Pitocchelli 1990). The Northern Parula (Purula umericunu) has two primary song types, Types A and B (Moldenhauer 1992). Spectrographic analysis of Type A songs from throughout the breeding range by Moldenhauer (1992) re- vealed an eastern and a western song population (Fig. 1) whose songs are characterized by distinctly different terminal notes (Fig. 2). Playback experiments have shown that in species whose song varies geographically, territorial males can often distinguish between different dialects or song forms, as inferred from the intensity of response to playback (Kroodsma et al. 1984, Ritchison 1985). -

Jessica Sosnicki

Uncovering Willard Ellery Treat Jessica Sosnicki Biol 216: Zoology Dr. Karen Francl Submission for 2009 Winesett Awards for Library Research Jessica Sosnicki Biol 216: Zoology Dr. Francl Biography: Willard Ellery Treat The Biology Department at Radford University has a vast set of specimens collected over the years. Of that collection, Willard E. Treat contributes a small, but significant part. Born almost a century and a half ago, there is little known about him and why his collection ended up at Radford University. However, his specimens are still important to natural history, especially here at Radford. Willard Ellery Treat was born on July 31, 1865 in East Hartford, Connecticut, where he resided most of his life (U.S. Federal Census, 1870). His father, Ellery Treat, worked in East Hartford as a bookmaker, while his mother, Eunice, was a homemaker. According to the 1870 Federal Census, Willard had a sister, Adella (“Della”) G. Treat as well. Although, the Census did not indicate other siblings, he also had two brothers, William Howard Treat and Edwin Cuyler Treat (Warner, 1902). Around the age of 20, Willard attended Wesleyan College in Middletown, Connecticut not far from his hometown. In college, he was a member of Alpha Alpha, a Wesleyan chapter of Chi Psi. The Sixth Decennial Catalogue of Chi Psi states he was part of the Class of 1888 (Warner, 1902). However, Willard only attended one year at Wesleyan; he left during his sophomore year. His two brothers also attended Wesleyan. Like his brother, William Treat left his second year. Out of the three brothers, Edwin Cuyler Treat is the only one that actually graduated from Wesleyan, in 1894. -

Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers

Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Brandan L. Gray August 2019 © 2019 Brandan L. Gray. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers by BRANDAN L. GRAY has been approved for the Department of Biological Sciences and the College of Arts and Sciences by Donald B. Miles Professor of Biological Sciences Florenz Plassmann Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT GRAY, BRANDAN L., Ph.D., August 2019, Biological Sciences Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers Director of Dissertation: Donald B. Miles In a rapidly changing world, species are faced with habitat alteration, changing climate and weather patterns, changing community interactions, novel resources, novel dangers, and a host of other natural and anthropogenic challenges. Conservationists endeavor to understand how changing ecology will impact local populations and local communities so efforts and funds can be allocated to those taxa/ecosystems exhibiting the greatest need. Ecological morphological and functional morphological research form the foundation of our understanding of selection-driven morphological evolution. Studies which identify and describe ecomorphological or functional morphological relationships will improve our fundamental understanding of how taxa respond to ecological selective pressures and will improve our ability to identify and conserve those aspects of nature unable to cope with rapid change. The New World wood warblers (family Parulidae) exhibit extensive taxonomic, behavioral, ecological, and morphological variation. -

Wood Warblers Wildlife Note

hooded warbler 47. Wood Warblers Like jewels strewn through the woods, Pennsylvania’s native warblers appear in early spring, the males arrayed in gleaming colors. Twenty-seven warbler species breed commonly in Pennsylvania, another four are rare breeders, and seven migrate through Penn’s Woods headed for breeding grounds farther north. In central Pennsylvania, the first species begin arriving in late March and early April. Louisiana waterthrush (Parkesia motacilla) and black and white warbler (Mniotilta varia) are among the earliest. The great mass of warblers passes through around mid-May, and then the migration trickles off until it ends in late May by which time the trees have leafed out, making it tough to spot canopy-dwelling species. In southern Pennsylvania, look for the migration to begin and end a few days to a week earlier; in northern Pennsylvania, it is somewhat later. As summer progresses and males stop singing on territory, warblers appear less often, making the onset of fall migration difficult to detect. Some species begin moving south as early as mid and late July. In August the majority specific habitat types and show a preference for specific of warblers start moving south again, with migration characteristics within a breeding habitat. They forage from peaking in September and ending in October, although ground level to the treetops and eat mainly small insects stragglers may still come through into November. But by and insect larvae plus a few fruits; some warblers take now most species have molted into cryptic shades of olive flower nectar. When several species inhabit the same area, and brown: the “confusing fall warblers” of field guides. -

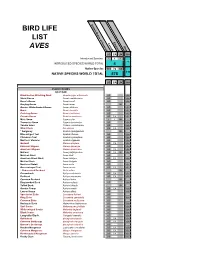

Bird Life List Aves

United States of America BIRD LIFE LIST England Canada AVES Ohio US CA UK OH Introduced Species 5 4 4 4 INTRODUCED SPECIES WORLD TOTAL 4 Native Species 544 72 44 310 NATIVE SPECIES WORLD TOTAL 578 US CA UK OH ANSERIFORMES ANATIDAE Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna autumnalis US OH Snow Goose Anser caerulescens US OH Ross's Goose Anser rossii US OH Greylag Goose Anser anser UK Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons US OH Brant Branta bernicla US OH Cackling Goose Branta hutchinsii US OH Canada Goose Branta canadensis US CA i OH Mute Swan Cygnus olor i i UK i Trumpeter Swan Cygnus buccinator US OH Tundra Swan Cygnus columbianus US OH Wood Duck Aix sponsa US CA OH * Garganey Spatula querquedula UK Blue-winged Teal Spatula discors US OH Cinnamon Teal Spatula cyanoptera US OH Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata US OH Gadwall Mareca strepera US CA OH Eurasian Wigeon Mareca penelope US OH American Wigeon Mareca americana US CA OH Mallard Anas platyrhynchos US CA UK OH Mexican Duck Anas diazi US American Black Duck Anas rubripes US CA OH Mottled Duck Anas fulvigula US Northern Pintail Anas acuta US OH Green-winged Teal Anas crecca US CA OH * Red-crested Pochard Netta rufina UK Canvasback Aythya valisineria US CA OH Redhead Aythya americana US CA OH Common Pochard Aythya ferina UK Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris US OH Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula UK Greater Scaup Aythya marila US CA OH Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis US OH Spectacled Eider Somateria fischeri US King Eider Somateria spectabilis US OH Common Eider Somateria mollissima US -

Species Included in Categories A, B & C Scientific

Species included in categories A, B & C Scientific name Race Category 1 Mute Swan Cygnus olor -- A / C1 2 Bewick’s Swan Cygnus columbianus bewickii A >> Tundra Swan columbianus -- 3 Whooper Swan Cygnus cygnus -- A 4 Bean Goose Anser fabalis fabilis A >> Tundra Bean Goose rossicus -- 5 Pink-footed Goose Anser brachyrhynchus -- A 6 White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons flavirostris A >> Russian White-fronted Goose albifrons -- 7 Lesser White-fronted Goose Anser erythropus -- A 8 Greylag Goose Anser anser anser A / C1 9 Snow Goose Anser caerulescens caerulescens A / D1 >> Greater Snow Goose atlanticus -- 10 Cackling Goose Branta hutchinsii hutchinsii A 11 Canada Goose Branta canadensis canadensis A / C1 >> Todd's Canada Goose interior -- 12 Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis -- A / C1 13 Brent Goose Branta bernicla hrota A >> Dark-bellied Brent Goose bernicla -- >> Black Brant nigricans -- 14 Ruddy Shelduck Tadorna ferruginea -- B / D1 15 Shelduck Tadorna tadorna -- A 16 Mandarin Duck Aix galericulata -- C1 17 Wigeon Anas penelope -- A 18 American Wigeon Anas americana -- A 19 Gadwall Anas strepera -- A 20 Baikal Teal Anas formosa -- A / D1 21 Teal Anas crecca crecca A 22 Green-winged Teal Anas carolinensis -- A 23 Mallard Anas platyrhynchos platyrhynchos A / C1 24 American Black Duck Anas rubripes -- A 25 Pintail Anas acuta acuta A 26 Garganey Anas querquedula -- A 27 Blue-winged Teal Anas discors -- A 28 Shoveler Anas clypeata -- A 29 Red-crested Pochard Netta rufina -- A 30 Pochard Aythya ferina -- A 31 Redhead Aythya americana -- A 32 Ring-necked -

Wildlife and Upland Oak Forests

WILDLIFE AND UPLAND OAK FORESTS James G. Dickson1 Abstract—The oak forests of the eastern U.S. have always been diverse as well as dynamic; continually molded and influenced by a variety of natural and anthropogenic forces. These forests support thousands of species of plants, untold numbers of insects and other invertebrates, and hundreds of species of vertebrate wildlife. Because of the large number of species, I focus on species and communities of special interest or concern. Acorns are a primary fall and winter diet item of many vertebrate species. Acorns build energy reserves, which are very important for winter survival and success- ful reproduction for a number of species. The wild turkey, white-tailed deer, and American black bear, which suffered and were very limited a century ago, have been restored and now flourish. There are a wide variety of bird species associated with upland oak forests; most associated with specific habitat attributes. Generally, there is concern for two categories of birds: neartic-neotropical migratory birds, and early successional, grass-forb associated birds. Bats are important ecological components of oak forests; several species of cave bats are endangered and there is concern for others. Even though upland oak ecosystems are mostly xeric, the forests support a high diversity of reptile and amphibian species, and provide important habitat for many species. HISTORY In the late 1800s and early 1900s the wholesale clearing of Around 10,000 BC or even earlier, the first humans arrived the forest and the direct harvest of many species of animals in North America. Here they found several species of mega- were profound.