City & Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Govt. Senior Secondary Schools School Boys/ Rural/ Name of Assembly Parliamentry Sr.No

List Of Govt. Senior Secondary Schools School Boys/ Rural/ Name of Assembly Parliamentry Sr.No. Name of School/Office Code Girls Urban Block Constituency Constituency Ambala 81 1 GSSS Adhoya 10 Co-Edu Rural Barara 06-MULLANA (SC) AC AMBALA 2 GSSS Akbarpur 53 Co-Edu Rural Naraingarh 03-NARAINGARH AC AMBALA 3 GSSS Alipur 70 Co-Edu Rural Barara 06-MULLANA (SC) AC AMBALA 4 GSSS Ambala Cantt (Rangia Mandi) 6 Co-Edu Urban Ambala-II (Cantt) 04-AMBALA CANTT AC AMBALA 5 GSSS Ambala Cantt. (B.C. Bazar) 4 Co-Edu Urban Ambala-II (Cantt) 04-AMBALA CANTT AC AMBALA 6 GSSS Ambala Cantt. (Bakra Market) 5 Co-Edu Urban Ambala-II (Cantt) 04-AMBALA CANTT AC AMBALA 7 GSSS Ambala Cantt. (Main Branch) 171 Co-Edu Urban Ambala-II (Cantt) 04-AMBALA CANTT AC AMBALA 8 GSSS Ambala Cantt. (Ram Bagh 7 Co-Edu Urban Ambala-II (Cantt) 04-AMBALA CANTT AC AMBALA Road) 9 GSSS Ambala City (Baldev Nagar) 8 Co-Edu Urban Ambala-I (City) 05-AMBALA CITY AC AMBALA 10 GGSSS Ambala City (Baldev Nagar) 69 Girls Urban Ambala-I (City) 05-AMBALA CITY AC AMBALA 11 GGSSS Ambala City (Model Town) 172 Girls Urban Ambala-I (City) 05-AMBALA CITY AC AMBALA 12 GGSSS Ambala City (Police Line) 143 Girls Urban Ambala-I (City) 05-AMBALA CITY AC AMBALA 13 GSSS Ambala City (Prem Nagar) 9 Co-Edu Urban Ambala-I (City) 05-AMBALA CITY AC AMBALA 14 GSSS Babyal 11 Boys Urban Ambala-II (Cantt) 04-AMBALA CANTT AC AMBALA 15 GSSS Badhauli 14 Co-Edu Rural Naraingarh 03-NARAINGARH AC AMBALA 16 GSSS Baknaur 71 Co-Edu Rural Ambala-I (City) 05-AMBALA CITY AC AMBALA 17 GSSS Ballana 12 Co-Edu Rural Ambala-I (City) -

9-Ravi-Agarwal-Ridge.Pdf

Fight for a forest RAVI AGARWAL From where comes this greenery and flowers? 15% of the city’s land, though much What makes the clouds and the air? of it has been flattened. The decidu- – Mirza Ghalib ous arid scrub forest of the ridge still provides an unique ecosystem, which THE battle for protecting Delhi’s today lies in the heart of the modern green lungs, its prehistoric urban for- city, and is critical for its ecological est, has never been more intense than health. Though citizen’s action has now. The newly global city, located in managed to legally protect1 about a cusp formed by the tail end of the 1.5 7800 ha of the forest scattered in four billion year old, 800 km long Aravalli mountain range as it culminates at the * Ravi Agarwal is member of Srishti and river Yamuna, is the aspirational capi- founding Director of Toxics Link, both envi- 48 tal of over 15 million people. ronmental NGOs. He has been involved in the ridge campaign since 1992, and was inducted The hilly spur known as the into the Ridge Management Board in 2005. Delhi Ridge once occupied almost He is an engineer by training. SEMINAR 613 – September 2010 distinct patches, the fight for the ridge besides protecting the city from desert Dynasty in the 13th and 14th centuries forest has been long and is ongoing. sands blowing in from Rajasthan and marked by the towering Qutab Land is scarce, with competing uses (south of Delhi). Most importantly, for Minar. in the densely populated city, sur- an increasingly water scarce city, the rounded by increasingly urbanized ridge forest and the river Yamuna once peripheral townships of Gurgaon, formed a network of water channels, Even though the Delhi Ridge forest Faridabad and Noida. -

Urban Heat Island Assessment for a Tropical Urban Airshed in India

Atmospheric and Climate Sciences, 2012, 2, 127-138 127 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/acs.2012.22014 Published Online April 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/acs) Urban Heat Island Assessment for a Tropical Urban Airshed in India Manju Mohan1, Yukihiro Kikegawa2, B. R. Gurjar3, Shweta Bhati1, Anurag Kandya1, Koichi Ogawa2 1Centre for Atmospheric Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology-Delhi, Delhi, India 2Department of Environmental Systems, Meisei University, Tokyo, Japan 3Department of Civil Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology, Roorkee, India Email: [email protected] Received February 6, 2012; revised March 16, 2012; accepted March 28, 2012 ABSTRACT There has been paucity of field campaigns in India in past few decades on the urban heat island intensities (UHI). Re- mote sensing observations provide useful information on urban heat island intensities and hotspots as supplement or proxy to in-situ surface based measurements. A case study has been undertaken to assess and compare the UHI and hotspots based on in-situ measurements and remote sensing observations as the later method can be used as a proxy in absence of in-situ measurements both spatially and temporally. Capital of India, megacity Delhi has grown by leaps and bounds during past 2 - 3 decades and strongly represents tropical climatic conditions where such studies and field cam- paigns are practically non-existent. Thus, a field campaign was undertaken during summer, 2008 named DELHI-I (Delhi Experiments to Learn Heat Island Intensity-I) in this megacity. Urban heat island effects were found to be most dominant in areas of dense built up infrastructure and at commercial centers. -

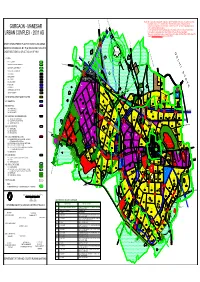

GURGAON - MANESAR on the Website for All Practical Purposes

FROM FARUKHNAGAR FROM FARUKHNAGAR NOTE: This copy is a digitised copy of the original Development Plan notified in the Gazette.Though precaution has been taken to make it error free, however minor errors in the same cannot be completely ruled out. Users are accordingly advised to cross-check the scanned copies of the notified Development plans hosted GURGAON - MANESAR on the website for all practical purposes. Director Town and Country Planning, Haryana and / or its employees will not be liable under any condition TO KUNDLI for any legal action/damages direct or indirect arising from the use of this development plan. URBAN COMPLEX - 2031 AD The user is requested to convey any discrepancy observed in the data to Sh. Dharm Rana, GIS Developer (IT), SULTANPUR e-mail id- [email protected], mob. no. 98728-77583. SAIDPUR-MOHAMADPUR DRAFT DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR CONTOLLED AREAS V-2(b) 300m 1 Km 800 500m TO BADLI BADLI TO DENOTED ON DRG.NO.-D.T.P.(G)1936 DATED 16.04.2010 5Km DELHI - HARYANA BOUNDARY PATLI HAZIPUR SULTANPUR TOURIST COMPLEX UNDER SECTION 5 (4) OF ACT NO. 41 OF 1963 AND BIRDS SANTURY D E L H I S T A T E FROM REWARI KHAINTAWAS LEGEND:- H6 BUDEDA BABRA BAKIPUR 100M. WIDE K M P EXPRESSWAY V-2(b) STATE BOUNDARY WITH 100M.GREEN BELT ON BOTH SIDE SADHRANA MAMRIPUR MUNICIPAL CORPORATION BOUNDARY FROM PATAUDI V-2(b) 30 M GREEN BELT V-2(b) H5 OLD MUNICIPAL COMMITTEE LIMIT 800 CHANDU 510 CONTROLLED AREA BOUNDARY 97 H7 400 RS-2 HAMIRPUR 30 M GREEN BELT DHANAWAS VILLAGE ABADI 800 N A J A F G A R H D R A I N METALLED ROAD V-2(b) V2 GWS CHANNEL -

Digital Issue 400.00 `

62 2020 lajournal.in ISSN 0975-0177 | cklB DIGITAL ISSUE 400.00 ` landscape 1 62 | 2020 INSTALLINGINSTALLING TWO-WIRE TWO-WIRE INSTALLINGJustJust Got Got aTWO-WIRE Lot a LotEasier Easier INSTALLINGJust Got a Lot TWO-WIRE Easier Just Got a Lot Easier INSTALLING TWO-WIRE Just Got a Lot Easier With the revolutionary EZ Decoder System, you get all the advantages of two-wire installations with simpler, more cost-effectiveWith the technology.revolutionary Plug EZ in theDecoder EZ-DM System, two-wire you output get allmodule the advantagesto enable up ofto two-wire54 stations installations of with simpler, you get all the advantages of two-wire installations with simpler, Withirrigation,With the the revolutionary revolutionary plusmore a master cost-effective valve,EZ EZ Decoder Decoder on atechnology. single System, System, pair of Plugwires. you in get the allEZ-DM the advantages two-wire output of two-wire module installations to enable up with to 54 simpler, stations of Withmore the cost-effective revolutionaryirrigation, technology. plusEZ Decoder a master System,Plug valve, in the you on EZ-DMget a singleall thetwo-wire advantagespair of output wires. of two-wiremodule toinstallations enable up with to 54simpler, stations of moremoreirrigation, cost-effective cost-effective plus a master technology. technology. valve, onPlug a insinglePlug the in EZ-DMpair the of two-wirewires.EZ-DM two-wireoutput module output to enable module up to to54 enablestations upof to 54 stations of irrigation,irrigation, plusplus a amaster master valve, valve, -

Unpaid Dividend-16-17-I2 (PDF)

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L72200KA1999PLC025564 Prefill Company/Bank Name MINDTREE LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 17-JUL-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 737532.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) 49/2 4TH CROSS 5TH BLOCK MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANAND NA KORAMANGALA BANGALORE INDIA Karnataka 560095 72.00 24-Feb-2024 2539 unpaid dividend KARNATAKA 69 I FLOOR SANJEEVAPPA LAYOUT MIND00000000AZ00 Amount for unclaimed and A ANTONY FELIX NA MEG COLONY JAIBHARATH NAGAR INDIA Karnataka 560033 72.00 24-Feb-2024 2646 unpaid dividend BANGALORE PLOT NO 10 AIYSSA GARDEN IN301637-41195970- Amount for unclaimed and A BALAN NA LAKSHMINAGAR MAELAMAIYUR INDIA Tamil Nadu 603002 400.00 24-Feb-2024 0000 unpaid dividend -

Sco 9P, Old Judicial Complex, Civil7838400440 Haryana 122001

2. 37T: YT Tt, TOTORHO, frGTET TATA, BM HEYTR TETT iTT HTRECodeof Criminal Procedure, 1973 7ET YET TfTT 1 uT TI Route No.1 Sr. Name of Hospital Address Contact No. Name/Designation and No. Mob.No. of Duty Magistrate Pushpanjali Civil Line Road, near Rajiv 0124-4770000 Sh. Satish Rohilla, Hospital Chowk, Gurugram - 122001 DRCS, Mob.No. Indigo diagnostic Sco 9P, old judicial complex, civil7838400440 (8901123200) hospital lines road, Gurugram 3 Aarvy Hospital 530/18 Civil Lines Opp Nelhru 01244222270 Civil Lines Stadium, Gurugram -122001 Narayana Mother Jharsa road, housing board colony, | 9953168569 and Childcare patel nagar, Gurugram Center Aggarwal centre House no. 157,jharsa road, 9810808S70 for diabetes and housing board colony, patel nagar, cancer care Gurugram Bhanot Hospital 188/18, Jharsa road, friends 01242322222 colony, Gurugram |7 Nidaan Hospital 96, jharsa road, kirti nagar, sector IS part 1, sector 15 Gurugram Bansal Medicare C2, Sector 15 part 1, near 01242324727. vigilance olfice, Gurugram 237727 ALPINE Plot no 140, near mother dairy, 0124 425 3838 HOSPITAL sector 15 part 2, Gurugram Route No.2 Aryan Hospital Old Railway Road Gurugram - 01244910020 Sh. Ram Kumar, ARCS, 122001 2 7495073889 Chiranjiv Hospital New Colony, Haripura, Gurugram, 01244100529 Haryana 122001 3 Sanjeevani Sanjeevani Hospital, Sector 7 Hospital, Sector 7 01244076442 Geeta nrsing -11. New C'olmy Rd, near State 0124 231 2100 home Bank ot Indin, Shivpuri Eixtension, Sector 7, Gurugran, Ilaryan 12.2006 Triveni Near Canara Bank, Nenr Dhobi 098100 93892 Ghaat, Old Railway Rd. Sector 8, Gurugranm, Haryanan 122001 Aastha medicare louse no 233-P, Ashok Vihar. 080 4809 2648 Sector 5, Gurugram, IHnrynna 1.2.2001 NR Healheare Ner Sheetlka Mata Mandir, 238, 9625529114 Center Sector 5, Old Gurugram Sneh Hospital Main Railway Rond, Ashok Vihar,. -

Chitin Degrading Potential of Bacteria from Extreme and Moderate Environment

In diJn Journ al or Experi mentJI Biology Vol. 4 1. March 2003. pp. 248-254 Chitin degrading potential of bacteria from extreme and moderate environment N N Nawani & B P Kapadni s* Department of Microbiology. Uni versi ty or Pune. Pune 4 11 007. In dia Recei ved 22 Nove lllber 2002; revis ed 19 j allllclI] 2003 Five hundred chitin-degrad ing bacteria we re iso lated rrom 20 different locations. Hi gh percenta ge of potent chitin degraders was obtain ed fro m po llu ted regions. Potent chit in- degrading bacteri a were selected by primary and ,eeondary scree nin g. Among th e se lected isolates. 78% we re rcprcsc nt cd by the gcn us STreplUlllyces. Majority of th c iso lat es had good chitinolys is relati ve to the growt h although iso lates with beller growth were al so seen. Such isolat es arc important 1'0 1' the producti on of SCP from chitinous wastes. The potent iso lates be longed to th e genera STrepf()/.'lyces. KirasalUsporia. Sacc/wwpolyspol'{[. Nocardioides. Nocardiollsis. I-Ierbidospora. MicrOIllOIlOSP0/'{f. Micwbispo/'{f. I ICTill oplalle..... SerraTia. iJacilllis and Pse lidolllollas. Thi s study form s J comprehensive base for the study of divcrsity of chitinolytic syste ms of bacte ri J. Ch itin , the ~-I , 4 linked polymer of N-acetylgluco Materials and Methods samine is the second most ab undant polysaccharide in The locati ons of sa mpling included habitats classi nature. Chitin is a structural component of th e ce ll fied as ex treme and moderate as shown in Tab le I, wa ll s of fungi as we ll as of shell s or cuti cles of arthro fro m where soi I and water samples were co ll ec ted pods, cru staceans, insects and mollusks. -

Developing a Model for Corporate Career Building Programme (Ccbp) Using Hrm Tools and Techniques for Management Students in Pune City”

“DEVELOPING A MODEL FOR CORPORATE CAREER BUILDING PROGRAMME (CCBP) USING HRM TOOLS AND TECHNIQUES FOR MANAGEMENT STUDENTS IN PUNE CITY” To Order Full/Complete PhD Thesis 1 Thesis (Qualitative/Quantitative Study with SPSS) & PPT with Turnitin Plagiarism Report (<10% Plagiarism) In Just Rs. 45000 INR* Contact@ Writekraft Research & Publications LLP (Regd. No. AAI-1261) Mobile: 7753818181, 9838033084 Email: [email protected] Web: www.writekraft.com Contents Title Page No. Acknowledgement ...................................................................................................................... i Guide Certificate ........................................................................................................................ ii Declaration ................................................................................................................................. iii Abstract ......................................................................................................................................... iv Abbreviation ............................................................................................................................. xix List of Tables.............................................................................................................................. xx List of Graphs......................................................................................................................... xxv List of Diagrams ............................................................................................................... -

Countryside-Brochure.Pdf

- WHERE NATURE RESIDES - LOSE YOURSELF IN AN ORCHESTRA OF TRANQUILITY. LISTEN TO NATURE’S LIVE CONCERT. In the green valleys surrounding Pune is a small hamlet known as Sangrun. With the Sahyadri Range to the north and Khadakwasla Lake to the south, it’s cocooned in nature’s blanket. The winds play a melodious tune and the trees sway to this composition. Water bounces off the rocks and birds play hide ‘n’ seek with the clouds. Truly, this is nature’s concert coming to life. And you’re the audience about to drown in its rhapsody. COUNTRYSIDE: THE HEADLINER OF THE CONCERT Every concert needs a star attraction. And the one at Sangrun is ‘Countryside’ by Pate Developers. Located near the famous Peacock Bay, a part of Khadakwasla backwaters, Countryside is your chance for a tête-à-tête with nature. Exclusive bungalows and NA plots with topnotch amenities make weekends here seem surreal. All you need to do is pack your favorite books, woolens and coffee. DROWN YOURSELF IN NATURE’S MELODY. EVERY WEEKEND. Weekday work stress is a fact of life that we all have to live with. And on weekends we find ourselves doing home chores and completing unfinished personal work. So, when does one get exclusive family time to rejuvenate and relax? ‘Countryside’ is the quintessential weekend getaway. Being enveloped by nature, it’s pure air, fresh water and rustic surroundings will relax your mind and body. More importantly, it’ll give you quality time with family and some much needed ‘me’ time. Take a walk in the woods or simply sit in your private garden with a hot cuppa; either way weekends will never be the same again. -

Pune Urban Biodiversity-A Case of Millennium

.. "- \. ill } JOURNAL OF ECOLOGICAL SOCIETY Val.s 13 and 14, 2000-2001 Biodiversity Profile of an Urban Area Special Double Issue Foreword Urban biodiversity sounds like a misnomer! What diversity of (non-human) life a burgeoning city with three million plus human population is likely to retain? The proof of the pudding is in eating. Here is a gallant attempt to draw a picture of the extant biodiversity of the Pune urban area based on field-work. Enthusiastic collegians under the guidance of their teachers have probed various natural and urban habitats to complete this picture. The wherewithal was provided by Ranwa, a Pune-based NGO deeply interested in the study and conservation of nature. The guest editors for this volume, Prof. Sanjeev Nalavade and Utkarsh Ghate, themselves involved in inspiring this effort have painstakingly edited the available material to give a shape and form that is at once interesting and informative. Hopefully this effort will prove a bench-mark and a useful guide in formulating the future development policies and plans of the Pune urban area. This special double issue is grandly embellished by excellent photographs. Thanks to the contribution made by leading nature photographers of Pune. The web of life that still permeates our urban setting proves the tenacity and adaptive capacities of natural beings in the face of insuperable odds. Notwith- standing the loss of invertebrates and fish species and some of the interesting birds, nature shows extraordinary capabilities to cling to whatever habitat traces that remain. We, the citizens of Pune, must remember that the biodiversity pictured here is not because of any conscious efforts on our part. -

Item No. 05 to 08 Court No. 1 BEFORE the NATIONAL

WWW.LIVELAW.IN Item No. 05 to 08 Court No. 1 BEFORE THE NATIONAL GREEN TRIBUNAL PRINCIPAL BENCH, NEW DELHI Original Application No. 144/2015 Jaipal Singh Applicant Versus Lt. Governor, Delhi & Ors. Respondent(s) WITH Original Application No. 58/2013 (M.A No. 898/2013, M.A. No. 922/2017, M.A. No. 329/2018, I.A. No. 387/2019 & I.A. No. 388/2019) Sonya Ghosh Applicant Versus Govt. of NCT of Delhi & Ors. Respondent(s) WITH Original Application No.116/2015 (M.A. No. 327/201 & M.A. No. 589/2015) Prof. Imtiaz Ahmed & Ors. Applicant(s) Versus State of NCT of Delhi & Ors. Respondent(s) WITH M.A. No. 258/2015 IN Original Application No. 10/2014 Pavit Singh Applicant(s) Versus The State of NCT Of Delhi & Ors. Respondent(s) Date of hearing: 15.01.2021 CORAM: HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE ADARSH KUMAR GOEL, CHAIRPERSON HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE SHEO KUMAR SINGH, JUDICIAL MEMBER HON’BLE DR. NAGIN NANDA, EXPERT MEMBER Applicant: Mr. Raj Panjwani, Senior Advocate (Amicus Curiae) and Mr. Aagney Sail, Advocate in O.A. No. 58/2013 Ms. Meera Gopal, Advocate in O.A. No. 116/2015 Respondent: Mr. Sanjay Dewan, Advocate for Forest Department, NCT of Delhi Mr. Kush Sharma, Advocate for DDA Ms. Puja Kalra, Advocate for North MCD 1 WWW.LIVELAW.IN ORDER 1. The common issue in this group of matters is conservation and protection of Delhi Ridge which is an extension of Aravalli Range extending from Tughlaqabad and branching out in Wazirabad in the north and also other parts of Delhi.