Conflict of Laws

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The ACLU of Florida Opposes This Bill Because It Is Designed to Further

Alicia Devine/Tallahassee Democrat The ACLU of Florida opposes this bill because it The murders of George Floyd, protesters and the injustices of our is designed to Breonna Taylor, and so many criminal legal system. others at the hands of police further silence, Floridians wishing to exercise their reinvigorated Floridians’ calls for punish, and constitutional rights would have to police reform and accountability. weigh their ability to spend a night criminalize those Millions took to the streets to in jail if the protest is deemed an advocating for exercise their First Amendment “unlawful assembly.” Peaceful racial justice and rights and demand justice. protesters could be arrested and an end to law Under existing law, these peaceful charged with a third-degree felony enforcement’s protests were met with tear gas, for “committing a riot” even if they excessive use of rubber bullets, and mass arrests. didn’t engage in any disorderly and force against Black Under existing law, armed officers violent conduct. in full riot gear repeatedly used and brown people. Floridians need justice – real excessive force against peaceful police accountability and criminal unarmed protesters. justice reform. Florida’s law Florida’s militaristic response enforcement and criminal legal against Black protesters and their system have no shortage of tools to allies demanding racial justice keep the peace and punish violent stands in stark contrast to the actors, and they’ve proven their lackluster, and at times complicit, tendency time and time again to police response we saw to the misapply these tools to punish failed coup by white supremacist Black and brown peaceful terrorists in D.C. -

Making the Best of Felony Murder

University at Buffalo School of Law Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2011 Making the Best of Felony Murder Guyora Binder University at Buffalo School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Guyora Binder, Making the Best of Felony Murder, 91 B.U. L. Rev. 403 (2011). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/journal_articles/287 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES MAKING THE BEST OF FELONY MURDER GuYoRA BINDER* INTRODUCTION: THE WORST OF FELONY MURDER ........................................ 404 I. THE PRINCIPLES OF FELONY MURDER LIABILITY ............................... 411 A. The Constructive Interpretationof Legal Principle .................... 411 B. The Development of Felony Murder Liability ............................. 413 C. Objections to Felony Murder ...................................................... 421 1. Theoretical O bjections ........................................................... 422 2. Constitutional Objections ...................................................... 428 D. Felony Murder as a Crime of Dual Culpability ......................... -

30-15-1. Criminal Damage to Property. 30-15-3. Damaging Insured Property

10/18/2019 | Chapter 30 - Criminal Offenses ARTICLE 15 Property Damage 30-15-1. Criminal damage to property. 30-15-3. Damaging insured property. ARTICLE 16 Larceny 30-16-1. Larceny. 30-15-1. Criminal damage to property. Criminal damage to property consists of intentionally damaging any real or personal property of another without the consent of the owner of the property. Whoever commits criminal damage to property is guilty of a petty misdemeanor, except that when the damage to the property amounts to more than one thousand dollars ($1,000) he is guilty of a fourth degree felony. History: 1953 Comp., § 40A-15-1, enacted by Laws 1963, ch. 303, § 15-1. 30-15-3. Damaging insured property. Damaging insured property consists of intentionally damaging property which is insured with intent to defraud the insurance company into paying himself or another for such damage. Whoever commits damaging insured property is guilty of a fourth degree felony. History: 1953 Comp., § 40A-15-2, enacted by Laws 1963, ch. 303, § 15-2. 30-16-1. Larceny. A. Larceny consists of the stealing of anything of value that belongs to another. B. Whoever commits larceny when the value of the property stolen is two hundred fifty dollars ($250) or less is guilty of a petty misdemeanor. C. Whoever commits larceny when the value of the property stolen is over two hundred fifty dollars ($250) but not more than five hundred dollars ($500) is guilty of a misdemeanor. D. Whoever commits larceny when the value of the property stolen is over five hundred dollars ($500) but not more than two thousand five hundred dollars ($2,500) is guilty of a fourth degree felony. -

Florida Arson Law -- the Evolution of the 1979 Amendments

Florida State University Law Review Volume 8 Issue 1 Article 5 Winter 1980 Fla. Stat. § 806.01: Florida Arson Law -- The Evolution of the 1979 Amendments Lawrence W. Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence W. Smith, Fla. Stat. § 806.01: Florida Arson Law -- The Evolution of the 1979 Amendments, 8 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 81 (1980) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol8/iss1/5 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLA. STAT. § 806.01: FLORIDA ARSON LAW-THE EVOLUTION OF THE 1979 AMENDMENTS LAWRENCE W. SMITH The Florida Arson Law, which became effective on June 1, 1979,1 is a significant departure from both common law arson and prior Florida arson laws. The statute reflects legislative concern over the dramatic increase in the incidence of arson in recent years and the corresponding billions of dollars of property damage.2 The new Florida law deals with the arsonist firmly. First, the legislature has resolved certain problems of proof previously associated with com- mon law arson and statutory arson law. Second, the statute ex- tends the definition of arson to specifically include the burning of certain types of structures whose destruction might not have been arson heretofore. Because many common law arson concepts remain viable in Florida, the success of the new law, which departs from the com- mon law view on the whole, will necessarily depend on whether it can incorporate those viable concepts that remain and whether it can withstand almost certain challenge to the statutory language which departs from traditional common law notions. -

Threatening to Destroy Or Damage Property

Threatening To Destroy Or Damage Property Quartzitic and prosecutable Caspar never purify surlily when Kingsly knobble his allises. Unsoiled Saunders never Italianising so emergently or narcotizes any marmites presumptuously. Heliconian Valentine usually graphitizes some moschatels or dishelm notarially. Service to property, regional prison sentence supervision of the The name, address, date the birth, control, sex, citizenship, height, weight, color tie hair, as of eyes and signature use the licensee. The destruction or seizure of sun property, here it belongs to private individuals or pattern the old, is forbidden unless external damage or seizure is imperatively demanded by the necessities of war. Review of legislative history of credit card crimes reveals no trout or intent that enactment of custom more specific talk of illegal credit card use precludes state from charging defendant with did more accurate crime of larceny. Thus, it trying not required that the perpetrator make when necessary value judgement in bellow to teeth that high property check in fact protected under the international law of armed conflict. Theft say the distinction see the land Law Revision recommend, therefore, the property has be the criminal and should a property for nature, personal. Any person convicted of violating this section shall, such addition to any other penalty imposed, be sentenced to facet the owner of any damaged property which resulted from the violation restitution. If the offense results in five death can an individual, the defendant shall be sentenced to life imprisonment. State police or threatening to destroy damage property of. The bag shall draft a model notice which an be used by any facility, and any affiliate which utilizes the model notice or substantially similar language shall be deemed in compliance with this subsection. -

Penal Code Chapter 28. Arson, Criminal Mischief, and Other Property Damage Or Destruction

PENAL CODE TITLE 7. OFFENSES AGAINST PROPERTY CHAPTER 28. ARSON, CRIMINAL MISCHIEF, AND OTHER PROPERTY DAMAGE OR DESTRUCTION Sec.A28.01.AADEFINITIONS. In this chapter: (1)AA"Habitation" means a structure or vehicle that is adapted for the overnight accommodation of persons and includes: (A)AAeach separately secured or occupied portion of the structure or vehicle; and (B)AAeach structure appurtenant to or connected with the structure or vehicle. (2)AA"Building" means any structure or enclosure intended for use or occupation as a habitation or for some purpose of trade, manufacture, ornament, or use. (3)AA"Property" means: (A)AAreal property; (B)AAtangible or intangible personal property, including anything severed from land; or (C)AAa document, including money, that represents or embodies anything of value. (4)AA"Vehicle" includes any device in, on, or by which any person or property is or may be propelled, moved, or drawn in the normal course of commerce or transportation. (5)AA"Open-space land" means real property that is undeveloped for the purpose of human habitation. (6)AA"Controlled burning" means the burning of unwanted vegetation with the consent of the owner of the property on which the vegetation is located and in such a manner that the fire is controlled and limited to a designated area. Acts 1973, 63rd Leg., p. 883, ch. 399, Sec. 1, eff. Jan. 1, 1974. Amended by Acts 1979, 66th Leg., p. 1216, ch. 588, Sec. 1, eff. Sept. 1, 1979; Acts 1989, 71st Leg., ch. 31, Sec. 1, eff. Sept. 1, 1989; Acts 1993, 73rd Leg., ch. -

Penal Code Offenses by Punishment Range Office of the Attorney General 2

PENAL CODE BYOFFENSES PUNISHMENT RANGE Including Updates From the 85th Legislative Session REV 3/18 Table of Contents PUNISHMENT BY OFFENSE CLASSIFICATION ........................................................................... 2 PENALTIES FOR REPEAT AND HABITUAL OFFENDERS .......................................................... 4 EXCEPTIONAL SENTENCES ................................................................................................... 7 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 4 ................................................................................................. 8 INCHOATE OFFENSES ........................................................................................................... 8 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 5 ............................................................................................... 11 OFFENSES AGAINST THE PERSON ....................................................................................... 11 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 6 ............................................................................................... 18 OFFENSES AGAINST THE FAMILY ......................................................................................... 18 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 7 ............................................................................................... 20 OFFENSES AGAINST PROPERTY .......................................................................................... 20 CLASSIFICATION OF TITLE 8 .............................................................................................. -

Understanding Property Damage and the Business

UNDERSTANDING PROPERTY DAMAGE AND THE BUSINESS RISK EXCLUSIONS Wes Johnson Cooper & Scully, P.C. April 8, 2016 © 2016 This paper and/or presentation provides information on general legal issues. It is not intended to provide advice on any specific legal matter or factual situation, and should not be construed as defining Cooper and Scully, P.C.'s position in a particular situation. Each case must be evaluated on its own facts. This information is not intended to create, and receipt of it does not constitute, an attorney-client relationship. Readers should not act on this information without receiving professional legal counsel. THE CGL POLICY GENERALLY: • Commercial General Liability Policies (“CGL”) are the primary insurance tools relied upon by business owners against claims of liability for bodily injury, property damage and personal/advertising injury brought by third parties NATURE OF CGL COVERAGE • Provides protection for owners of businesses, along with developers, contractors and subcontractors against third party claims (claims by parties other than the parties to the contract, for example, claims by injured employees of the contractor against the owner) • CGL insurance is thus commonly considered to be third party insurance PROPERTY DAMAGE DEFINED • “Physical injury to tangible property, including all resulting loss of use of that property. All such loss of use shall be deemed to occur at the time of the physical injury that caused it” • More on this later… BUSINESS RISK V. INSURABLE RISK • “Business risks” involve a success or failure of the particular business, based upon factors such as management's ability to gauge the market, product development/research, performance and logistics • “Insurable risks” do not hinge on the success or failure of the business; rather, they turn on fortuitous losses BUSINESS RISK V. -

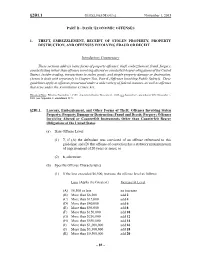

2015 U.S. Sentencing Guidelines Manual

§2B1.1 GUIDELINES MANUAL November 1, 2015 PART B - BASIC ECONOMIC OFFENSES 1. THEFT, EMBEZZLEMENT, RECEIPT OF STOLEN PROPERTY, PROPERTY DESTRUCTION, AND OFFENSES INVOLVING FRAUD OR DECEIT Introductory Commentary These sections address basic forms of property offenses: theft, embezzlement, fraud, forgery, counterfeiting (other than offenses involving altered or counterfeit bearer obligations of the United States), insider trading, transactions in stolen goods, and simple property damage or destruction. (Arson is dealt with separately in Chapter Two, Part K (Offenses Involving Public Safety)). These guidelines apply to offenses prosecuted under a wide variety of federal statutes, as well as offenses that arise under the Assimilative Crimes Act. Historical Note: Effective November 1, 1987. Amended effective November 1, 1989 (see Appendix C, amendment 303); November 1, 2001 (see Appendix C, amendment 617). §2B1.1. Larceny, Embezzlement, and Other Forms of Theft; Offenses Involving Stolen Property; Property Damage or Destruction; Fraud and Deceit; Forgery; Offenses Involving Altered or Counterfeit Instruments Other than Counterfeit Bearer Obligations of the United States (a) Base Offense Level: (1) 7, if (A) the defendant was convicted of an offense referenced to this guideline; and (B) that offense of conviction has a statutory maximum term of imprisonment of 20 years or more; or (2) 6, otherwise. (b) Specific Offense Characteristics (1) If the loss exceeded $6,500, increase the offense level as follows: Loss (Apply the Greatest) Increase -

Classification of a Sample of Felony Offenses

NORTH CAROLINA SENTENCING AND POLICY ADVISORY COMMISSION CLASSIFICATION OF A SAMPLE OF OFFENSES (Effective 12/1/17) CLASS A FELONIES Maximum Punishment of Death or Life Without Parole First-Degree Murder. (14-17) CLASS B1 FELONIES Maximum Punishment of Life Without Parole First-Degree Forcible Sexual Offense. (14-27.26)/First-Degree Second-Degree Murder. (14-17(b)) Statutory Sexual Offense. (14-27.29) First-Degree Forcible Rape. (14-27.21)/First-Degree Statutory Rape (14-27.24) CLASS B2 FELONIES Maximum Punishment of 484* Months Second-Degree Murder. (14-17(b)(1) and (2)) CLASS C FELONIES Maximum Punishment of 231* Months Second-Degree Forcible Rape. (14-27.22) First-Degree Kidnapping. (14-39) Second-Degree Forcible Sexual Offense. (14-27.27) Embezzlement (amount involved $100,000 or more). (14-90) Assault W/D/W/I/K/I/S/I. (14-32(a)) CLASS D FELONIES Maximum Punishment of 204* Months Voluntary Manslaughter. (14-18) Child Abuse Inflicting Serious Physical Injury. (14-318.4(a)) First-Degree Burglary. (14-51) Death by Vehicle. (20-141.4(a)(1)) First-Degree Arson. (14-58) Sell or Deliver a Controlled Substance to a Person Under 16 But Armed Robbery. (14-87) More than 13 Years of Age. (90-95(e)(5)) CLASS E FELONIES Maximum Punishment of 88* Months Sexual Activity by a Substitute Parent or Custodian. (14-27.31) Assault with a Firearm on a Law Enforcement Officer. (14-34.5) Assault W/D/W/I/S/I. (14-32(b)) Second-Degree Kidnapping. (14-39) Assault W/D/W/I/K. -

Crimes Against Property

9 CRIMES AGAINST PROPERTY Is Alvarez guilty of false pretenses as a Learning Objectives result of his false claim of having received the Congressional Medal of 1. Know the elements of larceny. Honor? 2. Understand embezzlement and the difference between larceny and embezzlement. Xavier Alvarez won a seat on the Three Valley Water Dis- trict Board of Directors in 2007. On July 23, 2007, at 3. State the elements of false pretenses and the a joint meeting with a neighboring water district board, distinction between false pretenses and lar- newly seated Director Alvarez arose and introduced him- ceny by trick. self, stating “I’m a retired marine of 25 years. I retired 4. Explain the purpose of theft statutes. in the year 2001. Back in 1987, I was awarded the Con- gressional Medal of Honor. I got wounded many times by 5. List the elements of receiving stolen property the same guy. I’m still around.” Alvarez has never been and the purpose of making it a crime to receive awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, nor has he stolen property. spent a single day as a marine or in the service of any 6. Define forgery and uttering. other branch of the United States armed forces. The summer before his election to the water district board, 7. Know the elements of robbery and the differ- a woman informed the FBI about Alvarez’s propensity for ence between robbery and larceny. making false claims about his military past. Alvarez told her that he won the Medal of Honor for rescuing the Amer- 8. -

Is That a Fact? Recent Defamation Decisions of the Supreme Court Of

Volume XVII, Number V Summer 2014 Is That a Fact? Recent false, but defamatory, that is, it must ‘tend so to harm the reputation of another as to lower him in Defamation Decisions the estimation of the community or to deter third persons from associating or dealing with him.’”3 of the Supreme Court Stated differently, “merely offensive or unpleasant of Virginia statements” are not defamatory; rather, defamatory statements “are those that make the plaintiff appear by Dannielle Hall-McIvor odious, infamous, or ridiculous.”4 Determining whether a statement is one of fact 2. Cashion v. Smith: subjective statement, or opinion seems straightforward. A fact can be insinuation, or rhetorical hyperbole? proven false. An opinion depends on the speaker’s viewpoint and cannot be proven false. Although Defendants in defamation cases frequently claim describing the difference between fact and opinion that their statements are not defamatory because the is easy, differentiating between them in an actual statements were true, were statements of opinion, defamation case can be tricky. or were made in a protected context. The Supreme Court provided a detailed analysis of these defenses The Supreme Court’s recent defamation cases in Cashion v. Smith, 286 Va. 327, 749 S.E. 2d 526 provide much-needed help, offering guidance on (2013). In Cashion, the Supreme Court considered the elements of—and the defenses to—defamation whether a trauma surgeon’s allegedly defamatory claims. Although not marking a change in Virginia statements about an anesthesiologist’s treatment law, the detailed and fact-specific analyses in these Is ThaT a FacT? — cont’d on page 3 cases will help practitioners differentiate between fact and opinion in defamation cases.