Arxiv:2107.12590V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 3 Aug 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The British Astronomical Association Handbook 2017

THE HANDBOOK OF THE BRITISH ASTRONOMICAL ASSOCIATION 2017 2016 October ISSN 0068–130–X CONTENTS PREFACE . 2 HIGHLIGHTS FOR 2017 . 3 CALENDAR 2017 . 4 SKY DIARY . .. 5-6 SUN . 7-9 ECLIPSES . 10-15 APPEARANCE OF PLANETS . 16 VISIBILITY OF PLANETS . 17 RISING AND SETTING OF THE PLANETS IN LATITUDES 52°N AND 35°S . 18-19 PLANETS – EXPLANATION OF TABLES . 20 ELEMENTS OF PLANETARY ORBITS . 21 MERCURY . 22-23 VENUS . 24 EARTH . 25 MOON . 25 LUNAR LIBRATION . 26 MOONRISE AND MOONSET . 27-31 SUN’S SELENOGRAPHIC COLONGITUDE . 32 LUNAR OCCULTATIONS . 33-39 GRAZING LUNAR OCCULTATIONS . 40-41 MARS . 42-43 ASTEROIDS . 44 ASTEROID EPHEMERIDES . 45-50 ASTEROID OCCULTATIONS .. ... 51-53 ASTEROIDS: FAVOURABLE OBSERVING OPPORTUNITIES . 54-56 NEO CLOSE APPROACHES TO EARTH . 57 JUPITER . .. 58-62 SATELLITES OF JUPITER . .. 62-66 JUPITER ECLIPSES, OCCULTATIONS AND TRANSITS . 67-76 SATURN . 77-80 SATELLITES OF SATURN . 81-84 URANUS . 85 NEPTUNE . 86 TRANS–NEPTUNIAN & SCATTERED-DISK OBJECTS . 87 DWARF PLANETS . 88-91 COMETS . 92-96 METEOR DIARY . 97-99 VARIABLE STARS (RZ Cassiopeiae; Algol; λ Tauri) . 100-101 MIRA STARS . 102 VARIABLE STAR OF THE YEAR (T Cassiopeiæ) . .. 103-105 EPHEMERIDES OF VISUAL BINARY STARS . 106-107 BRIGHT STARS . 108 ACTIVE GALAXIES . 109 TIME . 110-111 ASTRONOMICAL AND PHYSICAL CONSTANTS . 112-113 INTERNET RESOURCES . 114-115 GREEK ALPHABET . 115 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS / ERRATA . 116 Front Cover: Northern Lights - taken from Mount Storsteinen, near Tromsø, on 2007 February 14. A great effort taking a 13 second exposure in a wind chill of -21C (Pete Lawrence) British Astronomical Association HANDBOOK FOR 2017 NINETY–SIXTH YEAR OF PUBLICATION BURLINGTON HOUSE, PICCADILLY, LONDON, W1J 0DU Telephone 020 7734 4145 PREFACE Welcome to the 96th Handbook of the British Astronomical Association. -

Ice& Stone 2020

Ice & Stone 2020 WEEK 51: DECEMBER 13-19 Presented by The Earthrise Institute # 51 Authored by Alan Hale COMET OF THE WEEK: The Great Comet of 1680 Perihelion: 1680 December 18.49, q = 0.006 AU The Great Comet of 1680 over Rotterdam in The Netherlands, during late December 1680 as painted by the Dutch artist Lieve Verschuier. This particular comet was undoubtedly one of the brightest comets of the 17th Century, but it is also one of the most important comets in history from a scientific perspective, and perhaps even from the perspective of overall human history. While there were certainly plenty of superstitions attached to the comet’s appearance, the scientific investigations made of it were among the beginnings of the era in European history we now call The Enlightenment, and indeed, in a sense the Great Comet of 1680 can perhaps be considered as one of the sparks of that era. The significance began with the comet’s discovery, which was made on the morning of November 14, 1680, by a German astronomer residing in Coburg, Gottfried Kirch – the first comet ever to be discovered by means of a telescope. It was already around 4th magnitude at that time, and located near the star Regulus in the constellation Leo; from that point it traveled eastward and brightened rapidly, being closest to Earth (0.42 AU) on November 30. By that time it was a conspicuous naked-eye object with a tail 20 to 30 degrees long, and it remained visible for another week before disappearing into morning twilight. -

Asteroid Regolith Weathering: a Large-Scale Observational Investigation

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2019 Asteroid Regolith Weathering: A Large-Scale Observational Investigation Eric Michael MacLennan University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation MacLennan, Eric Michael, "Asteroid Regolith Weathering: A Large-Scale Observational Investigation. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2019. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5467 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Eric Michael MacLennan entitled "Asteroid Regolith Weathering: A Large-Scale Observational Investigation." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Geology. Joshua P. Emery, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Jeffrey E. Moersch, Harry Y. McSween Jr., Liem T. Tran Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Asteroid Regolith Weathering: A Large-Scale Observational Investigation A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Eric Michael MacLennan May 2019 © by Eric Michael MacLennan, 2019 All Rights Reserved. -

Accurate Positions of Pluto and Asteroids Observed in Bucharest During the Year 1932

ACCURATE POSITIONS OF PLUTO AND ASTEROIDS OBSERVED IN BUCHAREST DURING THE YEAR 1932 GHEORGHE BOCŞA, PETRE POPESCU, MIHAELA LICULESCU Astronomical Institute of the Romanian Academy Str. Cuţitul de Argint 5, 040557 Bucharest, Romania E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The paper contains the observations of minor planets performed in Bucharest Astronomical Observatory in the year 1932 with the 380/6000 mm astrograph. Both Turner’s (constants) and Schlesinger’s (dependences) methods were used in the computation of the normal coordinates of the objects. Keywords: photographic astrometry – minor planets. 1. INTRODUCTION The article is a continuation of the complete investigation of Bucharest Wide-Field Plates Archive initiated in 2010; it contains the plates with asteroids observed in 1932. That year 185 plates were exposed and were stored in the archive, but were not reduced. After analysing them, 98 plates were detected to contain measurable minor planets. The first observed positions in this year were of planet Pluto. They were exposed on 1318cm plates, with 52 minutes exposure .The observations were performed by the famous Romanian astronomer Professor Gheorghe Demetrescu. The most difficult problem was the identification of the planet, the three plates obtained in 1932 having dozens of stars with up to 15 magnitudes. As all the observations were performed in the same month and the planet did not have a great proper motion, it was possible to superpose two plates and to identify Pluto. The values (O–C)α and (O–C)δ were calculated by M. Svechnikov from the Institute of Applied Astronomy in Sankt Petersburg on the basis of precise positions obtained in Bucharest, which we integrated in Pluto’s orbit. -

Appendix 1 1311 Discoverers in Alphabetical Order

Appendix 1 1311 Discoverers in Alphabetical Order Abe, H. 28 (8) 1993-1999 Bernstein, G. 1 1998 Abe, M. 1 (1) 1994 Bettelheim, E. 1 (1) 2000 Abraham, M. 3 (3) 1999 Bickel, W. 443 1995-2010 Aikman, G. C. L. 4 1994-1998 Biggs, J. 1 2001 Akiyama, M. 16 (10) 1989-1999 Bigourdan, G. 1 1894 Albitskij, V. A. 10 1923-1925 Billings, G. W. 6 1999 Aldering, G. 4 1982 Binzel, R. P. 3 1987-1990 Alikoski, H. 13 1938-1953 Birkle, K. 8 (8) 1989-1993 Allen, E. J. 1 2004 Birtwhistle, P. 56 2003-2009 Allen, L. 2 2004 Blasco, M. 5 (1) 1996-2000 Alu, J. 24 (13) 1987-1993 Block, A. 1 2000 Amburgey, L. L. 2 1997-2000 Boattini, A. 237 (224) 1977-2006 Andrews, A. D. 1 1965 Boehnhardt, H. 1 (1) 1993 Antal, M. 17 1971-1988 Boeker, A. 1 (1) 2002 Antolini, P. 4 (3) 1994-1996 Boeuf, M. 12 1998-2000 Antonini, P. 35 1997-1999 Boffin, H. M. J. 10 (2) 1999-2001 Aoki, M. 2 1996-1997 Bohrmann, A. 9 1936-1938 Apitzsch, R. 43 2004-2009 Boles, T. 1 2002 Arai, M. 45 (45) 1988-1991 Bonomi, R. 1 (1) 1995 Araki, H. 2 (2) 1994 Borgman, D. 1 (1) 2004 Arend, S. 51 1929-1961 B¨orngen, F. 535 (231) 1961-1995 Armstrong, C. 1 (1) 1997 Borrelly, A. 19 1866-1894 Armstrong, M. 2 (1) 1997-1998 Bourban, G. 1 (1) 2005 Asami, A. 7 1997-1999 Bourgeois, P. 1 1929 Asher, D. -

(2000) Forging Asteroid-Meteorite Relationships Through Reflectance

Forging Asteroid-Meteorite Relationships through Reflectance Spectroscopy by Thomas H. Burbine Jr. B.S. Physics Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 1988 M.S. Geology and Planetary Science University of Pittsburgh, 1991 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF EARTH, ATMOSPHERIC, AND PLANETARY SCIENCES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN PLANETARY SCIENCES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY FEBRUARY 2000 © 2000 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Signature of Author: Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences December 30, 1999 Certified by: Richard P. Binzel Professor of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Ronald G. Prinn MASSACHUSES INSTMUTE Professor of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences Department Head JA N 0 1 2000 ARCHIVES LIBRARIES I 3 Forging Asteroid-Meteorite Relationships through Reflectance Spectroscopy by Thomas H. Burbine Jr. Submitted to the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences on December 30, 1999 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Planetary Sciences ABSTRACT Near-infrared spectra (-0.90 to ~1.65 microns) were obtained for 196 main-belt and near-Earth asteroids to determine plausible meteorite parent bodies. These spectra, when coupled with previously obtained visible data, allow for a better determination of asteroid mineralogies. Over half of the observed objects have estimated diameters less than 20 k-m. Many important results were obtained concerning the compositional structure of the asteroid belt. A number of small objects near asteroid 4 Vesta were found to have near-infrared spectra similar to the eucrite and howardite meteorites, which are believed to be derived from Vesta. -

Taxonomic Classification of Asteroids Based on MOVIS Near-Infrared Colors

A&A 617, A12 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201833023 Astronomy & © ESO 2018 Astrophysics Taxonomic classification of asteroids based on MOVIS near-infrared colors? M. Popescu1,2,3, J. Licandro1,2, J. M. Carvano4, R. Stoicescu3, J. de León1,2, D. Morate1,2, I. L. Boaca˘3, and C. P. Cristescu5 1 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC), C/Vía Láctea s/n, 38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 2 Departamento de Astrofísica, Universidad de La Laguna, 38206 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain e-mail: [email protected] 3 Astronomical Institute of the Romanian Academy, 5 Cu¸titulde Argint, 040557 Bucharest, Romania 4 Observatório Nacional, rua Gal. José Cristino 77, São Cristóvão, 20921-400 Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 5 Department of Physics, University Politehnica of Bucharest, Bucure¸sti 060042, Romania Received 14 March 2018 / Accepted 14 June 2018 ABSTRACT Context. The MOVIS catalog contains the largest set of near-infrared (NIR) colors for solar system objects. These data were obtained from the observations performed by VISTA-VHS survey using the Y, J, H, and Ks filters. The taxonomic classification of objects in this catalog allows us to obtain large-scale distributions for the asteroidal population, to study faint objects, and to select targets for detailed spectral investigations. Aims. We aim to provide a taxonomic classification for asteroids observed by VISTA-VHS survey. We derive a method for assigning a compositional type to an object based on its (Y − J), (J − Ks), and (H − Ks) colors. Methods. We present a taxonomic classification for 18 265 asteroids from the MOVIS catalog, using a probabilistic method and the k-nearest neighbors algorithm. -

Spin States of Asteroids in the Eos Collisional Family

Spin states of asteroids in the Eos collisional family J. Hanuša,∗, M. Delbo’b, V. Alí-Lagoac, B. Bolinb, R. Jedicked, J. Durechˇ a, H. Cibulkováa, P. Pravece, P. Kušniráke, R. Behrendf, F. Marchisg, P. Antoninih, L. Arnoldi, M. Audejeanj, M. Bachschmidti, L. Bernasconik, L. Brunettol, S. Casullim, R. Dymockn, N. Esseivao, M. Estebanp, O. Gerteisi, H. de Grootq, H. Gullyi, H. Hamanowar, H. Hamanowar, P. Kraffti, M. Lehkýa, F. Manzinis, J. Michelett, E. Morelleu, J. Oeyv, F. Pilcherw, F. Reignierx, R. Royy, P.A. Salomp, B.D. Warnerz aAstronomical Institute, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Charles University, V Holešoviˇckách 2, 18000 Prague, Czech Republic bUniversité Côte d’Azur, OCA, CNRS, Lagrange, France cMax-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik, Giessenbachstraße, Postfach 1312, 85741 Garching, Germany dInstitute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA eAstronomical Institute, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Friˇcova 1, CZ-25165 Ondˇrejov, Czech Republic fGeneva Observatory, CH-1290 Sauverny, Switzerland gSETI Institute, Carl Sagan Center, 189 Bernado Avenue, Mountain View CA 94043, USA hObservatoire des Hauts Patys, F-84410 Bédoin, France iAix Marseille Université, CNRS, OHP (Observatoire de Haute Provence), Institut Pythéas (UMS 3470) 04870 Saint-Michel-l’Observatoire, France jObservatoire de Chinon, Mairie de Chinon, 37500 Chinon, France kObservatoire des Engarouines, 1606 chemin de Rigoy, F-84570 Malemort-du-Comtat, France lLe Florian, Villa 4, 880 chemin de Ribac-Estagnol, -

Constraining Meteorite Analogs for the Eos Dynamical Family Via Mineralogical Band Analysis

42nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2011) 2184.pdf CONSTRAINING METEORITE ANALOGS FOR THE EOS DYNAMICAL FAMILY VIA MINERALOGICAL BAND ANALYSIS. P. S. Hardersen1, T. Mothe’-Diniz2, and E. A. Cloutis3. 1University of North Dakota, Department of Space Studies, 4149 University Avenue, 530 Clifford Hall, Box 9008, Grand Forks, ND 58202, [email protected], 2Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro/Observatorio do Valongo, Lad. Pedro Antonio, 43-20080-090 Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, [email protected]. 3Department of Geography, University of Winnipeg, Winnipeg, MB R3B 2E9. Introduction: The Eos dynamical family was Two Eos family asteroids in [8] and two additional classified by [1] and is located in the main asteroid belt asteroids in [7] display Band I features only. Table 2 beyond the 5:2 mean-motion resonance. The archetype below shows the derived Band I centers for these as- of the family, 221 Eos, has a = 3.01AU, i = 10.9°, and teroids. e = 0.105. This asteroid family includes 202 members Table 2: according to [1]. Early work by [2] suggested that Eos family members were populated by S-type asteroids, Asteroid Band I (µm) but more recent work by [3] analyzing visible-λ spectra 766 Moguntia 1.068 ± 0.004 suggested compositional diversity, evidence for space 798 Ruth 1.056 ± 0.004 weathering, and possible affinities to the CO and CV 1903 Adzhimushkaj 1.049 ± 0.003 chondrites for the Eos family. [4] and [5] have exam- 2957 Tatsuo 1.044 ± 0.003 ined collisional and dynamical evolution of the Eos family with [4] identifying likely Eos family members Methodology: This work will conduct band center in the 9:4 mean-motion resonance. -

Main-Belt Asteroids with Wise/Neowise: Near-Infrared Albedos

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Caltech Authors The Astrophysical Journal, 791:121 (11pp), 2014 August 20 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/791/2/121 C 2014. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. MAIN-BELT ASTEROIDS WITH WISE/NEOWISE: NEAR-INFRARED ALBEDOS Joseph R. Masiero1, T. Grav2, A. K. Mainzer1,C.R.Nugent1,J.M.Bauer1,3, R. Stevenson1, and S. Sonnett1 1 Jet Propulsion Laboratory/Caltech, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, MS 183-601, Pasadena, CA 91109, USA; [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 2 Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, AZ, USA; [email protected] 3 Infrared Processing and Analysis Center, Caltech, Pasadena, CA, USA Received 2014 May 14; accepted 2014 June 25; published 2014 August 6 ABSTRACT We present revised near-infrared albedo fits of 2835 main-belt asteroids observed by WISE/NEOWISE over the course of its fully cryogenic survey in 2010. These fits are derived from reflected-light near-infrared images taken simultaneously with thermal emission measurements, allowing for more accurate measurements of the near- infrared albedos than is possible for visible albedo measurements. Because our sample requires reflected light measurements, it undersamples small, low-albedo asteroids, as well as those with blue spectral slopes across the wavelengths investigated. We find that the main belt separates into three distinct groups of 6%, 16%, and 40% reflectance at 3.4 μm. -

Broadband Photometry of the Potentially Hazardous Asteroid (153958) 2002 AM31: a Binary Near-Earth Asteroid

Broadband Photometry of the Potentially Hazardous Asteroid (153958) 2002 AM31: A Binary Near-Earth Asteroid Tamara Davtyan¹, Michael D Hicks² 1-Los Angeles City College, Los Angeles, CA 2-Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, CA Abstract The near-Earth asteroid 153958 (2002 AM31) was discovered on January 14, 2002 by the LINEAR NEO survey (MPEC 2002-A102) in New Mexico. The object passed within 0.035 AU of the Earth on July 22 2012 and has been identified as a Potentially Hazardous Asteroid (PHA) by the IAU Minor Planet Center. We were motivated by the PHA's favorable 2012 apparition and obtained 6 nights of time-resolved Bessel BVRI photometry and 5 nights of Bessel R photometry at the JPL Table Mountain Observatory (TMO) 0.6-m telescope. We generated a solar phase curve that was used to fit a standard H-G model ( H R=18.43, G=0.61). The derived G value was found to indicate a high optical albedo and an E-type classification. However, our observations yielded that the object's averaged broad-band colors indices ( B− R=0.217±0.018 mag; V −R=0.066±0.010 mag, R− I=0.001±0.110 mag) were most compatible with an S-type spectral classification (Bus taxonomy). This association obtained through a comparison with the 1341 asteroid spectra collected by SMASS 2 survey (Bus & Binzel 2002) and was best matched by the S-type asteroid 485 Genua. If we adopt a diameter of 0.34 km obtained by Arecibo radar imaging, then we estimate geometric albedo p=0.61. -

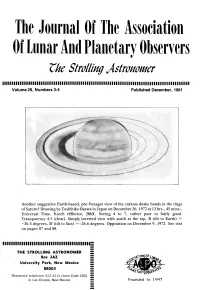

The Journal of the Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers C::Lte Strolling Astronomer

The Journal Of The Association Of Lunar And Planetary Observers C::lte Strolling Astronomer 11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 Volume 29, Numbers 3-4 Published December, 1981 Another suggestive Earth-based, pre-Voyager view ofthe curious dusky bands in the rings of Saturn? Drawing by Toshihiko Osawa in Japan on December 26, 1972 at 13 hrs., 45 mins., Universal Time. 8-inch reflector, 286X. Seeing 4 to 7, rather poor to fairly good. Transparency 4.5 (clear). Simply inverted view with south at the top. B (tilt to Earth) = -26.4 degrees. B' (tilt to Sun) = -26.6 degrees. Opposition on December 9, 1972. See text on pages 87 and 88. !1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111=- THE STROLLING ASTRONOMER - Box 3AZ - University Park, New Mexico - 88003 - Res1dence telephone 522·4213 (Area Code 505) - in Las Cruces, New Mexico - Founded In 1947 INTIDSISSUE mE APPARITION OF COMET BRADFIELD 1979 X, by Stephen J. O'Meara and Daniel W. E. Green ......................... pg. 45 WHAT IS NEW ON MARS-MARTIAN 1979-1980 APPARITION REPORT ll (Concluded), by C. F. Capen and D. C. Parker ...................................... pg. 51 mE 1981 A.L.P.O. BUSINESS MEETING, by Phillip W. Budine and Julius L. Benton, Jr. ......................... pg. 60 AMATEURS AMONG THE ASTEROIDS, by J. U. Gunter ......................................•.............. pg. 61 mE MINOR PLANETS: AS INTERESTING AS EVER, by Alain Porter ..................................................... pg. 64 COMET WEST 1976 VI: OBSERVATIONS OF THE GREAT COMET OF 1976, by Derek W allentinsen .............................................. pg. 69 BOOK REVIEWS ........................•.......................... pg. 79 NEW BOOKS RECEIVED, by J. Russell Smith and Charles S. Morris .............................• pg. 83 THE A.L.P.O. AT ASTROCON '81, by Don Parker and Jeff Beish ........................................