Racing for Fans: Communication Technology, the Total Experience, and the Rise of Nascar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download "FEB TOY AUCTION.Pdf"

John Carl Auction Company 8 W Elizabeth St. Maytown, PA 17550 Phone: 717-618-9727 FEBRUARY ONLINE ONLY TOY AUCTION 2/5/2020-2/23/2020 LOT # QTY LOT # QTY 1 Racing Champions 1:24 Replica Car 1 19 Winner's Circle 1:24 Replica Car 1 #9 Northern Light. NASCAR 2000 series. Die cast. #3 Nilla Wafers. Dale Earnhardt Jr. 2001. 2 Hotwheels Racing 1:24 Replica Car 1 20 Winner's Circle 1:24 Replica Car 1 #99 Excide. Jeff Burton. 2000 Edition. #29 GM Goodwrench. Kevin Harwick. 2001 3 Racing Champions 1:24 Replica Car 1 21 Winner's Circle 1:24 Replica Car 1 #9 Track Gear. Jeff Burton. Signature Drivers Series. #29 GM Goodwrench. Kevin Harwick. 2001 4 Team Caliber Pit Stop 1:24 Replica Car 1 22 Team Caliber Pit Stop 1:24 Replica Car 1 #99 Velveeta. Jeff Burton. 2003 Series. Die Cast. #99 Velveeta. Jeff Burton. 2003 Series. Die Cast. 5 Hotwheels Racing 1:24 Replica Car 1 23 Hotwheels Racing 1:24 Replica Car 1 #99 Citgo. Jeff Burton. 2002 Series. #99 Citgo. Jeff Burton. Stock Car Series. 6 Hotwheels Racing 1:24 Replica Car 1 24 Winner's Circle 1:24 Replica Car 1 #99 Citgo. Jeff Burton. 2001 Series. #12 Supercuts. Kerry Earnhardt. 2002 7 Racing Champions 1:24 Replica Car 1 25 Team Caliber Pit Stop 1:24 Replica Car 1 #99 Excide. Jeff Burton. 1999. Under the Lights Finish. #99 Citgo. Jeff Burton. 2002 Series. Die cast. 8 Hotwheels Racing 1:24 Replica Car 1 26 Racing Champions 1:24 Replica Car 1 #99 Excide. -

Motorcycling

11:00am - NASCAR Hall Click To Login Or Register Search keywords, programs, or site HomePhotos TVVideos ShowsPodcastTV ScheduleMobile NASCAR Formula 1 Auto Racing Moto Racing Cars Bikes Store Community Games of Fame Vote (HD) Lifestyle New Models Destinations Gearbag In The News Archive Suzuki Summer Cruise Test Ride: Kawasaki Ninja GEARBAG: Endurance, by Theresa Ortolani Author: GEARBAG: Endurance, by Theresa Written by: SPEED Staff SPEED Staff Ortolani SPEEDtv.com GEARBAG: Pirelli Angel ST: Discover 10/12/2009 Your Inner Spirit Charlotte. NC Profile Contact Login For More GEARBAG: New Sceamin' Eagle Nightstick Diffuser Disc Muffler Signed copies of GEARBAG: Hugger Gloves ENDURANCE are available for purchase GEARBAG: Shark Evoline Helmet directly from the author Rate this article: at a discounted rate. GEARBAG: SOHO Gore-Tex® Boot Pre-order before the book is released and GEARBAG: Roaring Toyz OSD 330 receive an 8.5 x 11” With Performance Machine 330 Gicleé print. Wheels… bikes GEARBAG: The S Plug Canal Phones In an age where many books high-adrenaline sports Ortolani applies an artist’s eye to this unforgiving BIKES: Öhlins USA Technicians At have become watered- sport and the riders who pursue it. » More bookstore Transworld Motocross Dirt Days… down exercises in Photos GEARBAG: New Harley-Davidson marketing, dirt bike Zeppelin® Touring Seat racing remains intensely GEARBAG: Aerostich Accessory Mount raw; a dangerous enterprise populated with a colorful, profane cast of daredevils. Ortolani applies an artist’s eye to this unforgiving sport and the riders who pursue it, resulting in an unprecedented, behind-the- GEARBAG: Can-Am RT‐622 Trailer, Hitch Kit, And Control Module… scenes window into this punishing competition. -

Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M

April 17 - 23, 2009 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey Å 4 News (N) Å CBS Evening News (N) Å Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Save Our Flashpoint “First in Line” ’ NUMB3RS “Jack of All Trades” News (N) Å (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight Souls” ’ Å 4 Å 4 ’ Å 4 Letterman (N) ’ 4 KJZZ 3The People’s Court (N) 4 The Insider 4 Frasier ’ 4 Friends ’ 4 Friends 5 Fortune Jeopardy! 3 Dr. Phil ’ Å 4 News (N) Å Scrubs ’ 5 Scrubs ’ 5 Entertain The Insider 4 The Ellen DeGeneres Show (N) News (N) World News- News (N) Two and a Half Wife Swap “Burroughs/Padovan- Supernanny “DeMello Family” 20/20 ’ Å 4 News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4’ Å 3 Gibson Men 5 Hickman” (N) ’ 4 (N) ’ Å line (N) 3 wood (N) 4 (N) Å 4 News (N) Å News (N) Å News (N) Å NBC Nightly News (N) Å News (N) Å Howie Do It Howie Do It Dateline NBC A police of cer looks into the disappearance of a News (N) Å (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night- KSL 5 News (N) 3 (N) ’ Å (N) ’ Å Michigan woman. (N) ’ Å Jay Leno ’ Å 5 Jimmy Fallon TBS 6Raymond Friends ’ 5 Seinfeld ’ 4 Seinfeld ’ 4 Family Guy 5 Family Guy 5 ‘Happy Gilmore’ (PG-13, ’96) ›› Adam Sandler. -

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64 An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by James R. McAleese Janelle Knight Edward Matava Matthew Hurlbut-Coke Date: 22nd March 2021 Report Submitted to: Professor Dean O’Donnell Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. Abstract This project was an attempt to expand and document the Gordon Library’s Video Game Archive more specifically, the Nintendo 64 (N64) collection. We made the N64 and related accessories and games more accessible to the WPI community and created an exhibition on The History of 3D Games and Twitch Plays Paper Mario, featuring the N64. 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Table of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………………5 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 1-Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 2-Background………………………………………………………………………………………… . 11 2.1 - A Brief of History of Nintendo Co., Ltd. Prior to the Release of the N64 in 1996:……………. 11 2.2 - The Console and its Competitors:………………………………………………………………. 16 Development of the Console……………………………………………………………………...16 -

Danica Patrick, Dale Earnha

Danica Patrick, Dale Earnhardt, Jr. fans of iRacing simulation - Bruce Martin - SI.com http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/2009/writers/bruce_martin/12/21/iracing/index.html EXTRA MUSTARD FANNATION VAULT FANTASY DAN PATRICK SWIMSUIT PHOTOS SI KIDS VIDEO ACTION SPORTS MAXPREPS SPORTSMAN NFL COLLEGE FOOTBALL MLB NBA COLLEGE BB GOLF NHL RACING SOCCER MMA & BOXING HIGH SCHOOL TENNIS MORE Posted: Monday December 21, 2009 3:09PM; Updated: Monday December 21, 2009 7:56PM More Columns Story Highlights iRacing has worked to insure that its users’ experience mirrors real life Danica Patrick, Dale Earnhardt Jr., Justin Wilson are members of iRacing iRacing costs its 15,000 users less than eight dollars per month PRINT EMAIL BUZZ FACEBOOK DIGG TWITTER RSS SHARE MOORESVILLE, N.C. -- With just a few days left until Christmas, shoppers are scurrying through the snow and ice to find the perfect gift for the holidays. Race fans need not worry; iRacing has the answer: a subscription to iRacing Motorsports Simulations, which allows members the chance to race against NASCAR's Dale Earnhardt Jr. and A.J. Allmendinger as well as IndyCar Series drivers Justin Wilson and Danica Patrick. iRacing Motorsports Simulations isn't a game -- it's a The iRacing simulation is so real that bumps totally unique interactive racing simulation that is on the track mirror those in real life. iRacing.com available for a subscription price of $99 per year, which works out to less than $8 per month. The computer SI.com on simulation of each track is so realistic that the users often think they are watching a NASCAR or IndyCar Series UPCOMING POPULAR race in high-definition. -

NASCAR for Dummies (ISBN

spine=.672” Sports/Motor Sports ™ Making Everything Easier! 3rd Edition Now updated! Your authoritative guide to NASCAR — 3rd Edition on and off the track Open the book and find: ® Want to have the supreme NASCAR experience? Whether • Top driver Mark Martin’s personal NASCAR you’re new to this exciting sport or a longtime fan, this insights into the sport insider’s guide covers everything you want to know in • The lowdown on each NASCAR detail — from the anatomy of a stock car to the strategies track used by top drivers in the NASCAR Sprint Cup Series. • Why drivers are true athletes NASCAR • What’s new with NASCAR? — get the latest on the new racing rules, teams, drivers, car designs, and safety requirements • Explanations of NASCAR lingo • A crash course in stock-car racing — meet the teams and • How to win a race (it’s more than sponsors, understand the different NASCAR series, and find out just driving fast!) how drivers get started in the racing business • What happens during a pit stop • Take a test drive — explore a stock car inside and out, learn the • How to fit in with a NASCAR crowd rules of the track, and work with the race team • Understand the driver’s world — get inside a driver’s head and • Ten can’t-miss races of the year ® see what happens before, during, and after a race • NASCAR statistics, race car • Keep track of NASCAR events — from the stands or the comfort numbers, and milestones of home, follow the sport and get the most out of each race Go to dummies.com® for more! Learn to: • Identify the teams, drivers, and cars • Follow all the latest rules and regulations • Understand the top driver skills and racing strategies • Have the ultimate fan experience, at home or at the track Mark Martin burst onto the NASCAR scene in 1981 $21.99 US / $25.99 CN / £14.99 UK after earning four American Speed Association championships, and has been winning races and ISBN 978-0-470-43068-2 setting records ever since. -

NASCAR for Dummies, 3Rd Edition

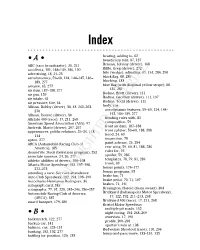

Index bearing, adding to, 62 • A • benefi ciary rule, 87, 137 ABC (race broadcaster), 20, 251 Benson, Johnny (driver), 168 accidents, 101, 148–149, 186, 190 Biffl e, Greg (driver), 272 advertising, 18, 24–25 bite (wedge), adjusting, 67, 154, 286, 290 aerodynamics, 59–60, 124, 144–145, 186– black fl ag, 88, 280 189, 277 blocking, 133 a-frame, 65, 277 blue fl ag (with diagonal yellow stripe), 88, air dam, 187–188, 277 135, 281 air gun, 159 Bodine, Brett (driver), 111 air intake, 61 Bodine, Geoffrey (driver), 111, 197 air pressure, tire, 64 Bodine, Todd (driver), 111 Allison, Bobby (driver), 30, 43, 262–263, body, car 270 aerodynamic features, 59–60, 124, 144– Allison, Donnie (driver), 30 145, 186–189, 277 Allstate 400 (race), 17, 211, 268 bending rules with, 85 American Speed Association (ASA), 97 composition, 59 Andretti, Mario (driver), 207, 267 front air dam, 187–188 appearances, public relations, 25–26, 113, front splitter, 59–60, 188, 288 114 hood, 24, 69 apron, 277 inspection, 78 ARCA (Automobile Racing Club of paint scheme, 25, 284 America), 185 rear wing, 59, 60, 81, 188, 286 Around the Track (television program), 252 rules for, 76 associate sponsor, 24, 26, 277 spoiler, 59, 286 athletic abilities of drivers, 106–108 templates, 78, 79, 81, 289 Atlanta Motor Speedway, 192, 197–198, trunk, 69 272–273 bonus points, 176–177 attending a race. See race attendence bonus programs, 95 Auto Club Speedway, 192, 194, 198–199 brake fan, 71 Autodromo Hermanos Rodriguez, 36 brake pedal, 70, 71, 107 autograph card, 245COPYRIGHTEDbrakes, MATERIAL -

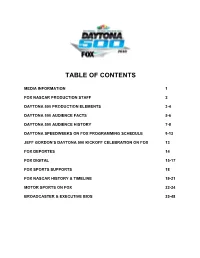

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION 1 FOX NASCAR PRODUCTION STAFF 2 DAYTONA 500 PRODUCTION ELEMENTS 3-4 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE FACTS 5-6 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE HISTORY 7-8 DAYTONA SPEEDWEEKS ON FOX PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE 9-12 JEFF GORDON’S DAYTONA 500 KICKOFF CELEBRATION ON FOX 13 FOX DEPORTES 14 FOX DIGITAL 15-17 FOX SPORTS SUPPORTS 18 FOX NASCAR HISTORY & TIMELINE 19-21 MOTOR SPORTS ON FOX 22-24 BROADCASTER & EXECUTIVE BIOS 25-48 MEDIA INFORMATION The FOX NASCAR Daytona 500 press kit has been prepared by the FOX Sports Communications Department to assist you with your coverage of this year’s “Great American Race” on Sunday, Feb. 21 (1:00 PM ET) on FOX and will be updated continuously on our press site: www.foxsports.com/presspass. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to provide further information and facilitate interview requests. Updated FOX NASCAR photography, featuring new FOX NASCAR analyst and four-time NASCAR champion Jeff Gordon, along with other FOX on-air personalities, can be downloaded via the aforementioned FOX Sports press pass website. If you need assistance with photography, contact Ileana Peña at 212/556-2588 or [email protected]. The 59th running of the Daytona 500 and all ancillary programming leading up to the race is available digitally via the FOX Sports GO app and online at www.FOXSportsGO.com. FOX SPORTS ON-SITE COMMUNICATIONS STAFF Chris Hannan EVP, Communications & Cell: 310/871-6324; Integration [email protected] Lou D’Ermilio SVP, Media Relations Cell: 917/601-6898; [email protected] Erik Arneson VP, Media Relations Cell: 704/458-7926; [email protected] Megan Englehart Publicist, Media Relations Cell: 336/425-4762 [email protected] Eddie Motl Manager, Media Relations Cell: 845/313-5802 [email protected] Claudia Martinez Director, FOX Deportes Media Cell: 818/421-2994; Relations claudia.martinez@foxcom 2016 DAYTONA 500 MEDIA CONFERENCE CALL & REPLAY FOX Sports is conducting a media event and simultaneous conference call from the Daytona International Speedway Infield Media Center on Thursday, Feb. -

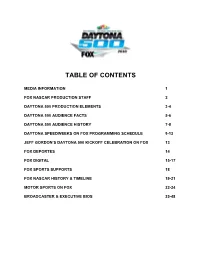

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION 1 FOX NASCAR PRODUCTION STAFF 2 DAYTONA 500 PRODUCTION ELEMENTS 3-4 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE FACTS 5-6 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE HISTORY 7-8 DAYTONA SPEEDWEEKS ON FOX PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE 9-12 JEFF GORDON’S DAYTONA 500 KICKOFF CELEBRATION ON FOX 13 FOX DEPORTES 14 FOX DIGITAL 15-17 FOX SPORTS SUPPORTS 18 FOX NASCAR HISTORY & TIMELINE 19-21 MOTOR SPORTS ON FOX 22-24 BROADCASTER & EXECUTIVE BIOS 25-48 MEDIA INFORMATION The FOX NASCAR Daytona 500 press kit has been prepared by the FOX Sports Communications Department to assist you with your coverage of this year’s “Great American Race” on Sunday, Feb. 21 (1:00 PM ET) on FOX and will be updated continuously on our press site: www.foxsports.com/presspass. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to provide further information and facilitate interview requests. Updated FOX NASCAR photography, featuring new FOX NASCAR analyst and four-time NASCAR champion Jeff Gordon, along with other FOX on-air personalities, can be downloaded via the aforementioned FOX Sports press pass website. If you need assistance with photography, contact Ileana Peña at 212/556-2588 or [email protected]. The 59th running of the Daytona 500 and all ancillary programming leading up to the race is available digitally via the FOX Sports GO app and online at www.FOXSportsGO.com. FOX SPORTS ON-SITE COMMUNICATIONS STAFF Chris Hannan EVP, Communications & Cell: 310/871-6324; Integration [email protected] Lou D’Ermilio SVP, Media Relations Cell: 917/601-6898; [email protected] Erik Arneson VP, Media Relations Cell: 704/458-7926; [email protected] Megan Englehart Publicist, Media Relations Cell: 336/425-4762 [email protected] Eddie Motl Manager, Media Relations Cell: 845/313-5802 [email protected] Claudia Martinez Director, FOX Deportes Media Cell: 818/421-2994; Relations claudia.martinez@foxcom 2016 DAYTONA 500 MEDIA CONFERENCE CALL & REPLAY FOX Sports is conducting a media event and simultaneous conference call from the Daytona International Speedway Infield Media Center on Thursday, Feb. -

Are Ers Rave Rain O I"Ea Si Ence Christopher Clancy Staff

.<) <tii)f ~l THE UNIVERSITY OF IDAHO Q,i Frida, 4 ril 26, 1996 ASUI —Moscow Idaho Volume 97 No. $9 are ers rave rain o i"ea si ence Christopher Clancy Staff sudden spring shower may have damp- ened heads, but certainly did not dampen pirits, as a small group of marchers showed their solidarity in the fight against sexual assault in the Break the Silence rally. The event was the kick-off for the University of Idaho's Sexual Assault Awareness Week sponsored by the Women's Center and the ASUI Safety Task Force. The march, which began at Guy Wicks Field, took marchers on a winding tour of campus, lead by Safety Task Force Chair Angela Rauch and Vice-Chair Rhonda Anderson. "Last year over 119 cases of abuse have been reported to the Women's Center. We need to increase awareness and help victims of these types of violent crimes to gain the courage to . speak out and get help," Anderson said. z'4w" 4. During the march a whistle was blown every 15 seconds, signifying the statistic of one woman battered in the United States every 15 ~A'!. seconds. Similarly, each minute a bell was rung, signifying the rape of one woman. The march ended on the steps of the Administration Building where poetry, written by victims, was read and family members and survivors spoke about loss and hope. The mes- t. sage alw'ays: "Fight back, it's not your fault, get help, you'e not alone" was heard as encourage- ment from the victims and their families. -

Playstation Games

The Video Game Guy, Booths Corner Farmers Market - Garnet Valley, PA 19060 (302) 897-8115 www.thevideogameguy.com System Game Genre Playstation Games Playstation 007 Racing Racing Playstation 101 Dalmatians II Patch's London Adventure Action & Adventure Playstation 102 Dalmatians Puppies to the Rescue Action & Adventure Playstation 1Xtreme Extreme Sports Playstation 2Xtreme Extreme Sports Playstation 3D Baseball Baseball Playstation 3Xtreme Extreme Sports Playstation 40 Winks Action & Adventure Playstation Ace Combat 2 Action & Adventure Playstation Ace Combat 3 Electrosphere Other Playstation Aces of the Air Other Playstation Action Bass Sports Playstation Action Man Operation EXtreme Action & Adventure Playstation Activision Classics Arcade Playstation Adidas Power Soccer Soccer Playstation Adidas Power Soccer 98 Soccer Playstation Advanced Dungeons and Dragons Iron and Blood RPG Playstation Adventures of Lomax Action & Adventure Playstation Agile Warrior F-111X Action & Adventure Playstation Air Combat Action & Adventure Playstation Air Hockey Sports Playstation Akuji the Heartless Action & Adventure Playstation Aladdin in Nasiras Revenge Action & Adventure Playstation Alexi Lalas International Soccer Soccer Playstation Alien Resurrection Action & Adventure Playstation Alien Trilogy Action & Adventure Playstation Allied General Action & Adventure Playstation All-Star Racing Racing Playstation All-Star Racing 2 Racing Playstation All-Star Slammin D-Ball Sports Playstation Alone In The Dark One Eyed Jack's Revenge Action & Adventure -

The BG News April 24, 1997

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 4-24-1997 The BG News April 24, 1997 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News April 24, 1997" (1997). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6171. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6171 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. TODAY Directory SPORTS WORLD 5 Switchboard 372-2601 Classified Ads 372-6977 If anybody can Men's Golf Baseball Hostage crisis Display Ads 372-2605 make BG a ends in Peru Editorial 372-6966 Highest finish BG 1 ...1 -Sports 372-2602 basketball with shootout; all Entertainment 372-2603 school, Dan of season Ball St. ...2.11 14 rebels killed, Slnry idea? Give us a call Falcons take second Falcons drop pair to partly cloudy Dakich can place at Ohio Colle- but only one weekdays from I pm. lo 5 pm., or Cardinals; Ball State captive dies e-mail: "[email protected]" Column, page 6 giate Classic assumes conference lead High: 55 Low: 40 THURSDAY April 24,1997 Volume 83, Issue 141 The BG News Bowling Green, Ohio "Serving the Bowling Green community for over 75years" # Speakers chosen for spring graduation □ As spring graduation ap- Almost 2,000 students will be receiv- and Health and Human Services will held this year.