The Geographical Focus and Conceivable Activity Options for the Proposed LIFT Dry Zone Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June Lawyer Kyi Myint and Poet Saw Wai Held a Press JANUARY Chronologyconference Regarding the Arrest Warrant2020 Against

June Lawyer Kyi Myint and Poet Saw Wai held a press JANUARY CHRONOLOGYconference regarding the arrest warrant2020 against them. Summary of the Current Situation: 647 individuals are oppressed in Burma due to political activity: 73 political prisoners are serving sentences, 141 are awaiting trial inside prison, 433 are awaiting trial outside Accessed January © Myanmar Times prison. WEBSITE | TWITTER | FACEBOOK January 2020 1 ACRONYMS ABFSU All Burma Federation of Student Unions CAT Conservation Alliance Tanawthari CNPC China National Petroleum Corporation EAO Ethnic Armed Organization GEF Global Environment Facility ICRC International Committee of the Red Cross IDP Internally Displaced Person KHRG Karen Human Rights Group KIA Kachin Independence Army KNU Karen National Union MFU Myanmar Farmers’ Union MNHRC Myanmar National Human Rights Commission MOGE Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise NLD National League for Democracy NNC Naga National Council PAPPL Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law RCSS Restoration Council of Shan State RCSS/SSA Restoration Council of Shan State/Shan State Army – South SHRF Shan Human Rights Foundation TNLA Ta’ang National Liberation Army YUSU Yangon University Students’ Union January 2020 2 POLITICAL PRISONERS Note - Changes have been made to the layout and content of the Chronology. AAPP will no longer cover landmine cases and conflict between ethnic armed groups (EAGs) due to resources; detentions and torture by EAGs will still be covered. Additionally, AAPP will not cover individual protests by land rights, but will provide updates on the arrests of land rights activists. Political Prisoners ARRESTS Two RCSS members arrested in Namhsan On January 6, the military arrested two members of the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS) who attended a public meeting at Nar Bwe Village in Namhsan Township in southern Shan State. -

46399E642.Pdf

PGDS in DOS Myanmar Atlas Map Population and Geographic Data Section As of January 2006 Division of Operational Support Email : [email protected] ((( Yüeh-hsi ((( ((( Zayü ((( ((( BANGLADESHBANGLADESH ((( Xichang ((( Zhongdian ((( Ho-pien-tsun Cox'sCox's BazarBazar ((( ((( ((( ((( Dibrugrh ((( ((( ((( (((Meiyu ((( Dechang THIMPHUTHIMPHU ((( ((( ((( Myanmar_Atlas_A3PC.WOR ((( Ningnan ((( ((( Qiaojia ((( Dayan ((( Yongsheng KutupalongKutupalong ((( Huili ((( ((( Golaghat ((( Jianchuan ((( Huize ((( ((( ((( Cooch Behar ((( North Gauhati Nowgong (((( ((( Goalpara (((( Gauhati MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( Dinhata ((( ((( Gauripur ((( Dongch ((( ((( ((( Dengchuan ((( Longjie ((( Lalmanir Hat ((( Yanfeng ((( Rangpur ((( ((( ((( ((( Yuanmou ((( Yangbi((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( Shillong ((((( Xundia ((( ((( Hai-tzu-hsin ((( Yongping ((( Xiangyun ((( ((( ((( Myitkyina ((( ((( ((( Heijing ((( Gaibanda NayaparaNayapara ((((( ((( (Sha-chiao(( ((( ((( ((( ((( Yipinglang ((( Baoshan TeknafTeknaf ButhidaungButhidaung (((TeknafTeknaf ((( ((( Nanjian ((( !! ((( Tengchong KanyinKanyin((( ChaungChaung !! Kunming ((( ((( ((( Anning ((( ((( ((( Changning MaungdawMaungdaw ((( MaungdawMaungdaw ((( ((( Imphal Mymensingh ((( ((( ((( ((( Jiuyingjiang ((( ((( Longling 000 202020 404040 BANGLADESHBANGLADESH((( 000 202020 404040 BANGLADESHBANGLADESH((( ((( ((( ((( ((( Yunxian ((( ((( ((( ((( -

Rakhine State

Myanmar Information Management Unit Township Map - Rakhine State 92° E 93° E 94° E Tilin 95° E Township Myaing Yesagyo Pauk Township Township Bhutan Bangladesh Kyaukhtu !( Matupi Mindat Mindat Township India China Township Pakokku Paletwa Bangladesh Pakokku Taungtha Samee Ü Township Township !( Pauk Township Vietnam Taungpyoletwea Kanpetlet Nyaung-U !( Paletwa Saw Township Saw Township Ngathayouk !( Bagan Laos Maungdaw !( Buthidaung Seikphyu Township CHIN Township Township Nyaung-U Township Kanpetlet 21° N 21° Township MANDALAYThailand N 21° Kyauktaw Seikphyu Chauk Township Buthidaung Kyauktaw KyaukpadaungCambodia Maungdaw Chauk Township Kyaukpadaung Salin Township Mrauk-U Township Township Mrauk-U Salin Rathedaung Ponnagyun Township Township Minbya Rathedaung Sidoktaya Township Township Yenangyaung Yenangyaung Sidoktaya Township Minbya Pwintbyu Pwintbyu Ponnagyun Township Pauktaw MAGWAY Township Saku Sittwe !( Pauktaw Township Minbu Sittwe Magway Magway .! .! Township Ngape Myebon Myebon Township Minbu Township 20° N 20° Minhla N 20° Ngape Township Ann Township Ann Minhla RAKHINE Township Sinbaungwe Township Kyaukpyu Mindon Township Thayet Township Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Mindon Township !( Bay of Bengal Ramree Kamma Township Kamma Ramree Toungup Township Township 19° N 19° N 19° Munaung Toungup Munaung Township BAGO Padaung Township Thandwe Thandwe Township Kyangin Township Myanaung Township Kyeintali !( 18° N 18° N 18° Legend ^(!_ Capital Ingapu .! State Capital Township Main Town Map ID : MIMU1264v02 Gwa !( Other Town Completion Date : 2 November 2016.A1 Township Projection/Datum : Geographic/WGS84 Major Road Data Sources :MIMU Base Map : MIMU Lemyethna Secondary Road Gwa Township Boundaries : MIMU/WFP Railroad Place Name : Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) translated by MIMU AYEYARWADY Coast Map produced by the MIMU - [email protected] Township Boundary www.themimu.info Copyright © Myanmar Information Management Unit Yegyi Ngathaingchaung !( State/Region Boundary 2016. -

Members of Parliament-Elect, Myanmar/Burma

To: Hon. Mr. Ban Ki-moon Secretary-General United Nations From: Members of Parliament-Elect, Myanmar/Burma CC: Mr. B. Lynn Pascoe, Under-Secretary-General, United Nations Mr. Ibrahim Gambari, Under-Secretary-General and Special Adviser to the Secretary- General on Myanmar/Burma Permanent Representatives to the United Nations of the five Permanent Members (China, Russia, France, United Kingdom and the United states) of the UN Security Council U Aung Shwe, Chairman, National League for Democracy Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, General Secretary, National League for Democracy U Aye Thar Aung, Secretary, Committee Representing the Peoples' Parliament (CRPP) Veteran Politicians The 88 Generation Students Date: 1 August 2007 Re: National Reconciliation and Democratization in Myanmar/Burma Dear Excellency, We note that you have issued a statement on 18 July 2007, in which you urged the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) (the ruling military government of Myanmar/Burma) to "seize this opportunity to ensure that this and subsequent steps in Myanmar's political roadmap are as inclusive, participatory and transparent as possible, with a view to allowing all the relevant parties to Myanmar's national reconciliation process to fully contribute to defining their country's future."1 We thank you for your strong and personal involvement in Myanmar/Burma and we expect that your good offices mandate to facilitating national reconciliation in Myanmar/Burma would be successful. We, Members of Parliament elected by the people of Myanmar/Burma in the 1990 general elections, also would like to assure you that we will fully cooperate with your good offices and the United Nations in our effort to solve problems in Myanmar/Burma peacefully through a meaningful, inclusive and transparent dialogue. -

MAGWAY REGION, PAKOKKU DISTRICT Seikphyu Township Report

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census MAGWAY REGION, PAKOKKU DISTRICT Seikphyu Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population October 2017 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Magway Region, Pakokku District Seikphyu Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm October 2017 Figure 1: Map of Magway Region, showing the townships Seikphyu Township Figures at a Glance 1 Total Population 102,769 2 Population males 46,909 (45.6%) Population females 55,860 (54.4%) Percentage of urban population 8.8% Area (Km2) 1,523.4 3 Population density (per Km2) 67.5 persons Median age 27.1 years Number of wards 4 Number of village tracts 42 Number of private households 23,427 Percentage of female headed households 26.8% Mean household size 4.2 persons 4 Percentage of population by age group Children (0 – 14 years) 30.3% Economically productive (15 – 64 years) 63.4% Elderly population (65+ years) 6.3% Dependency ratios Total dependency ratio 57.9 Child dependency ratio 47.9 Old dependency ratio 10.0 Ageing index 20.9 Sex ratio (males per 100 females) 84 Literacy rate (persons aged 15 and over) 91.4% Male 95.2% Female 88.4% People with disability Number Per cent Any form of disability 4,832 4.7 Walking 1,862 1.8 Seeing 2,395 2.3 Hearing 1,430 1.4 Remembering 1,605 1.6 Type of Identity Card (persons aged 10 and over) Number Per cent Citizenship Scrutiny 63,461 -

Second National Report on Unccd Implementation of the Union of Myanmar ( April 2002 )

SECOND NATIONAL REPORT ON UNCCD IMPLEMENTATION OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR ( APRIL 2002 ) Contents Page 1. Executive Summary 1 2. Background 3 3. The Strategies and Priorities Established within the Framework of 7 Sustainable Economic Development Plans 4. Institutional Measures Taken to Implement the Convention 9 5. Measures Taken or Planned to Combat Desertification 14 6. Consultative Process in Support of National Action Programme 52 with Interested Entities 7. Financial Allocation from the National Budgets 56 8. Monitoring and Evaluation 58 1. Executive Summary 1.1 The main purpose of this report is to update on the situation in Myanmar with regard to measures taken for the implementation of the UNCCD at the national level since its submission of the first national report in August 2000. 1.2 Myanmar acceded to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) in January 1997. Even before Myanmar’s accession to UNCCD, measures relating to combating desertification have been taken at the local and national levels. In 1994, the Ministry of Forestry (MOF) launched a 3-year "Greening Project for the Nine Critical Districts" of Sagaing, Magway and Mandalay Divisions in the Dry Zone. This was later extended to 13 districts with the creation of new department, the Dry Zone Greening Department (DZGD) in 1997. 1.3 The Government has stepped up its efforts on preventing land degradation and combating desertification in recent years. The most significant effort is the rural area development programme envisaged in the current Third Short-Term Five-Year Plan (2001-2002 to 2005-2006). The rural development programme has laid down 5 main activities. -

Title Around the Sagaing Township in Kon-Baung Period All Authors Moe

Title Around the Sagaing Township in Kon-baung Period All Authors Moe Moe Oo Publication Type Local Publication Publisher (Journal name, Myanmar Historical Research Journal, No-21 issue no., page no etc.) Sagaing Division was inhabited by Stone Age people. Sagaing town was a place where the successive kings of Pagan, Innwa and Kon-baungs period constructed religious buildings. Hence it can be regarded as an important place not only for military matters, but also for the administration of the kingdom. Moreover, a considerable number of foreigners were Siamese, Yuns and Manipuris also settled in Sagaing township. Its population was higher than that of Innwa and Abstract lower than that of Amarapura. Therefore, it can be regarded as a medium size town. Agriculture has been the backbone of Sagaing township’s economy since the Pagan period. The Sagaing must have been prosperous but the deeds of land and other mortgages highlight the economic difficulties of the area. It is learnt from the documents concerning legal cases that arose in this area. As Sagaing was famous for its silverware industry, silk-weaving and pottery, it can be concluded that the cultural status was high. Keywords Historical site, military forces, economic aspect, cultural heigh Citation Issue Date 2011 Myanmar Historical Research Journal, No-21, June 2011 149 Around the Sagaing Township in Kon-baung Period By Dr. Moe Moe Oo1 Background History Sagaing Division comprises the tracts between Ayeyarwady and Chindwin rivers, and the earliest fossil remains and remains of Myanmar’s prehistoric culture have been discovered there. A fossilized mandible of a primate was discovered in April 1978 from the Pondaung Formation, a mile to the northwest of Mogaung village, Pale township, Sagaing township. -

Maj-Gen Khin Zaw of Ministry of Defence Meets Tatmadaw Members in Aunglan Township

Panditanañ ca sevana, to associate with the wise; this is the way to auspiciousness Established 1914 Volume XVI, Number 123 3rd Waning of Wagaung 1370 ME Tuesday, 19 August, 2008 Four political objectives Four economic objectives Four social objectives * Stability of the State, community peace * Development of agriculture as the base and all-round * Uplift of the morale and morality of development of other sectors of the economy as well and tranquillity, prevalence of law and the entire nation * Proper evolution of the market-oriented economic order * Uplift of national prestige and integ- system * National reconsolidation rity and preservation and safeguard- * Development of the economy inviting participation in * Emergence of a new enduring State ing of cultural heritage and national terms of technical know-how and investments from Constitution character sources inside the country and abroad * Building of a new modern developed * Uplift of dynamism of patriotic spirit * The initiative to shape the national economy must be kept * Uplift of health, fitness and education nation in accord with the new State in the hands of the State and the national peoples Constitution standards of the entire nation Maj-Gen Khin Zaw of Ministry of Defence meets Tatmadaw members in Aunglan Township Maj-Gen Khin Zaw inspects collective cultivation of paddy on the farm of farmer Daw Khin San at Kwanlon Village tract in Aunglan Township.—MNA NAY PYI TAW, 18 Aug also met departmental of- in Aunglan, 44,618 acres paddy on the farm of road section. Myanma Kyangin-Thayet – Maj-Gen Khin Zaw of ficials, members of social in Thayet District and farmer Daw Khin San in Railways is implementing Railroad project includes the Ministry of Defence organizations and local 115,818 acres in Magway Kwanlon Village tract the 320-mile Kyangin- 40-mile Kyangin- and Chairman of Magway people at Aungmye Division. -

Laboratory Aspects in Vpds Surveillance and Outbreak Investigation

Laboratory Aspect of VPD Surveillance and Outbreak Investigation Dr Ommar Swe Tin Consultant Microbiologist In-charge National Measles & Rubella Lab, Arbovirus section, National Influenza Centre NHL Fever with Rash Surveillance Measles and Rubella Achieving elimination of measles and control of rubella/CRS by 2020 – Regional Strategic Plan Key Strategies: 1. Immunization 2. Surveillance 3. Laboratory network 4. Support & Linkages Network of Regional surveillance officers (RSO) and Laboratories NSC Office 16 RSOs Office Subnational Measles & Rubella Lab, Subnational JE lab National Measles/Rubella Lab (NHL, Yangon) • Surveillance began in 2003 • From 2005 onwards, case-based diagnosis was done • Measles virus isolation was done since 2006 • PCR since 2016 Sub-National Measles/Rubella Lab (PHL, Mandalay) • Training 29.8.16 to 2.9.16 • Testing since Nov 2016 • Accredited in Oct 2017 Measles Serology Data Measles Measles IgM Measles IgM Measles IgM Test Done Positive Negative Equivocal 2011 1766 1245 452 69 2012 1420 1182 193 45 2013 328 110 212 6 2014 282 24 254 4 2015 244 6 235 3 2016 531 181 334 16 2017 1589 1023 503 62 Rubella Serology Data Rubella Test Rubella IgM Rubella IgM Rubella IgM Done Positive Negative Equivocal 2011 425 96 308 21 2012 195 20 166 9 2013 211 23 185 3 2014 257 29 224 4 2015 243 34 196 13 2016 535 12 511 12 2017 965 8 948 9 Measles Genotypes circulating in Myanmar 1. Isolation in VERO h SLAM cell line 2. Positive culture shows syncytia formation 3. Isolated MeV or sample by PCR 4. Positive PCR product is sent to RRL for sequencing 5. -

Country Report Myanmar

Country Report Myanmar Natural Disaster Risk Assessment and Area Business Continuity Plan Formulation for Industrial Agglomerated Areas in the ASEAN Region March 2015 AHA CENTRE Japan International Cooperation Agency OYO International Corporation Mitsubishi Research Institute, Inc. CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. Overview of the Country Basic Information of Myanmar 1), 2), 3) National Flag Country Name Long form: Republic of the Union of Myanmar Short form: Myanmar Capital Naypidaw Area (km2) Total : 676,590 Land: 653,290 Inland Water: 23,300 Population 53,259,018 Population density 82 (people/km2 of land area) Population growth 0.9 (annual %) Urban population 33 (% of total) Languages Myanmar Ethnic Groups Burmese (about 70%),many other ethnic groups Religions Buddhism (90%), Christianity, Islam, others GDP (current US$) (billion) 55(Estimate) GNI per capita, PPP - (current international $) GDP growth (annual %) 6.4(Estimate) Agriculture, value added 48 (% of GDP) Industry, value added 16 (% of GDP) Services, etc., value added 35 (% of GDP) Brief Description Myanmar covers the western part of Indochina Peninsula, and the land area is about 1.8 times the size of Japan. Myanmar has a long territory stretching north to south, with the Irrawaddy River running through the heart of the country. While Burmese is the largest ethnic group in the country, the country has many ethnic minorities. Myanmar joined ASEAN on July 23, 1997, together with Laos. Due to the isolationist policy adopted by the military government led by Ne Win which continued until 1988, the economic development of Myanmar fell far behind other ASEAN countries. Today, Myanmar is a republic, and President Thein Sein is the head of state. -

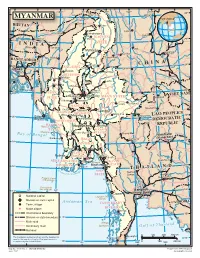

Map of Myanmar

94 96 98 J 100 102 ° ° Indian ° i ° ° 28 n ° Line s Xichang Chinese h a MYANMAR Line J MYANMAR i a n Tinsukia g BHUTAN Putao Lijiang aputra Jorhat Shingbwiyang M hm e ra k Dukou B KACHIN o Guwahati Makaw n 26 26 g ° ° INDIA STATE n Shillong Lumding i w d Dali in Myitkyina h Kunming C Baoshan BANGLADE Imphal Hopin Tengchong SH INA Bhamo C H 24° 24° SAGAING Dhaka Katha Lincang Mawlaik L Namhkam a n DIVISION c Y a uan Gejiu Kalemya n (R Falam g ed I ) Barisal r ( r Lashio M a S e w k a o a Hakha l n Shwebo w d g d e ) Chittagong y e n 22° 22° CHIN Monywa Maymyo Jinghong Sagaing Mandalay VIET NAM STATE SHAN STATE Pongsali Pakokku Myingyan Ta-kaw- Kengtung MANDALAY Muang Xai Chauk Meiktila MAGWAY Taunggyi DIVISION Möng-Pan PEOPLE'S Minbu Magway Houayxay LAO 20° 20° Sittwe (Akyab) Taungdwingyi DEMOCRATIC DIVISION y d EPUBLIC RAKHINE d R Ramree I. a Naypyitaw Loikaw w a KAYAH STATE r r Cheduba I. I Prome (Pye) STATE e Bay Chiang Mai M kong of Bengal Vientiane Sandoway (Viangchan) BAGO Lampang 18 18° ° DIVISION M a e Henzada N Bago a m YANGON P i f n n o aThaton Pathein g DIVISION f b l a u t Pa-an r G a A M Khon Kaen YEYARWARDY YangonBilugyin I. KAYIN ATE 16 16 DIVISION Mawlamyine ST ° ° Pyapon Amherst AND M THAIL o ut dy MON hs o wad Nakhon f the Irra STATE Sawan Nakhon Preparis Island Ratchasima (MYANMAR) Ye Coco Islands 92 (MYANMAR) 94 Bangkok 14° 14° ° ° Dawei (Krung Thep) National capital Launglon Bok Islands Division or state capital Andaman Sea CAMBODIA Town, village TANINTHARYI Major airport DIVISION Mergui International boundary 12° Division or state boundary 12° Main road Mergui n d Secondary road Archipelago G u l f o f T h a i l a Railroad 0 100 200 300 km Chumphon The boundaries and names shown and the designations Kawthuang 10 used on this map do not imply official endorsement or ° acceptance by the United Nations. -

MYANMAR A? Flood Kachin, Shan (North) State and Sagaing, Mandalay, Magway Region Imagery Analysis: 25 July 2020 | Published 5 August 2020 | Version 1.0 FL20200730MMR

MYANMAR A? Flood Kachin, Shan (North) State and Sagaing, Mandalay, Magway Region Imagery analysis: 25 July 2020 | Published 5 August 2020 | Version 1.0 FL20200730MMR 94?40'0"E 95?20'0"E 96?0'0"E 96?40'0"E 97?20'0"E M O H N Y I N M Y I T K Y I N A H K A M T I Map location T A M U K A T H A K A C H I N B H A M O M Y A N M A R N " 0 ' 0 ? N 4 " 2 0 ' 0 ? 4 2 M AW L A I K K A W L I N M U S E M O N G M I T N " 0 ' 0 2 N ? " 3 0 ' 2 0 2 ? K A N B A L U Satellite detected water extent as 3 2 S A G A I N G of 25 July 2020 in central part of P A L A U N G S E L F - A D M I N I S T E R E D Z O N E Myanmar This map illustrates satellite-detected surface K A L E L A S H I O S H A N ( N O R T H ) waters over Kachin, Shan (North) State and MOGOK Sagaing, Mandalay, Magway Region of Myanmar as observed from a Terra(MODIS) L A S H I O N " 0 image acquired on 25 July 2020 due to the ' S H W E B O 0 4 N ? " 2 0 ' 2 current monsoon rains.