1999 Country Reports on Economic Policy and Trade Practices Released by the Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Currency Codes COP Colombian Peso KWD Kuwaiti Dinar RON Romanian Leu

Global Wire is an available payment method for the currencies listed below. This list is subject to change at any time. Currency Codes COP Colombian Peso KWD Kuwaiti Dinar RON Romanian Leu ALL Albanian Lek KMF Comoros Franc KGS Kyrgyzstan Som RUB Russian Ruble DZD Algerian Dinar CDF Congolese Franc LAK Laos Kip RWF Rwandan Franc AMD Armenian Dram CRC Costa Rican Colon LSL Lesotho Malati WST Samoan Tala AOA Angola Kwanza HRK Croatian Kuna LBP Lebanese Pound STD Sao Tomean Dobra AUD Australian Dollar CZK Czech Koruna LT L Lithuanian Litas SAR Saudi Riyal AWG Arubian Florin DKK Danish Krone MKD Macedonia Denar RSD Serbian Dinar AZN Azerbaijan Manat DJF Djibouti Franc MOP Macau Pataca SCR Seychelles Rupee BSD Bahamian Dollar DOP Dominican Peso MGA Madagascar Ariary SLL Sierra Leonean Leone BHD Bahraini Dinar XCD Eastern Caribbean Dollar MWK Malawi Kwacha SGD Singapore Dollar BDT Bangladesh Taka EGP Egyptian Pound MVR Maldives Rufi yaa SBD Solomon Islands Dollar BBD Barbados Dollar EUR EMU Euro MRO Mauritanian Olguiya ZAR South African Rand BYR Belarus Ruble ERN Eritrea Nakfa MUR Mauritius Rupee SRD Suriname Dollar BZD Belize Dollar ETB Ethiopia Birr MXN Mexican Peso SEK Swedish Krona BMD Bermudian Dollar FJD Fiji Dollar MDL Maldavian Lieu SZL Swaziland Lilangeni BTN Bhutan Ngultram GMD Gambian Dalasi MNT Mongolian Tugrik CHF Swiss Franc BOB Bolivian Boliviano GEL Georgian Lari MAD Moroccan Dirham LKR Sri Lankan Rupee BAM Bosnia & Herzagovina GHS Ghanian Cedi MZN Mozambique Metical TWD Taiwan New Dollar BWP Botswana Pula GTQ Guatemalan Quetzal -

View Currency List

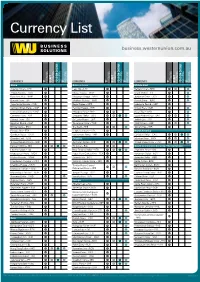

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Zimra Rates of Exchange for Customs Purposes for the Period 08 to 14 July

ZIMRA RATES OF EXCHANGE FOR CUSTOMS PURPOSES FOR THE PERIOD 08 TO 14 JULY 2021 USD BASE CURRENCY - USD DOLLAR CURRENCY CODE CROSS RATE ZIMRA RATE CURRENCY CODE CROSS RATE ZIMRA RATE ANGOLA KWANZA AOA 650.4178 0.0015 MALAYSIAN RINGGIT MYR 4.1598 0.2404 ARGENTINE PESO ARS 95.9150 0.0104 MAURITIAN RUPEE MUR 42.8000 0.0234 AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR AUD 1.3329 0.7503 MOROCCAN DIRHAM MAD 8.9490 0.1117 AUSTRIA EUR 0.8454 1.1829 MOZAMBICAN METICAL MZN 63.9250 0.0156 BAHRAINI DINAR BHD 0.3760 2.6596 NAMIBIAN DOLLAR NAD 14.3346 0.0698 BELGIUM EUR 0.8454 1.1829 NETHERLANDS EUR 0.8454 1.1829 BOTSWANA PULA BWP 10.9709 0.0912 NEW ZEALAND DOLLAR NZD 1.4232 0.7027 BRAZILIAN REAL BRL 5.1970 0.1924 NIGERIAN NAIRA NGN 410.9200 0.0024 BRITISH POUND GBP 0.7241 1.3810 NORTH KOREAN WON KPW 900.0228 0.0011 BURUNDIAN FRANC BIF 1983.5620 0.0005 NORWEGIAN KRONER NOK 8.7064 0.1149 CANADIAN DOLLAR CAD 1.2459 0.8026 OMANI RIAL OMR 0.3845 2.6008 CHINESE RENMINBI YUAN CNY 6.4690 0.1546 PAKISTANI RUPEE PKR 158.3558 0.0063 CUBAN PESO CUP 24.0957 0.0415 POLISH ZLOTY PLN 3.8154 0.2621 CYPRIOT POUND EUR 0.8454 1.1829 PORTUGAL EUR 0.8454 1.1829 CZECH KORUNA CZK 21.6920 0.0461 QATARI RIYAL QAR 3.6400 0.2747 DANISH KRONER DKK 6.2866 0.1591 RUSSIAN RUBLE RUB 74.2305 0.0135 EGYPTIAN POUND EGP 15.6900 0.0637 RWANDAN FRANC RWF 1001.5019 0.0010 ETHOPIAN BIRR ETB 43.9164 0.0228 SAUDI ARABIAN RIYAL SAR 3.7500 0.2667 EURO EUR 0.8454 1.1829 SINGAPORE DOLLAR SGD 1.3478 0.7419 FINLAND EUR 0.8454 1.1829 SPAIN EUR 0.8454 1.1829 FRANCE EUR 0.8454 1.1829 SOUTH AFRICAN RAND ZAR 14.3346 0.0698 GERMANY -

Qatar Destination Guide

Qatar Destination Guide Overview of Qatar The stark desert peninsula of Qatar extends into the Persian Gulf, bordered by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Its area may be small, but the independent emirate is exceedingly wealthy, with one of the highest per capita incomes in the world thanks to its oil and gas resources. Whether visiting Qatar for business or pleasure, most travellers make the stylish capital of Doha their base. Formerly a quaint and busy pearl-diving and fishing village, Doha is today one of the most prominent cities in the Middle East owing mainly to its importance as a major trading centre. It has a large British and American expatriate population (the Al Udeid air base was headquarters for the US invasion of Iraq in 2003), which has moulded the city into an interesting blend of eastern and western culture and architecture. Tourists tend to spend their time on the Doha Corniche, a palm-fringed public promenade that extends for four miles (7km) along the seafront and is lined with five and six-star resort hotels, restaurants, shops, beaches and recreational areas. Although there is some adventure to be found in the glittering sands beyond Doha, the biggest drawcard for visitors to Qatar is shopping, whether it is in the exotic traditional markets (souqs) or the plethora of massive ultramodern malls that fill the city centre. In addition to this impressive retail offering, Doha is fast becoming a sought after destination for foodies because of its sophisticated fine-dining scene. Those who want to explore outside the city can undertake excursions to interesting little towns, fishing villages, beautiful beaches, camel racing events, luxury resorts, and the Al Maha Sanctuary at Shahaniya, where the near-extinct Arabian Oryx is being protected. -

Project Paper Fisheries Development Projecl 272-0101.1

Project Paper Fisheries Development ProjecL 272-0101.1 1. TRANSACTION CODE AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL. DEVELOPMENT A ADD PP A C C.HANGE Sub- PROJECT PAPER FACESHEET 0DELETE 2. CODOCUMENT E CO 3 3. COUNTRY'ENTITY 4. DOCUMENT REVISION NUMBER Oman D S. PROJECT NUMBER (7 dijits) 6. BUREAU/OFFICE 7. PROJECT TITLE (Maximum 40 characters) Z-272-OlOl J A.S,M3oL . CODE NEiTECH .o3] [:Fisheries Development Project 6.ESTIMATED FY OF PROJECT COMPLETION 9. ESTIMATED DATE OF OBLIGATION III A. INITIAL FY Lau.. 3. QUARTER FY C. FINAL FY 1 (Enter 1, 2, 3. or 4) 10. ESTIMATED COSTS ($000 OR EQUIVALENT S - 6. 600 A. FUNDING SOURCE From FY80 Grahr FY 82 LIFE OF PROJECT -- B. FX C. L C 0. TOTAL E, FX F. L/C G. TOTAL AID APPROPRIATED TOTAL IGRANTI ,, nn i .nn 6 nn I (LOAN I I I I C I I OTHER1 U.S. 2 HOST COUNTRY 1 .001,300 10,615 OTHER DONOR(S) TOTALS 6_600 1,300 2,615 6,600 10,615 17,184 11. PROPOSED BUDGET APPROPRIATED FUNDS (5000) 2 'A. APPRO. S. PRIMARY PRIMARY TECH. CODE E. IST FY N. 2ND FY - K. 3RD IFY PRIATION PURPOSE CODE C. GRANT LOAN D. Ir GRANT G . LOAN i. GRANT J. LOAN L. GRANT M. LOAN .).ESF 100 090 6,600 (2) (3) (41 TOTALS 1 IN-DEPI TH N. EVAL- 4TH FY_ Q. STH FY LIFE OF PROJECT 12. IN-DEPTH EVAL. _____ ____ __________UATION SCH EDU LEDI A. GRANT P. LOAN R. GRANT S. LOAN T. GRANT U. -

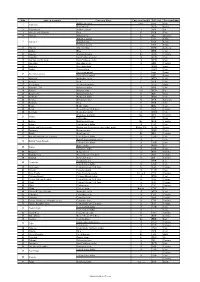

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates

The WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates The WM/Refinitiv Closing Exchange Rates are available on Eikon via monitor pages or RICs. To access the index page, type WMRSPOT01 and <Return> For access to the RICs, please use the following generic codes :- USDxxxFIXz=WM Use M for mid rate or omit for bid / ask rates Use USD, EUR, GBP or CHF xxx can be any of the following currencies :- Albania Lek ALL Austrian Schilling ATS Belarus Ruble BYN Belgian Franc BEF Bosnia Herzegovina Mark BAM Bulgarian Lev BGN Croatian Kuna HRK Cyprus Pound CYP Czech Koruna CZK Danish Krone DKK Estonian Kroon EEK Ecu XEU Euro EUR Finnish Markka FIM French Franc FRF Deutsche Mark DEM Greek Drachma GRD Hungarian Forint HUF Iceland Krona ISK Irish Punt IEP Italian Lira ITL Latvian Lat LVL Lithuanian Litas LTL Luxembourg Franc LUF Macedonia Denar MKD Maltese Lira MTL Moldova Leu MDL Dutch Guilder NLG Norwegian Krone NOK Polish Zloty PLN Portugese Escudo PTE Romanian Leu RON Russian Rouble RUB Slovakian Koruna SKK Slovenian Tolar SIT Spanish Peseta ESP Sterling GBP Swedish Krona SEK Swiss Franc CHF New Turkish Lira TRY Ukraine Hryvnia UAH Serbian Dinar RSD Special Drawing Rights XDR Algerian Dinar DZD Angola Kwanza AOA Bahrain Dinar BHD Botswana Pula BWP Burundi Franc BIF Central African Franc XAF Comoros Franc KMF Congo Democratic Rep. Franc CDF Cote D’Ivorie Franc XOF Egyptian Pound EGP Ethiopia Birr ETB Gambian Dalasi GMD Ghana Cedi GHS Guinea Franc GNF Israeli Shekel ILS Jordanian Dinar JOD Kenyan Schilling KES Kuwaiti Dinar KWD Lebanese Pound LBP Lesotho Loti LSL Malagasy -

Currency List

Americas & Caribbean | Tradeable Currency Breakdown Currency Currency Name New currency/ Buy Spot Sell Spot Deliverable Non-Deliverable Special requirements/ Symbol Capability Forward Forward Restrictions ANG Netherland Antillean Guilder ARS Argentine Peso BBD Barbados Dollar BMD Bermudian Dollar BOB Bolivian Boliviano BRL Brazilian Real BSD Bahamian Dollar CAD Canadian Dollar CLP Chilean Peso CRC Costa Rica Colon DOP Dominican Peso GTQ Guatemalan Quetzal GYD Guyana Dollar HNL Honduran Lempira J MD J amaican Dollar KYD Cayman Islands MXN Mexican Peso NIO Nicaraguan Cordoba PEN Peruvian New Sol PYG Paraguay Guarani SRD Surinamese Dollar TTD Trinidad/Tobago Dollar USD US Dollar UYU Uruguay Peso XCD East Caribbean Dollar 130 Old Street, EC1V 9BD, London | t. +44 (0) 203 475 5301 | [email protected] sugarcanecapital.com Europe | Tradeable Currency Breakdown Currency Currency Name New currency/ Buy Spot Sell Spot Deliverable Non-Deliverable Special requirements/ Symbol Capability Forward Forward Restrictions ALL Albanian Lek BGN Bulgarian Lev CHF Swiss Franc CZK Czech Koruna DKK Danish Krone EUR Euro GBP Sterling Pound HRK Croatian Kuna HUF Hungarian Forint MDL Moldovan Leu NOK Norwegian Krone PLN Polish Zloty RON Romanian Leu RSD Serbian Dinar SEK Swedish Krona TRY Turkish Lira UAH Ukrainian Hryvnia 130 Old Street, EC1V 9BD, London | t. +44 (0) 203 475 5301 | [email protected] sugarcanecapital.com Middle East | Tradeable Currency Breakdown Currency Currency Name New currency/ Buy Spot Sell Spot Deliverabl Non-Deliverabl Special Symbol Capability e Forward e Forward requirements/ Restrictions AED Utd. Arab Emir. Dirham BHD Bahraini Dinar ILS Israeli New Shekel J OD J ordanian Dinar KWD Kuwaiti Dinar OMR Omani Rial QAR Qatar Rial SAR Saudi Riyal 130 Old Street, EC1V 9BD, London | t. -

2021 49Er, 49Erfx & Nacra17 World Championships

2021 49er, 49erFX & Nacra17 World Championships 16 – 21 NOVEMBER 2021 Mussanah, OMAN Contents Oman At A Glance 4 Event Programme 6 Venue Location & Descriptions 8 Travel Information 10 Launching & Landing Sites 12 Shipping Information 14 Team Information 16 Press information 18 Contact Information 20 2 5th safest country Tourism is high 2092km World renowned The highest Central in the world for mountain priority for the of coastline for its hospitality geographical Oman At A Glance visitors Omani Government range in GCC location Perched on the southeast coast of the Arabian Peninsula and located within a 7-hour flight of 50% of the world, the Sultanate of Oman is easily accessible. All international participants will need to fly to Muscat International Airport, which is located in the north west of the city and approximately 100 km from Al Mussanah Sports City. Safety In 2020 Oman was ranked the 5th safest country in the world for visitors. Known for the incredible hospitality of the Omani people, all visitors are welcomed with open arms for an experience you will never forget. Muscat Weather Oman is known for its tropical climate whilst still subject to seasonal changes. From October through to April, the Sultanate offers a lovely climate, with an average temperature of 23°C. Currency Omani Rials and Omani Baisas (1000 baisas equals 1 Omani Rial) 1 OMR = $2.6 USD. The currency is pegged to the USD, offering a stable exchange rate. Currency exchange services are available at the Muscat International Airport and currency exchange bureaus are present in most shopping malls and hotels. -

ANNEX a to the 1998 FX and CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED and RESTATED AS of NOVEMBER 19, 2017 I

ANNEX A to the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions _________________________ Amended and Restated November 19, 2017 Amended March 16, 2020 INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. EMTA, INC. TRADE ASSOCIATION FOR THE EMERGING MARKETS Copyright © 2000-2020 by INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. EMTA, INC. ISDA and EMTA consent to the use and photocopying of this document for the preparation of agreements with respect to derivative transactions and for research and educational purposes. ISDA and EMTA do not, however, consent to the reproduction of this document for purposes of sale. For any inquiries with regard to this document, please contact: INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. 10 East 53rd Street New York, NY 10022 www.isda.org EMTA, Inc. 405 Lexington Avenue, Suite 5304 New York, N.Y. 10174 www.emta.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION TO ANNEX A TO THE 1998 FX AND CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED AND RESTATED AS OF NOVEMBER 19, 2017 i ANNEX A CALCULATION OF RATES FOR CERTAIN SETTLEMENT RATE OPTIONS SECTION 4.3. Currencies 1 SECTION 4.4. Principal Financial Centers 6 SECTION 4.5. Settlement Rate Options 9 A. Emerging Currency Pair Single Rate Source Definitions 9 B. Non-Emerging Currency Pair Rate Source Definitions 21 C. General 22 SECTION 4.6. Certain Definitions Relating to Settlement Rate Options 23 SECTION 4.7. Corrections to Published and Displayed Rates 24 INTRODUCTION TO ANNEX A TO THE 1998 FX AND CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED AND RESTATED AS OF NOVEMBER 19, 2017 Annex A to the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions ("Annex A"), originally published in 1998, restated in 2000 and amended and restated as of the date hereof, is intended for use in conjunction with the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions, as amended and updated from time to time (the "FX Definitions") in confirmations of individual transactions governed by (i) the 1992 ISDA Master Agreement and the 2002 ISDA Master Agreement published by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association, Inc. -

S.No State Or Territory Currency Name Currency Symbol ISO Code

S.No State or territory Currency Name Currency Symbol ISO code Fractional unit Abkhazian apsar none none none 1 Abkhazia Russian ruble RUB Kopek Afghanistan Afghan afghani ؋ AFN Pul 2 3 Akrotiri and Dhekelia Euro € EUR Cent 4 Albania Albanian lek L ALL Qindarkë Alderney pound £ none Penny 5 Alderney British pound £ GBP Penny Guernsey pound £ GGP Penny DZD Santeem ﺩ.ﺝ Algeria Algerian dinar 6 7 Andorra Euro € EUR Cent 8 Angola Angolan kwanza Kz AOA Cêntimo 9 Anguilla East Caribbean dollar $ XCD Cent 10 Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar $ XCD Cent 11 Argentina Argentine peso $ ARS Centavo 12 Armenia Armenian dram AMD Luma 13 Aruba Aruban florin ƒ AWG Cent Ascension pound £ none Penny 14 Ascension Island Saint Helena pound £ SHP Penny 15 Australia Australian dollar $ AUD Cent 16 Austria Euro € EUR Cent 17 Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN Qəpik 18 Bahamas, The Bahamian dollar $ BSD Cent BHD Fils ﺩ.ﺏ. Bahrain Bahraini dinar 19 20 Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka ৳ BDT Paisa 21 Barbados Barbadian dollar $ BBD Cent 22 Belarus Belarusian ruble Br BYR Kapyeyka 23 Belgium Euro € EUR Cent 24 Belize Belize dollar $ BZD Cent 25 Benin West African CFA franc Fr XOF Centime 26 Bermuda Bermudian dollar $ BMD Cent Bhutanese ngultrum Nu. BTN Chetrum 27 Bhutan Indian rupee ₹ INR Paisa 28 Bolivia Bolivian boliviano Bs. BOB Centavo 29 Bonaire United States dollar $ USD Cent 30 Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark KM or КМ BAM Fening 31 Botswana Botswana pula P BWP Thebe 32 Brazil Brazilian real R$ BRL Centavo 33 British Indian Ocean -

1 Executive Summary Oman's Investment Climate Is Conducive To

Executive Summary Oman’s investment climate is conducive to U.S. investment. Omani officials and businesspeople generally value U.S. technology, skills, and expertise in a wide range of fields, appreciate U.S. firms’ reputation for reliable, transparent business practices, and are keen to leverage U.S. business models, corporate values, and entrepreneurial culture in order to take fuller advantage of the United States-Oman Free Trade Agreement (FTA). American firms enjoy special privileges under the FTA, namely duty exemptions, national treatment, and non-discrimination in government procurement. However, persistent lack of compliance by Omani Customs to FTA Article 4 regarding duty exemption for eligible U.S. goods transshipped by road via Dubai as well as the imposition of a new “In Country Value” program, as of January 1, 2014, promoting local sourcing in the oil and gas sector, remain areas of concern in an otherwise positive operating environment for U.S. investors. In addition, mandatory Omanization hiring quotas for Omani nationals and scarcity of gas for new manufacturing projects posed challenges for U.S. investors. Advantages of investing in Oman include: Oman’s business-friendly environment, including the U.S.-Oman Free Trade Agreement; a modern business law framework; respect for free markets, contract sanctity, and property rights; relatively low taxes; and a one-stop-shop at the Ministry of Commerce and Industry for business registration; The educated and largely bilingual Omani work force; The excellent quality of life: