Eastern & Western Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mongolian Big Dipper Sūtra

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 29 Number 1 2006 (2008) The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies (ISSN 0193-600XX) is the organ of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, Inc. It welcomes scholarly contributions pertaining to all facets of Buddhist Studies. EDITORIAL BOARD JIABS is published twice yearly, in the summer and winter. KELLNER Birgit Manuscripts should preferably be sub- KRASSER Helmut mitted as e-mail attachments to: Joint Editors [email protected] as one single file, complete with footnotes and references, BUSWELL Robert in two different formats: in PDF-format, and in Rich-Text-Format (RTF) or Open- CHEN Jinhua Document-Format (created e.g. by Open COLLINS Steven Office). COX Collet GÓMEZ Luis O. Address books for review to: HARRISON Paul JIABS Editors, Institut für Kultur - und Geistesgeschichte Asiens, Prinz-Eugen- VON HINÜBER Oskar Strasse 8-10, AT-1040 Wien, AUSTRIA JACKSON Roger JAINI Padmanabh S. Address subscription orders and dues, KATSURA Shōryū changes of address, and UO business correspondence K Li-ying (including advertising orders) to: LOPEZ, Jr. Donald S. Dr Jérôme Ducor, IABS Treasurer MACDONALD Alexander Dept of Oriental Languages and Cultures SCHERRER-SCHAUB Cristina Anthropole SEYFORT RUEGG David University of Lausanne CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland SHARF Robert email: [email protected] STEINKELLNER Ernst Web: www.iabsinfo.net TILLEMANS Tom Fax: +41 21 692 30 45 ZÜRCHER Erik Subscriptions to JIABS are USD 40 per year for individuals and USD 70 per year for libraries and other institutions. For informations on membership in IABS, see back cover. -

Early Daoist Meditation and the Origins of Inner Alchemy

EARLY DAOIST MEDITATION 7 EARLY DAOIST MEDITATION AND THE ORIGINS OF INNER ALCHEMY Fabrizio Pregadio According to one of the scriptures belonging to the Taiqing, or Great Clar- ity, tradition, after an adept receives alchemical texts and relevant oral instructions from his master, he withdraws to a mountain or a secluded place to perform purification practices. He establishes the ritual area, demar- cates it with talismans for protection against demons and wild animals, and builds a Chamber of the Elixirs (danshi) at the centre of this protected space. To start compounding the elixir, he chooses a favourable day based on traditional methods of calendrical computation. When all ritual, spatial and temporal conditions are fulfilled, he may finally kindle the fire. Now he offers food and drink to three deities, and asks that they grant the successful compounding of the elixir: This petty man, (name of the adept), truly and entirely devotes his thoughts to the Great Lord of the Dao, Lord Lao and the Lord of Great Harmony. Alas! This petty man, (name of the adept), covets the Medicine of Life! Lead him so that the Medicine will not volat- ilise and be lost, but rather be fixed by the fire! Let the Medicine be good and efficacious, let the transmutations take place without hesitation, and let the Yellow and the White be entirely fixed! When he ingests the Medicine, let him fly as an immortal, have audience at the Purple Palace (Zigong), live an unending life and become an accomplished man (zhiren)!1 The Great Lord of the Dao (Da Daojun), Lord Lao (Laojun, or Laozi in his divine aspect) and the Lord of Great Harmony (Taihe jun) are not mentioned together in other alchemical texts. -

Wushu * Tai Chi * Kung Fu * Qigong and Education About Wushu, in All Its Forms

V O L . 02 NO. 03 JULY QUARTERLY AUGUST JOURNAL OF WUSHU SEPTEMBER IN AUSTRALIA Wushu Herald 2014 ISSN 2202-8137 (Print) ISSN 2203-6067 (Online) What’s inside Australian Our community news Wushu Calendar events Community From the Board Portal World news The Wushu Herald is our Golden Dragon, Hong Kong contribution to the Wushu community in Australia. We hope that it will continue to be the source of information Wushu * Tai Chi * Kung Fu * Qigong and education about Wushu, in all its forms. As a platform for Dear Wushu and Tai Chi practitioners, sharing thoughts, ideas, Welcome to the third issue of the second volume Following our discussion of Wushu in the experiences and achievements (2014) of The Wushu Herald! Olympics, we have briefly covered the Nanjing Youth Olympic Games 2014 where a Wushu it will foster open discussion, tournament was held. facilitate the finding of common Our journal aims to share with you the most Qigong practitioners from all over the world had current Wushu, Tai Chi and Qigong news from ground and help us all grow an opportunity to upgrade their skills by Australia and overseas. participating in the annual exchange and stronger together. The current issue is available to members online tournament organized by the International from the website (www.wushu-council.com.au) Qigong Association. This year it was held in and printed copies can be purchased. China for the first time near the Jiuhua Mountain famous for the Temple on top of it attracting By joining the state associations of the Wushu pilgrims wanting to make “A Big Wish” under the Council Australia as members and subscribing special tree. -

The Seal of the Unity of the Three SAMPLE

!"# $#%& '( !"# )*+!, '( !"# !"-## By the same author: Great Clarity: Daoism and Alchemy in Early Medieval China (Stanford University Press, 2006) The Encyclopedia of Taoism, editor (Routledge, 2008) Awakening to Reality: The “Regulated Verses” of the Wuzhen pian, a Taoist Classic of Internal Alchemy (Golden Elixir Press, 2009) Fabrizio Pregadio The Seal of the Unity of the Three A Study and Translation of the Cantong qi, the Source of the Taoist Way of the Golden Elixir Golden Elixir Press This sample contains parts of the Introduction, translations of 9 of the 88 sections of the Cantong qi, and parts of the back matter. For other samples and more information visit this web page: www.goldenelixir.com/press/trl_02_ctq.html Golden Elixir Press, Mountain View, CA www.goldenelixir.com [email protected] © 2011 Fabrizio Pregadio ISBN 978-0-9843082-7-9 (cloth) ISBN 978-0-9843082-8-6 (paperback) All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Typeset in Sabon. Text area proportioned in the Golden Section. Cover: The Chinese character dan 丹 , “Elixir.” To Yoshiko Contents Preface, ix Introduction, 1 The Title of the Cantong qi, 2 A Single Author, or Multiple Authors?, 5 The Dating Riddle, 11 The Three Books and the “Ancient Text,” 28 Main Commentaries, 33 Dao, Cosmos, and Man, 36 The Way of “Non-Doing,” 47 Alchemy in the Cantong qi, 53 From the External Elixir to the Internal Elixir, 58 Translation, 65 Book 1, 69 Book 2, 92 Book 3, 114 Notes, 127 Textual Notes, 231 Tables and Figures, 245 Appendixes, 261 Two Biographies of Wei Boyang, 263 Chinese Text, 266 Index of Main Subjects, 286 Glossary of Chinese Characters, 295 Works Quoted, 303 www.goldenelixir.com/press/trl_02_ctq.html www.goldenelixir.com/press/trl_02_ctq.html Introduction “The Cantong qi is the forefather of the scriptures on the Elixir of all times. -

(Pdf) Download

Copyright © 2015 Paul J. Cote & Troy J. Price Chinese Internal Martial Arts All Rights Reserved. Tai Ji Quan Xing-Yi Quan Ba Gua Zhang Okinawa/Japan Yang Luchan Li Luoneng Dong Haichuan Karate/Kobudo/Judo Yang Banhou Liu Qilan Yin Fu Wu Quanyu Che Yizhai Cheng Tinghua Shuri-te/Naha-te Systems Yang Chengfu Guo Yunshen Liu Dekuan Konishi Yasuhiro Li Cunyi XY/BG Gima Makoto Okinawan Zhang Zhaodong XY/BG Shito-ryu/Shotokan Karate & Kobudo Sun Lutang XY/BG Yamaguchi Gogen 1st / 2nd / 3rd Japan Generation Keng Jishan XY/BG Oshiro Roy Chotoku Kyan (Shorin) Goju-ryu Jujutsu/Karate Motobu Choki (Shorin) Wang Maozhai TJ Gao Yisheng BG (3rd) Chinese Internal Hoy Yuan Ping Takashi Uechi Miyagi Chojun (Goju) Yang Yuting TJ Wu Mengxia XY/BG Martial Art/Karate Tenshi Shinjo Kempo Jutsu Shinto Yoshin-Ryu Jujutsu Taira Shinken (Kobudo) Ma Gui BG Liu Fengcai BG Tung Gee Hsing Yamada Yajui Otsuka Hironori Gao Kexing BG Zhang Junfeng XY/BG XY/Motobu Shuri-te Kodokan Judo Wado Karate Isshin-Ryu Style Han Muxia XY/BG Chen Panling XY/BG Shimabuku Tatsuo Zhao Runting XY Wang Shujin XY/BG Robert Trias Douglas Grose Father of Karate in USA Shinto Yoshin-Ryu Jujutsu Shuri-Ryu Karatedo Shin Mei Shorin-Ryu Karate Shimabuku Kichiro Wang Peisheng Hong Yixiang XY/BG Uezu Angi Yin Cheng Gong Fa Hong Yimian XY/BG John Pachivas Stuart Dorow/Carol Liskai YCGF Wu TJ/XY/BG/QG Guo Fengchih XY/BG Shuri-Ryu Karatedo Tsuyoshi Uechi Goju-Ryu Karatedo Okinawan Kobudo Robert W. Smith Jujutsu/Judo Kodokan Judo Steven Roensch Pioneer of Chinese Ridgely Abele Dane Sutton Zhang Yun Shuri-Ryu Karatedo Shinto Yoshin Kai Jujutsu Internal Martial Arts in USA Shuri-Ryu Karatedo Isshinryu Karate/Kobudo Beijing YCGF TJ/XY/BG/QG Taiwan XY/BG Shuri-Te & US Jujutsu Other Influences [PJC] Paul J. -

The Electronic Journal of East and Central Asian Religions

The electronic Journal of East and Central Asian Religions Volume 1 Autumn 2013 Contents Preface 4 Introduction 5 Friederike Assandri, Examples of Buddho–Daoist interaction: concepts of the af- terlife in early medieval epigraphic sources 1 Carmen Meinert, Buddhist Traces in Song Daoism: A Case From Thunder-Rite (Leifa) Daoism 39 Henrik H. Sørensen Looting the Pantheon: On the Daoist Appropriation of Bud- dhist Divinities and Saints 54 Cody Bahir, Buddhist Master Wuguang’s (1918–2000) Taiwanese web of the colo- nial, exilic and Han 81 Philip Garrett, Holy vows and realpolitik: Preliminary notes on Kōyasan’s early medieval kishōmon 94 Henrik H. Sørensen Buddho–Daoism in medieval and early pre-modern China: a report on recent findings concerning influences and shared religious prac- tices 109 Research Articles eJECAR 1 (2013) Buddhist Traces in Song Daoism: A Case From Thunder-Rite (Leifa) Daoism Carmen Meinert Käte Hamburg Kolleg, Ruhr-Universität Bochum Topic FTER the turn of the first millennium the Chinese religious landscape had developed A to a degree that the production of hybrid Buddho-Daoist ritual texts was a rather widespread phenomenon. With the rise of a Daoist trend referred to as Thunder Rites (leifa 雷法), which matured during the mid- to late-Song 宋 Dynasty (960–1279) and did not solely pertain to any particular branch of Daoism, a new type of (often Buddho-Daoist) ritual practice had emerged, largely exorcistic in nature and that would eventually be incorporated into classical Daoist traditions.1 Practitioners of Thunder Rites were either members of the established Daoist orthodoxy or itinerant thaumaturges, referred to as ritual masters (fashi 法師).2 They had received powerful ritual techniques (fa 法) which, by using the potency of the thunder, aimed to correct the world’s calamitous powers to regain a state of balance or harmony. -

Glosario De Artes Internas Glosario De Artes Internas

GLOSARIO DE ARTES INTERNAS www.taichichuan.com.es GLOSARIO DE ARTES INTERNAS Este glosario de artes internas chinas se empezó a elaborar en 2001 para chenretiro.com y a partir de 2004 lo seguimos editando y ampliando la redacción y los colaboradores de TAI-CHI CHUAN con los términos que van apareciendo en los artículos publicados. Esta versión incluye los términos aparecidos hasta el nº 19. Los términos chinos aparecen en primer lugar en negrita en transcripción pinyin (Taijiquan, Qigong), y a continuación en Wade-Giles (T'ai chi chüan, Ch'i kung) y / o en transcripción "castellanizada" (Tai chi chuan, Chi kung). Cuando en una entrada aparecen dos transcripciones en chino ( ), la primera es en caracteres tradicionales y la segunda en caracteres simplificados. A Almohada de jade (Yu Zhen) - Punto situado en el cruce del borde occipital con la línea central de la cabeza. Es uno de los tres puntos de la espalda donde el Qi tiende a bloquearse, y el más difícil de abrir. Por eso se conoce también por el nombre de "La puerta de hierro". An - Empujar. Una de las Ocho fuerzas. Se usa la palma de una o ambas manos para empujar al oponente con la intención de que la fuerza penetre en su cuerpo más allá del punto de contacto. Se relaciona con el trigrama Dui (lago/metal), beneficia los pulmones. An jin (An Chin) - Energía oculta. B Ba duan jin (Pa tuan chin) - Ocho piezas de un brocado de seda. Esta conocida forma de Qigong se compone de ocho ejercicios que trabajan sobre estiramientos para fortalecer músculos, tendones y todo el sistema de órganos internos y meridianos. -

THE DAOIST BODY in the LITURGY of SALVATION THROUGH REFINEMENT by BINGXIA BIAN B.L., South-Central University for Nationalities, 2016

THE DAOIST BODY IN THE LITURGY OF SALVATION THROUGH REFINEMENT by BINGXIA BIAN B.L., South-Central University for Nationalities, 2016 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Religious Studies 2019 ii This thesis entitled: The Daoist Body in the Liturgy of Salvation through Refinement written by Bingxia Bian has been approved for the Department of Religious Studies Terry F. Kleeman Loriliai Biernacki Holly Gayley Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Bian, Bingxia (M.A., Department of Religious Studies) The Daoist Body in the Liturgy of Salvation through Refinement Thesis directed by Professor Terry F. Kleeman Abstract This thesis will address the concept of the body and souls in the context of a Daoist ritual, the Liturgy of Salvation through Refinement (liandu yi 鍊度儀) based on the "Great Refinement of Numinous Treasures" (Lingbao dalian 靈寶⼤鍊) in the Great Rites of Shangqing Lingbao (Shangqing Lingbao dafa 上清灵宝⼤法) written by Wang Qizhen 王契真 (fl. ca 1250). The first chapter is a brief review of traditional Chinese ideas toward the body and souls. People believed that the deceased live in the other world having the same need as they alive. Gradually, they started to sought methods to extend their life in this world and to keep their souls alive in the other world. -

Cai Li Fo from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia (Redirected from Choy Lee Fut)

Cai Li Fo From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Choy Lee Fut) Cai Li Fo (Mandarin) or Choy Li Fut (Cantonese) (Chinese: 蔡李佛; pinyin: Cài L! Fó; Cantonese Yale: Choi3 Lei5 Fat6; Cai Li Fo aka Choy Lee Fut Kung Fu) is a Chinese martial art founded in Chinese 蔡李佛 [1] 1836 by Chan Heung (陳享). Choy Li Fut was named to Transcriptions honor the Buddhist monk Choy Fook (蔡褔, Cai Fu) who taught him Choy Gar, and Li Yau-San (李友山) who taught Mandarin him Li Gar, plus his uncle Chan Yuen-Wu (陳遠護), who - Hanyu Pinyin Cài L! Fó taught him Fut Gar, and developed to honor the Buddha and - Wade–Giles Ts'ai4 Li3 Fo2 the Shaolin roots of the system.[2] - Gwoyeu Romatzyh Tsay Lii For The system combines the martial arts techniques from various Cantonese (Yue) [3] Northern and Southern Chinese kung-fu systems; the - Jyutping Coi3 Lei5 Fat6 powerful arm and hand techniques from the Shaolin animal - Yale Romanization Kai Li Fwo forms[4] from the South, combined with the extended, circular movements, twisting body, and agile footwork that characterizes Northern China's martial arts. It is considered an Part of the series on external style, combining soft and hard techniques, as well as Chinese martial arts incorporating a wide range of weapons as part of its curriculum.[5] Choy Li Fut is an effective self-defense system,[6] particularly noted for defense against multiple attackers.[7] It contains a wide variety of techniques, including long and short range punches, kicks, sweeps and take downs, pressure point attacks, joint locks, and grappling.[8] According to Bruce Lee:[9] "Choy Li Fut is the most effective system that I've seen for fighting more than one person. -

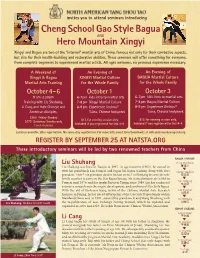

OCT XINGYI and BAGUA Event

invites you to attend seminars introducing Cheng School Gao Style Bagua AND Hero Mountain Xingyi Xingyi and Bagua are two of the “internal” martial arts of China, famous not only for their combative aspects, but also for their health-building and restorative abilities. These seminars will offer something for everyone, from complete beginners to experienced martial artists. All ages welcome, no previous experience neces sary. A Weekend of An Evening of An Evening of Xingyi Bagua XINGYI Martial Culture BAGUA Martial Culture Martial Ar&ts Training for the Whole Family for the Whole Family October 4- 6 October 1 October 3 9 am-3:30 pm 6-7 pm kids intro to martial arts 6-7 pm kids intro to martial arts Training with Liu Shuhang, 7-8 pm Xingyi Martial Culture 7-8 pm Bagua Martial Culture Li Cang and their Chinese and 8- 9 pm Experience Jinshou© 8- 9pm Experience Jinshou© American disciples. Tuina, Chinese bodywork Tuina, Chinese bodywork $200 Friday-Sunday $15 for evening session only. $175 Saturday-Sunday only $15 for evening session only. Included if you registered for Oct 4-6 Lunch included Included if you registered for Oct 4-6 Location available after registration. No same-day registration. For more info email John Groschwitz at [email protected] REGISTER BY SEPTEMBE R 25 AT NATSTA.ORG These introductory seminars will be led by two renowned teachers from China BAGUA LINEAGE: Liu Shuhang Dong Haichuan Liu Shuhang was born in Tianjin in 1947. At age fourteen (1962), he moved in 董海川 with his granduncle Liu Fengcai and began his Bagua training along with Liu’s Cheng Tinghua grandson. -

Doumu: the Mother of the Dipper

Livia Kohn DOUMU: THE MOTHER OF THE DIPPER Introduction The goddess Doumu 4- f.J:, the Mother of the Dipper, is a Daoist stellar deity of high popularity. Shrines to her are found today in many major Daoist sanctuaries, from the Qingyang gong. jf.i;inChengduA lllthrough Louguan tttfL plearXi'an iN~)to Mount Tai * t1Jin Shandong. She represents the genninal, creative power behind one of the most central Daoist constellations, the Northern Dipper, roler offates and central orderer of the universe, which is said to consist of seven or nine stars, called the Seven Primes or the Nine Perfected. 1 The Mother of the Dipper appears in Daoist literature from Yuan times onward, there is no trace of any scripture or material associated with her in Song sources or libraries. 2 Her major scripture, the Doumu jing4- f.J: ~I (translated below), survives in both the Daoist canon of 1445 and in a Ming dynasty manuscript dated to 1439. The goddess can be seen as part of a general tendency among Daoists of the Ming to include more popular and female deities into their pantheon, which in turn is related to the greater emphasis on goddesses in popular religion and Buddhism at the time. 3 In I Edward Schafer calls them the Nine Quintessences (1977, p. 233). 2 Van der Loon (1984) has no entry on any te;-.."t regarding her worship. 3 A prominent example of a popular goddess at the time is Mazu ~ 111 or Tianfei f:. 9(.. who was also adopted into the Daoist pantheon. On her development, see Wädow 1992: on her Daoist adoption, see Bohz 1986. -

ESSENCE of COMBAT SCIENCE Translated from Chinese by Andrzej Kalisz

WANG XIANGZHAI ESSENCE OF COMBAT SCIENCE Translated from Chinese by Andrzej Kalisz YIQUAN ACADEMY 2004 ....................................................................................................................................................... At beginning of 1940s Wang Xiangzhai was interviewed several times by reporters of Beijing newspapers. Those interviews in collected form were appended to many books about yiquan published in China. Here we provide English translation of this collection. ....................................................................................................................................................... Founder of dachengquan – Wang Xiangzhai, is well known in the north and in the south, praised by martial artists from all over China. Lately he moved to Beijing. He issued statement that he will wait to meet guest every Sunday afternoon from 1 p.m. to 4 p.m. in Dayangyibing hutong, in order to exchange opinions and knowledge with other martial artists, to promote and develop combat science. Our reporter visited him yesterday. Reporter You have great abilities. I admire you. Could I ask about your aspirations in combat science? Wang Xiangzhai I feel ashamed when friends introduce me as a great representative of dachengquan. Since I left my teacher in 33rd year of reign of emperor Guangxu (1907), I traveled all over country, left footprints in many places, experienced many hardships and met many famous masters. Most valuable was meeting teachers and friends, with whom I could compare skill and improve it, so if we are talking about combat science I can say that I’m “an old horse which knows way back home”. Lately Zhang Yuheng wrote several articles about me. Because I’m afraid that it could cause some misunderstandings, I would like to explain my intentions. I’m getting older, I’m not thinking about fame, but when I still can, I would like to work together with others to promote natural human potential and virtues of a warrior, to eliminate wrong teachings of those who deceive themselves and deceive others.