PROCEEDINGS of the 20Th ANNUAL MEETING - ST

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The PICKLEWORM: Its CONTROL on CUCURBITS in ALABAMA

( L.'t-. )f BULLETIN 381 SEPTEMBER 1968 The PICKLEWORM: Its CONTROL On CUCURBITS In ALABAMA SNj AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION NAI AUBURN UNIVERSITY E. V. Smith, Director Auburn, Alabama CONTENTS INTRODUCTION- - - - LIFE, HISTORY- - - - - - -__4 CONTROL METHODS EVALUATED PLANTING DATES-- INSECTICIDES----------- RESISTANT VARIETIES ____________-__ -16 SU M M A R Y ----------------------- --- 25 ACKNOWLEDGMENT__-__-__________ -------- -2 6 LITERATURE CITED --------------- 27 PHOTO CREDITS. Figures 1A, iB, and iC were supplied by Dupree et al (3), University of Georgia Agricultural Experiment Station. Other photos supplied by the authors. FIRST PRINTING 3M, SEPTEMBER 1968 The PICKLEWORM: Its CONTROL on CUCURBITS in ALABAMA T. DON CANERDAY, Assistant Professor of Entomology-Zoology* JAMES D. DILBECK, Graduate Assistant of Entomology-Zoology INTRODUCTION THE PICKLEWORM, Diaphanianitidalis (Stoll), is the most de- structive insect pest of cucurbits in Alabama. This insect regularly causes serious damage in the South Atlantic and Gulf States and occasionally as far west as Oklahoma and Nebraska and as far north as Iowa and Connecticut. It has also been reported from Canada, Puerto Rico, Panama, Brazil, Colombia, French Guiana, and Peru (3). Cantaloupe, cucumber, and summer squash are primary host plants of the pickleworm in Alabama. Maximum yields of these crops in summer and fall are deterred by the pickleworm. Gourds, pumpkins, and watermelons are also occasionally attacked. The larva reduces plant vigor and destroys market value of the crop by feeding on buds, flowers, vines, stalks, and fruits. Walsh and Riley (8) gave the first account of pickleworm injury in the United States in 1869. Investigations on the insect were begun in 1899 by Quaintance (1901) in Georgia. -

Melonworm, Diaphania Hyalinata Linnaeus (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Crambidae)1 John L

EENY163 Melonworm, Diaphania hyalinata Linnaeus (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Crambidae)1 John L. Capinera2 Distribution about 0.7 mm in length and 0.6 mm in width. Hatching occurs after 3–4 days. Melonworm, Diaphania hyalinata Linnaeus, occurs throughout most of Central and South America and the Caribbean. It also has been reported from Africa (Mohaned et al. 2013). The United States is the northern limit of its permanent range, and wintertime occurrence generally is limited to south Florida and perhaps south Texas. Melon- worm disperses northward annually. Its distribution during the summer months is principally the southeastern states, though occasionally it disperses north to New England and the Great Lakes region. Life Cycle and Description The melonworm can complete its life cycle in about 30 days. It is present throughout the year in southern Florida, where it is limited mostly by availability of host plants. It disperses northward annually, usually arriving in northern Florida in Figure 1. Eggs and newly hatched larva of melonworm, Diaphania June and other southeastern states in July, where no more hyalinata Linnaeus, on foliage. than three generations normally occur before cold weather Credits: Rita Duncan, UF/IFAS kills the host plants. Larva Egg There are five instars. Total larval development time is about 14 days, with mean (range) duration of the instars Melonworm moths deposit oval, flattened eggs in small about 2.2 (2-3), 2.2 (2-3), 2.0 (1-3), 2.0 (1-3), and 5.0 (3-8) clusters, often averaging two to six overlapping eggs per days, respectively. Head capsule widths are about 0.22, 0.37, egg mass. -

Vegetable Pests Pickleworm

W206 Pickleworm Frank A. Hale, Professor; Carla Dilling, Graduate Research Assistant; and Jerome F. Grant, Professor, Entomology and Plant Pathology The pickleworm, Diaphania nitidalis (Stoll) (Fam- Figure 1. Pickleworm larvae, adult, pupa and egg (enlarged) ily Crambidae, previously Pyralidae), is found from (Images courtesy of North Carolina Cooperative Extension Service). Canada into parts of South America, and as far west as Oklahoma and Nebraska. It is an important pest of numerous cucurbits. Summer squash is the preferred host, but it also feeds on cantaloupe, cucumber, pump- kin and winter squash. Late-planted cantaloupes are heavily attacked in some areas. Damage The destructive stage of this insect is the larval stage. Larvae feed on, and tunnel into, the flowers, vines and fruits. Young larvae usually feed on internal portions of blossoms, leaf buds or growing tips of vines. Older larvae, on the other hand, will bore into the fruit of the plant, depositing excrement (frass) as they feed and move throughout the fruit. Damaged fruit usually sours, spoils and rots. Vine damage occurs when larvae bore into the vine, preventing its growth and causing its ultimate death. Numerous feeding holes may be found along the vines. In the Southeastern United States, damage from pickleworms is not usually seen until late August or early September. Description and Life Cycle Adults are small moths with a wingspan of about 1¼ inches and a large, light-colored to yellow spot near the center of each dark-colored forewing. The tip of the abdomen contains a cluster of brush-like hairs. The small, white to pale-colored eggs are laid singly or in small clusters directly on the foliage. -

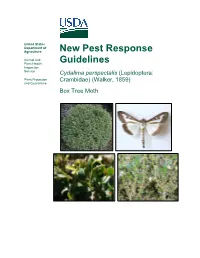

New Pest Response Guidelines

United States Department of Agriculture New Pest Response Animal and Plant Health Guidelines Inspection Service Cydalima perspectalis (Lepidoptera: Plant Protection Crambidae) (Walker, 1859) and Quarantine Box Tree Moth The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. The opinions expressed by individuals in this report do not necessarily represent the policies of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Mention of companies or commercial products does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture over others not mentioned. USDA neither guarantees nor warrants the standard of any product mentioned. Product names are mentioned solely to report factually on available data and to provide specific information. This publication reports research involving pesticides. All uses of pesticides must be registered by appropriate state and/or federal agencies before they can be recommended. -

Six Steps to Successful Pest Management

PEST IDENTIFICATION PMA 4570/6228 Lab 2 June 29, 2017 Steps towards a successful IPM program 1. Correct identification 2. Monitoring 3. Economic thresholds 4. Choice of optimum pest control option Pests Pest – organism that interferes with the availability, quality, or value of a managed resource; conflicts with human needs or values Key – perennial pest, causes major losses Secondary – minor pest, kept in check by natural enemies Occasional – infrequent damage Insects as Pests ~1,000,000 species of insects have been described ~1% (10,000) could be considered serious (key) pests ~1,000 occasional pests > $40 bill on pesticides worldwide, $12 bill in US This does not include costs for cultural or biological control practices!! Injury vs. Damage Injury the affect of pest activities on the host Bites, feeding, stings, vectors of disease Direct or Indirect injury Damage the monetary loss as a result of pest injury Direct Injury Injury caused to the marketable parts of the crop Corn earworm, Helicoverpa zea Pickleworm, Diaphania nitidalis feeding in squash feeding on sweet corn Western flower thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis CAB Tomato spotted wilt virus International J. Thomas Indirect Injury Injury caused to the non-marketable parts of the crop Beet armyworm, Spodoptera exigua Blueberry leaf beetle, Colaspis pseudofavosa Flea beetle Umn.edu Melon aphids on squash, Aphis gossypii The wealth of information gained from correct pest identification Life cycle - damaging life stages, life span, growth requirements Injury symptoms and when (stage) crop most severely affected Identify natural enemies Understand environmental conditions and management practices that impact the pest Leaf miner on Spider tomato mites Insect Key Features - Wings Elytron Hemelytra Coleoptera Hemiptera Wings Lepidoptera Diptera Hymenoptera Thysanoptera Insect Key Feature - Mouthparts chewing siphoning beak biting sponging Piercing-sucking Pest identification can be complicated! Sexual dimorphism Spotted Wing Drosophila female Spotted Wing Drosophila male Photos by L. -

John L. Capinera Chairman and Professor

John L. Capinera Chairman and Professor Contact: Building 970, Natural Area Dr. Gainesville, FL 32611 (352) 273-3905 [email protected] Education (30% Research, 20% Extension, 50% Teaching) Ph.D., University of Massachusetts (Entomology), 1976 M.S., University of Massachusetts (Entomology), 1974 B.A., Southern Connecticut State University (Biology), 1970 Employment Professor and Chairman (1987-present), University of Florida Professor and Head (1985-1987) Colorado State University Professor and Interim Chair (1983-1985), Colorado State University Associate Professor (1981-1985), Colorado State University Assistant Professor (1976-1981), Colorado State University Administrative Responsibilities Responsible for administration of teaching, research, and extension functions of 30 faculty, 30 full-time staff, about 140 graduate students, and 40 undergraduate students in Gainesville. Provide disciplinary support for 40 faculty at research and education centers statewide. Represent discipline to state agencies, commodity groups, and general public. Research Habitat associations and host plant relations of grasshoppers. Development of management practices for insect pests. Biology and management of terrestrial snail and slugs Teaching ENY 5236, Insect Pest and Vector Management ENY 4210/5212, Insects and Wildlife ENY 4161/6166 Insect Classification Selected Publications Books Capinera, J.L., C.W. Scherer, and J.M. Squitier. 2001. Grasshoppers of Florida. University Press of Florida, Gainesville. 143 pp. Capinera, J.L. 2001. Handbook of Vegetable Pests. Academic Press, New York. 729 pp. Capinera, J.L. (editor). 2004. Encyclopedia of Entomology. Vols. 1-3. Kluwer Academic Press, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. 2580 pp. Capinera, J.L., R. Scott, and T.J. Walker. 2004. Field Guide to Grasshoppers, Katydids and Crickets of the United States and Canada. -

Endosulfan: Its Isomers and Metabolites in Commercially Aquatic Organisms from the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean

Journal of Agricultural Science; Vol. 8, No. 1; 2016 ISSN 1916-9752 E-ISSN 1916-9760 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Endosulfan: Its Isomers and Metabolites in Commercially Aquatic Organisms from the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Gabycarmen Navarrete-Rodríguez1, Cesáreo Landeros-Sánchez1, Alejandra Soto-Estrada1, María del Refugio Castañeda-Chavez3, Fabiola Lango-Reynoso3, Arturo Pérez-Vazquez1 & Iourii Nikolskii G.2 1 Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus Veracruz, Veracruz-Xalapa, Manlio Fabio Altamirano, Veracruz, México 2 Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus Montecillo, Montecillo, Texcoco, Estado de México, México 3 Instituto Tecnológico de Boca del Río, Carretera Veracruz, Boca del Río, Veracruz, México Correspondence: Cesáreo Landeros-Sánchez, Colegio de Postgraduados Campus Veracruz, Km. 88.5 Carr Fed. Xalapa-Veracruz, vía Paso de Ovejas entre Puente Jula y Paso San Juan, Tepetates, Veracruz C.P. 91690, México. Tel: 229-201-0770 ext. 64325. E-mail: [email protected] Received: September 17, 2015 Accepted: October 26, 2015 Online Published: December 15, 2015 doi:10.5539/jas.v8n1p8 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jas.v8n1p8 Abstract The organochlorine pesticide endosulfan is an insecticide and acaricide used on a variety of crops around the world. Its adverse effects on public health and aquatic biota have been widely documented in several studies, which are closely related to their primary route of exposure, by eating food contaminated with this compound. Therefore, it is necessary to concentrate the information in order to analyze and understand its impact on public health. The present objective is to review the characteristics of endosulfan, its isomers and their presence in aquatic organisms of commercial importance in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean. -

Diaphania Nitidalis (Stoll) *Non-Rep*

Keys About Fact Sheets Glossary Larval Morphology References << Previous fact sheet Next fact sheet >> CRAMBIDAE - Diaphania nitidalis (Stoll) *Non-Rep* Taxonomy Click here to download this Fact Sheet as a printable PDF Pyraloidea: Crambidae: Spilomelinae: Diaphania nitidalis (Stoll) Common names: pickleworm Synonyms: Diaphania vitralis Larval diagnosis (Summary) Fig. 1: Late instar, lateral view Genal spot is present SV group on A1 is bisetose Mandible lacks an outer tooth (projection) Crochets on A3-6 in a mesal penellipse No black spot posterior to the SD2 seta on the prothorax Early instars have pigmented pinacula and a thick dark oval on the prothoracic shield Fig. 2: Mid-instar, lateral view Late instars have pale pinacula and an unmarked prothoracic shield Host/origin information Diaphania nitidalis is commonly intercepted on Cucumis, Cucurbita, and Sechium (cultivated cucurbits; Cucurbitaceae) from Central America. More than 93% of the interception records in PestID are from the following origin/host combinations: Fig. 3: Early instar, lateral view Origin Host(s) Costa Rica Sechium Dominican Republic Coccinea, Cucurbita, Sechium Guatemala Cucurbita, Sechium Haiti Cucurbita, Sechium Honduras Cucumis Mexico Cucumis, Cucurbita, Sechium Recorded distribution Diaphania nitidalis is distributed throughout the New World tropics. Individuals move into Fig. 4: Head and thorax; note genal spot temperate areas during the summer but are unlikely to overwinter outside of tropical or subtropical regions. This species is also found in Hawaii. Identifcation authority (Summary) Origin and host are important information for making positive identifications of this species. There are no confirmed records of D. nitidalis outside of the New World (and Hawaii), so identifications should be restricted to larvae originating from these locations on cultivated cucurbits. -

Diaphania Nitidalis and Diaphania Hyalinata, Pickleworm and Melonworm Moths (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) Leonardo D

Diaphania nitidalis and Diaphania hyalinata, Pickleworm and Melonworm Moths (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) Leonardo D. Salgado, Forest Huval, T.E. Reagan and Chris Carlton Description The genus Diaphania includes two pest species in Louisiana that affect crops in the cucumber family (Cucurbitaceae), which includes squash, zucchini, mirliton (in south Louisiana), pumpkin, gourd, cucuzzi, cantaloupe, cushaw, luffa and cucumber. Adults of both species are similar in size, with wingspans of 1.25 inches (32 mm) when fully spread. The forewings of pickleworm moths are mainly dark brown with a yellow spot near the middle. The Left: Melonworm larvae (Alton N. Sparks Jr., University hindwings are mainly yellow, bordered by brown. Wings of Georgia, Bugwood.org). Right: Pickleworm larvae (Clemson University-USDA Cooperative Extension Slide of melonworm adults are mainly silvery white with broad, Series, Bugwood.org). brown borders. Melonworm larvae are pale green with two white dorsal stripes and measure 0.8 inch to 1 inch (20 to Newly hatched caterpillars usually feed on the 25 mm) in length when fully developed. Pickleworm larvae undersides of new leaves. Melonworms feed principally are similar in shape and size of the melonworm larvae, but on leaves as they mature. However, if available leaves are differ in coloration. They are yellowish with several dark or minimal, or the plant is of a less preferred species such as brown spots distributed along the body. cantaloupe, larvae may feed on the surface of the fruit or even bore into the fruit. Blossoms are favorite feeding sites for pickleworm caterpillars, especially young larvae. Larvae may complete their development without boring into the fruit by moving among blossoms if enough are available. -

Natural Biological Control of Lepidopteran Pests by Ants

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Portal de Periódicos Eletrônicos da Universidade Estadual... 1389 Natural Biological Control of Lepidopteran Pests by Ants by Rodrigo Soares Ramos1, Marcelo Coutinho Picanço1*, Paulo Antônio Santana Júnior1, Ézio Marques da Silva2, Leandro Bacci3, Alfredo Henrique Rocha Gonring4 & Gerson Adriano Silva5 ABSTRACT The predatory ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidade) are social insects and im- portant natural enemies of pests in agroecosystems. Despite the importance of these predators, little is known about their role, especially in tropical regions. Among the major Lepidopteran pests of vegetables are Ascia monuste (Pieri- dae), Diaphania nitidalis (Crambidae), Neoleucinodes elegantalis (Crambidae) and Tuta absoluta (Gelechiidae). Thus, this work aimed to study the natural biological control of A. monuste, D. nitidalis, N. elegantalis and T. absoluta by ants. For this, we evaluated the natural biological control of A. monuste on kale and D. nitidalis on cucumber both species in the dry season. Whilst the natural biological control of N. elegantalis and T. absoluta on tomato plants were evaluated in the rainy and dry seasons. Ants preyed on Lepidoptera in the pupa stadium. They also preyed on eggs of D. nitidalis. The activity of predatory ants occurred mainly during the night. The ants were the main causes of pupae mortality of A. monuste, D. nitidalis and T. absoluta. Beyond the ants, the physiological disturbances and birds were also important factors of pupae mortality of N. elegantalis. The antsLabidus coecus and Solenopsis sp. were observed preying on pupae whereas the Paratrechina sp. was observed preying eggs of D. -

CGC 2 (1979) Cucurbit Genetics Cooperative

CGC 2 (1979) Cucurbit Genetics Cooperative Report No. 2 July 1979 Table of Contents (article titles linked to html files) Introduction Resolution and Acknowledgment Report of Second Annual Meeting Announcement of Third Annual Meeting Comments Announcement of Cucurbit Related Meetings Erratum Cucumber (Cucumis sativus) 1. The effects of illumination, explant position, and explant polarity on adventitious bud formation in vitro of seedling explants of Cucumis sativus L. cv. 'Hokus' J.B.M. Custers and L.C. Buijs (The Netherlands) CGC 2:2-4 (1979) 2. Breeding glabrous cucumber varieties to improve the biological control of the glasshouse whitefly O.M.B. de Ponti (The Netherlands) CGC 2:5 (1979) 3. Development and release of breeding lines of cucumber with resistance to the twospotted spider mite, Tetranychus urticae Koch O.M.B. de Ponti (The Netherlands) CGC 2:6-7 (1979) 4. Linkage of bacterial wilt resistance and sex expression genes in cucumber A.F. Iezzoni and C.E. Peterson (USA) CGC 2:8 (1979) 5. The influence of temperature on powdery mildew resistance in cucumber H.M.Munger (USA) CGC 2:9 (1979) 6. Dominant genes for resistance to powdery mildew in cucumber H.M. Munger, Abad Morales and Sadig Omara (USA) CGC 2:10 (1979) 7. Interspecific grafting to promote flowering in Cucumis hardwickii J. Nienhuis and R.L. Lower (USA) CGC 2:11-12 (1979) 8. Low temperature adapted slicing cucumbers release A.P.M. den Nijs (The Netherlands) CGC 2:13 (1979) 9. Silver compounds inducing male flowers in gynoecious cucumbers A.P.M. den Nijs and D.L. -

Pickleworm, Diaphania Nitidalis (Stoll) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Crambidae)1 John L

EENY164 Pickleworm, Diaphania nitidalis (Stoll) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Crambidae)1 John L. Capinera2 Distribution spherical to flattened. Their color is white initially, but changes to yellow after about 24 hours. The eggs are distrib- Pickleworm is a tropical insect that routinely survives the uted in small clusters, usually two to seven per cluster. They winter only in south Florida and perhaps south Texas. Pena are deposited principally on the buds, flowers, and other et al. (1987a) documented the overwintering biology in actively growing portions of the plant. Hatching occurs in south Florida, but overwintering has been observed as far about four days (Smith 1911). Elsey (1980) estimated egg north as Sanford, in central Florida, during mild winters. production to be 300–400 eggs per female. Pickleworm is highly dispersive, and invades much of the southeast each summer. North Carolina and South Carolina Larva regularly experience crop damage by pickleworm, but often this does not occur until August or September. In contrast, There are five instars. Total larval development time northern Florida is flooded with moths each year in early averages 14 days. Mean duration (range) of each instar is June as warm, humid tropical summer weather conditions about 2.5 (2–3), 2 (1–3), 2 (1–3), 2.5 (2–3), and 5 (4–7) become firmly established. Although it regularly takes one days, respectively. Head capsule widths for the five instars or two months for the dispersing pickleworms to move are about 0.25, 0.42, 0.75, 1.12, and 1.65 mm, respectively north from Florida to the Carolinas, in some years they (Smith et al.