Prince in the Early 80S: Considerations on the Structural Functions of Performative Gestures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Partyman by Title

Partyman by Title #1 Crush (SCK) (Musical) Sound Of Music - Garbage - (Musical) Sound Of Music (SF) (I Called Her) Tennessee (PH) (Parody) Unknown (Doo Wop) - Tim Dugger - That Thing (UKN) 007 (Shanty Town) (MRE) Alan Jackson (Who Says) You - Can't Have It All (CB) Desmond Decker & The Aces - Blue Oyster Cult (Don't Fear) The - '03 Bonnie & Clyde (MM) Reaper (DK) Jay-Z & Beyonce - Bon Jovi (You Want To) Make A - '03 Bonnie And Clyde (THM) Memory (THM) Jay-Z Ft. Beyonce Knowles - Bryan Adams (Everything I Do) I - 1 2 3 (TZ) Do It For You (SCK) (Spanish) El Simbolo - Carpenters (They Long To Be) - 1 Thing (THM) Close To You (DK) Amerie - Celine Dion (If There Was) Any - Other Way (SCK) 1, 2 Step (SCK) Cher (This Is) A Song For The - Ciara & Missy Elliott - Lonely (THM) 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) (CB) Clarence 'Frogman' Henry (I - Plain White T's - Don't Know Why) But I Do (MM) 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New (SF) Cutting Crew (I Just) Died In - Coolio - Your Arms (SCK) 1,000 Faces (CB) Dierks Bentley -I Hold On (Ask) - Randy Montana - Dolly Parton- Together You And I - (CB) 1+1 (CB) Elvis Presley (Now & Then) - Beyonce' - There's A Fool Such As I (SF) 10 Days Late (SCK) Elvis Presley (You're So Square) - Third Eye Blind - Baby I Don't Care (SCK) 100 Kilos De Barro (TZ) Gloriana (Kissed You) Good - (Spanish) Enrique Guzman - Night (PH) 100 Years (THM) Human League (Keep Feeling) - Five For Fighting - Fascination (SCK) 100% Pure Love (NT) Johnny Cash (Ghost) Riders In - The Sky (SCK) Crystal Waters - K.D. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Il Jazz Nel Veneto: Tre Modelli Di Organizzazione Artistica Nel Territorio

UNIVERSITA' CA'FOSCARI DI VENEZIA CORSO DI LAUREA IN ECONOMIA E GESTIONE DELLE ARTI E DELLE ATTIVITA' CULTURALI TESI DI LAUREA IL JAZZ NEL VENETO: TRE MODELLI DI ORGANIZZAZIONE ARTISTICA NEL TERRITORIO Relatore: DANIELE GOLDONI Correlatore: PAOLO CECCHI Laureando: LEONARDO LANZA Matricola: 818725 ANNO ACCADEMICO 2013/2014 INDICE Introduzione I CAPITOLO 1. Il Principi improvvisativi del jazz 1.1 Processi improvvisativi pag. 7 1.2 Descrizione dell'atto improvvisativo pag. 11 1.3 Improvvisazione: composizione spontanea? pag. 14 1.4 La nuova forma musicale del 900: il jazz pag. 17 II CAPITOLO 2. Tre modelli di organizzazione artistica di eventi jazz nel Veneto 2.1 Umbria Jazz: la madre di tutti i Festival jazz in Italia 2.1.1 L'importanza di Umbria Jazz per lo sviluppo dei Festival jazzistici in Italia pag. 20 2.1.2 Gli aspetti di promozione turistica e di diffusione della conoscenza della regione attraverso Umbria Jazz pag. 29 2 Indagine su tre diverse realtà del territorio veneziano 2.2 Veneto Jazz – Festival nazionale 2.2.1 La struttura organizzativa e la produzione artistica pag. 35 2.3 Vincenza Jazz – Festival territoriale 2.3.1 “New Conversation Vicenza Jazz” - La storia del Festival dal 1996 al 2012 pag. 51 2.3.2 La struttura organizzativa di “New Conversations – Vicenza Jazz” pag. 53 2.3.3 I luoghi e gli spazi riservati alla manifestazione artistica pag. 55 2.4 Caligola – Associazione culturale per il jazz nel territorio 2.4.1 Caligola: storia, obiettivi e produzioni artistiche nel corso degli anni pag. 64 2.4.2 La differenza tra l'attività artistica di Caligola e quella di un Festival jazz pag. -

Musicologie E Culture

Musicologie e culture 1 Direttore Vincenzo Caporaletti Università degli Studi di Macerata Comitato scientifico Maurizio Agamennone Università degli Studi di Firenze Fabiano Araújo Costa Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória (Br) Laurent Cugny Sorbonne Université, IReMus, Paris Fabrizio Emanuele Della Seta Università degli Studi di Pavia Michela Garda Università degli Studi di Pavia Francesco Giannattasio Sapienza – Università di Roma Giovanni Giuriati Sapienza – Università di Roma Stefano La Via Università degli Studi di Pavia Raffaele Pozzi Università degli Studi Roma Tre Musicologie e culture 1 La collana si propone come una piattaforma ideale per un dialogo tra la pluralità di approcci, metodologie, epistemologie musicologiche, senza preclusione quanto agli oggetti di studio, ai testi, alle pratiche, ai repertori, sia nella dimensione diacronica che sincronica, superando distinzioni disciplinari che appaiono sempre più inadatte a rappresentare il campo discorsivo contemporaneo sul “suono umanamente organizzato”. Vincenzo Caporaletti Introduzione alla teoria delle musiche audiotattili Un paradigma per il mondo contemporaneo www.aracneeditrice.it [email protected] Copyright © MMXIX Gioacchino Onorati editore S.r.l. – unipersonale via Vittorio Veneto, 20 00020 Canterano (RM) (06) 45551463 isbn 978-88-255-2091-0 I diritti di traduzione, di memorizzazione elettronica, di riproduzione e di adattamento anche parziale, con qualsiasi mezzo, sono riservati per tutti i Paesi. Non sono assolutamente consentite le fotocopie senza il permesso scritto dell’Editore. I edizione: gennaio 2019 Indice 3 Prefazione Parte I Teorie 7 Capitolo I La teoria delle musiche audiotattili. I concetti essenziali 1.1. Perché una teoria delle musiche audiotattili, 7 – 1.2. TMA: presupposti epi- stemologici, 15 – 1.2.1. L’approccio mediologico. -

The Purple Xperience - Biography

THE PURPLE XPERIENCE - BIOGRAPHY Hailing from Minneapolis, Minnesota, The Purple Xperience has been bringing the memories of Prince and The Revolution to audiences of all generations. Led by Matt Fink (a/k/a Doctor Fink, 3x Grammy Award Winner and original member of Prince and The Revolution from 1978 to 1991), The Purple Xperience imaginatively styles the magic of Prince’s talent in an uncannily unmatched fashion through its appearance, vocal imitation and multi-instrumental capacity on guitar and piano. Backed by the best session players in the Twin Cities, Matt Fink and Marshall Charloff have undoubtedly produced the most authentic re-creation of Prince and The Revolution in the world, leaving no attendee disappointed. MATT “DOCTOR” FINK Keyboardist, record producer, and songwriter Doctor Fink won two Grammy Awards in 1985 for the motion picture soundtrack album for “Purple Rain”, in which he appeared. He received another Grammy in 1986 for the album “Parade: Music from the Motion Picture ‘Under the Cherry Moon'”, the eighth studio album by Prince and The Revolution. Matt also has two American Music Awards for “Purple Rain”, which has sold over 25 million copies worldwide since its release. Doctor Fink continued working with Prince until 1991 as an early member of the New Power Generation. He was also a member of the jazz-fusion band, Madhouse, which was produced by Prince and Eric Leeds, Prince’s saxophonist. Notable work with Prince includes co-writing credits on the songs “Dirty Mind”, “Computer Blue”, “17 Days”, “America”, and “It’s Gonna Be a Beautiful Night,” as well as performing credits on the albums “Dirty Mind”, “Controversy”, “1999”, “Purple Rain”, “Around the World in a Day”, “Parade”, “Sign ‘O’ the Times”, “The Black Album”, and “Lovesexy”. -

Musicologie E Culture

Musicologie e culture 3 Direttore Vincenzo Caporaletti Università degli Studi di Macerata Comitato scientifico Maurizio Agamennone Università degli Studi di Firenze Fabiano Araújo Costa Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória (Br) Laurent Cugny Sorbonne Université, IReMus, Paris Fabrizio Emanuele Della Seta Università degli Studi di Pavia Michela Garda Università degli Studi di Pavia Francesco Giannattasio Sapienza – Università di Roma Giovanni Giuriati Sapienza – Università di Roma Stefano La Via Università degli Studi di Pavia Raffaele Pozzi Università degli Studi Roma Tre Musicologie e culture 3 La collana si propone come una piattaforma ideale per un dialogo tra la pluralità di approcci, metodologie, epistemologie musicologiche, senza preclusione quanto agli oggetti di studio, ai testi, alle pratiche, ai repertori, sia nella dimensione diacronica che sincronica, superando distinzioni disciplinari che appaiono sempre più inadatte a rappresentare il campo discorsivo contemporaneo sul “suono umanamente organizzato”. La pubblicazione è stata realizzata grazie al contributo della Fondazione Internazionale Padre Matteo Ricci di Macerata. Progetto di avvio della ricerca di dottorato dell’Università dell’Henan, n. CX3050A0250245; Progetto di avvio della ricerca post-dottorato in Cina. WANG LI MUSICA E CULTURA DELLE POPOLAZIONI MONGOLE NELLA REPUBBLICA POPOLARE CINESE L’ETNIA BARGA Prefazione di VINCENZO CAPORALETTI © isbn 979–12–5994–257–9 prima edizione roma 5 luglio 2021 Indice 11 Ringraziamenti 13 Prefazione 21 Introduzione Parte I L’etnomusicologia occidentale e quella cinese 37 Capitolo I Problemi dell’etnomusicologia cinese e le nuove prospettive et- nomusicologiche. I concetti essenziali 1.1. Le tradizioni musicali locali cinesi, 37 – 1.1.1. La musica cinese nell’antichi- tà, 40 – 1.1.2. -

Got Me Wrong

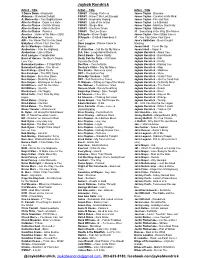

Jaykob Kendrick Artist - Title Artist - Title Artist - Title 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite CSN&Y - Change Partners James Taylor - Blossom Alabama – Dixieland Delight CSN&Y - Haven't We Lost Enough James Taylor - Carolina in My Mind A. Morissette – You Oughta Know CSN&Y - Helplessly Hoping James Taylor - Fire and Rain Alice in Chains - Down in a Hole CSN&Y - Lady of the Island James Taylor - Lo & Behold Alice in Chains - Got Me Wrong CSN&Y - Simple Man James Taylor - Machine Gun Kelly Alice in Chains - Man in the Box CSN&Y - Southern Cross James Taylor - Millworker Alice in Chains - Rooster CSN&Y - The Lee Shore JT - Something in the Way She Moves America – Horse w/ No Name ($20) D’Angelo – Brown Sugar James Taylor - Sweet Baby James Amy Winehouse – Valerie D’Angelo – Untitled (How does it JT - You Can Close Your Eyes AW – You Know That I’m No Good feel?) Jane's Addiction - Been Caught Babyface - When Can I See You Dave Loggins - Please Come to Stealing Arctic Monkeys - Arabella Boston Jason Isbell – Cover Me Up Audioslave - I Am the Highway D. Allan Coe - Call Me By My Name Jason Isbell – Super 8 Audioslave - Like a Stone D.A. Coe - Long-Haired Redneck Jaykob Kendrick - About You Avril Lavigne - Complicated David Bowie - Space Oddity Jaykob Kendrick - Barrelhouse Band of Horses - No One's Gonna Death Cab for Cutie – I’ll Follow Jaykob Kendrick - Fall Love You You into the Dark Jaykob Kendrick - Firefly Barenaked Ladies – If I had $1M Des’Ree – You Gotta Be Jaykob Kendrick - Kissing You Barenaked Ladies - One Week Destiny’s Child – Say My Name Jaykob Kendrick - Map Ben E King – Stand By Me Dire Straits - Romeo & Juliet Jaykob Kendrick - Medicine Ben Erickson - The BBQ Song DBT – Decoration Day Jaykob Kendrick - Muse Ben Harper - Burn One Down Drive-By Truckers - Outfit Jaykob Kendrick - Nuckin' Futs Ben Harper - Steal My Kisses DBT - Self-Destructive Zones Jaykob Kendrick – On the Good Foot Ben Harper - Waiting on an Angel D. -

The Ultimate Listening-Retrospect

PRINCE June 7, 1958 — Third Thursday in April The Ultimate Listening-Retrospect 70s 2000s 1. For You (1978) 24. The Rainbow Children (2001) 2. Prince (1979) 25. One Nite Alone... (2002) 26. Xpectation (2003) 80s 27. N.E.W.S. (2003) 3. Dirty Mind (1980) 28. Musicology (2004) 4. Controversy (1981) 29. The Chocolate Invasion (2004) 5. 1999 (1982) 30. The Slaughterhouse (2004) 6. Purple Rain (1984) 31. 3121 (2006) 7. Around the World in a Day (1985) 32. Planet Earth (2007) 8. Parade (1986) 33. Lotusflow3r (2009) 9. Sign o’ the Times (1987) 34. MPLSound (2009) 10. Lovesexy (1988) 11. Batman (1989) 10s 35. 20Ten (2010) I’VE BEEN 90s 36. Plectrumelectrum (2014) REFERRING TO 12. Graffiti Bridge (1990) 37. Art Official Age (2014) P’S SONGS AS: 13. Diamonds and Pearls (1991) 38. HITnRUN, Phase One (2015) ALBUM : SONG 14. (Love Symbol Album) (1992) 39. HITnRUN, Phase Two (2015) P 28:11 15. Come (1994) IS MY SONG OF 16. The Black Album (1994) THE MOMENT: 17. The Gold Experience (1995) “DEAR MR. MAN” 18. Chaos and Disorder (1996) 19. Emancipation (1996) 20. Crystal Ball (1998) 21. The Truth (1998) 22. The Vault: Old Friends 4 Sale (1999) 23. Rave Un2 the Joy Fantastic (1999) DONATE TO MUSIC EDUCATION #HonorPRN PRINCE JUNE 7, 1958 — THIRD THURSDAY IN APRIL THE ULTIMATE LISTENING-RETROSPECT 051916-031617 1 1 FOR YOU You’re breakin’ my heart and takin’ me away 1 For You 2. In Love (In love) April 7, 1978 Ever since I met you, baby I’m fallin’ baby, girl, what can I do? I’ve been wantin’ to lay you down I just can’t be without you But it’s so hard to get ytou Baby, when you never come I’m fallin’ in love around I’m fallin’ baby, deeper everyday Every day that you keep it away (In love) It only makes me want it more You’re breakin’ my heart and takin’ Ooh baby, just say the word me away And I’ll be at your door (In love) And I’m fallin’ baby. -

Prince Talks and with the Release of 'Graffiti Bridge,' the Soundtrack to His Forthcoming Movie Musical, the Critics Are Listening

Prince Talks And with the release of 'Graffiti Bridge,' the soundtrack to his forthcoming movie musical, the critics are listening. But don't even try to take notes. Prince performing at Wembley, London, August 22nd, 1990. Graham Wiltshire/Hulton Archive/Getty By Neal Karlen October 18, 1990 The phone rings at 4:48 in the morning. "Hi, it's Prince," says the wide-awake voice calling from a room several yards down the hallway of this London hotel. "Did I wake you up?" Though it's assumed that Prince does in fact sleep, no one on his summer European Nude Tour can pinpoint precisely when. Prince seems to relish the aura of night stalker; his vampire hours have been a part of his mad-genius myth ever since he was waging junior-high-school band battles on Minneapolis's mostly black North Side. "Anyone who was around back then knew what was happening," Prince had said two days earlier, reminiscing. "I was working. When they were sleeping, I was jamming. When they woke up, I had another groove. I'm as insane that way now as I was back then." For proof, he'd produced a crinkled dime-store notebook that he carries with him like Linus's blanket. Empty when his tour started in May, the book is nearly full, with twenty-one new songs scripted in perfect grammar-school penmanship. He has also been laboring on the road over his movie musical Graffiti Bridge, which was supposed to be out this past summer and is now set for release in November. -

Music Censorship and the American Culture Wars

Parental Advisory, Explicit Content: Music Censorship and the American Culture Wars Gavin Ratcliffe Candidate for Senior Honors in History Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Clayton Koppes Spring Semester 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgments…………………………………………………………….…………….Page II Introduction……………………………………………………………………………….....Page 1 Chapter 1: Censorship and Morality……………………………………………………… Page 10 Chapter 2: Rockin’ and Rollin’ with the PMRC…………………………………………...Page 20 Chapter 3: Killing the Dead Kennedys…………………………………………………….Page 31 Chapter 4: As Legally Nasty as they Wanna Be…………………………………...............Page 40 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………….Page 60 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………..…Page 63 Ratcliffe I Acknowledgements To my grandmother, Jennifer Roff, for 22 years, and counting, of love and support Ratcliffe II Introduction In December, 1984 Tipper Gore bought her 11 year old daughter, Karenna, Prince’s Purple Rain album. Like many other young children, Karenna had heard Prince’s music on the radio and wanted to hear more. Upon listening to the full album Karenna alerted her mother to the provocative nature of some of Prince’s lyrics, such as the track “Darling Nikki,” which contained the lyrics “I knew a girl named Nikki/Guess you could say she was a sex fiend/I met her in a hotel lobby/Masturbating with a magazine.”1 Tipper and Karenna Gore were embarrassed and ashamed that they were listening to such vulgar music, that they were doing so in their home. Deviance and profanity, something that one would expect to find in the street or back alleys had gotten into their home, albeit unwittingly. Tipper Gore soon realized that similar content was being broadcast into their home through other mediums, such as the new, wildly popular Music Television (MTV). -

Two Conceptions of Consciousness and Why Only the Neo-Aristotelian One Enables Us to Construct Evolutionary Explanations ✉ Harry Smit1 & Peter Hacker2

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00591-y OPEN Two conceptions of consciousness and why only the neo-Aristotelian one enables us to construct evolutionary explanations ✉ Harry Smit1 & Peter Hacker2 Descartes separated the physical from the mental realm and presupposed a causal relation between conscious experience and neural processes. He denominated conscious experiences 1234567890():,; ‘thoughts’ and held them to be indubitable. However, the question of how we can bridge the gap between subjective experience and neural activity remained unanswered, and attempts to integrate the Cartesian conception with evolutionary theory has not resulted in explana- tions and testable hypotheses. It is argued that the alternative neo-Aristotelian conception of the mind as the capacities of intellect and will resolves these problems. We discuss how the neo-Aristotelian conception, extended with the notion that organisms are open thermo- dynamic systems that have acquired heredity, can be integrated with evolutionary theory, and elaborate how we can explain four different forms of consciousness in evolutionary terms. 1 Department of Cognitive Neuroscience, Faculty of Psychology and Neuroscience, Maastricht University, P.O. Box 6166200 MD Maastricht, ✉ The Netherlands. 2 St John’s College, Oxford OX1 3JP, UK. email: [email protected] HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | (2020) 7:93 | https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00591-y 1 ARTICLE HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00591-y Introduction his paper discusses essentials differences between two entity that has changed, is dirty, or has been turned. We then Tconceptions of mind, namely the Cartesian and neo- speak of a human being (not of a mind) of whom we say different Aristotelian conception. -

Pop Stars and Idolatry: an Investigation of the Worship of Popular Music Icons, and the Music and Cult of Prince R. Till

University of Huddersfield Repository Till, Rupert Pop stars and idolatry: an investigation of the worship of popular music icons, and the music and cult of Prince. Original Citation Till, Rupert (2010) Pop stars and idolatry: an investigation of the worship of popular music icons, and the music and cult of Prince. Journal of Beliefs and Values: Studies in Religion and Education, 31 (1). pp. 69-80. ISSN 1361-7672 This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/13251/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Pop stars and idolatry: an investigation of the worship of popular music icons, and the music and cult of Prince R. Till Department of Music and Drama, University of Huddersfield, Huddersfield, England Email: [email protected] Abstract: Prince is an artist who integrates elements from the sacred into his work.