Explore Music 7–9: Appendices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bach Experience

MUSIC AT MARSH CHAPEL 10|11 Scott Allen Jarrett Music Director Sunday, December 12, 2010 – 9:45A.M. The Bach Experience BWV 62: ‘Nunn komm, der Heiden Heiland’ Marsh Chapel Choir and Collegium Scott Allen Jarrett, DMA, presenting General Information - Composed in Leipzig in 1724 for the first Sunday in Advent - Scored for two oboes, horn, continuo and strings; solos for soprano, alto, tenor and bass - Though celebratory as the musical start of the church year, the cantata balances the joyful anticipation of Christ’s coming with reflective gravity as depicted in Luther’s chorale - The text is based wholly on Luther’s 1524 chorale, ‘Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland.’ While the outer movements are taken directly from Luther, movements 2-5 are adaptations of the verses two through seven by an unknown librettist. - Duration: about 22 minutes Some helpful German words to know . Heiden heathen (nations) Heiland savior bewundert marvel höchste highest Beherrscher ruler Keuschheit purity nicht beflekket unblemished laufen to run streite struggle Schwachen the weak See the morning’s bulletin for a complete translation of Cantata 62. Some helpful music terms to know . Continuo – generally used in Baroque music to indicate the group of instruments who play the bass line, and thereby, establish harmony; usually includes the keyboard instrument (organ or harpsichord), and a combination of cello and bass, and sometimes bassoon. Da capo – literally means ‘from the head’ in Italian; in musical application this means to return to the beginning of the music. As a form (i.e. ‘da capo’ aria), it refers to a style in which a middle section, usually in a different tonal area or key, is followed by an restatement of the opening section: ABA. -

Dynamic Generation of Musical Notation from Musicxml Input on an Android Tablet

Dynamic Generation of Musical Notation from MusicXML Input on an Android Tablet THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Laura Lynn Housley Graduate Program in Computer Science and Engineering The Ohio State University 2012 Master's Examination Committee: Rajiv Ramnath, Advisor Jayashree Ramanathan Copyright by Laura Lynn Housley 2012 Abstract For the purpose of increasing accessibility and customizability of sheet music, an application on an Android tablet was designed that generates and displays sheet music from a MusicXML input file. Generating sheet music on a tablet device from a MusicXML file poses many interesting challenges. When a user is allowed to set the size and colors of an image, the image must be redrawn with every change. Instead of zooming in and out on an already existing image, the positions of the various musical symbols must be recalculated to fit the new dimensions. These changes must preserve the relationships between the various musical symbols. Other topics include the laying out and measuring of notes, accidentals, beams, slurs, and staffs. In addition to drawing a large bitmap, an application that effectively presents sheet music must provide a way to scroll this music across a small tablet screen at a specified tempo. A method for using animation on Android is discussed that accomplishes this scrolling requirement. Also a generalized method for writing text-based documents to describe notations similar to musical notation is discussed. This method is based off of the knowledge gained from using MusicXML. -

Kisd Band Ms 3 Curriculum Year at a Glance

KISD BAND MS 3 CURRICULUM YEAR AT A GLANCE TEXT: Essential Elements for Band THE LEARNER WILL: 1st 9-Weeks 2nd 9-Weeks 3rd 9-Weeks 4th 9-Weeks Identify, define, write, and analyze whole, half, quarter, paired and single Identify, define, write, and analyze all previously learned elements adding eighth, sixteenth, dotted half, and dotted quarter notes with corresponding 9/8, 12/8, and 5/4 time signatures and the keys of G and Db. (1B, 1D, 1C, rests in simple time and dotted quarters and triplets in compound time; 2B, 3F) multi-measure rests; repeat, first and second endings, da capo al fine, dal segno al fine, da capo al coda, dal segno al coda; dynamics (pp-ff); staccato, Identify, define, write and analyze all previously learned elements in addition to the following: largo-presto, sforzando, fortepiano, chord structures legato, accent, marcato; crescendo, decrescendo; 2/4, 3/4 ,4/4, 2/2, 6/8; keys and tuning in a major key. (1B, 1D, 1C, 2B, 3F) of Bb, Eb, F; instrument names; musical forms; fermata; andante, moderato, ritardando, accelerando, largo, adagio, allegro. (1B, 1D, 1C, 2B, 3F) Perform a 2 octave chromatic scale with correct pitch, fingerings, and Perform from memory a 2 octave chromatic scale with correct pitch, Perform from memory a 2 octave chromatic scale with correct pitch, Perform from memory a 2 octave chromatic scale with correct pitch, accurate intonation. (1B) fingerings, and accurate intonation (quarter = 80bpm utilizing an eighth fingerings and accurate intonation (quarter = 100bpm utilizing an eighth fingerings, and accurate intonation (quarter = 100bpm utilizing a triplet note pattern). -

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED

TIME SIGNATURES, TEMPO, BEAT and GORDONIAN SYLLABLES EXPLAINED TIME SIGNATURES Time Signatures are represented by a fraction. The top number tells the performer how many beats in each measure. This number can be any number from 1 to infinity. However, time signatures, for us, will rarely have a top number larger than 7. The bottom number can only be the numbers 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, et c. These numbers represent the note values of a whole note, half note, quarter note, eighth note, sixteenth note, thirty- second note, sixty-fourth note, one hundred twenty-eighth note, two hundred fifty-sixth note, five hundred twelfth note, et c. However, time signatures, for us, will only have a bottom numbers 2, 4, 8, 16, and possibly 32. Examples of Time Signatures: TEMPO Tempo is the speed at which the beats happen. The tempo can remain steady from the first beat to the last beat of a piece of music or it can speed up or slow down within a section, a phrase, or a measure of music. Performers need to watch the conductor for any changes in the tempo. Tempo is the Italian word for “time.” Below are terms that refer to the tempo and metronome settings for each term. BPM is short for Beats Per Minute. This number is what one would set the metronome. Please note that these numbers are generalities and should never be considered as strict ranges. Time Signatures, music genres, instrumentations, and a host of other considerations may make a tempo of Grave a little faster or slower than as listed below. -

The Baroque. 3.3: Vocal Music: the Da Capo Aria and Other Types of Arias

UNIT 3: THE BAROQUE. 3.3: VOCAL MUSIC: THE DA CAPO ARIA AND OTHER TYPES OF ARIAS EXPLANATION 3.3: THE DA CAPO ARIA AND OTHER TYPES OF ARIAS. THE ARIA The aria in the operas is the part sung by the soloist. It is opposed to the recitative, which uses the recitative style. In the arias the composer shows and exploits the dramatic and emotional situations, it becomes the equivalent of a soliloquy (one person speach) in the spoken plays. In the arias, the interpreters showed their technique, they showed off, even in excess, which provoked a lot of criticism from poets and musicians. They were often sung by castrati: soprano men undergoing a surgical operation so as not to change their voice when they grew up. One of them, the most famous, Farinelli, acquired international fame for his great technique and vocal expression. He lived twenty-five years in Spain. THE DA CAPO ARIA The Da Capo aria is a vocal work in three parts or sections (tripartite form). It began to be used in the Baroque in operas, oratorios and cantatas. The form is A - B - A, the last part being a repetition of the first. 1. The first section is a complete musical entity, that is to say, it could be sung alone and musically it would have complete meaning since it ends in the tonic. The tonic is the first grade or note of a scale. 2. The second section contrasts with the first section in tonality, texture, mood and sometimes in tempo (speed). 3. -

Chapter 1 "The Elements of Rhythm: Sound, Symbol, and Time"

This is “The Elements of Rhythm: Sound, Symbol, and Time”, chapter 1 from the book Music Theory (index.html) (v. 1.0). This book is licensed under a Creative Commons by-nc-sa 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/ 3.0/) license. See the license for more details, but that basically means you can share this book as long as you credit the author (but see below), don't make money from it, and do make it available to everyone else under the same terms. This content was accessible as of December 29, 2012, and it was downloaded then by Andy Schmitz (http://lardbucket.org) in an effort to preserve the availability of this book. Normally, the author and publisher would be credited here. However, the publisher has asked for the customary Creative Commons attribution to the original publisher, authors, title, and book URI to be removed. Additionally, per the publisher's request, their name has been removed in some passages. More information is available on this project's attribution page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/attribution.html?utm_source=header). For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page (http://2012books.lardbucket.org/). You can browse or download additional books there. i Chapter 1 The Elements of Rhythm: Sound, Symbol, and Time Introduction The first musical stimulus anyone reacts to is rhythm. Initially, we perceive how music is organized in time, and how musical elements are organized rhythmically in relation to each other. Early Western music, centering upon the chant traditions for liturgical use, was arhythmic to a great extent: the flow of the Latin text was the principal determinant as to how the melody progressed through time. -

SCOPE and SEQUENCE for Instrumental Music Program

Poway Unified School District Instrumental Music Scope and Sequence – Grades 5 through 12 The mission of the Poway Unified School District Instrumental Music Program is to provide a quality music education for students. Through the development of rhythmic, melodic, and expressive senses, utilizing a variety of musical repertoire and technology, students will work together to achieve common goals to: • Improve the individual musical performance and ensemble skills of its members • Strengthen an awareness of the value and tradition of music in our individual and collective lives • Develop strong leaders, who will become productive, resilient and innovative members of society • Reinforce long term ensemble participation as a tool for college readiness • Reinforce learning through explicit teaching for transfer across the curriculum GRADE RHYTHMIC SENSE MELODIC SENSE EXPRESSIVE SENSE Understanding rhythms, beats groupings, Understanding notes, pitch, and sound in Understanding expressive qualities that and time signatures for artistic purpose relation to artistic expression transform music into artistic experiences 5 Notes – quarter, half, dotted half, whole, • Introduction to note reading (knowing • Dynamics – piano, mezzo piano, mezzo paired eighth note names and fingering/position) forte, forte, crescendo, decrescendo Rests – quarter, half, whole, multiple • Major key signatures and scales (one • Tempo – Andante, Adagio, Moderato, measure rest octave, two octave within reason) Allegro, fermata Time Signature – 4/4 (Common Time), 3/4, - -

Composers' Bridge!

Composers’ Bridge Workbook Contents Notation Orchestration Graphic notation 4 Orchestral families 43 My graphic notation 8 Winds 45 Clefs 9 Brass 50 Percussion 53 Note lengths Strings 54 Musical equations 10 String instrument special techniques 59 Rhythm Voice: text setting 61 My rhythm 12 Voice: timbre 67 Rhythmic dictation 13 Tips for writing for voice 68 Record a rhythm and notate it 15 Ideas for instruments 70 Rhythm salad 16 Discovering instruments Rhythm fun 17 from around the world 71 Pitch Articulation and dynamics Pitch-shape game 19 Articulation 72 Name the pitches – part one 20 Dynamics 73 Name the pitches – part two 21 Score reading Accidentals Muddling through your music 74 Piano key activity 22 Accidental practice 24 Making scores and parts Enharmonics 25 The score 78 Parts 78 Intervals Common notational errors Fantasy intervals 26 and how to catch them 79 Natural half steps 27 Program notes 80 Interval number 28 Score template 82 Interval quality 29 Interval quality identification 30 Form Interval quality practice 32 Form analysis 84 Melody Rehearsal and concert My melody 33 Presenting your music in front Emotion melodies 34 of an audience 85 Listening to melodies 36 Working with performers 87 Variation and development Using the computer Things you can do with a Computer notation: Noteflight 89 musical idea 37 Sound exploration Harmony My favorite sounds 92 Harmony basics 39 Music in words and sentences 93 Ear fantasy 40 Word painting 95 Found sound improvisation 96 Counterpoint Found sound composition 97 This way and that 41 Listening journal 98 Chord game 42 Glossary 99 Welcome Dear Student and family Welcome to the Composers' Bridge! The fact that you are being given this book means that we already value you as a composer and a creative artist-in-training. -

The Development of Musical Notation Carolyn S

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville The Research and Scholarship Symposium The 2015 yS mposium Apr 1st, 2:20 PM - 2:40 PM Slashes, Dashes, Points, and Squares: The Development of Musical Notation Carolyn S. Gorog Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ research_scholarship_symposium Part of the Composition Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Gorog, Carolyn S., "Slashes, Dashes, Points, and Squares: The eD velopment of Musical Notation" (2015). The Research and Scholarship Symposium. 5. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/research_scholarship_symposium/2015/podium_presentations/5 This Podium Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Research and Scholarship Symposium by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Slashes, Dashes, Points, and Squares: The development of Musical Notation Slashes, Dashes, Points, and Squares: The Development of Musical Notation Music has been around for a long time; in almost every culture around the world we find evidence of music. Music throughout history started as mostly vocal music, it was transmitted orally with no written notation. During the early ninth and tenth century the written tradition started to be seen and developed. This marked the beginnings of music notation. Music notation has gone through many stages of development from neumes, square notes, and four-line staff, to modern notation. Although modern notation works very well, it is not necessarily superior to methods used in the Renaissance and Medieval periods. In Western music neumes are the name given to the first type of notation used. -

From Neumes to Notation: a Thousand Years of Passing on the Music by Charric Van Der Vliet

From Neumes to Notation: A Thousand Years of Passing On the Music by Charric Van der Vliet Classical musicians, in the terminology of the 17th and 18th century musical historians, like to sneer at earlier music as "primitive", "rough", or "uncouth". The fact of the matter is that during the thousand years from 450 AD to about 1450 AD, Western Civilization went from no recording of music at all to a fully formed method of passing on the most intricate polyphony. That is no small achievement. It's attractive, I suppose, to assume the unthinking and barbaric nature of our ancestors, since it implies a certain smugness about "how far we've come." I've always thought that painting your ancestors as stupid was insulting both to them and to yourself. The barest outline of a thousand year journey only hints at the difficulties our medieval ancestors had to face to be musical. This is an attempt at sketching that outline. Each of the sub-headings of this lecture contains material for lifetimes of musical study. It is hoped that outlining this territory may help shape where your own interests will ultimately lie. Neumes: In the beginning, choristers needed reminders as to which way notes went. "That fifth note goes DOWN, George!" This situation was remedied by noting when the movement happened and what direction, above the text, with wavy lines. "Neume" was the adopted term for this. It's a Middle English corruption of the Greek word for breath, "pneuma." Then, to specify note's exact pitch was the next innovation. -

Music Braille Code, 2015

MUSIC BRAILLE CODE, 2015 Developed Under the Sponsorship of the BRAILLE AUTHORITY OF NORTH AMERICA Published by The Braille Authority of North America ©2016 by the Braille Authority of North America All rights reserved. This material may be duplicated but not altered or sold. ISBN: 978-0-9859473-6-1 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-9859473-7-8 (Braille) Printed by the American Printing House for the Blind. Copies may be purchased from: American Printing House for the Blind 1839 Frankfort Avenue Louisville, Kentucky 40206-3148 502-895-2405 • 800-223-1839 www.aph.org [email protected] Catalog Number: 7-09651-01 The mission and purpose of The Braille Authority of North America are to assure literacy for tactile readers through the standardization of braille and/or tactile graphics. BANA promotes and facilitates the use, teaching, and production of braille. It publishes rules, interprets, and renders opinions pertaining to braille in all existing codes. It deals with codes now in existence or to be developed in the future, in collaboration with other countries using English braille. In exercising its function and authority, BANA considers the effects of its decisions on other existing braille codes and formats, the ease of production by various methods, and acceptability to readers. For more information and resources, visit www.brailleauthority.org. ii BANA Music Technical Committee, 2015 Lawrence R. Smith, Chairman Karin Auckenthaler Gilbert Busch Karen Gearreald Dan Geminder Beverly McKenney Harvey Miller Tom Ridgeway Other Contributors Christina Davidson, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Richard Taesch, BANA Music Technical Committee Consultant Roger Firman, International Consultant Ruth Rozen, BANA Board Liaison iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................. -

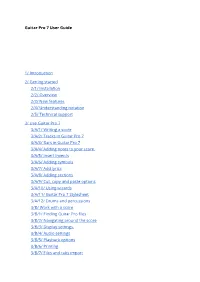

Guitar Pro 7 User Guide 1/ Introduction 2/ Getting Started

Guitar Pro 7 User Guide 1/ Introduction 2/ Getting started 2/1/ Installation 2/2/ Overview 2/3/ New features 2/4/ Understanding notation 2/5/ Technical support 3/ Use Guitar Pro 7 3/A/1/ Writing a score 3/A/2/ Tracks in Guitar Pro 7 3/A/3/ Bars in Guitar Pro 7 3/A/4/ Adding notes to your score. 3/A/5/ Insert invents 3/A/6/ Adding symbols 3/A/7/ Add lyrics 3/A/8/ Adding sections 3/A/9/ Cut, copy and paste options 3/A/10/ Using wizards 3/A/11/ Guitar Pro 7 Stylesheet 3/A/12/ Drums and percussions 3/B/ Work with a score 3/B/1/ Finding Guitar Pro files 3/B/2/ Navigating around the score 3/B/3/ Display settings. 3/B/4/ Audio settings 3/B/5/ Playback options 3/B/6/ Printing 3/B/7/ Files and tabs import 4/ Tools 4/1/ Chord diagrams 4/2/ Scales 4/3/ Virtual instruments 4/4/ Polyphonic tuner 4/5/ Metronome 4/6/ MIDI capture 4/7/ Line In 4/8 File protection 5/ mySongBook 1/ Introduction Welcome! You just purchased Guitar Pro 7, congratulations and welcome to the Guitar Pro family! Guitar Pro is back with its best version yet. Faster, stronger and modernised, Guitar Pro 7 offers you many new features. Whether you are a longtime Guitar Pro user or a new user you will find all the necessary information in this user guide to make the best out of Guitar Pro 7. 2/ Getting started 2/1/ Installation 2/1/1 MINIMUM SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS macOS X 10.10 / Windows 7 (32 or 64-Bit) Dual-core CPU with 4 GB RAM 2 GB of free HD space 960x720 display OS-compatible audio hardware DVD-ROM drive or internet connection required to download the software 2/1/2/ Installation on Windows Installation from the Guitar Pro website: You can easily download Guitar Pro 7 from our website via this link: https://www.guitar-pro.com/en/index.php?pg=download Once the trial version downloaded, upgrade it to the full version by entering your licence number into your activation window.