Sustainable Building Legislation and Incentives in Korea: a Case-Study-Based Comparison of Building New and Renovation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D2492609215cd311123628ab69

Acknowledgements Publisher AN Cheongsook, Chairperson of KOFIC 206-46, Cheongnyangni-dong, Dongdaemun-gu. Seoul, Korea (130-010) Editor in Chief Daniel D. H. PARK, Director of International Promotion Department Editors KIM YeonSoo, Hyun-chang JUNG English Translators KIM YeonSoo, Darcy PAQUET Collaborators HUH Kyoung, KANG Byeong-woon, Darcy PAQUET Contributing Writer MOON Seok Cover and Book Design Design KongKam Film image and still photographs are provided by directors, producers, production & sales companies, JIFF (Jeonju International Film Festival), GIFF (Gwangju International Film Festival) and KIFV (The Association of Korean Independent Film & Video). Korean Film Council (KOFIC), December 2005 Korean Cinema 2005 Contents Foreword 04 A Review of Korean Cinema in 2005 06 Korean Film Council 12 Feature Films 20 Fiction 22 Animation 218 Documentary 224 Feature / Middle Length 226 Short 248 Short Films 258 Fiction 260 Animation 320 Films in Production 356 Appendix 386 Statistics 388 Index of 2005 Films 402 Addresses 412 Foreword The year 2005 saw the continued solid and sound prosperity of Korean films, both in terms of the domestic and international arenas, as well as industrial and artistic aspects. As of November, the market share for Korean films in the domestic market stood at 55 percent, which indicates that the yearly market share of Korean films will be over 50 percent for the third year in a row. In the international arena as well, Korean films were invited to major international film festivals including Cannes, Berlin, Venice, Locarno, and San Sebastian and received a warm reception from critics and audiences. It is often said that the current prosperity of Korean cinema is due to the strong commitment and policies introduced by the KIM Dae-joong government in 1999 to promote Korean films. -

The Republic of Korea

The impact of COVID-19 on older persons in the Republic of Korea Samsik Lee Ae Son Om Sung Min Kim Nanum Lee Institute of Aging Society, Hanyang University Seoul, Republic of Korea The impact of COVID-19 on older persons in the Republic of Korea This report is prepared with the cooperation of HelpAge International. To cite this report: Samsik Lee, Ae Son Om, Sung Min Kim, Nanum Lee (2020), The impact of COVID-19 on older persons in in the Republic of Korea, HelpAge International and Institute of Aging Society, Hanyang University, Seoul, ISBN: 979-11-973261-0-3 Contents Chapter 1 Context 01 1. COVID -19 situation and trends 1.1. Outbreak of COVID-19 1.2. Ruling on social distancing 1.3. Three waves of COVID-19 09 2. Economic trends 2.1. Gloomy economic outlook 2.2. Uncertain labour market 2.3. Deepening income equality 13 3. Social trends 3.1. ICT-based quarantine 3.2. Electronic entry 3.3. Non-contact socialization Chapter 2 Situation of older persons Chapter 3 Responses 16 1. Health and care 47 1. Response from government 1.1. COVID-19 among older persons 1.1. Key governmental structures Higher infection rate for the young, higher death rate for the elderly 1.2. COVID-19 health and safety Critical elderly patients out of hospital Total inspections Infection routes among the elderly Cohort isolation 1.2. Healthcare system and services 1.3. Programming and services Threat to primary health system Customized care services for senior citizens Socially distanced welfare facilities for elderly people Senior Citizens' Job Project Emergency care services Online exercise 1.3. -

Heerim a Rchitects & Planners

Heerim Architects & Planners & Planners Heerim Architects Your Global Design Partner Selected Projects Heerim Architects & Planners Co., Ltd. Seoul, Korea Baku, Azerbaijan Beijing, China Doha, Qatar Dhaka, Bangladesh Dubai, UAE Erbil, Iraq Hanoi, Vietnam Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam New York, USA Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan Phnom Penh, Cambodia Tashkent, Uzbekistan www.heerim.com 1911 We Design Tomorrow & Beyond 1 CEO Message Heerim, always in the pursuit of a client’s interest and satisfaction Founded in 1970, Heerim Architects & Planners is the leading architectural practice of Korea successfully expanding its mark in both domestic and international markets. Combined with creative thinking, innovative technical knowledge and talented pool of professionals across all disciplines, Heerim provides global standard design solutions in every aspect of the project. Our services strive to exceed beyond the client expectations which extend from architecture, construction management to one-stop Design & Build Management Services delivering a full solution package. Under the vision of becoming the leading Corporate Profile History global design provider, Heerim continues to challenge our goals firmly rooted in our corporate philosophy that “growth Name Heerim Architects & Planners Co., Ltd. 1970 Founded as Heerim Architects & Planners of the company is meaningful when it contributes to a happy, Address 39, Sangil-ro 6-gil, Gangdong-gu, Seoul 05288, Korea 1996 Established In-house Research Institute CEO Jeong, Young Kyoon 1997 Acquired ISO 9001 Certification fulfilled life for all”. Combined with dedicated and innovative 2000 Listed in KOSDAQ CEO / Chair of the Board Jeong, Young Kyoon President Lee, Mog Woon design minds, Heerim continues to expand, diversify, and Licensed and Registered for International Construction Business AIA, KIRA Heo, Cheol Ho 2004 Acquired ISO 14001 Certification explore worldwide where inspiring opportunities allure us. -

Hymenoptera: Symphyta: Argidae) from South Korea with Key to Species of the Subfamily Arginae

Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity 9 (2016) 183e193 HOSTED BY Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/japb Original article Three new species of the genus Arge (Hymenoptera: Symphyta: Argidae) from South Korea with key to species of the subfamily Arginae Jin-Kyung Choi a, Su-Bin Lee a, Meicai Wei b, Jong-Wook Lee a,* a Department of Life Sciences, Yeungnam University, Gyeongsan, South Korea b Key Laboratory of Cultivation and Protection for Non-Wood Forest Trees (Central South University of Forestry and Technology), Ministry of Education, Changsha, China article info abstract Article history: Three new species, Arge koreana Wei & Lee sp. nov. from South Korea, Arge pseudorejecta Wei & Lee sp. Received 20 January 2016 nov., and Arge shengi Wei & Lee sp. nov. from South Korea and China are described. Keys to known genera Received in revised form of Argidae and known species of Arginae from South Korea are provided. 11 February 2016 Copyright Ó 2016, National Science Museum of Korea (NSMK) and Korea National Arboretum (KNA). Accepted 15 February 2016 Production and hosting by Elsevier. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http:// Available online 24 February 2016 creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Keywords: Arginae China key Korea Introduction Takeuchi 1927, 1939; Doi 1938; Kim 1957, 1963, 1970; Togashi 1973, 1990, 1997; Zombori 1974, 1978; Paek et al 2010; Shinohara Taeger et al (2010) listed 58 genera and 913 valid species and et al 2009; Shinohara et al 2012). -

TEFL Contactscontacts Usefuluseful Informationinformation Andand Contactscontacts

TEFLTEFL ContactsContacts UsefulUseful informationinformation andand contactscontacts www.onlinetefl.comwww.onlinetefl.com 1000’s of job contacts – designed to help you find the job of your dreams You’ve done all the hard work, you’ve completed a TEFL course, you’ve studied for hours and now you’ll have to spend weeks trawling through 100’s of websites and job’s pages trying to find a decent job! But do not fear, dear reader, there is help at hand! We may have mentioned it before, but we’ve been doing this for years, so we’ve got thousands of job contacts around the world and one or two ideas on how you can get a decent teaching job overseas - without any of the hassle. Volunteer Teaching Placements Working as a volunteer teacher gives you much needed experience and will be a fantastic addition to your CV. We have placements in over 20 countries worldwide and your time and effort will make a real difference to the lives of your students. Paid Teaching Placements We’ll find you well-paid work in language schools across the world, we’ll even arrange accommodation and an end of contract bonus. Get in touch and let us do all the hard work for you. For more information, give us a call on: +44 (0)870 333 2332 –UK (Toll free) 1 800 985 4864 – USA +353 (0)58 40050 – Republic of Ireland +61 1300 556 997 – Australia Or visit www.i-to-i.com If you’re determined to find your own path, then our list of 1000’s of job contacts will give you all the information you’ll need to find the right job in the right location. -

Age-Friendly

AGE-FRIENDLY Lessons CITIESfrom Seoul and Singapore AGE-FRIENDLY LessonsCITIES from Seoul and Singapore For product information, please contact Project Team CLC Publications +65 66459576 Seoul Centre for Liveable Cities The Seoul Institute 45 Maxwell Road #07-01 Project Co-lead: Dr. Hyun-Chan Ahn, Associate Research Fellow The URA Centre Researchers: Dr. Chang Yi, Research Fellow Singapore 069118 Dr. Min-Suk Yoon, Research Fellow [email protected] Seoul Welfare Foundation Cover photo Researchers: Dr. Eunha Jeong, Senior Principal Researcher Seoul – Courtesy of Seoul Institute (top) Singapore – Courtesy of Ministry of Health, Singapore (bottom) Singapore Centre for Liveable Cities Project Co-lead: Elaine Tan, Deputy Director Researchers: Deborah Chan, Manager Tan Guan Hong, Manager Contributing Staff: Remy Guo, Senior Assistant Director Editor: Alvin Pang Supporting Agencies: Housing & Development Board Li Ping Goh, Director Yushan Teo, Deputy Director Tian Hong Liow, Principal Architect Yvonne KH Yee, Principal Estate Manager Printed on Tauro, a FSC-certified paper. Ministry of Health Sharon Chua, Assistant Director E-book ISBN 978-981-11-9306-4 Daniel Chander, Assistant Manager Paperback ISBN 978-981-11-9304-0 People’s Association All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or Adam Tan, Assistant Director transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of Urban Redevelopment Authority the publisher. Agnes Won, Executive Planner Juliana Tang, Executive Planner Every effort has been made to trace all sources and copyright holders of news articles, figures and information in this book before publication. -

A Study of Perceptions of How to Organize Local Government Multi-Lateral Cross- Boundary Collaboration

Title Page A Study of Perceptions of How to Organize Local Government Multi-Lateral Cross- Boundary Collaboration by Min Han Kim B.A. in Economics, Korea University, 2010 Master of Public Administration, Seoul National University, 2014 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2021 Committee Membership Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH GRADUATE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS This dissertation was presented by Min Han Kim It was defended on February 2, 2021 and approved by George W. Dougherty, Jr., Assistant Professor, Graduate School of Public and International Affairs William N. Dunn, Professor, Graduate School of Public and International Affairs Tobin Im, Professor, Graduate School of Public Administration, Seoul National University Dissertation Advisor: B. Guy Peters, Maurice Falk Professor of American Government, Department of Political Science ii Copyright © by Min Han Kim 2021 iii Abstract A Study of Perceptions of How to Organize Local Government Multi-Lateral Cross- Boundary Collaboration Min Han Kim University of Pittsburgh, 2021 This dissertation research is a study of subjectivity. That is, the purpose of this dissertation research is to better understand how South Korean local government officials perceive the current practice, future prospects, and potential avenues for development of multi-lateral cross-boundary collaboration among the governments that they work for. To this purpose, I first conduct literature review on cross-boundary intergovernmental organizations, both in the United States and in other countries. Then, I conduct literature review on regional intergovernmental organizations (RIGOs). -

Introduction to One-Stop Services for Pregnancy and Childbirth

Introduction to One-Stop Services for Pregnancy and Childbirth Ⅰ Background ○ Many people had little information about public services related to pregnancy and childbirth and found it inconvenient to prepare supporting documents for every service they apply for and visit several agencies* to apply for different services. * Health centers and employment centers in cities and smaller districts, National Health Insurance Service, National Pension Service, financial institutions, etc. ○ To address this, the government decided to find out pregnancy and childbirth related services that can be provided in one place and proactively before any needs arise, and adopt a simpler application process. ※ (One-Stop) People had to check and apply for each service, but now the government informs people of the services they need in advance; people had to visit multiple agencies, but now they can apply for all services in one place; and people had to complete every application form for each service, but now all they need is to complete a single integrated application form. ⇨ The government integrated all of the services found more effective when provided together into a system called One-Stop Services for Pregnancy and Childbirth and started to provide customized services for different needs. - 1 - Ⅱ Developments ○ In its new year work report for 2015, the government announced its plan to “realize customized services for public needs” (Jan 21, 2015). ※ The government plan aimed at proactively providing customized services for people’s life stages, such as pregnancy, childbirth, employment and death ○ Based on the results of surveys and analyses of pregnancy and childbirth support services, the government started to develop a new program (May 2015 - ). -

Strategic Planning Indicators for Urban Regeneration: a Case Study on Mixed-Use Development in Seoul

19TH ANNUAL PACIFIC-RIM REAL ESTATE SOCIETY CONFERENCE MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA, 13-16 JANUARY 2013 STRATEGIC PLANNING INDICATORS FOR URBAN REGENERATION: A CASE STUDY ON MIXED-USE DEVELOPMENT IN SEOUL JU HYUN LEE, MICHAEL Y. MAK AND WILLIAM D. SHER School of Architecture and Built Environment University of Newcastle ABSTRACT Following rapid economic growth, older sections of Seoul have experienced a decline. Mixed-used Developments (MXDs) offer viable approaches for urban regeneration in Seoul. The MXD projects that have been constructed were intended to improve built environments as well as revitalise social and local culture. Whilst visions and directions for urban regeneration in world cites are well documented, little is understood of the strategic planning of urban projects in Seoul. This paper investigates five MXD projects via 12 strategic planning factors. It outlines the opportunities and challenges of MXD projects within Seoul contexts. The factors consisted of 41 strategic planning schemes, extracted from relevant literature and a survey of experts. We used 30 strategic planning schemes as indicators for measuring strategic planning to support urban regeneration. The results of a case study indicate that strategic planning for ‘User convenience’, ‘Functional integration’ and ‘Visual perception’ is commonly applied to five projects. However, strategic approaches to ‘Divergence of connection’, ‘Regional identity’, ‘Art & design unification’ and ‘Amenity of low levels’ vary with different visions and urban functions. This implies that the underlying strategic planning of MXD projects can be characterised via our strategic planning indicators. The case study has allowed us to explore MXD projects and the strategic planning indicators for urban regeneration with an understanding of the urban context of the city. -

List of Districts of South Korea

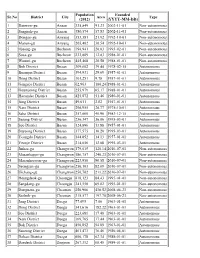

Population Founded Sr.No District City Area Type (2012) (YYYY-MM-DD) 1 Danwon-gu Ansan 335,849 91.23 2002-11-01 Non-autonomous 2 Sangnok-gu Ansan 380,574 57.83 2002-11-01 Non-autonomous 3 Dongan-gu Anyang 353,381 21.92 1992-10-01 Non-autonomous 4 Manan-gu Anyang 265,462 36.54 1992-10-01 Non-autonomous 5 Ojeong-gu Bucheon 194,941 20.03 1993-02-01 Non-autonomous 6 Sosa-gu Bucheon 232,809 12.83 1988-01-01 Non-autonomous 7 Wonmi-gu Bucheon 445,468 20.58 1988-01-01 Non-autonomous 8 Buk District Busan 309,602 39.44 1978-02-15 Autonomous 9 Busanjin District Busan 394,931 29.69 1957-01-01 Autonomous 10 Dong District Busan 101,251 9.78 1957-01-01 Autonomous 11 Gangseo District Busan 62,963 180.24 1988-01-01 Autonomous 12 Geumjeong District Busan 255,979 65.17 1988-01-01 Autonomous 13 Haeundae District Busan 425,872 51.46 1980-01-01 Autonomous 14 Jung District Busan 49,011 2.82 1957-01-01 Autonomous 15 Nam District Busan 296,955 26.77 1975-10-01 Autonomous 16 Saha District Busan 357,060 40.96 1983-12-15 Autonomous 17 Sasang District Busan 256,347 36.06 1995-03-01 Autonomous 18 Seo District Busan 124,896 13.88 1957-01-01 Autonomous 19 Suyeong District Busan 177,575 10.20 1995-03-01 Autonomous 20 Yeongdo District Busan 144,852 14.13 1957-01-01 Autonomous 21 Yeonje District Busan 214,056 12.08 1995-03-01 Autonomous 22 Jinhae-gu Changwon 179,015 120.14 2010-07-01 Non-autonomous 23 Masanhappo-gu Changwon 186,757 240.23 2010-07-01 Non-autonomous 24 Masanhoewon-gu Changwon 223,956 90.58 2010-07-01 Non-autonomous 25 Seongsan-gu Changwon 250,103 82.09 2010-07-01 -

Analyzing the Success Factors of Best Practices in the Korean Social Economy

Analyzing the Success Factors of Best Practices in the Korean Social Economy 2019.11 " Analyzing the Success Factors of Best Practices in the Korean Social Economy Published on 29.11.2019 Published in KoSEA Published at 7,8F 157 Sujeong-ro, Sujeong-gu, Seongnam, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea Publisher In-sun Kim(president.KoSEA) Tel 031-697-7700 Fax 031-697-7889 Website http://www.socialenterprise.or.kr Designed by sangsangneomeo ※ Copyright(c)2019 by KoSEA. All Page contents cannot be Not for sale copied without permission. Research Institute Hanshin University R&DB Foundation Principal investigator Jongick Jang(Professor of Global Business Department, Hanshin University) Co-investigator Changho Oh(Professor of Department of Business Administration, Hanshin University) Hyun S. Shin(Professor of Division of Business Administration, Hanyang University) Research assistant Jungsoo Park(Graduate School for Soical Innovation Business, Hanshin University) Suyeon Lee(Graduate School for Soical Innovation Business, Hanshin University) Gyejin Choi(Graduate School for Soical Innovation Business, Hanshin University) Jeonghoon Kang(Graduate School of Business Administration, Hanyang University) Table of Contents Foreword 5 Ⅰ. iCOOP Consumer Cooperatives 9 iCOOP Consumer Cooperatives, Repeating Innovations through a Strong Network Organization Ⅱ. Ansung Health Welfare Social Cooperative 32 Ansung Health Welfare Social Cooperative, Realizing the Co-Production Model of Medical Services and Local Community Building Ⅲ. Social Cooperative Dounuri 51 Social Cooperative Dounuri, Creating Decent Jobs in Care Services Ⅳ. Happy Bridge Cooperative 67 Members of Happy Bridge Cooperative, Moving towards the Innovation from Wage Workers to Collaborative Worker Owners Ⅴ. BeautifulStore 84 Creating a beautiful world of sharing and recycling where everyone participates Ⅵ. Dasomi Foundation 103 Dasomi Foundation: Shifting the Paradigm of Care Services through Partnership and Innovation Ⅶ. -

Overseas Companies for Practical Work

International companies who have provided previous practical work opportunities to students Company Name Company Address City Country Company URL Work Nature Specialisation ANU Visual Sciences Group Research School of BiologyGPO Box 475 Canberra ACT 2601 Canberra Australia http://www.rsbs.anu.edu.au/ResearchGroups/VIS/ibbotson_lab/ subprof Biomedical ExxonMobil Australia 12 Riverside QuaySouthbank Vic 3006Melbourne Melbourne Australia http://www.exxonmobil.com.au/Australia-English/PA/default.aspx subprof Chemical & Materials Sitar Indian Restaurant 33 Anstey Street AlbionBrisbaneQLD 4010 Brisbane Australia http://www.sitar.com.au subprof Chemical & Materials Woodside Energy 240 St Georges TerracePerthWAAUSTRALIA Perth Australia http://www.woodside.com.au subprof Chemical & Materials City of Whittlesea Council 25 Ferres Boulevard South MorangVICMelbourne Melbourne Australia general,subprof Civil JK Civil Contracting Pty Ltd 234 Fleming Road, Hemmant, QLD 4174, Australia Queensland Australia general,subprof Civil Minemakers Ltd Level 2, 34 Colin StreetWest Perth 6005Western Australia Perth Australia http://www.minemakers.com.au/contact.php general,subprof Civil Structerre 1 Erindale RoadBalcatta, PerthWestern AustraliaAustralia Perth Australia http://www.structerre.com.au general,subprof Civil Sun Power Construction Pty Ltd 19A Valley RoadNSW 2122Australia Australia http://www.nowebsite.com general,subprof Civil The University of Melbourne Department of Civil & Environmental EngineeringUniversity of MelbourneVic 3010, Australia Victoria