Playas of Inland Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Playas of Inland Australia

Cadernos Lab. Xeolóxico de Laxe Coruña. 2010. Vol. 35, pp. 71 - 98 ISSN: 0213-4497 Playas of inland Australia BOURNE, J.A.1 and. TWIDALE, C.R.1 (1) School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Geology and Geophysics, The University of Adelaide, G.P.O. Box 498, Adelaide, South Australia 5005 Abstract Playas, mostly in the form of salinas, are characteristic of the Australian arid zone. Many are associated with lunettes in sebkha complexes or assemblages and can be attributed to the deflation of bare alluvial flats. Many playas are structurally controlled. Lake Eyre, for example, occupies a downfaulted segment of the crust, and many other playas large and small are associated with faults. Lakes Frome, Callabonna, Blanche, and Gregory each displays a linear shoreline, but also and arguably, all are located on a regional structural arc. Lake Gairdner occupies a valley probably blocked by faulting. Others may be caused by preferential weathering along fracture zones, some linear but others arcuate. Many salinas are developed in dismembered rivers channels, the position and pattern of which are structurally determined. But many owe their existence to the interaction of several of these factors. The various salts precipitated in playas constitute a significant resource, regional and local, past, present and future. Key words: playa, salina, sebkha, lunette, Australia 72 Bourne and Twidale CAD. LAB. XEOL. LAXE 35 (2010) INTRODUCTION by clastic sediments (hence ‘claypan’, even though the fill may consist mostly of sand) As LAMPLUGH (1917, p. 434) pointed but all the muds are saline and many carry a out, anyone not knowing better could be crust of salts of various compositions. -

Lake Torrens SA 2016, a Bush Blitz Survey Report

Lake Torrens South Australia 28 August–9 September 2016 Bush Blitz Species Discovery Program Lake Torrens, South Australia 28 August–9 September 2016 What is Bush Blitz? Bush Blitz is a multi-million dollar partnership between the Australian Government, BHP Billiton Sustainable Communities and Earthwatch Australia to document plants and animals in selected properties across Australia. This innovative partnership harnesses the expertise of many of Australia’s top scientists from museums, herbaria, universities, and other institutions and organisations across the country. Abbreviations ABRS Australian Biological Resources Study AD State Herbarium of South Australia ANIC Australian National Insect Collection CSIRO Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation DEWNR Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources (South Australia) DSITI Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation (Queensland) EPBC Act Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth) MEL National Herbarium of Victoria NPW Act National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 (South Australia) RBGV Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria SAM South Australian Museum Page 2 of 36 Lake Torrens, South Australia 28 August–9 September 2016 Summary In late August and early September 2016, a Bush Blitz survey was conducted in central South Australia at Lake Torrens National Park (managed by SA Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources) and five adjoining pastoral stations to the west (Andamooka, Bosworth, Pernatty, Purple Downs and Roxby Downs). The traditional owners of this country are the Kokatha people and they were involved with planning and preparation of the survey and accompanied survey teams during the expedition itself. Lake Torrens National Park and surrounding areas have an arid climate and are dominated by three land systems: Torrens (bed of Lake Torrens), Roxby (dunefields) and Arcoona (gibber plains). -

Olympic Dam Expansion

OLYMPIC DAM EXPANSION DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT 2009 APPENDIX P CULTURAL HERITAGE ISBN 978-0-9806218-0-8 (set) ISBN 978-0-9806218-4-6 (appendices) APPENDIX P CULTURAL HERITAGE APPENDIX P1 Aboriginal cultural heritage Table P1 Aboriginal Cultural Heritage reports held by BHP Billiton AUTHOR DATE TITLE Antakirinja Incorporated Undated – circa Report to Roxby Management Services by Antakirinja Incorporated on August 1985 Matters Related To Aboriginal Interests in The Project Area at Olympic Dam Anthropos Australis February 1996 The Report of an Aboriginal Ethnographic Field Survey of Proposed Works at Olympic Dam Operations, Roxby Downs, South Australia Anthropos Australis April 1996 The Report of an Aboriginal Archaeological Field Survey of Proposed Works at Olympic Dam Operations, Roxby Downs, South Australia Anthropos Australis May 1996 Final Preliminary Advice on an Archaeological Survey of Roxby Downs Town, Eastern and Southern Subdivision, for Olympic Dam Operations, Western Mining Corporation Limited, South Australia Archae-Aus Pty Ltd July 1996 The Report of an Archaeological Field Inspection of Proposed Works Areas within Olympic Dam Operations’ Mining Lease, Roxby Downs, South Australia Archae-Aus Pty Ltd October 1996 The Report of an Aboriginal Heritage Assessment of Proposed Works Areas at Olympic Dam Operations’ Mining Lease and Village Site, Roxby Downs, South Australia (Volumes 1-2) Archae-Aus Pty Ltd April 1997 A Report of the Detailed Re-Recording of Selected Archaeological Sites within the Olympic Dam Special -

Native Title Recognition for Two of the Oldest Claims in SA

Aboriginal Way Issue 58, Spring 2014 A publication of South Australian Native Title Services Kokatha Wangkangurru/Yarluyandi Native title recognition for two of the oldest claims in SA Two specially convened federal “I welcome everyone here today, to “Today is very special for Kokatha Complex land use negotiations with court hearings took place in celebrate our special day; I would like people. It will be remembered by Kokatha BHP and the State were a major part September and October this year to to recognise all the hard work that people present today and by future of the native title claim process. declare native title exists for areas has gone on over the years and to all generations as the day we were finally recognised as the Traditional Owners Mr Starkey said “Kokatha have been of Kokatha and Wangkangurru/ the people who have got us here today,” of a very culturally significant part of the working behind the scenes with Yarluyandi country. he said. Australian landscape,” he said. BHP billion and the Indigenous Land The Kokatha native title claims were Andrew Starkey, Chair of Kokatha Corporation to collectively secure Roxby determined by Chief Justice Allsop on The determination covers most of the Downs, Purple Downs and Andamooka Aboriginal Corporation said the day country between the Lake Gairdner 1 September at Andamooka Station. Station leases and to operate the stations will always be remembered as the salt lake and Lake Torrens, and includes as an ongoing pastoral business. Glen Wingfield welcomed everyone to day the Kokatha people were officially Roxby Downs and Olympic Dam in Kokatha Country. -

Hordern House Rare Books • Manuscripts • Paintings • Prints

HORDERN HOUSE RARE BOOKS • MANUSCRIPTS • PAINTINGS • PRINTS A second selection of fine books, maps & graphic material chiefly from THE COLLECTION OF ROBERT EDWARDS AO VOLUME II With a particular focus on inland and coastal exploration in the nineteenth century 77 VICTORIA STREET • POTTS POINT • SYDNEY NSW 2011 • AUSTRALIA TELEPHONE (02) 9356 4411 • FAX (02) 9357 3635 www.hordern.com • [email protected] AN AUSTRALIAN JOURNEY A second volume of Australian books from the collection of Robert Edwards AO n the first large catalogue of books from the library This second volume describes 242 books, almost all of Robert Edwards, published in 2012, we included 19th-century, with just five earlier titles and a handful of a foreword which gave some biographical details of 20th-century books. The subject of the catalogue might IRobert as a significant and influential figure in Australia’s loosely be called Australian Life: the range of subjects modern cultural history. is wide, encompassing politics and policy, exploration, the Australian Aborigines, emigration, convicts and We also tried to provide a picture of him as a collector transportation, the British Parliament and colonial policy, who over many decades assembled an exceptionally wide- with material relating to all the Australian states and ranging and beautiful library with knowledge as well as territories. A choice selection of view books adds to those instinct, and with an unerring taste for condition and which were described in the earlier catalogue with fine importance. In the early years he blazed his own trail with examples of work by Angas, Gill, Westmacott and familiar this sort of collecting, and contributed to the noticeable names such as Leichhardt and Franklin rubbing shoulders shift in biblio-connoisseurship which has marked modern with all manner of explorers, surgeons, historians and other collecting. -

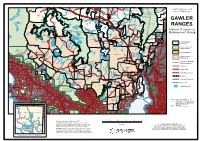

Gawler-Ranges-Nrm-Group-Map.Pdf

WILGENA South Australian Arid BOSWORTH NILPENA ARCOONA Lands NRM Region COONDAMBO LAKE TORRENS NATIONAL PARK NORTH WELL !Woomera GAWLER WIRRAMINNA MOTPENA YELLABINNA KOKATHA REGIONAL RESERVE LAKE TORRENS PERNATTY RANGES LAKE EVERARD ISLAND LAGOON WINTABATINYANA Natural Resources LAKE GAIRDNER Management Group LAKE EVERARD OAKDEN LAKE GAIRDNER HILLS NATIONAL PARK LAKE MAHANEWO SOUTH TORRENS GAP WALLERBERDINA Pastoral Station WORUMBA YALYMBOO Boundary MOONAREE Conservation and National Parks PUREBA CONSERVATION PARK KONDOOLKA YADLAMALKA Aboriginal Land KOOTABERRA YUDNAPINNA PINJARRA NUNNYAH Gawler Ranges CONSERVATION NRM Group RESERVE YARNA & HILTABA WILKATANA KOOLGERA CONSERVATION NONNING PANDURRA ILLEROO SA Arid Lands NRM RESERVE NORTH NORTH Region Boundary YARDEA MT ARDEN ! Willochra Dog Fence KOLENDO ! CARIEWERLOO Quorn Carawa ! ! Wirrulla SIAM Major Road LOCKES NARLABY CLAYPAN Minor Road / Track WARTAKA ILLEROO MOUNT ! IVE Port Augusta Railway ! SCRUBBY Cungena PEAK GAWLER RANGES NATIONAL PARK PANDURRA Cadastral Boundary ! BUCKLEBOO CORUNNA Wilmington Watercourse LAKE GILLES ! Iron Knob CONSERVATION LINCOLN PARK YELTANA UNO RESERVE ! Mainly Dry Lake Smoky Bay BUNGEROO KATUNGA TREGALANA PINKAWILLINIE CONSERVATION PARK ROOPENA CULTANA GILLES DOWNS ! Sceale Bay Iron Baron ! ! MYOLA/ Wudinna ! ! LAKE GILLES IRON BARON Whyalla Port Germein Produced by: Resource Information, Department of Water, CONSERVATION COOYERDOO Land and Biodiversity Conservation. ! PARK Data source: Pastoral lease names and boundaries supplied by Kyancutta ! ! Kimba Pastoral Program, DWLBC. Cadastre and Reserves Baird Bay supplied by the Department for Environment and Heritage. Waterbodies, Roads and Place names supplied by Geoscience Australia. COURTABIE ! ! Venus Bay ! Port Pirie Laura Projection: MGA Zone 53. Datum: Geocentric Datum of Australia, 1994. TALIA SHIRROCOE ! Talia Gladstone ! Marla - Oodnadatta Marree - Innamincka Crystal Brook! 0 10 20 40 60 80 100 Pastoral detail correct to November 2005 Kingoonya North Pastoral Station boundaries shown are based on fence lines. -

KOKATHA ABORIGINAL CORPORATION REGISTERED NATIVE TITLE BODY CORPORATE Corporation Advisory Group Member Role Description Backgro

KOKATHA ABORIGINAL CORPORATION REGISTERED NATIVE TITLE BODY CORPORATE Corporation Advisory Group Member Role Description Background Kokatha Aboriginal Corporation (KAC) was incorporated in 2013 and became a Registered Native Title Body Corporate (RNTBC) when the Kokatha People received Native Title Determination in 2014 over approximately 140,000 km2 of Kokatha land in the northern region of South Australia between Lake Torrens and Lake Gairdner (SCD2014/004 Kokatha People (Part A)). This includes land surrounding Roxby Downs and the Olympic Dam project and also the new gold-copper project at Carrapateena. Special Administration The Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations (ORIC) placed KAC under special administration on 23 September 2019 to initiate and ensure corporate reform. That reform will include a new governance framework and the appointment of a new Board of Directors. ORIC special administrations are for a fixed term and are designed to build capacity and governance capability to enable hand-back of the corporation to its membership. Corporation Advisory Group In special administration, the corporation cannot have a board (that role being taken by the special administrator). Instead, a Corporation Advisory Group (CAG) is formed to work with the special administrator on ‘board-like’ matters. The advisory group is made up of a majority of Aboriginal members, plus specialist independent members appointed through an external recruitment process. Position Function The CAG (and board) does not operate the corporation – that is the role of the General Manager. Members of the Corporation Advisory Group will work with the special administrator on corporation matters such as change strategy, corporate governance, directors’ duties, the rule book and financial oversight. -

Lake Gairdner National Park Draft Management Plan 2019 Minister’Syour Views Foreword Are?????? Important

Lake Gairdner National Park Draft Management Plan 2019 Minister’sYour views Foreword are?????? important ????The Lake Gairdner National Park Co-management Board has developed this plan so that people can express their views about the future management of Lake Gairdner National Park. The Lake Gairdner National Park Draft Management Plan is now released for public comment in accordance with Section 38 of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972. I encourage you to make a submission on this draft plan. Submissions received will assist in the development of a final management plan for the park. Once prepared, the final plan will be forwarded to the Minister for Environment and Water for adoption, together with a detailed analysis of submissions. The Lake Gairdner National Park Co-management Boad encourages all interested people to have their say by making a submission on this draft plan. Guidelines for making a submission can be found on page 15. John Schutz Director of National Parks and Wildlife Cultural sensitivity warning Aboriginal people are warned that this publication may contain culturally sensitive material. 1 Developing this draft plan In 2011, the Federal Court of Australia formally recognised a group of foundational families made up of some, but not all, of the Barngala, Kokatha and Wirangu people as the native title holders over land encompassing Lake Gairdner National Park. This prompted the Gawler Ranges Aboriginal Corporation and the South Australian Government to enter into a co-management agreement for the park, forming the Lake Gairdner National Park Co-management Board. One of the Board’s initial priorities was to review the park management plan which had been in place since 2004. -

Geomorphology of the Acraman Impact Structure, Gawler Ranges, South Australia

Cadernos Lab. Xeolóxico de Laxe Coruña. 2010. Vol. 35, pp. 209 - 220 ISSN: 0213-4497 Geomorphology of the Acraman impact structure, Gawler Ranges, South Australia WILLIAMS, G.E.1 and GOSTIN, V.A. 1 (1) Discipline of Geology and Geophysics, School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia Abstract The late Neoproterozoic Acraman impact structure occurs mostly in felsic volcanic rocks (Mesoproterozoic Gawler Range Volcanics) in the Gawler Ranges, South Australia, and strongly influences the topography of the region. The structure is expressed topographically by three main features: a near-circular, 30 km diameter low-lying area (Acraman Depression) that includes the eccentrically placed Lake Acraman playa; a partly fault-controlled arcuate valley (Yardea Corridor) at 85–90 km diameter; and arcuate features at 150 km diameter that are visible on satellite images. Geological and geomorphological observations and apatite fission-track data indicate that Acraman is eroded several kilometres below the crater floor, with the structure originally comprising a transient cavity about 40 km in diameter and a final structural rim 85–90 km in diameter. Ejecta of shock- deformed fragments of felsic volcanic rock up to 20 cm across derived from the Acraman impact form an extensive horizon ≤40 cm thick in Ediacaran (about 580 Ma) shale in the Adelaide Geosyncline 240–370 km to the east of the impact site. A correlative band ≤7 mm thick of sand-sized ejecta occurs in mudstone in the Officer Basin up to 540 km to the northwest of Acraman. The dimensions of the impact structure and the geochemistry of the ejecta horizon imply that the bolide was a chondritic asteroid >4 km in diameter. -

'SA Incorporated' – Why the Northern 'Family' Worked for So Long

The Working Paper Series SA Incorporated: Leith Yelland Working Paper Lynn Brake Why and how the northern 27 ‘family’ worked for so long 2008 SA Incorporated: Why and how the northern ‘family’ worked for so long Leith Yelland Lynn Brake Contributing author information Leith Yelland is a former manager of the Pastoral Branch and is currently the editor of Across the Outback, which is published for the Outback SA Government and Community Alliances. Lynn Brake was the former Presiding Member of the Arid Areas Catchment Water Management Board, and is a member on the Great Artesian Basin Coordinating Committee. Desert Knowledge CRC Working Paper #27 Information contained in this publication may be copied or reproduced for study, research, information or educational purposes, subject to inclusion of an acknowledgement of the source. ISBN: 1 74158 074 9 (Web copy) ISSN: 1833-7309 (Web copy) Citation Yelland L and Brake L 2008, SA Incorporated: Why and how the northern ‘family’ worked for so long, DKCRC Working Paper 27, Desert Knowledge CRC, Alice Springs. The Desert Knowledge Cooperative Research Centre is an unincorporated joint venture with 28 partners whose mission is to develop and disseminate an understanding of sustainable living in remote desert environments, deliver enduring regional economies and livelihoods based on Desert Knowledge, and create the networks to market this knowledge in other desert lands. Acknowledgements The Desert Knowledge CRC receives funding through the Australian Government Cooperative Research Centres Programme; -

Co-Managing Parks in South Australia 2 Contents

Strong People, Strong Country Co-managing parks in South Australia 2 Contents A journey of…Listening . 2 Traditional belonging . 3 Protecting nature . 3 A journey of…Understanding . 4 What is ‘co-management’? . 5 Working together . 5 A journey of…Respect . 6 Legal framework . 7 Achievements . 8 Our stories: Co-management in South Australia . 10 Arabana Parks Advisory Committee . 12 Gawler Ranges National Park Advisory Committee . 14 Ikara–Flinders Ranges National Park Co-management Board . 16 Kanku–Breakaways Conservation Park Co-management Board . .18 Lake Gairdner National Park Co-management Board . 20 Mamungari Conservation Park Co-management Board . 22 Ngaut Ngaut Conservation Park Co-management Board . 24 Nullarbor Parks Advisory Committee . 26 Vulkathunha–Gammon Ranges National Park Co-management Board . .28 Witjira National Park Co-management Board . 30 Yandruwandha Yawarrawarrka Parks Advisory Committee . 32 Yumbarra Conservation Park Co-management Board . 34 Acknowledgements . 36 Bibliography . 36 Strong People, Strong Country 1 A journey of... listening We meet around the table with different stories and histories; co-management helps us develop shared contemporary visions for the future of the country. Matt Ward, DEW Regional Manager, Natural Resources Alinytjara Wilurara 2 Traditional belonging Protecting nature ”By reconnecting people to their land in a way “Co-management is a new way of working that benefits them, culture becomes strong again” together; a new way to care for our parks” Leonard Miller Snr, Yumbarra John Schutz, Director of National Parks and Wildlife Aboriginal Australians have an intrinsic connection to their South Australia’s protected area system, which safeguards areas ancestral lands; while each community is distinct, they share of conservation and biodiversity significance, includes over 340 a common fundamental belief that their health and wellbeing reserves that together cover more than 21 million hectares, or cannot be separated from the health and wellbeing of their 21% of the State. -

Draft Recovery Plan for 23 Threatened Flora Taxa on Eyre Peninsula, South Australia

Department for Environment and Heritage DRAFT RECOVERY PLAN FOR 23 THREATENED FLORA TAXA ON EYRE PENINSULA, SOUTH AUSTRALIA 2007-2012 www.environment.sa.gov.au Acknowledgements Thank you to the following people for the information, comments and assistance provided in the preparation of this recovery plan: • Anthony Freebairn (Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australia) for the preparation of an earlier draft of this recovery plan and significant contribution to early recovery actions in his former role as Threatened Flora Project Officer • Snow Burton, Sally Deslandes, Chris Deslandes, Pam Hewstone and Jane Hutchinson (community contributors and volunteers) • Phil Ainsley, David Armstrong, Geoff Axford, Doug Bickerton, Peter Copley, Nigel Cotsell, Toula Ellis, Tom Gerschwitz, Louisa Halliday, Bill Haddrill, Mary-Anne Healy, Amy Ide, Manfred Jusaitis, Paula Peeters, Joe Quarmby, Joe Tilley, Birgitte Sorensen, Karan Smith, Renate Velzeboer, Helen Vonow, Sarah Way and Mike Wouters (Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australia) • Anthelia Bond (previously Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australia) • Geraldine Turner and Nicole Reichelt (Landcare, Eyre Peninsula) • Robert Coventry, Andrew Freeman, Iggy Honan, Rachael Kannussaar, Peter Sheridan and Tony Zwar (Eyre Peninsula Natural Resources Management Board) • Tim Reynolds (Department for Transport, Energy and Infrastructure) • Tim Jury and Yvonne Steed (Threatened Plant Action Group) • Simon Bey (Greening Australia) and Melissa Horgan (previously Greening