Shel Dorf Sky Masters Al Williamson the Eternals Mike Thibodeaux Machine Man, Captain Victory, 2001, Starman Zero, Silver Surfer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eerie Archives: Volume 16 Free

FREE EERIE ARCHIVES: VOLUME 16 PDF Bill DuBay,Louise Jones,Faculty of Classics James Warren | 294 pages | 12 Jun 2014 | DARK HORSE COMICS | 9781616554002 | English | Milwaukee, United States Eerie (Volume) - Comic Vine Gather up your wooden stakes, your blood-covered hatchets, and all the skeletons in the darkest depths of your closet, and prepare for a horrifying adventure into the darkest corners of comics history. This vein-chilling second volume showcases work by Eerie Archives: Volume 16 of the best artists to ever work in the comics medium, including Alex Toth, Gray Morrow, Reed Crandall, John Severin, and others. Grab your bleeding glasses and crack open this fourth big volume, collecting Creepy issues Creepy Archives Volume 5 continues the critically acclaimed series that throws back the dusty curtain on a treasure trove of amazing comics art and brilliantly blood-chilling stories. Dark Horse Comics continues to showcase its dedication to publishing the greatest comics of all time with the release of the sixth spooky volume Eerie Archives: Volume 16 our Creepy magazine archives. Creepy Archives Volume 7 collects a Eerie Archives: Volume 16 array of stories from the second great generation of artists and writers in Eerie Archives: Volume 16 history of the world's best illustrated horror magazine. As the s ended and the '70s began, the original, classic creative lineup for Creepy was eventually infused with a slew of new talent, with phenomenal new contributors like Richard Corben, Ken Kelly, and Nicola Cuti joining the ranks of established greats like Reed Crandall, Frank Frazetta, and Al Williamson. This volume of the Creepy Archives series collects more than two hundred pages of distinctive short horror comics in a gorgeous hardcover format. -

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received 88-91 This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessinglUMI the World’s Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Mi 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8820263 Leigh Brackett: American science fiction writer—her life and work Carr, John Leonard, Ph.D. -

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Superman's Girl Friend, Lois Lane and the Represe

Research Space Journal article ‘Superman believes that a wife’s place is in the home’: Superman’s girl friend, Lois Lane and the representation of women Goodrum, M. Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Please cite this publication as follows: Goodrum, M. (2018) ‘Superman believes that a wife’s place is in the home’: Superman’s girl friend, Lois Lane and the representation of women. Gender & History, 30 (2). ISSN 1468-0424. Link to official URL (if available): https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0424.12361 This version is made available in accordance with publishers’ policies. All material made available by CReaTE is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Contact: [email protected] ‘Superman believes that a wife’s place is in the home’: Superman’s Girl Friend, Lois Lane and the representation of women Michael Goodrum Superman’s Girl Friend, Lois Lane ran from 1958-1974 and stands as a microcosm of contemporary debates about women and their place in American society. The title itself suggests many of the topics about which women were concerned, or at least were supposed to concern them: the mediation of identity through heterosexual partnership, the pressure to marry and the simultaneous emphasis placed on individual achievement. Concerns about marriage and Lois’ ability to enter into it routinely provide the sole narrative dynamic for stories and Superman engages in different methods of avoiding the matrimonial schemes devised by Lois or her main romantic rival, Lana Lang. -

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

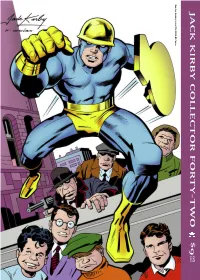

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR FORTY-TWO $9 95 IN THE US Guardian, Newsboy Legion TM & ©2005 DC Comics. Contents THE NEW OPENING SHOT . .2 (take a trip down Lois Lane) UNDER THE COVERS . .4 (we cover our covers’ creation) JACK F.A.Q. s . .6 (Mark Evanier spills the beans on ISSUE #42, SPRING 2005 Jack’s favorite food and more) Collector INNERVIEW . .12 Jack created a pair of custom pencil drawings of the Guardian and Newsboy Legion for the endpapers (Kirby teaches us to speak the language of the ’70s) of his personal bound volume of Star-Spangled Comics #7-15. We combined the two pieces to create this drawing for our MISSING LINKS . .19 front cover, which Kevin Nowlan inked. Delete the (where’d the Guardian go?) Newsboys’ heads (taken from the second drawing) to RETROSPECTIVE . .20 see what Jack’s original drawing looked like. (with friends like Jimmy Olsen...) Characters TM & ©2005 DC Comics. QUIPS ’N’ Q&A’S . .22 (Radioactive Man goes Bongo in the Fourth World) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . .25 (creating the Silver Surfer & Galactus? All in a day’s work) ANALYSIS . .26 (linking Jimmy Olsen, Spirit World, and Neal Adams) VIEW FROM THE WHIZ WAGON . .31 (visit the FF movie set, where Kirby abounds; but will he get credited?) KIRBY AS A GENRE . .34 (Adam McGovern goes Italian) HEADLINERS . .36 (the ultimate look at the Newsboy Legion’s appearances) KIRBY OBSCURA . .48 (’50s and ’60s Kirby uncovered) GALLERY 1 . .50 (we tell tales of the DNA Project in pencil form) PUBLIC DOMAIN THEATRE . .60 (a new regular feature, present - ing complete Kirby stories that won’t get us sued) KIRBY AS A GENRE: EXTRA! . -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Fantastic Four Compendium

MA4 6889 Advanced Game Official Accessory The FANTASTIC FOUR™ Compendium by David E. Martin All Marvel characters and the distinctive likenesses thereof The names of characters used herein are fictitious and do are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. not refer to any person living or dead. Any descriptions MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS including similarities to persons living or dead are merely co- are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. incidental. PRODUCTS OF YOUR IMAGINATION and the ©Copyright 1987 Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. All TSR logo are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. Game Design Rights Reserved. Printed in USA. PDF version 1.0, 2000. ©1987 TSR, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents Introduction . 2 A Brief History of the FANTASTIC FOUR . 2 The Fantastic Four . 3 Friends of the FF. 11 Races and Organizations . 25 Fiends and Foes . 38 Travel Guide . 76 Vehicles . 93 “From The Beginning Comes the End!” — A Fantastic Four Adventure . 96 Index. 102 This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or other unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written consent of TSR, Inc., and Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc., and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. All characters appearing in this gamebook and the distinctive likenesses thereof are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. -

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

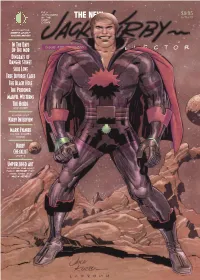

Fully $9.95 Authorized THE NEW By The In The US Kirby Estate SPOTLIGHTING KIRBY’S LEAST- KNOWN WORK! In The Days Of The Mob ISSUE #32, JULY 2001 Collector Dingbats of Danger Street Soul Love True Divorce Cases The Black Hole The Prisoner Marvel Westerns The Horde and more! A Long-Lost Kirby Interview Mark Evanier on the Fourth World Kirby Checklist UPDATE Unpublished Art including published pages Before They Were Inked, And Much More!! Contents OPENING SHOT . .2 THE NEW (to those who say “We don’t need no stinkin’ unknown Kirby work”, the editor politely says “Phooey”) UNDER THE COVERS . .4 (the story behind the somewhat Glen Campbell-looking fellow on our covers) JACK F.A.Q. s . .6 (Mark Evanier answers a reader’s ISSUE #32, JULY 2001 Collector Frequently Asked Questions about the Fourth World) ANIMATED GESTURES . .11 (Eric Nolen-Weathington begins his ongoing crusade to make sense of some of the animation art Kirby drew) IN HIS OWN WORDS . .12 (Kirby speaks in this long-lost interview from France—oui!) CREDIT CHECK . .22 (Kirby sets a new record, as we present the long-awaited update to the Kirby Checklist, courtesy of Richard Kolkman) GALLERY . .32 (some of Kirby’s least-known and/or never-seen art gets its day in the sun) KIRBY AS A GENRE . .44 (Adam McGovern takes another swat at those pesky Kirby homages that are swarming around his mailbox) INTERNATIONALITIES . .46 (this issue’s look at Jack’s international influence finds Jean-Marie Arnon owes the King a huge debt) TRIVIA . -

PRICES REALIZED DETAIL - Frazetta Auction 79, Auction Date

26662 Agoura Road, Calabasas, CA 91302 Tel: 310.859.7701 Fax: 310.859.3842 PRICES REALIZED DETAIL - Frazetta Auction 79, Auction Date: LOT ITEM PRICE PREMIUM 1 (FRAZETTA) TARZAN THE INVINCIBLE. $65,000 $13,000 2 (FRAZETTA) TARZAN AT THE EARTH’S CORE. $55,000 $11,000 3 (FRAZETTA) SUMMER OF THE COUP. $35,000 $7,000 4 (FRAZETTA) THE LION QUEEN. $140,000 $39,200 5 (FRAZETTA) CONAN AND THE SAVAGE SEA (CONAN THE BUCCANEER). $15,000 $3,000 6 (FRAZETTA) ABSTRACT. $2,000 $400 7 (FRAZETTA) FLASH GORDON “BATTLES THE MONSTER FROM MONGO”. $55,000 $15,400 8 (FRAZETTA) FLASH GORDON AND “PRINCESS OF MONGO”. $32,500 $6,500 9 (FRAZETTA) A GENTLE BREEZE. $60,000 $16,800 10 (FRAZETTA) WINDBLOWN. $20,000 $4,000 11 (FRAZETTA) SELF-PORTRAIT #1. $15,000 $3,000 12 (FRAZETTA) SELF-PORTRAIT #2. $5,000 $1,000 13 (FRAZETTA) TARZAN AT THE EARTH’S CORE COVER. $40,000 $8,000 14 (FRAZETTA) TARZAN AND THE CASTAWAYS COVER. $85,000 $23,800 15 (FRAZETTA) TARZAN AND THE CASTAWAYS. $30,000 $8,400 16 (FRAZETTA) TARZAN AND THE GOLDEN LION. $55,000 $11,000 Page 1 of 8 26662 Agoura Road, Calabasas, CA 91302 Tel: 310.859.7701 Fax: 310.859.3842 PRICES REALIZED DETAIL - Frazetta Auction 79, Auction Date: LOT ITEM PRICE PREMIUM 17 (FRAZETTA) LORD OF THE SAVAGE JUNGLE. $100,000 $28,000 18 (FRAZETTA) AT EARTH’S CORE. $32,500 $6,500 19 (FRAZETTA) AT THE EARTH’S CORE. $40,000 $8,000 20 (FRAZETTA) KUBLA KHAN PORTFOLIO. $55,000 $11,000 21 (FRAZETTA) KUBLA KHAN PORTFOLIO. -

Captain Marvel Crossword

Name: Date: CAPTAIN MARVEL CROSSWORD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 ACROSS DOWN 1. The Prime, the Deviants and the Eternals are 2. A close friend that shared a number of adventures three kind of... together. 7. Real Name of Captain Marvel 3. She joined this agency upon graduating from high 9. Captain Marvel leaved her troubles with X-Men on school to pursue her dreams of flying. Earth behind to join space pirates called... 4. Ms. Marvel is also known as... 10. Humanoid alien race descendant of bird-like 5. Enemy that vowed to destroy Ms. Marvel. creatures Shi'ar and enemy of Ms. Marvel. 6. Because of Carol's stellar performance, superb 11. Who performed experiments on Carol’s genetic combat skills and natural intellect, she was structure that unleashed the full potential of recruited by... cosmic power? 8. Ms. Marvel joined and helped them many times. 12. Carol’s genetic structure was changed by an explosion to a perfect hybrid of human and ____________ genes. DEATHBIRD MYSTIQUE KREE AIR FORCE C.I.A. SKRULLS LOGAN STARJAMMERS CAROL DANVERS BINARY BROOD AVENGERS Free Printable Crossword www.AllFreePrintable.com Name: Date: CAPTAIN MARVEL CROSSWORD 1 2 S K R U L L S 3 O A 4 B G I 5 6 7 8 M C I C A R O L D A N V E R S Y I N V N F 9 S T A R J A M M E R S O T R N R 10 D E A T H B I R D Y G C Q E E 11 U B R O O D 12 K R E E S ACROSS DOWN 1. -

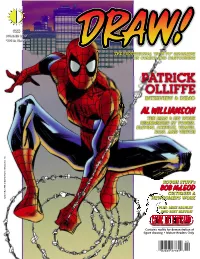

Patrick Olliffe Interview & Demo Al Williamson the Man & His Work Remembered by Torres, Blevins, Schultz, Yeates, Ross, and Veitch

#23 SUMMER 2012 $7.95 In The US THE PROFESSIONAL “HOW-TO” MAGAZINE ON COMICS AND CARTOONING PATRICK OLLIFFE INTERVIEW & DEMO AL WILLIAMSON THE MAN & HIS WORK REMEMBERED BY TORRES, BLEVINS, SCHULTZ, YEATES, ROSS, AND VEITCH ROUGH STUFF’s BOB McLEOD CRITIQUES A Spider-Man TM Spider-Man & ©2012 Marvel Characters, Inc. NEWCOMER’S WORK PLUS: MIKE MANLEY AND BRET BLEVINS’ Contains nudity for demonstration of figure drawing • Mature Readers Only 0 2 1 82658 27764 2 THE PROFESSIONAL “HOW-TO” MAGAZINE ON COMICS & CARTOONING WWW.DRAW-MAGAZINE.BLOGSPOT.COM SUMMER 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS VOL. 1, NO. 23 Editor-in-Chief • Michael Manley Designer • Eric Nolen-Weathington PAT OLLIFFE Publisher • John Morrow Mike Manley interviews the artist about his career and working with Al Williamson Logo Design • John Costanza 3 Copy-Editing • Eric Nolen- Weathington Front Cover • Pat Olliffe DRAW! Summer 2012, Vol. 1, No. 23 was produced by Action Planet, Inc. and published by TwoMorrows Publishing. ROUGH CRITIQUE Michael Manley, Editor. John Morrow, Publisher. Bob McLeod gives practical advice and Editorial address: DRAW! Magazine, c/o Michael Manley, 430 Spruce Ave., Upper Darby, PA 19082. 22 tips on how to improve your work Subscription Address: TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Dr., Raleigh, NC 27614. DRAW! and its logo are trademarks of Action Planet, Inc. All contributions herein are copyright 2012 by their respective contributors. Action Planet, Inc. and TwoMorrows Publishing accept no responsibility for unsolicited submissions. All artwork herein is copyright the year of produc- THE CRUSTY CRITIC tion, its creator (if work-for-hire, the entity which Jamar Nicholas reviews the tools of the trade.