August 2008 1400 AM WAMC - Host: Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

59, Ph.D. AMC Class of 2017 Residency Matches

Fall 2017 Program Update—Ed LaRow ’59, Ph.D. We welcomed yet comprised 27% of the Honors A Committee of Siena and AMC 14 members for Graduates, received 24% of the faculty and administrators met during the Class of awards and made up 17% of AOA the summer and fall of 2016 to 2021, this is the (their residencies are listed below). develop a transition plan for the nd st 32 class to The 31 annual picnic was held at program. Two major changes have begin their Serra Manor and was the most been recommended and put in place. eight-year successful to date. We had 90 All planning and logistics for the journey to the attendees that included 35 medical Summer of Service will be handled MD Degree. students and two of the most recent by the International Studies Office This is a talented graduates. group of individuals selected from a and AMC will play a greater role in Sharon Hsu and Monica Hanna national pool of 468 applicants. We the selection of the class. Siena will planned a surprise 30th anniversary currently have 108 students in the still make the final decision as to who pipeline – 59 at Siena and 49 at party that had 100 students, faculty will be interviewed for the program. AMC. To date, 237 have received and friends show up for the We have initiated a feature their MD degrees. The Class of celebration. There was an elaborate highlighting accomplishments of ‘13/’17 did Siena proud at the most ruse to keep me in the dark about the program alumni… any suggestions recent AMC graduation. -

WAMC Staff Our Weekly Schedule of Programming

FEBRUARY 2018 PROGRAM GUIDE Stations Help WAMC Go Green! from alan You may elect to stop receiving our paper Monthly column from Alan Chartock. WAMC, 90.3 FM, Albany, NY program guide, and view it on wamc.org. PAGE 2 WAMC 1400 AM, Albany, NY Call us to be removed from the mailing list: WAMK, 90.9 FM, Kingston, NY 1-800-323-9262 ext. 133 PROGRAM NOTES WOSR, 91.7 FM, Middletown, NY PAGE 3 WCEL, 91.9 FM, Plattsburgh, NY PROGRAM SCHEDULE WCAN, 93.3 FM, Canajoharie, NY WAMC Staff Our weekly schedule of programming. WANC, 103.9 FM, Ticonderoga, NY PAGE 4 WRUN-FM, 90.3 FM, Remsen- WAMC Executive Staff Utica, NY WAMQ, 105.1 FM, Great Barrington, Alan Chartock | President and CEO LIVE AT THE LINDA BROADCAST MA Joe Donahue | Senior Director of WWES, 88.9 FM, Mt. Kisco, NY News and Programming Stacey Rosenberry | Director of Operations SCHEDULE WANR, 88.5 FM, Brewster, NY and Engineering Listen to your favorite shows on air after WANZ, 90.1, Stamford, NY they have been at The Linda. Holly Urban | Chief Financial Officer PAGE 5 Translators At the linda Management Staff PAGE 6 W280DJ, 103.9 FM, Beacon, NY Carl Blackwood | The Linda Manager W247BM, 97.3 FM, Cooperstown, Kristin Gilbert | Program Director and NY Traffic Manager program descriptions W292ES, 106.3 FM, Dover Plains, Melissa Kees | Underwriting Manager PAGE 7 NY Ashleigh Kinsey | Digital Media W243BZ, 96.5 FM, Ellenville, NY Administrator W271BF, 102.1 FM, Highland, NY Colleen O’Connell | Fund Drive our UNDERWRITERS Manager W246BJ, 97.1 FM, Hudson, NY PAGE 11 Ian Pickus | News Director W204CJ, 88.7 FM, Lake Placid, NY Amber Sickles | Membership Director W292DX, 106.3 FM, Middletown, NY WAMC-FM broadcasts 365 days a year W215BG, 90.9 FM, Milford, PA WAMC to eastern New York and western New W299AG, 107.7 FM, Newburgh, NY Box 66600 England on 90.3 MHz. -

An Overview Albany Medical Center

An Overview Albany Medical Center Recognizing the need for improved management capabilities and integration of systems, the Albany Medical College and the Albany Medical Center Hospital entered into a new organizational structure known as Albany Medical Center in Albany Medical College 1983. The Center consolidated planning, finances, fund raising, and policy direction for the College and Hospital, Albany Medical College, one of the nation’s oldest private assuring that the two institutions pursue appropriately medical schools, prides itself in offering an intimate, collegial integrated and reinforced missions in health care, education, environment, which fosters humane values and genuine and biomedical research. This Institutional configuration has learning. The Albany Medical College enrolled its first allowed Albany Medical Center to become a well developed students in 1839, however, the impetus for this institution may academic medical center serving as a regional resource for be traced to 1821 when the founder of the college and first twenty-four counties in northeastern New York and west- Dean, Alden March, opened a one-room school and began central New England. offering courses in Anatomy. Every year from the mid-1820s until 1838, Dr. March submitted petitions to the New York The Medical Center is Albany’s largest non-governmental State Legislature to establish an Albany Medical College. In employer with approximately 6,000 employees. The Center is 1830, he delivered “A Lecture on the Expediency of at the hub of a health care network that includes 50 hospitals Establishing a Medical College and Hospital in the City of and more than 3,000 physicians in its 24-county service Albany.” Support from citizen committees and the City of region. -

Mark E. Snyder, Mt(Ascp), Qli [email protected] (518) 320-8302

SLINGERLANDS, NY 12159 MARK E. SNYDER, MT(ASCP), QLI [email protected] (518) 320-8302 OBJECTIVE Seeking additional full or part-time MEDITECH LAB or PHA remote support positions. Skills MEDITECH MEDITECH LAB EDUCATION MEDITECH PHA MEDITECH OE MEDITECH OPS Health Services Administration, Master of Science May 1991 MEDITECH MIS Russell Sage College, Evening Division, Albany, New York MEDITECH NPR MEDITECH NMI Biology, Master of Science May 1980 SUNQUEST College of St. Rose, Albany, New York Upgrades (Ring Release) Medical Technology, Bachelor of Science May 1975 Implementations SUNY at Albany/Albany Medical Center School of Medical Technology, Albany, New York MS Office Suite Windows Vista/XP EXPERIENCE LAB SUPERVISION MEDITECH LAB/PHA Support Analyst August 2006 – December 2011 LAB INSPECTIONS Sutter Healthcare Central Valley Region, Modesto, California NY STATE LAB REGS Contracted with Beacon Partners CLIA REGS Provided remote support to three hospital laboratories and two pharmacies for their MEDITECH Certifications Magic V5.63 applications. Support included dictionary maintenance, troubleshooting, analyzer interface setups, reference lab interface monitoring, and PYXIS interface monitoring and MT(ASCP) – 1975 troubleshooting. I also provided On-Call support for all MEDITECH modules (NUR, PCI, OE, RAD, ADM, BAR, NPR, MIS, OPS, and MOX) every five weeks. The support ended when the sites QLI (Qualification converted to EPIC. in Lab Informatics)- 2006 MEDITECH LAB Support Analyst June 2010 –Present Special Training Promise Healthcare, Boca Raton, Florida Contracted with Dell Services Adv. NPR Report Writer Training- Providing remote LAB support to ten MEDITECH Client Server V5.55 hospitals that are part of the 2005 Promise Health Care chain. -

The AMC Experience Still Growing

(She Albany Hetitral Nrnta Vol. 1, No. 1 The Student Newspaper of Albany Medical College Albany, N.Y., Tuesday, September 5,1978 AMA Student Section Reorganization Effected Debakey, “Aortocoronary-Artery By ARTHUR W. PERRY ’81 Bypass: Assessment After 13 The Student Business Section years,” which appeared in JAM A (SBS) of the American Medical February 27, 1978. Both speakers Association convened for its treated the students to a frank annual meeting on Saturday debate, which at times became morning, June 17th, at the Chase- heated to the point of viciousness. Park Plaza Hotel in St. Louis, AMA-SBS vs. AMSA Missouri. The SBS is composed The second segment of the of representatives from each of meeting was the Business Session. the US Medical Schools. Its Following the traditional opening purpose is to give students direct remarks, which included a report input to the workings or that students are now permitted organized medicine via their one to attend the AMA Board of representative who is a voting Trustees meetings, a lengthy and member of the AMA House of somewhat heated discussion on Delegates, the legislative body of the internal structure of the SBS the Association. Any member of was held. The controversy the SBS may submit a resolution centered around the amount of which is then discussed and voted input to the SBS that the on by the SBS. If approved, it is American Medical Student then introduced for consideration Association (AMSA), a separate by the House. organization, should have. The SBS meeting was divided Previously, AMSA had appointed into three segments. -

Anthony Santella) 3/1/20-2/28/21 Prep Long Island: a Peer Change Agent Intervention $35,000/ 1 Year Role: Principal Investigator 3

CURRICULUM VITAE ANTHONY J. SANTELLA GENERAL INFORMATION Address: Hofstra Dome 126, Hofstra University, Hempstead, NY 11549 (office) Telephone: (516) 463-5932 (office) or (917) 545-4121 (mobile) Email: [email protected] or [email protected] Website: www.anthonyjsantella.com EDUCATION YEAR DEGREE INSTITUTION FIELD OF STUDY 2015-2017 Graduate Hofstra University Health Professions Advanced Hempstead, NY Pedagogy and Certificate Leadership 2005-2007 Doctor of Tulane University Health Systems Public Health New Orleans, LA Management Dissertation: Predictors of Hospital Length of Stay, Mortality, and Total Charges Among HIV-Infected Adults in Louisiana 2003-2004 Master of Emory University Health Policy and Public Health Atlanta, GA Management Culminating Project: Analysis of Recruitment Strategy Costs for Preventive HIV Vaccine Trials 1997-2001 Bachelor of University of Biomedical Sciences Science Connecticut Storrs, CT CERTIFICATIONS 2015 Master National Commission Advanced-level CHES on Health Education Health Education (MCHES) Credentialing Whitehall, PA WORK EXPERIENCE 2014-present Associate Professor of Public Health with tenure (2017 -present) Programs: Master of Public Health, BS in Health Sciences, BS in Community Health, and LGBTQ+ Studies minor Assistant Professor of Public Health (2014-2017) School of Health Professions and Human Services Hofstra University Hempstead, New York 1 2014-present Consultant, Anthony J. Santella Consulting, LLC (since 2018) Certified LGBT Business Enterprise® from the National LGBT Chamber -

COE Facilities

Institutes of Quality® Quality care made simple. Sometimes surgery is the best choice for your health. But all surgery carries some level of risk, so it’s important to look for facilities known for quality care. We’ve simplified the process. As a member, you have a special network of hospitals and other facilities that specialize in certain procedures: • Cardiac (for the heart) • Orthopedic (for the joints and spine) • Bariatric (for weight loss) We call these facilities our Institutes of Quality (IOQ for short). Facilities earn IOQ status for having high volumes and producing clear clinical results in their area of specialty. This delivers value and quality to members, so you can get back to living your life. IOQ requirements were created by working with experts on these health conditions. You can review these requirements at: aetna.com/provider/medical/resource_ med/business_med/institutes.html Special Notes You may need preauthorization for these services. Please see our Clinical Policy Bulletins located at https://www.aetna.com/health-care-professionals/ clinical-policy-bulletins/medical-clinical-policy-bulletins.html. Not all Institutes of Quality services are covered by all health plans. To find out if a facility is a network provider in your plan, please log in or register now to get search results based on your plan or you can start a new search and select an Aetna plan at aetna.com/dse/search?site_id=docfind&langpref=en&tabKey=tab1. Some of the Institutes of Quality do not have doctors who contract with Aetna. You may have to pay extra if you use a center that does not have doctors who contract with Aetna. -

Albany Medical Center

PROJECT PROFILE Albany Medical Center 4.6 MW CHP System Quick Facts LOCATION: Albany, NY MARKET SECTOR: Hospitals FACILITY PEAK LOAD: 8 MW EQUIPMENT: 4.6 MW Solar Turbine Mercury 50-6000R recuperated gas turbine FUEL: Natural Gas USE OF THERMAL ENERGY: Space heating and cooling, domestic hot water, sterilization, healthcare processes CHP TOTAL EFFICIENCY: 84% ENVIRONMENTAL BENEFIT: 20,000 ton annual reduction in CO2 emissions TOTAL PROJECT COST: $23 million PAYBACK: 7-9 years CHP IN OPERATION SINCE: 2013 NOTE: Received 2015 Build NY Award from Location of CHP plant at Albany Medical Center, Albany, NY Associated General Contractors of NY COURTESY OF Cogen Power Technologies State Site Description Albany Medical Center in downtown Albany, NY encompasses the 651-bed Albany Medical Center Hospital, as well as the 550-student Albany Medical College. It is a Level-I Trauma center, and the only academic health sciences center in Northeastern New York State. In 2013, Albany Medical Center underwent a $330 million expansion of the Medical Center Hospital. Not only does the expansion allow for state-of-the-art services, it also allowed Albany Medical Center to become the first hospital in the region to attain LEED Gold Certification, in part due to its incorporation of CHP. Reasons for CHP To meet the increased power needs from the expansion, Albany Medical Center Hospital chose to invest in a CHP plant. Because of its urban location, the available space for power generation is tightly constrained, and Albany Medical Center wanted to ensure they could meet the needs of their current and future expansions. -

Air Medical Services Utilization Guidelines

INTRODUCTION The Hudson Valley–Westchester Helicopter subcommittee is an inter-regional advisory group established by the Hudson Valley and Westchester Regional EMS Councils and the local Air Medical Services (AMS). This guideline is provided to all emergency service agencies: law enforcement, fire departments, and emergency medical services (EMS) in the lower seven counties of the Hudson River Valley (geographically north to south, west to east) – Sullivan, Ulster, Dutchess, Orange, Putnam, Rockland, and Westchester. The helicopter is an air ambulance and an essential part of the EMS system. In today’s environment of increasingly scarce EMS resources, appropriate use of AMS is of the utmost importance. Adherence to the practices included in this guideline will help to ensure that the proper resources are provided to the right patients at the right time while maintaining safe and efficient EMS operations. OPERATIONAL CRITERIA FOR REQUESTING AIR MEDICAL SERVICES The following operational criteria must be met prior to requesting a helicopter for scene response: 1. The patient can arrive at the closest appropriate facility faster by air than by ground transport. 2. A safe helicopter-landing site is available. Ground providers should notify dispatch if more than one patient requires air transport. If available, one helicopter will be dispatched per critical patient requiring air transport. CLINICAL CRITERIA FOR REQUESTING AIR MEDICAL SERVICES 1. The patient needs and/or would benefit from the clinical capability of the AMS team. 2. A patient in cardiac arrest may be transported by AMS if already responding and the transport to the closest hospital would be faster by air than ground. -

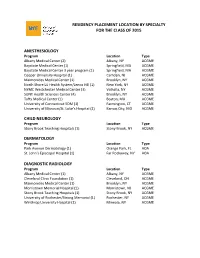

Residency Placement Location by Specialty for the Class of 2015

RESIDENCY PLACEMENT LOCATION BY SPECIALTY FOR THE CLASS OF 2015 ANESTHESIOLOGY Program Location Type Albany Medical Center (2) Albany, NY ACGME Baystate Medical Center (1) Springfield, MA ACGME Baystate Medical Center 3 year program (1) Springfield, MA ACGME Cooper University Hospital (1) Camden, NJ ACGME Maimonides Medical Center (1) Brooklyn, NY ACGME North Shore LIJ Health System/Lenox Hill (1) New York, NY ACGME NYMC Westchester Medical Center (3) Valhalla, NY ACGME SUNY Health Sciences Center (4) Brooklyn, NY ACGME Tufts Medical Center (1) Boston, MA ACGME University of Connecticut SOM (1) Farmington, CT ACGME University of Missouri/St. Luke’s Hospital (1) Kansas City, MO ACGME CHILD NEUROLOGY Program Location Type Stony Brook Teaching Hospitals (1) Stony Brook, NY ACGME DERMATOLOGY Program Location Type Park Avenue Dermatology (1) Orange Park, FL AOA St. John’s Episcopal Hospital (1) Far Rockaway, NY AOA DIAGNOSTIC RADIOLOGY Program Location Type Albany Medical Center (1) Albany, NY ACGME Cleveland Clinic Foundation (1) Cleveland, OH ACGME Maimonides Medical Center (1) Brooklyn, NY ACGME Morristown Memorial Hospital (1) Morristown, NJ ACGME Stony Brook Teaching Hospitals (1) Stony Brook, NY ACGME University of Rochester/Strong Memorial (1) Rochester, NY ACGME Winthrop University Hospital (1) Mineola, NY ACGME EMERGENCY MEDICINE Program Location Type Albany Medical Center (1) Albany, NY ACGME Brooklyn Hospital Center (1) Brooklyn, NY ACGME Coney Island Hospital (1) Brooklyn, NY AOA Good Samaritan Hospital and MC (1) West Islip, NY AOA Hofstra NSLIJ-Lenox Hill (1) New York, NY ACGME Inspira Health Network (2) Vineland, NJ AOA Kennedy U/Our Lady of Lourdes (1) Stratford, NJ AOA LECOM/Elizabeth Boardman (1) Youngstown, OH AOA Maimonides Medical Center (1) Brooklyn, NY ACGME Morristown Memorial Hospital (1) Morristown, NJ ACGME Nassau University Medical Center (2) East Meadow, NY AOA Naval Hospital (1) Portsmouth, VA Military Newark BI/St. -

Albany Med Today December 2017.Indd

VOLUME 12 NUMBER 12 | DECEMBER 2017 ALBANY MED Avril Moncrieffe, PSA KNOWN FOR OUR EXPERTISE. CHOSEN FOR OUR CARE. Environmental Services TODAY Team Honored / p. 2 Study on Opioid Use in Emergency Medicine Garners Widespread Attention Andrew Chang, MD, MS, the combinations given and found randomized, double-blind clinical Vincent P. Verdile, MD, ’84 Endowed patients experienced little diff erence trial. Consented participants Chair for Emergency Medicine, in pain relief after two hours. were given a single dose of one has authored a study on painkillers of four oral analgesics (ibuprofen, administered in an emergency “Our results of no diff erence in pain oxycodone, hydrocodone, or department (ED) setting that shows relief while the patient is still in the codeine), all combined with similar pain reduction off ered by ED imply that patients may be more acetaminophen, and were asked three diff erent opioids and one accepting of a non-opioid upon to rate their pain intensity from 0 non-opioid combination analgesic. discharge—and clinicians may feel to 10 upon ingestion, and at one- e study, which was published in less pressure to prescribe opioids to and two-hour intervals following the Journal of the American Medical patients leaving the ED,” he said. ingestion while still in the ED. Association, has the potential to aff ect “If we can decrease the number of the way opioids are given in ED patients being exposed to opioids, Of 411 patients, baseline pain settings and has added signifi cant fuel then perhaps we can decrease the intensity was initially high at mean it is true for every patient.” to the ongoing national discussion number of patients who will become 8.7. -

WAMC Staff Our Weekly Schedule of Programming

MARCH 2019 PROGRAM GUIDE Stations Help WAMC Go Green! from alan You may elect to stop receiving our paper Monthly column from Alan Chartock. WAMC, 90.3 FM, Albany, NY program guide, and view it on wamc.org. PAGE 2 WAMC 1400 AM, Albany, NY Call us to be removed from the mailing list: WAMK, 90.9 FM, Kingston, NY 1-800-323-9262 ext. 133 PROGRAM NOTES WOSR, 91.7 FM, Middletown, NY PAGE 3 WCEL, 91.9 FM, Plattsburgh, NY PROGRAM SCHEDULE WCAN, 93.3 FM, Canajoharie, NY WAMC Staff Our weekly schedule of programming. WANC, 103.9 FM, Ticonderoga, NY PAGE 4 WRUN-FM, 90.3 FM, Remsen- WAMC Executive Staff Utica, NY WAMQ, 105.1 FM, Great Barrington, Alan Chartock | President and CEO LIVE AT THE LINDA BROADCAST MA Joe Donahue | Senior Director of WWES, 88.9 FM, Mt. Kisco, NY News and Programming Stacey Rosenberry | Director of Operations SCHEDULE WANR, 88.5 FM, Brewster, NY and Engineering Listen to your favorite shows on air after WANZ, 90.1, Stamford, NY they have been at The Linda. Jordan Yoxall | Chief Financial Officer PAGE 5 Translators At the linda Management Staff PAGE 6 W280DJ, 103.9 FM, Beacon, NY Carl Blackwood | The Linda Manager W247BM, 97.3 FM, Cooperstown, David Hopper | Interim Program Director NY Melissa Kees | Underwriting Manager program descriptions W292ES, 106.3 FM, Dover Plains, Ashleigh Kinsey | Digital Media PAGE 7 NY Administrator W243BZ, 96.5 FM, Ellenville, NY Ian Pickus | News Director our UNDERWRITERS W271BF, 102.1 FM, Highland, NY Amber Sickles | Membership Director PAGE 11 W246BJ, 97.1 FM, Hudson, NY W204CJ, 88.7 FM, Lake Placid, NY W292DX, 106.3 FM, Middletown, NY WAMC-FM broadcasts 365 days a year W215BG, 90.9 FM, Milford, PA WAMC to eastern New York and western New W299AG, 107.7 FM, Newburgh, NY Box 66600 England on 90.3 MHz.