Endarterectomy Versus Stenting for Stroke Prevention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Having an Aortic Arch-Angiogram

Information for patients Having an Aortic Arch-Angiogram Sheffield Teaching Hospitals Other names: Aortic arch-angiogram, arch-angiogram, arch-aortogram. You have been given this leaflet because you need a procedure known as an Aortic Arch-Angiogram. This leaflet explains more about Aortic Arch-Angiograms, and answers some of the most frequently asked questions. If, after reading this leaflet, you have any questions or concerns, you should write them down and discuss them at your next appointment with the consultant, doctor or specialist nurse. It is important that you understand the procedure, along with the potential benefits and risks before you agree to it. Where will my hospital appointments take place? This will depend on which specialist doctor you are seen by. You could be seen by a Neurologist, a Stroke Physician, a Vascular Surgeon or a Radiologist. Most of the appointments will be at either the Northern General or Royal Hallamshire Hospitals. However, you may also be seen at one of the outreach clinics at Rotherham or Barnsley District Hospitals. 2 What is an aortic arch-angiogram? An aortic arch-angiogram is an x-ray test that enables us to diagnose a problem (most commonly a narrowing or a blockage) in the arteries supplying your head, neck and arms. Arteries do not usually show up on x-rays, so the images are obtained by introducing a long, thin, flexible tube (a catheter) into an artery, usually at the top of your leg. Then, a special x-ray dye (contrast medium) is injected through it, into the circulation. The blood flow carries the dye along, highlighting the arteries, and x-ray pictures are taken. -

Carotid Artery Stenting Initial Public Comments CAG-00085R June 18-July 18, 2004

Carotid Artery Stenting Initial Public Comments CAG-00085R June 18-July 18, 2004 Comment #1: Submitter: Peter Fail Organization: Cardiovascular Institute of the South Date: June 28, 2004 Comment: As an investigator of cartoid stenting in high risk patients, I feel that coverage of these patients will become a necesseity. The high risk patients not only has Carotid disease but usually a whole host of other vascular co- morbidiities that makes a surgical option "high risk". There are also those patients that the surgical option is non-existant due to anatomy weather a high or low lesions or because of prior radiation or surgery, etc. The proper training will difficult to access. Even those physicians in trial some of them have low numbers. (It is assumed that their numbers to get in to the trial was adequate). I am not sure what should be considered as an "adequate" number to be considered "trained". As the trials evolved the advent of embolic protection made the procedure "safer". There have been a number of times that I found debris in a filter and was thankful for it. The clinical event may not be that different with or without filters how ever I would argue that any debris in the brain is bad. It may not result in a clinically evident stroke, only a memory of a friend or something else that "can't" be tested for. I feel that using the current critera that were put forth as "high risk" by both SAPPHIRE and ARCHER some be atleast the baseline that can be used as a CAS requirement for "coverage". -

Investigating Signal Loss Due to a Carotid Artery Stent in 3D-TOF-MRA

Magn Reson Med Sci 2020; XX; XXX–XXX doi:10.2463/mrms.mp.2019-0083 Published Online: September 18, 2020 MAJOR PAPER Investigating Signal Loss due to a Carotid Artery Stent in 3D-TOF-MRA Hiroshi Kato*, Norio Ootani, Kentaro Abiru, and Mika Okahara Purpose: In this study, we investigated the factors of signal loss out because of the presence of a stent and optimized imaging parameters for improvement in depiction ability. Methods: We investigated the relationship between the stent type and magnetic susceptibility effect by mea- suring the signal value between the inside and outside of the stent with different Bw and TE for two different kinds of stents respectively. Similarly, flip angles were changed for two different kinds of stents respectively to the signal intensity between the inside and the outside of the stent was measured, in which examine the relationship between the stent type and the Ernst angles in RF-shielding effect. The conventional imaging parameters and the optimum imaging parameters for each stent obtained from the result of the phantom experiment were examined. Optimized 3D time-of-flight MR angiography (3D-TOF-MRA) was performed and compared with conventional 3D-TOF-MRA and computed tomography angiography (CTA). Results: The influence of the magnetic susceptibility effect is small in the central part of Carotid Wallstent and in PRECISE, and large in the Carotid Wallstent at the both ends. The influence of RF-shielding effect was large at PRECISE, where the Ernst angle was greatly shifted while the effect is no longer influenced at Carotid Wallstent. Both Carotid Wallstent and PRECISE made imaging capability improved by optimizing the imaging parameters. -

Carotid Endarterectomy Compared with Angioplasty and Stenting: the Status of the Debate

Neurosurg Focus 5 (6):Article 2, 1998 Carotid endarterectomy compared with angioplasty and stenting: the status of the debate Felipe C. Albuquerque, M.D., George P. Teitelbaum, M.D., Donald W. Larsen, M.D., and Steven L. Giannotta, M.D. Department of Neurological Surgery, Los Angeles County and University of Southern California Medical Center, Los Angeles, California Endarterectomy is the treatment of choice for patients with symptomatic stenosis of the internal carotid artery. Recently, debate has arisen over the potential benefits of endovascular techniques. Although retrospective analyses of angioplasty and stenting procedures suggest comparable clinical efficacy to endarterectomy, prospective evaluation is pending. The authors review the status of the debate and discuss those issues on both sides that are particularly contentious and clinically relevant. Key Words * carotid endarterectomy * angioplasty * stenting Atherosclerotic disease of the common carotid artery bifurcation is associated with 20 to 30% of cerebrovascular accidents.[13,15,27] Stroke is the third leading cause of death in the United States and the most common and disabling neurological disorder among the elderly worldwide.[13,15,27] In light of these public health concerns, research in the last half of this century has been focused on the optimum treatment of carotid artery stenosis. Prospective analyses such as those performed by the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET), the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study (ACAS), and the European Carotid Surgery Trial have demonstrated superior reduction in stroke incidence among symptomatic and a select group of asymptomatic patients who undergo carotid endarterectomy (CEA).[17,18,36] In fact, these studies have established CEA as the "gold standard" for the treatment of carotid artery atherosclerosis. -

Abbott Vascular Carotid Artery Stenting

Abbott Vascular Carotid Artery Stenting A Guide for Patients and Their Families AFM In Pg 1go Page 1 r Iob AreyStI 7P bott Vascular Carotid Artery Stenting A Guide for Patients and Their Families This guide provides you with information about carotid artery disease (narrowing of the neck arteries) and the treatment options. Endovascular treatment (procedures that are done through the blood vessels) using Abbott Vascular's RX Acculink Carotid Stent System or the XactTMCarotid Stent System, and the RX Accunet Embolic Protection System or the Emboshield NAV Embolic Protection System is one treatment option to reopen your narrowed neck arteries. Abbott Vascular's Carotid Stent Systems are authorized by Federal (U.S.) law for use in the treatment of carotid artery disease for patients who are ineligible for carotid surgery (endarterectomy) or at risk for surgical or anesthesia-related complications. This guide provides you with information about the RX Acculink and XactTM Carotid Stents and the procedure used to insert a stent into your carotid arteries. As you read, you might think of questions you would like to discuss with your doctor or nurse. You will find a place in the back of this guide for your questions and notes. Page 3 ble of Contents Carotid Artery Disease Your Brain What is Carotid Disease What are the Risk Factors for Carotid Artery Disease What are the Symptoms of Carotid Artery Disease What are the Symptoms of Stroke and TIA How Can my Doctor Tell if I Have Carotid Artery Disease Your Treatment Options Surgery Carotid Stenting Carotid Stent Procedure r ring For Your Procedure b/ire Your Procedure During Your Procedure Following Your Procedure Your Recovery Safety Information Benefits Contraindications Warnings Potential Complications Preventing Carotid Artery Disease Abbott Vascular Family of Carotid Clinical Studies Y^,r Stent Implant Card Lkuently Asked Questions Page 4 otid Artery Disease Your Brain Your brain is a very active organ. -

Multiple Supra-Aortic Stenting for Takayasu Arteritis: Extensive Revascularization and Two-Year Follow-Up

AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 23:790–793, May 2002 Case Report Multiple Supra-aortic Stenting for Takayasu Arteritis: Extensive Revascularization and Two-Year Follow-up Jun C. Takahashi, Nobuyuki Sakai, Hiroshi Manaka, Koji Iihara, Hideki Sakai, Hiroshi Sakaida, Toshio Higashi, Toshihiro Ishibashi, and Izumi Nagata Summary: A patient with Takayasu arteritis with multiple supra-aortic lesions underwent successful treatment with two-staged stent implantation. Stenotic bilateral common carotid, innominate, and left subclavian arteries were di- lated, and no restenosis was observed during the follow-up period of 2 years despite recurrent inflammation. Stenting for supra-aortic vessels in cases of Takayasu arteritis has rarely been reported, and to our knowledge, this is the first report of multiple stent placement for all the supra-aortic branches involved. Takayasu arteritis, an inflammatory disease of un- known origin, frequently affects major supra-aortic vessels and causes many symptoms, including brain and retinal ischemia (1). During the last decade, per- cutaneous transluminal angioplasty has been re- ported to be effective for releasing the stenotic le- sions in this disease; however, the rate of restenosis has been found to be much higher than that associ- ated with atherosclerotic lesions (2, 3). Recently, stent placement has emerged as a reasonable alter- FIG 1. Angiogram obtained 1 year before admission. Stenosis native for the treatment of vascular stenosis, but its of the bilateral common carotid and subclavian arteries is noted. effectiveness in inflammatory lesions is still not clear, especially in carotid artery lesions. We herein report right eye, indicating chronic retinal ischemia. Serum C-reactive the case of two-staged stent implantation in a patient protein was within normal limits, and MR imaging showed no with Takayasu arteritis that involved all the major cerebral infarction. -

When Is Carotid Angioplasty and Stenting the Cost-Effective Alternative for Revascularization of Symptomatic Carotid Stenosis? a Canadian Health System Perspective

ORIGINAL RESEARCH INTERVENTIONAL When Is Carotid Angioplasty and Stenting the Cost-Effective Alternative for Revascularization of Symptomatic Carotid Stenosis? A Canadian Health System Perspective M.A. Almekhlafi, M.D. Hill, S. Wiebe, M. Goyal, D. Yavin, J.H. Wong, and F.M. Clement EBM 1 ABSTRACT BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Carotid revascularization procedures can be complicated by stroke. Additional disability adds to the already high costs of the procedure. To weigh the cost and benefit, we estimated the cost-utility of carotid angioplasty and stenting compared with carotid endarterectomy among patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis, with special emphasis on scenario analyses that would yield carotid angioplasty and stenting as the cost-effective alternative relative to carotid endarterectomy. MATERIALS AND METHODS: A cost-utility analysis from the perspective of the health system payer was performed by using a Markov analytic model. Clinical estimates were based on a meta-analysis. The procedural costs were derived from a microcosting data base. The costs for hospitalization and rehabilitation of patients with stroke were based on a Canadian multicenter study. Utilities were based on a randomized controlled trial. RESULTS: In the base case analysis, carotid angioplasty and stenting were more expensive (incremental cost of $6107) and had a lower utility (Ϫ0.12 quality-adjusted life years) than carotid endarterectomy. The results are sensitive to changes in the risk of clinical events and the relative risk of death and stroke. Carotid angioplasty and stenting were more economically attractive among high-risk surgical patients. For carotid angioplasty and stenting to become the preferred option, their costs would need to fall from more than $7300 to $4350 or less and the risks of the periprocedural and annual minor strokes would have to be equivalent to that of carotid endarterectomy. -

MMVR 13 Organizing Committee

MMVR 13 Organizing Committee Michael J. Ackerman PhD * Roger Phillips PhD CEng MBCS * High Performance Computing & Communications, Dept of Computer Science, National Library of Medicine University of Hull (UK) Ian Alger MD Richard A. Robb PhD * New York Presbyterian Hospital; Mayo Biomedical Imaging Resource, Weill Medical College of Cornell University Mayo Clinic College of Medicine David C. Balch MA Jannick P. Rolland PhD DCB Consulting LLC ODA Lab, School of Optics / CREOL, University of Central Florida Steve Charles MD * MicroDexterity Systems; Ajit K. Sachdeva MD FRCSC FACS University of Tennessee Division of Education, American College of Surgeons Patrick C. Cregan FRACS * Nepean Hospital, Richard M. Satava MD FACS * Wentworth Area Health Service Dept of Surgery, University of Washington; DARPA; TATRC/USAMRMC Henry Fuchs PhD Dept of Computer Science, Rainer M.M. Seibel MD University of North Carolina Diagnostic & Interventional Radiology, University of Witten/Herdecke Walter J. Greenleaf PhD * Greenleaf Medical Systems Steven Senger PhD * Dept of Computer Science, Randy S. Haluck MD FACS * University of Wisconsin - La Crosse Dept of Surgery, Penn State College of Medicine Ramin Shahidi PhD * Image Guidance Laboratories, David M. Hananel * Stanford University School of Medicine Surgical Programs, Medical Education Technologies Inc. Faina Shtern MD Beth Israel Deaconess; Children's Medical Center; Wm. LeRoy Heinrichs MD PhD Harvard Medical School Medical Media & Information Technologies/ Gynecology & Obstetrics, Don Stredney Stanford University School of Medicine Interface Laboratory, OSC Helene M. Hoffman PhD * School of Medicine, Julie A. Swain MD * University of California, San Diego Cardiovascular and Respiratory Devices, U.S. Food and Drug Administration Heinz U. Lemke PhD Institute for Technical Informatics, Kirby G. -

Preliminary Programme

PRELIMINARY PROGRAMME ECR 2017 will be a green meeting designed to meet environmental sustainability criteria set by the Österreichisches Umweltzeichen (Austria’s national eco-friendly certificate). The ECR is the annual meeting of the European Society of Radiology (ESR). Thanks to the collaboration with the European Federation of Radiographer Societies (EFRS), the ECR can also be considered the annual meeting of radiographers in Europe. COORDINATION European Society of Radiology ESR Office, Neutorgasse 9, 1010 Vienna, Austria Phone: (+ 43 1) 533 40 64-0 E-mail: [email protected] www.myESR.org Managing Editor: Julia Patuzzi Coordination of the scientific programme: ECR Scientific Programme Department Art Direction: Ronald Talasz Layout: Barbara Biegl Photo Credits: Unless otherwise indicated all pictures © ESR – European Society of Radiology TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION ECR 2017 Timeline .................................5 ESR Executive Council .............................92 Registration Information ............................7 ECR 2017 Congress Committees ....................93 Timetable .........................................8 ECR 2017 Topic Coordinators .......................97 Interview with the ESR President ...................10 ESR Dignitaries ...................................16 SCIENTIFIC PROGRAMME Headline Sessions .................................14 Refresher Courses .................................61 ESR/EFRS meets Sessions .........................17 Abdominal and Gastrointestinal .................62 New -

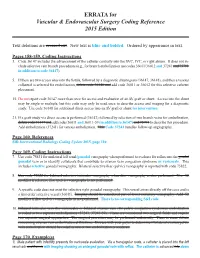

ERRATA for Vascular & Endovascular Surgery Coding Reference 2015

ERRATA for Vascular & Endovascular Surgery Coding Reference 2015 Edition Text deletions are crossed out. New text is blue and bolded. Ordered by appearance in text. Pages 158-159, Coding Instructions 3. Code 36147 includes the advancement of the catheter centrally into the SVC, IVC, or right atrium. It does not in- clude selective vein branch procedures (e.g., for branch embolization use codes 36011/36012 and 37241 and 75791 in addition to code 36147). 5. If there are two access sites into the fistula, followed by a diagnostic shuntogram (36147, 36148), and then a venous collateral is selected for embolization, delete code 36148 and add code 36011 or 36012 for this selective catheter placement. 15. Do not report code 36147 more than once for access and evaluation of an AV graft or shunt. Access into the shunt may be single or multiple, but this code may only be used once to describe access and imaging for a diagnostic study. Use code 36148 for additional direct access into an AV graft or shunt for intervention. 21. If a graft study via direct access is performed (36147) followed by selection of two branch veins for embolization, delete code 36147 and add codes 36011 and 36011-59 (in addition to 36147) and 75791 to describe this procedure. Add embolization (37241) for venous embolization. This Code 37241 bundles follow-up angiography. Page 160, References SIR Interventional Radiology Coding Update 2015, page 110 Page 169, Coding Instructions 7. Use code 75831 for unilateral left renal/gonadal venography when performed to evaluate for reflux into thegondal gonadal vein or to identify collaterals that contribute to ovarian vein congestion syndrome or varicocele. -

2010 Abstracts

1 Carotid Stenting is inferior to Carotid Endarterectomy in the Low Physiologic Risk population: Results of the National Inpatient Sample, 2004-7 John S. Lane, III, MD, Cheryl P. Magno, Andrew R. Barleben, Karen T. Lane, Ninh T. Nguyen and Roy M. Fujitani, MD Vascular Surgery, UC Irvine, Orange, CA and Orange, CA Objective: The SAPPHIRE trial established that Carotid Artery Stenting (CAS) is not inferior to Carotid Endarterectomy (CEA) for high surgical risk patients. The CREST trial has shown CEA have a lower stroke rate than CAS, at the expense of higher cardiac complications. The objective of this study is to evaluate the nationwide performance of CAS and CEA in both high (HR) and low physiologic risk (LR) patients, outside of the clinical trial setting. Methods: Data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) was pooled for patients undergoing carotid intervention from 2004-7. HR was defined as pre-existing cardiac disease (CHF, valvular disease), or COPD. Stroke, death, myocardial infarction and complication rates were determined in both HR and LR populations. Multivariate regression analysis was performed to determine adjusted odds of stroke and death. Results: From 2004-7, CEA was performed in 490,665 patients (HR 30.6%) and CAS in 50,283 patients (HR 31.2%). Unadjusted stroke/death rates were higher for CAS vs CEA in both HR and LR groups (table). Myocardial infarction rates were equivalent in the HR population and slightly higher for CAS in LR population. Combined complication rates were higher after CEA vs CAS, mainly due to pulmonary and renal complications. Multivariate regression analysis revealed adjusted odds of stroke/death were increased for CAS (OR 1.36, CI 1.28-1.45). -

Carotid Stenting – Dos and Don’Ts

Step by step: Carotid stenting – Dos and Don’ts Gianmarco de Donato Vascular and Endovascular Surgery Unit University of Siena Siena - Italy Vascular and Endovascular Surgery Unit - University of Siena Tips & tricks Carotid artery stenting is an advanced endovascular procedure… …. but some rules on dos and don’ts can make it easer Vascular and Endovascular Surgery Unit - University of Siena Carotid stenting The entire CAS team should have: 1. in-depth knowledge of the carotid pathology 2. in-depth knowledge of the materials 3. in-depth knowledge of techniques to apply in given situations. Vascular and Endovascular Surgery Unit - University of Siena Carotid Artery Stenting Step-by-step • Clinical protocol • CAS technique – Vascular access – Angiographic evaluation – Common carotid engagement – Crossing the stenosis – EPD management – Pre-dilatation – Stent selection and deployment – Post-dilatation • Final angiographic evaluation Vascular and Endovascular Surgery Unit - University of Siena ClinicalClinical protocolprotocol Pre meds ASA 100 mg PO Clopiogrel 75 mg/die, or Ticagrerol 180 mg/die Double anti-platelet aggregation 1 month days - 5 t 0: procedure Vascular and Endovascular Surgery Unit - University of Siena ClinicalClinical protocol protocol Pre procedure Echo-Doppler, CT / MRI Independent neuro evaluation Procedure consent signed Vascular and Endovascular Surgery Unit - University of Siena ClinicalClinical protocol protocol To operate on patients without - double antiplatelet therapy (full regimen) - anatomical evaluation of epiaortic