Costa Rica: Review of the Financial System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1935 Time Capsule Part 3

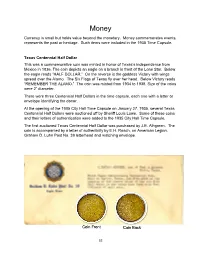

Money Currency is small but holds value beyond the monetary. Money commemorates events, represents the past or heritage. Such items were included in the 1935 Time Capsule. Texas Centennial Half Dollar This was a commemorative coin was minted in honor of Texas’s independence from Mexico in 1836. The coin depicts an eagle on a branch in front of the Lone Star. Below the eagle reads “HALF DOLLAR.” On the reverse is the goddess Victory with wings spread over the Alamo. The Six Flags of Texas fly over her head. Below Victory reads “REMEMBER THE ALAMO.” The coin was minted from 1934 to 1938. Size of the coins were 2” diameter. There were three Centennial Half Dollars in the time capsule, each one with a letter or envelope identifying the donor. At the opening of the 1905 City Hall Time Capsule on January 27, 1935, several Texas Centennial Half Dollars were auctioned off by Sheriff Louis Lowe. Some of these coins and their letters of authentication were added to the 1935 City Hall Time Capsule. The first auctioned Texas Centennial Half Dollar was purchased by J.E. Alhgreen. The coin is accompanied by a letter of authenticity by E.H. Roach, on American Legion, Graham D. Luhn Post No. 39 letterhead and matching envelope. Coin Front Coin Back 32 Letter Front 33 Letter Back 34 The second Texas Centennial Half Dollar was purchased at the same auction by E.E. Rummel. Shown below are the paperwork establishing the authenticity of the purchase by E.H. Roach, on American Legion, Graham D. -

Corporate Presentation 2020 Disclaimer

Corporate Presentation 2020 Disclaimer Grupo Aval Acciones y Valores S.A. (“Grupo Aval”) is an issuer of securities in Colombia and in the United States.. As such, it is subject to compliance with securities regulation in Colombia and applicable U.S. securities regulation. Grupo Aval is also subject to the inspection and supervision of the Superintendency of Finance as holding company of the Aval financial conglomerate. The consolidated financial information included in this document is presented in accordance with IFRS as currently issued by the IASB. Details of the calculations of non-GAAP measures such as ROAA and ROAE, among others, are explained when required in this report. This report includes forward-looking statements. In some cases, you can identify these forward-looking statements by words such as “may,” “will,” “should,” “expects,” “plans,” “anticipates,” “believes,” “estimates,” “predicts,” “potential,” or “continue,” or the negative of these and other comparable words. Actual results and events may differ materially from those anticipated herein as a consequence of changes in general, economic and business conditions, changes in interest and currency rates and other risk described from time to time in our filings with the Registro Nacional de Valores y Emisores and the SEC. Recipients of this document are responsible for the assessment and use of the information provided herein. Matters described in this presentation and our knowledge of them may change extensively and materially over time but we expressly disclaim any obligation to review, update or correct the information provided in this report, including any forward looking statements, and do not intend to provide any update for such material developments prior to our next earnings report. -

BAC International Bank Inc

BAC International Bank Inc. Primary Credit Analyst: Fernando Staines, Mexico City 52 (55) 50814411; [email protected] Secondary Contact: Jesus Sotomayor, Mexico City (52) 55-5081-4486; [email protected] Table Of Contents Major Rating Factors Outlook Rationale Related Criteria WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT NOVEMBER 4, 2020 1 BAC International Bank Inc. Additional SACP bbb- Support 0 -1 + + Factors Anchor bb+ Issuer Credit Rating ALAC 0 Business Support Strong Position +1 Capital and GRE Support Moderate 0 Earnings 0 Risk Position Adequate 0 Group BB+/Stable/B Support 0 Funding Average 0 Sovereign Liquidity Adequate Support 0 Major Rating Factors Strengths: Weaknesses: • BAC International Bank Inc.'s (BIB) main strengths • Recent economic struggles related to the COVID-19 stem from its funding structure that leans on a stable pandemic, coupled with the historical political and pulverized deposit base with manageable vulnerability within the region could represent a short-term financial obligations. challenge for the bank's profitability and asset • Lead player in consumer lending and the largest quality metrics. financial conglomerate in Central America; and • Large exposure to consumer segment could • Highly diversified by geography, economic sector, represent additional pressures on asset quality and client, allowing us to rate the bank above the metrics during the pandemic. sovereign rating on Costa Rica (B+/Negative/B), to • Our current moderate capital and earnings which it is highly exposed. assessment incorporates the region's high economic risks. WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT NOVEMBER 4, 2020 2 BAC International Bank Inc. Outlook: Stable The stable outlook on BIB continues to reflect that on the parent Banco de Bogotá (BdeB; BB+/Stable/B). -

Elimination of the One Cent Coin the Bahamian One Cent Coin Or the “Penny” Is Being Phased

Central Bank of The Bahamas FAQS: Elimination of the One Cent Coin The Bahamian one cent coin or the “penny” is being phased out of circulation. After the end of 2020 it will no longer be legal tender in The Bahamas. It is further proposed that circulation of or acceptance of US pennies will cease at the same time as the Bahamian coin. Why is the one cent coin or penny being phased out? Rising cost of production relative to face value Increased accumulation and non-use of pennies The significant handling cost of pennies When will the Central Bank stop distributing the penny? The Central Bank will stop distributing pennies to commercial banks on the 31st January 2020. Financial institutions will no longer be providing new supplies of the coins to consumers and businesses. Are businesses required to accept pennies after the end of January 2020? NO. Businesses may decide to stop accepting pennies anytime after the end of January 2020. Can businesses continue to accept pennies after the end of December 2020? NO. Businesses will not be able to accept payment or give change in one cent pieces after the end of December 2020. All cash payments will to be rounded to the nearest five cents. How will cash amounts be rounded? Business must round the total amount due to the nearest five cents If your total bill is $9.42 or $9.41. The nearest five cents to either of these would be $9.40 If your total bill is $9.43 or $9.44, the nearest five cents to either of these would be $9.45. -

A History of the Canadian Dollar 53 Royal Bank of Canada, $5, 1943 in 1944, Banks Were Prohibited from Issuing Their Own Notes

Canada under Fixed Exchange Rates and Exchange Controls (1939-50) Bank of Canada, $2, 1937 The 1937 issue differed considerably in design from its 1935 counterpart. The portrait of King George VI appeared in the centre of all but two denominations. The colour of the $2 note in this issue was changed to terra cotta from blue to avoid confusion with the green $1 notes. This was the Bank’s first issue to include French and English text on the same note. The war years (1939-45) and foreign exchange reserves. The Board was responsible to the minister of finance, and its Exchange controls were introduced in chairman was the Governor of the Bank of Canada through an Order-in-Council passed on Canada. Day-to-day operations of the FECB were 15 September 1939 and took effect the following carried out mainly by Bank of Canada staff. day, under the authority of the War Measures Act.70 The Foreign Exchange Control Order established a The Foreign Exchange Control Order legal framework for the control of foreign authorized the FECB to fix, subject to ministerial exchange transactions, and the Foreign Exchange approval, the exchange rate of the Canadian dollar Control Board (FECB) began operations on vis-à-vis the U.S. dollar and the pound sterling. 16 September.71 The Exchange Fund Account was Accordingly, the FECB fixed the Canadian-dollar activated at the same time to hold Canada’s gold value of the U.S. dollar at Can$1.10 (US$0.9091) 70. Parliament did not, in fact, have an opportunity to vote on exchange controls until after the war. -

INCAE Identity

04 INCAE Identity 06 Message from the President 08 Change Agents INDEX 20 Our Faculty 24 Academic Alliances 28 Corporate Partners 38 INCAE’s Global Reach 42 50th Anniversary 52 Our Impact 56 Far-Reaching Initiatives Accounts 70 Governance Structure INCAE IDENTITY INCAE INCAE IDENTITY IDENTITY 4 5 50 years making history INCAE Business School, Today, INCAE focuses on three key ac- • Research, teaching, and the use of founded in 1964, was an tivities modern management concepts and te- chniques. initiative launched by the • Masters programs in areas key to La- • Strengthening analytical skills, and governments and business tin American development. mastery of complex economic, political community of Central America. • Executive Education programs and and social phenomena. seminars. The initiative received support • Facilitating dialogue, understanding, from the President of the • Research projects that foster compe- and collaboration between individuals, titiveness in the region, whose applied United States, John F. Kennedy, different sectors and nations. focus combines best practices and and advisors from the Harvard global knowledge with the reality of the Business School, in a process Latin American context. led by Harvard Business School VISION professor George Cabot Lodge Our goal for the next 50 years is to con- and Central American MISSION tinue to be recognised as a world-class businessman Francisco de Sola. business school, and the best in Latin For 50 years, INCAE Business School America: a leader in business adminis- has actively -

Memoria Anual 2016 Memoria Anual 2016 2 Memoria Anual 2016 | BAC|Credomatic Contenido

Memoria Anual 2016 Memoria Anual 2016 2 Memoria Anual 2016 | BAC|Credomatic Contenido Mensaje del Presidente 3 Historia 4 Resumen de las principales cifras 2016 6 BAC|Credomatic en un vistazo 8 Junta Directiva BAC International Bank, Inc. 10 Estructura de Gestión 11 Nuestra Organización en cifras 13 Entorno Económico y Sistema Bancario en Centroamérica 21 Crecimiento con innovación 31 Control Operativo 41 Control del Riesgo 45 Canales digitales 57 Compromiso organizacional y sostenibilidad 63 Memoria Anual 2016 | BAC|Credomatic 3 Mensaje del Presidente Estimados Clientes, Accionistas y Colaboradores: El Grupo siempre se ha caracterizado en ser pionero en el uso de la tecnología, este año hemos continuado con Somos un banco regional que opera con una presencia este proceso aprovechando las nuevas herramientas relevante en toda Centroamérica (incluyendo Panamá), para facilitar la vida de nuestros clientes, por ejemplo, lo cual nos da grandes ventajas en términos de diver- en nuestra Sucursal Electrónica ahora se pueden realizar sificación y escala, además de que nos permite ofrecer gran cantidad de gestiones sin tener que desplazarse a mejores herramientas a nuestros clientes que operan en nuestras sucursales físicas. Cada vez estamos más cerca esta región en la que creemos y apoyamos en su desa- de nuestros clientes que ya pueden realizar transaccio- rrollo. nes y gestiones a través de nuestras aplicaciones móvi- les siempre con los más altos estándares de seguridad. Facilitamos el intercambio de bienes y servicios y favore- cemos la canalización del crédito y el ahorro. Este 2017 se nos presenta como un año de cambios re- levantes para la organización, nuestras estructuras ad- Además de los ingresos que generamos, una porción im- ministrativas han variado sus liderazgos en Costa Rica, portante los pagamos a nuestros proveedores por bie- Guatemala y Panamá, bajo un proceso maduro y plani- nes y servicios. -

E Euro Symbol Was Created by the European Commission

e eu ro c o i n s 1 unity an d d i v e r s i t The euro, our currency y A symbol for the European currency e euro symbol was created by the European Commission. e design had to satisfy three simple criteria: ADF and BCDE • to be a highly recognisable symbol of Europe, intersect at D • to have a visual link with existing well-known currency symbols, and • to be aesthetically pleasing and easy to write by hand. Some thirty drafts were drawn up internally. Of these, ten were put to the test of approval by the BCDE, DH and IJ general public. Two designs emerged from the are parallel scale survey well ahead of the rest. It was from these two BCDE intersects that the President of the Commission at the time, at C Jacques Santer, and the European Commissioner with responsibility for the euro, Yves-ibault de Silguy, Euro symbol: geometric construction made their final choice. Jacques Santer and Yves-ibault de Silguy e final choice, the symbol €, was inspired by the letter epsilon, harking back to classical times and the cradle of European civilisation. e symbol also refers to the first letter of the word “Europe”. e two parallel lines indicate the stability of the euro, as they do in the symbol of the dollar and the yen. e official abbreviation for the euro is EUR. © European Communities, 2008 e eu ro c o i n s 2 unity an d d i v e r s i t The euro, our currency y Two sides of a coin – designing the European side e euro coins are produced by the euro area countries themselves, unlike the banknotes which are printed by the ECB. -

Bac Guatemala

CASE STUDY Bac Guatemala v.e.0221 CASE STUDY • CUSTOMER BAC • INDUSTRY GUATEMALA Banking BAC Credomatic is present in six countries: Panama, Costa • LOCATION Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala. With a Guatemala wide geographic presence, the group has also been able to • SOLUTION increase its client base. It currently serves more than 2.2 million Improving the banking customer people and more than 100,000 companies. In Guatemala it experience through queue occupies the first place in profits. management - www .acf t e chnolog i e s . c o m THE CHALLENGE BAC Credomatic is focused on moving forward with a digitalization pro- cess in order to respond more efficiently to the needs of its customers. The group has launched several processes in order to be more efficient, increa- se specialization, allow faster response times and maintain a leading posi- tion in technological advances with digital platforms that improve the user experience and offer greater security, as well as comfort. By May 2017, they were testing a demonstration pilot of Q-Flow in their offices to ensure that Q-Flow worked as expected. Then, in June 2017, when the bank acquired another 13 branches, they decided to start using a new business model to improve the customer experience: a self-mana- ged process that would give them a unique and differentiated experience for their clients, like no other. It is based on an innovative, modern, customer-centered design. THE SOLUTION In ten days, ACF Technologies was able to install a fully functional Q-Flow solution in the BAC Credomatic technology area. -

Corporate Presentation September 2019 Disclaimer

Corporate Presentation September 2019 Disclaimer Grupo Aval Acciones y Valores S.A. (“Grupo Aval”) is an issuer of securities in Colombia and in the United States, registered with Colombia’s National Registry of Shares and Issuers (Registro Nacional de Valores y Emisores) and the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”). As such, it is subject to compliance with securities regulation in Colombia and applicable U.S. securities regulation. All of our banking subsidiaries (Banco de Bogotá, Banco de Occidente, Banco Popular and Banco AV Villas), Porvenir and Corficolombiana, are subject to inspection and supervision as financial institutions by the Superintendency of Finance. Grupo Aval is now also subject to the inspection and supervision of the Superintendency of Finance as a result of Law 1870 of 2017, also known as Law of Financial Conglomerates, which came in effect on February 6, 2019. Grupo Aval, as the holding company of its financial conglomerate is responsible for the compliance with capital adequacy requirements, corporate governance standards, risk management and internal control and criteria for identifying, managing and revealing conflicts of interest, applicable to its financial conglomerate. The consolidated financial information included in this document is presented in accordance with IFRS as currently issued by the IASB. Details of the calculations of non-GAAP measures such as ROAA and ROAE, among others, are explained when required in this report. Grupo Aval has adopted IFRS 16 retrospectively from January 1, 2019 but has not restated comparatives for the 2018 reporting period, as permitted under the specific transitional provisions in the standard. The reclassifications and the adjustments arising from the new leasing rules are therefore recognized in the opening Condensed Consolidated Statement of Financial Position on January 1, 2019. -

Memoria Anual 2012

MEMORIA ANUAL 2012 MEMORIA ANUAL 2012 MEMORIA 2012 2 ÍNDICE IDENTIDAD INCAE ................................................................................................................... 5 MENSAJE DEL RECTOR .......................................................................................................... 7 AGENTES DE CAMBIO ............................................................................................................ 9 DESDE LA FACULTAD.............................................................................................................. 16 ALIANZAS ESTRATÉGICAS...................................................................................................... 19 SOCIOS CORPORATIVOS.......................................................................................................... 21 INCAE CON PRESENCIA GLOBAL............................................................................................ 25 NUESTRO IMPACTO ................................................................................................................ 28 INICIATIVAS TRASCENDENTALES........................................................................................... 30 RENDICIÓN DE CUENTAS........................................................................................................ 40 CUERPO DE GOBIERNO............................................................................................................ 55 CONTÁCTENOS........................................................................................................................ -

Financial Statements Of

BAC BAHAMAS BANK LIMITED Financial Statements Year ended December 31, 2019 Page Independent Auditors’ Report 1 - 2 Statement of Financial Position 3 Statement of Comprehensive Income 4 Statement of Changes in Equity 5 Statement of Cash Flows 6 Notes to Financial Statements 7 - 47 BAC BAHAMAS BANK LIMITED Statement of Comprehensive Income Year ended December 31, 2019, with corresponding figures for 2018 (Expressed in United States dollars) 2019 2018 Net interest income: Interest income calculated using the effective interest method on cash and cash equivalents (note 7) $ 2,694,218 2,870,986 Interest income calculated using the effective interest method on loans to customers (note 7) 119,562 173,354 Interest income on investments 374,250 0 Interest expense (note 7) (958,710) (796,871) Net interest income 2,229,320 2,247,469 Net commission income: Commission income 11,172 16,263 Commission expense (29,162) (18,945) Net commision expense (17,990) (2,682) Other operating (expense) income: Other income (note 7) 35,123 39,201 General and administrative expenses (notes 7 and 15) (699,668) (877,817) Reversal of impairment losses on loan (note 5) 25,328 20,434 (639,217) (818,182) Net income 1,572,113 1,426,605 Other comprehensive income: Net change in fair value of investments 7,389 0 Net income and total comprehensive income for the year $ 1,579,502 1,426,605 The accompanying notes are an integral part of these financial statements. 4 BAC BAHAMAS BANK LIMITED Statement of Changes in Equity Year ended December 31, 2019, with corresponding figures