The Progressive Age of Globalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Parliament Elections 2019 - Forecast

Briefing May 2019 European Parliament Elections 2019 - Forecast Austria – 18 MEPs Staff lead: Nick Dornheim PARTIES (EP group) Freedom Party of Austria The Greens – The Green Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) (EPP) Social Democratic Party of Austria NEOS – The New (FPÖ) (Salvini’s Alliance) – Alternative (Greens/EFA) – 6 seats (SPÖ) (S&D) - 5 seats Austria (ALDE) 1 seat 5 seats 1 seat 1. Othmar Karas* Andreas Schieder Harald Vilimsky* Werner Kogler Claudia Gamon 2. Karoline Edtstadler Evelyn Regner* Georg Mayer* Sarah Wiener Karin Feldinger 3. Angelika Winzig Günther Sidl Petra Steger Monika Vana* Stefan Windberger 4. Simone Schmiedtbauer Bettina Vollath Roman Haider Thomas Waitz* Stefan Zotti 5. Lukas Mandl* Hannes Heide Vesna Schuster Olga Voglauer Nini Tsiklauri 6. Wolfram Pirchner Julia Elisabeth Herr Elisabeth Dieringer-Granza Thomas Schobesberger Johannes Margreiter 7. Christian Sagartz Christian Alexander Dax Josef Graf Teresa Reiter 8. Barbara Thaler Stefanie Mösl Maximilian Kurz Isak Schneider 9. Christian Zoll Luca Peter Marco Kaiser Andrea Kerbleder Peter Berry 10. Claudia Wolf-Schöffmann Theresa Muigg Karin Berger Julia Reichenhauser NB 1: Only the parties reaching the 4% electoral threshold are mentioned in the table. Likely to be elected Unlikely to be elected or *: Incumbent Member of the NB 2: 18 seats are allocated to Austria, same as in the previous election. and/or take seat to take seat, if elected European Parliament ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• www.eurocommerce.eu Belgium – 21 MEPs Staff lead: Stefania Moise PARTIES (EP group) DUTCH SPEAKING CONSITUENCY FRENCH SPEAKING CONSITUENCY GERMAN SPEAKING CONSTITUENCY 1. Geert Bourgeois 1. Paul Magnette 1. Pascal Arimont* 2. Assita Kanko 2. Maria Arena* 2. -

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2

1. Debbie Abrahams, Labour Party, United Kingdom 2. Malik Ben Achour, PS, Belgium 3. Tina Acketoft, Liberal Party, Sweden 4. Senator Fatima Ahallouch, PS, Belgium 5. Lord Nazir Ahmed, Non-affiliated, United Kingdom 6. Senator Alberto Airola, M5S, Italy 7. Hussein al-Taee, Social Democratic Party, Finland 8. Éric Alauzet, La République en Marche, France 9. Patricia Blanquer Alcaraz, Socialist Party, Spain 10. Lord John Alderdice, Liberal Democrats, United Kingdom 11. Felipe Jesús Sicilia Alférez, Socialist Party, Spain 12. Senator Alessandro Alfieri, PD, Italy 13. François Alfonsi, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (France) 14. Amira Mohamed Ali, Chairperson of the Parliamentary Group, Die Linke, Germany 15. Rushanara Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 16. Tahir Ali, Labour Party, United Kingdom 17. Mahir Alkaya, Spokesperson for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation, Socialist Party, the Netherlands 18. Senator Josefina Bueno Alonso, Socialist Party, Spain 19. Lord David Alton of Liverpool, Crossbench, United Kingdom 20. Patxi López Álvarez, Socialist Party, Spain 21. Nacho Sánchez Amor, S&D, European Parliament (Spain) 22. Luise Amtsberg, Green Party, Germany 23. Senator Bert Anciaux, sp.a, Belgium 24. Rt Hon Michael Ancram, the Marquess of Lothian, Former Chairman of the Conservative Party, Conservative Party, United Kingdom 25. Karin Andersen, Socialist Left Party, Norway 26. Kirsten Normann Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 27. Theresa Berg Andersen, Socialist People’s Party (SF), Denmark 28. Rasmus Andresen, Greens/EFA, European Parliament (Germany) 29. Lord David Anderson of Ipswich QC, Crossbench, United Kingdom 30. Barry Andrews, Renew Europe, European Parliament (Ireland) 31. Chris Andrews, Sinn Féin, Ireland 32. Eric Andrieu, S&D, European Parliament (France) 33. -

Green Recovery Call to Action & Signatories 121

GREENRECOVERY REBOOT & REBOOST our economies for a sustainable future Call for mobilisation The coronavirus crisis is shaking the whole world, with devastating consequences across Europe. We are being put to the test. We are suffering and mourning our losses, and this crisis is testing the limits of our system. It is also a test of our great European solidarity and of our institutions, which acted fast at the start of the crisis to deploy measures to protect us. The crisis is still ongoing, but we will see the light at the end of the tunnel, and by fighting together, we will beat the virus. Never have we faced such a challenging situation in peacetime. The fight against the pandemic is our top priority and everything that is needed to stop it and eradicate the virus must be done. We welcome and strongly support all the actions developed by governments, EU institutions, local authorities, scientists, medical staff, volunteers, citizens and economic actors. In this tremendously difficult situation, we are also facing another crisis: a shock to our economy tougher than the 2008 crisis. The major shock to the economy and workers created by the pandemic calls for a strong coordinated economic response. We therefore welcome the declaration of European leaders stating that they will do “whatever it takes” to tackle the social and economic consequences of this crisis. However, what worked for the 2008 financial crisis may not be sufficient to overcome this one. The economic recovery will only come with massive investments to protect and create jobs and to support all the companies, regions and sectors that have suffered from the economy coming to a sudden halt. -

Lettre Conjointe De 1.080 Parlementaires De 25 Pays Européens Aux Gouvernements Et Dirigeants Européens Contre L'annexion De La Cisjordanie Par Israël

Lettre conjointe de 1.080 parlementaires de 25 pays européens aux gouvernements et dirigeants européens contre l'annexion de la Cisjordanie par Israël 23 juin 2020 Nous, parlementaires de toute l'Europe engagés en faveur d'un ordre mondial fonde ́ sur le droit international, partageons de vives inquietudeś concernant le plan du president́ Trump pour le conflit israeló -palestinien et la perspective d'une annexion israélienne du territoire de la Cisjordanie. Nous sommes profondement́ preoccuṕ eś par le preć edent́ que cela creerait́ pour les relations internationales en geń eral.́ Depuis des decennies,́ l'Europe promeut une solution juste au conflit israeló -palestinien sous la forme d'une solution a ̀ deux Etats,́ conformement́ au droit international et aux resolutionś pertinentes du Conseil de securit́ e ́ des Nations unies. Malheureusement, le plan du president́ Trump s'ecarté des parametres̀ et des principes convenus au niveau international. Il favorise un controlê israelień permanent sur un territoire palestinien fragmente,́ laissant les Palestiniens sans souverainete ́ et donnant feu vert a ̀ Israel̈ pour annexer unilateralement́ des parties importantes de la Cisjordanie. Suivant la voie du plan Trump, la coalition israelienné recemment́ composeé stipule que le gouvernement peut aller de l'avant avec l'annexion des̀ le 1er juillet 2020. Cette decisioń sera fatale aux perspectives de paix israeló -palestinienne et remettra en question les normes les plus fondamentales qui guident les relations internationales, y compris la Charte des Nations unies. Nous sommes profondement́ preoccuṕ eś par l'impact de l'annexion sur la vie des Israelienś et des Palestiniens ainsi que par son potentiel destabilisateuŕ dans la regioń aux portes de notre continent. -

European Alliance for a Green Recovery

Launch of the European alliance for a Green Recovery Press Release Under embargo until 14/04 7:00am At the initiative of Pascal Canfin, Chair of the Environment Committee at the European Parliament, 180 political decision-makers, business leaders, trade unions, NGOs, and think tanks have come together to form a European alliance for a Green Recovery. In the face of the coronavirus crisis, the biggest challenge Europe has faced in peacetime, with devastating consequences and a shock to the economy tougher than the 2008 crisis, Ministers from 11 countries, 79 cross-party MEPs from 17 Member States, 37 CEOs, 28 business associations representing 10 different sectors, trade union confederation representing members from 90 national trade union organisations and 10 trade union federations, 7 NGOs and 6 think tanks, have committed to working together to create, support and implement solutions to prepare our economies for the world of tomorrow. This first pan-European call for mobilisation on post-crisis green investment packages will work to build the recovery and transformation plans which enshrine the fight against climate change and biodiversity as a key pillar of the economic strategy. Sharing the belief that the economic recovery will only come with massive investments to protect and create jobs and to support all companies, regions and sectors that have suffered from the economy coming to a sudden halt, the alliance commits to contribute to the post-crisis investment decisions needed to reboot and reboost our economy. Covid-19 will not make climate change and nature degradation go away. The fight against this crisis will not be won without a solid economic response. -

A Look at the New European Parliament Page 1 INTERNATIONAL TRADE COMMITTEE (INTA)

THE NEW EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT KEY COMMITTEE COMPOSITION 31 JULY 2019 INTRODUCTION After several marathon sessions, the European Council agreed on the line-up for the EU “top jobs” on 2 July 2019. The deal, which notably saw German Defence Minister Ursula von der Leyen (CDU, EPP) surprisingly designated as the next European Commission (EC) President, meant that the European Parliament (EP) could proceed with the election of its own leadership on 3 July. The EPP and Renew Europe (formerly ALDE) groups, in line with the agreement, did not present candidates for the EP President. As such, the vote pitted the S&D’s David-Maria Sassoli (IT) against two former Spitzenkandidaten – Ska Keller (DE) of the Greens and Jan Zahradil (CZ) of the ACRE/ECR, alongside placeholder candidate Sira Rego (ES) of GUE. Sassoli was elected President for the first half of the 2019 – 2024 mandate, while the EPP (presumably EPP Spitzenkandidat Manfred Weber) would take the reins from January 2022. The vote was largely seen as a formality and a demonstration of the three largest Groups’ capacity to govern. However, Zahradil received almost 100 votes (more than the total votes of the ECR group), and Keller received almost twice as many votes as there are Greens/EFA MEPs. This forced a second round in which Sassoli was narrowly elected with just 11 more than the necessary simple majority. Close to 12% of MEPs did not cast a ballot. MEPs also elected 14 Vice-Presidents (VPs): Mairead McGuinness (EPP, IE), Pedro Silva Pereira (S&D, PT), Rainer Wieland (EPP, DE), Katarina Barley (S&D, DE), Othmar Karas (EPP, AT), Ewa Kopacz (EPP, PL), Klara Dobrev (S&D, HU), Dita Charanzová (RE, CZ), Nicola Beer (RE, DE), Lívia Járóka (EPP, HU) and Heidi Hautala (Greens/EFA, FI) were elected in the first ballot, while Marcel Kolaja (Greens/EFA, CZ), Dimitrios Papadimoulis (GUE/NGL, EL) and Fabio Massimo Castaldo (NI, IT) needed the second round. -

GREENRECOVERY REBOOT & REBOOST Our Economies for a Sustainable Future

GREENRECOVERY REBOOT & REBOOST our economies for a sustainable future Call for mobilisation The coronavirus crisis is shaking the whole world, with devastating consequences across Europe. We are being put to the test. We are suffering and mourning our losses, and this crisis is testing the limits of our system. It is also a test of our great European solidarity and of our institutions, which acted fast at the start of the crisis to deploy measures to protect us. The crisis is still ongoing, but we will see the light at the end of the tunnel, and by fighting together, we will beat the virus. Never have we faced such a challenging situation in peacetime. The fight against the pandemic is our top priority and everything that is needed to stop it and eradicate the virus must be done. We welcome and strongly support all the actions developed by governments, EU institutions, local authorities, scientists, medical staff, volunteers, citizens and economic actors. In this tremendously difficult situation, we are also facing another crisis: a shock to our economy tougher than the 2008 crisis. The major shock to the economy and workers created by the pandemic calls for a strong coordinated economic response. We therefore welcome the declaration of European leaders stating that they will do “whatever it takes” to tackle the social and economic consequences of this crisis. However, what worked for the 2008 financial crisis may not be sufficient to overcome this one. The economic recovery will only come with massive investments to protect and create jobs and to support all the companies, regions and sectors that have suffered from the economy coming to a sudden halt. -

En En Draft Agenda

European Parliament 2019 - 2024 Committee on Legal Affairs JURI(2021)0317_1 DRAFT AGENDA Meeting Wednesday 17 March 2021, 13.45 – 15.45 Brussels Room: József Antall (6Q1) and with remote participation of JURI Members 17 March 2021, 13.45 – 14.30 1. Adoption of agenda 2. Chair’s announcements 3. Approval of minutes of meetings 4. Subsidiarity (Rule 43) * * * 13.45 - Checking of the quorum and opening of the remote voting procedure Voting will be open from 13.50 to 15.45. *** Remote voting procedure *** OJ\PE689766v01-00en.rtf PE689.766v01-00 EN United in diversityEN *** Voting time *** 5. Liability of companies for environmental damage JURI/9/02513 2020/2027(INI) Rapporteur: Antonius Manders (PPE) PR – PE660.299v02-00 AM – PE663.019v01-00 Responsible: JURI Opinions: DEVE Caroline Roose (Verts/ALE) AD – PE658.987v02-00 AM – PE660.080v01-00 ENVI Pascal Canfin (Renew) AD – PE657.389v02-00 AM – PE661.797v01-00 LIBE Saskia Bricmont (Verts/ALE) AD – PE658.919v02-00 AM – PE658.928v01-00 Adoption of draft report Vote on amendments Deadline for tabling amendments:16 December 2020, 12.00 6. Amending Regulation (EC) No 1367/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 September 2006 on the application of the provisions of the Aarhus Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters to Community institutions and bodies JURI/9/04376 ***I 2020/0289(COD) COM(2020)0642 – C9-0321/2020 Rapporteur for the opinion: Jiří Pospíšil (PPE) PA – PE661.912v01-00 AM – PE680.916v01-00 Responsible: ENVI – Christian Doleschal (PPE) PR – PE662.051v01-00 AM – PE689.651v01-00 Adoption of draft opinion Vote on amendments Deadline for tabling amendments:4 February 2021, 12.00 7. -

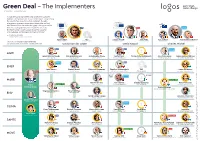

The Implementers 27 November – 31 December 2019

Green Deal – The Implementers 27 November – 31 December 2019 ”I want the European Green Deal to become Europe’s hallmark. At the heart of it is our commitment to becoming the world’s first climate-neutral continent. It is also a long-term economic imperative: those who act first and fastest will be the ones who grasp the opportunities Renew from the ecological transition. I want Europe to be EPP S&D Europe the front-runner. I want Europe to be the exporter of knowledge, technologies and best practice.” — Ursula von der Leyen President of the European Commission Bjoern Seibert TBD Lorenzo Mannelli Klaus Welle François Roux Jeppe Tranholm-Mikkelsen Head of cabinet Secretary General Head of cabinet Secretary General Head of cabinet Secretary General Executive Vice-President Frans Timmermans will coordinate the work on the European Green Deal. Ursula von der Leyen David Sassoli Charles Michel ECR EPP Renew Europe AGRI Janusz Wojciechowski Maciej Golubiewski Jerzy Bogdan Plewa Norbert Lins Tereza Pinto De Rezende Jari Juhani Leppä Sanna-Helena Fallenius Commissioner Head of Cabinet Director General AGRI Committee Chair AGRI Secretariat Minister of Agriculture Permanent Representation Renew ECR Europe ENER Kadri Simson Stefano Grassi Ditte Juul-Jørgensen Zdzisław Krasnodębski TBD Sanna Ek-Husson ITRE Secretariat S&D Commissioner Head of Cabinet Director General ITRE Acting Committee Chair Permanent Representation with ENVI with ENVI Pascal Renew Sara Blau Canfin Europe MARE Greens/EFA Bernhard Friess Chris Davies Claudio Quaranta Riitta Rahkonen -

Do Development Minister Characteristics Affect Aid Giving?

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Fuchs, Andreas; Richert, Katharina Working Paper Do Development Minister Characteristics Affect Aid Giving? Discussion Paper Series, No. 604 Provided in Cooperation with: Alfred Weber Institute, Department of Economics, University of Heidelberg Suggested Citation: Fuchs, Andreas; Richert, Katharina (2015) : Do Development Minister Characteristics Affect Aid Giving?, Discussion Paper Series, No. 604, University of Heidelberg, Department of Economics, Heidelberg, http://dx.doi.org/10.11588/heidok.00019769 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/127421 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von -

European Parliament Elections 2019 - Results

Briefing June 2019 European Parliament Elections 2019 - Results Austria – 18 MEPs Staff lead: Nick Dornheim PARTIES (EP group) Freedom Party of Austria The Greens – The Green Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) (EPP) Social Democratic Party of Austria NEOS – The New (FPÖ) (Salvini’s Alliance) – Alternative (Greens/EFA) – 7 seats (SPÖ) (S&D) - 5 seats Austria (ALDE) 1 seat 3 seats 2 seat 1. Othmar Karas* Andreas Schieder Harald Vilimsky* Werner Kogler Claudia Gamon 2. Karoline Edtstadler Evelyn Regner* Georg Mayer* Sarah Wiener 3. Angelika Winzig Günther Sidl Heinz Christian Strache 4. Simone Schmiedtbauer Bettina Vollath 5. Lukas Mandl* Hannes Heide 6. Alexander Bernhuber 7. Barbara Thaler NB 1: Only the parties reaching the 4% electoral threshold are mentioned in the table. *: Incumbent Member of the NB 2: 18 seats are allocated to Austria, same as in the previous election. European Parliament ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• www.eurocommerce.eu Belgium – 21 MEPs Staff lead: Stefania Moise PARTIES (EP group) DUTCH SPEAKING CONSITUENCY FRENCH SPEAKING CONSITUENCY GERMAN SPEAKING CONSTITUENCY 1. Geert Bourgeois 1. Pascal Arimont* 2. Assita Kanko 1. Maria Arena* Socialist Party (PS) Christian Social Party 3. Johan Van Overtveldt 2. Marc Tarabella* (S&D) 2 seats (CSP) (EPP) 1 seat New Flemish Alliance (N-VA) 1. Olivier Chastel (Greens/EFA) Reformist 2. Frédérique Ries* 4 seats Movement (MR) (ALDE) 2 seats 1. Philippe Lamberts* 2. Saskia Bricmont 1. Guy Verhofstadt* Ecolo (Greens/EFA) 2. Hilde Vautmans* 2 seats Open Flemish Liberals and Democrats (Open 1. Benoît Lutgen Humanist VLD) (ALDE) 2 seats democratic centre (cdH) (EPP) 1 seat 1. Kris Peeters Workers’ Party of 1. -

Parlament Europejski

28.5.2021 PL Dziennik Urzędo wy U nii Europejskiej C 203/1 Poniedziałek, 25 listopada 2019 r. IV (Informacje) INFORMACJE INSTYTUCJI, ORGANÓW I JEDNOSTEK ORGANIZACYJNYCH UNII EUROPEJSKIEJ PARLAMENT EUROPEJSKI SESJA 2019-2020 Posiedzenia od 25 do 28 listopada 2019 r. STRASBURG PROTOKÓŁ POSIEDZENIA W DNIU 25 LISTOPADA 2019 R. (2021/C 203/01) Spis treści Strona 1. Wznowienie sesji . 3 2. Otwarcie posiedzenia . 3 3. Oświadczenie Przewodniczącego . 3 4. Zatwierdzenie protokołów poprzednich posiedzeń . 3 5. Komunikaty Przewodniczącego . 3 6. Wnioski o uchylenie immunitetu . 4 7. Skład komisji i delegacji . 4 8. Sprostowania (art. 241 Regulaminu) (dalsze postępowanie) . 4 9. Negocjacje przed pierwszym czytaniem w Parlamencie (art. 71 Regulaminu) (podjęte działania) . 4 10. Podpisanie aktów przyjętych zgodnie ze zwykłą procedurą ustawodawczą (art. 79 Regulaminu) . 5 C 203/2 PL Dziennik Urzędo wy U nii Europejskiej 28.5.2021 Poniedziałek, 25 listopada 2019 r. Spis treści Strona 11. Pytania wymagające odpowiedzi ustnej (składanie dokumentów) . 5 12. Składanie dokumentów . 6 13. Porządek obrad . 8 14. Alarmująca sytuacja klimatyczna i środowiskowa — Konferencja ONZ w sprawie zmiany klimatu w 2019 r. 9 (COP25) (debata) . 15. Przystąpienie UE do konwencji stambulskiej i inne środki przeciwdziałania przemocy ze względu na płeć 10 (debata) . 16. Umowa UE-Ukraina zmieniająca preferencje handlowe w odniesieniu do mięsa drobiowego i przetworów 11 z mięsa drobiowego przewidziane w Układzie o stowarzyszeniu między UE a Ukrainą *** (debata) . 17. Trzydziesta rocznica aksamitnej rewolucji: znaczenie walki o wolność i demokrację w Europie Środkowo- 11 Wschodniej dla historycznego zjednoczenia Europy (debata) . 18. Postępowania wszczęte przez Rosję przeciwko litewskim sędziom, prokuratorom i śledczym prowadzącym 12 dochodzenie w sprawie tragicznych wydarzeń, do których doszło w Wilnie 13 stycznia 1991 r.