A Plant Ecological Study and Management Plan for Mogale's Gate Biodiversity Centre, Gauteng

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delivering Sustainable Growth

Petra Diamonds Limited Sustainability Report 2013 Delivering sustainable growth _0_PDL_csr13_[NB_MR].indd 1 11/27/2013 5:06:01 PM Above: Johannes Louw and Tsepso Kido, who work on the ground handling section on 620m level at Finsch. Front cover: The Vaal River, one of South Africa’s major rivers and a supplier of water to large areas of the country, including Finsch and its local communities. _0_PDL_csr13_[NB_MR].indd 2 11/27/2013 5:06:01 PM Overview Contents Sustainability is at the heart of Petra Diamonds. The Company is committed to the responsible development of its assets to the benefit of all stakeholders and its operations are planned and structured Overview with their long-term success in mind. Strategy and Governance Health and Safety Health and Safety Our People Environment Community Page 24 Page 30 Page 37 Page 50 1 Overview Petra aims to operate according to 2 Company profile 2 Scope of this report the highest ethical and governance 3 FY 2013 highlights 4 Our business People Our standards and seeks to achieve 6 Our operations 8 Our commitment leading environmental, social and 9 Key Performance Indicators 12 CEO’s statement health and safety performance. 14 Strategy and Governance 15 Responsible leadership 21 The regulatory environment for mining in South Africa 22 Case study: Induction of new Non-Executive Directors 23 Case study: Cullinan inspires new generation of South African artists 24 Health and Safety Environment 25 Striving for Zero Harm 28 What is OHSAS 18001? 29 Case study: Combatting the ‘Silly Season’ 29 What is -

Freshwater Fishes

WESTERN CAPE PROVINCE state oF BIODIVERSITY 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction 2 Chapter 2 Methods 17 Chapter 3 Freshwater fishes 18 Chapter 4 Amphibians 36 Chapter 5 Reptiles 55 Chapter 6 Mammals 75 Chapter 7 Avifauna 89 Chapter 8 Flora & Vegetation 112 Chapter 9 Land and Protected Areas 139 Chapter 10 Status of River Health 159 Cover page photographs by Andrew Turner (CapeNature), Roger Bills (SAIAB) & Wicus Leeuwner. ISBN 978-0-620-39289-1 SCIENTIFIC SERVICES 2 Western Cape Province State of Biodiversity 2007 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Andrew Turner [email protected] 1 “We live at a historic moment, a time in which the world’s biological diversity is being rapidly destroyed. The present geological period has more species than any other, yet the current rate of extinction of species is greater now than at any time in the past. Ecosystems and communities are being degraded and destroyed, and species are being driven to extinction. The species that persist are losing genetic variation as the number of individuals in populations shrinks, unique populations and subspecies are destroyed, and remaining populations become increasingly isolated from one another. The cause of this loss of biological diversity at all levels is the range of human activity that alters and destroys natural habitats to suit human needs.” (Primack, 2002). CapeNature launched its State of Biodiversity Programme (SoBP) to assess and monitor the state of biodiversity in the Western Cape in 1999. This programme delivered its first report in 2002 and these reports are updated every five years. The current report (2007) reports on the changes to the state of vertebrate biodiversity and land under conservation usage. -

Aspects of the Ecology and Conservation of Frogs in Urban Habitats of South Africa

Frogs about town: Aspects of the ecology and conservation of frogs in urban habitats of South Africa DJD Kruger 20428405 Thesis submitted for the degree Philosophiae Doctor in Zoology at the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University Supervisor: Prof LH du Preez Co-supervisor: Prof C Weldon September 2014 i In loving memory of my grandmother, Kitty Lombaard (1934/07/09 – 2012/05/18), who has made an invaluable difference in all aspects of my life. ii Acknowledgements A project with a time scale and magnitude this large leaves one indebted by numerous people that contributed to the end result of this study. I would like to thank the following people for their invaluable contributions over the past three years, in no particular order: To my supervisor, Prof. Louis du Preez I am indebted, not only for the help, guidance and support he has provided throughout this study, but also for his mentorship and example he set in all aspects of life. I also appreciate the help of my co-supervisor, Prof. Ché Weldon, for the numerous contributions, constructive comments and hours spent on proofreading. I owe thanks to all contributors for proofreading and language editing and thereby correcting my “boerseun” English grammar but also providing me with professional guidance. Prof. Louis du Preez, Prof. Ché Weldon, Dr. Andrew Hamer, Dr. Kirsten Parris, Prof. John Malone and Dr. Jeanne Tarrant are all dearly thanked for invaluable comments on earlier drafts of parts/the entirety of this thesis. For statistical contributions I am especially also grateful to Dr. Andrew Hamer for help with Bayesian analysis and to the North-West Statistical Services consultant, Dr. -

The Birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an Annotated Checklist

European Journal of Taxonomy 306: 1–69 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2017.306 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2017 · Gedeon K. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A32EAE51-9051-458A-81DD-8EA921901CDC The birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an annotated checklist Kai GEDEON 1,*, Chemere ZEWDIE 2 & Till TÖPFER 3 1 Saxon Ornithologists’ Society, P.O. Box 1129, 09331 Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Germany. 2 Oromia Forest and Wildlife Enterprise, P.O. Box 1075, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia. 3 Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, Centre for Taxonomy and Evolutionary Research, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 3 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F46B3F50-41E2-4629-9951-778F69A5BBA2 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F59FEDB3-627A-4D52-A6CB-4F26846C0FC5 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:A87BE9B4-8FC6-4E11-8DB4-BDBB3CFBBEAA Abstract. Oromia is the largest National Regional State of Ethiopia. Here we present the first comprehensive checklist of its birds. A total of 804 bird species has been recorded, 601 of them confirmed (443) or assumed (158) to be breeding birds. At least 561 are all-year residents (and 31 more potentially so), at least 73 are Afrotropical migrants and visitors (and 44 more potentially so), and 184 are Palaearctic migrants and visitors (and eight more potentially so). Three species are endemic to Oromia, 18 to Ethiopia and 43 to the Horn of Africa. 170 Oromia bird species are biome restricted: 57 to the Afrotropical Highlands biome, 95 to the Somali-Masai biome, and 18 to the Sudan-Guinea Savanna biome. -

South Africa: Magoebaskloof and Kruger National Park Custom Tour Trip Report

SOUTH AFRICA: MAGOEBASKLOOF AND KRUGER NATIONAL PARK CUSTOM TOUR TRIP REPORT 24 February – 2 March 2019 By Jason Boyce This Verreaux’s Eagle-Owl showed nicely one late afternoon, puffing up his throat and neck when calling www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | TRIP REPORT South Africa: Magoebaskloof and Kruger National Park February 2019 Overview It’s common knowledge that South Africa has very much to offer as a birding destination, and the memory of this trip echoes those sentiments. With an itinerary set in one of South Africa’s premier birding provinces, the Limpopo Province, we were getting ready for a birding extravaganza. The forests of Magoebaskloof would be our first stop, spending a day and a half in the area and targeting forest special after forest special as well as tricky range-restricted species such as Short-clawed Lark and Gurney’s Sugarbird. Afterwards we would descend the eastern escarpment and head into Kruger National Park, where we would make our way to the northern sections. These included Punda Maria, Pafuri, and the Makuleke Concession – a mouthwatering birding itinerary that was sure to deliver. A pair of Woodland Kingfishers in the fever tree forest along the Limpopo River Detailed Report Day 1, 24th February 2019 – Transfer to Magoebaskloof We set out from Johannesburg after breakfast on a clear Sunday morning. The drive to Polokwane took us just over three hours. A number of birds along the way started our trip list; these included Hadada Ibis, Yellow-billed Kite, Southern Black Flycatcher, Village Weaver, and a few brilliant European Bee-eaters. -

The Eco-Ethology of the Karoo Korhaan Eupodotis Virgorsil

THE ECO-ETHOLOGY OF THE KAROO KORHAAN EUPODOTIS VIGORSII. BY M.G.BOOBYER University of Cape Town SUBMITIED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE (ORNITHOLOGY) UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN RONDEBOSCH 7700 CAPE TOWN The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town University of Cape Town PREFACE The study of the Karoo Korhaan allowed me a far broader insight in to the Karoo than would otherwise have been possible. The vast openness of the Karoo is a monotony to those who have not stopped and looked. Many people were instrumental in not only encouraging me to stop and look but also in teaching me to see. The farmers on whose land I worked are to be applauded for their unquestioning approval of my activities and general enthusiasm for studies concerning the veld and I am particularly grateful to Mnr. and Mev. Obermayer (Hebron/Merino), Mnr. and Mev. Steenkamp (Inverdoorn), Mnr. Bothma (Excelsior) and Mnr. Van der Merwe. Alwyn and Joan Pienaar of Bokvlei have my deepest gratitude for their generous hospitality and firm friendship. Richard and Sue Dean were a constant source of inspiration throughout the study and their diligence and enthusiasm in the field is an example to us all. -

Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention

Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention: the role of the Convention on Wetlands in the Conservation and Wise Use of Biodiversity edited by A. J. Hails Ramsar Convention Bureau Ministry of Environment and Forest, India 1996 [1997] Published by the Ramsar Convention Bureau, Gland, Switzerland, with the support of: • the General Directorate of Natural Resources and Environment, Ministry of the Walloon Region, Belgium • the Royal Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Denmark • the National Forest and Nature Agency, Ministry of the Environment and Energy, Denmark • the Ministry of Environment and Forests, India • the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Sweden Copyright © Ramsar Convention Bureau, 1997. Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior perinission from the copyright holder, providing that full acknowledgement is given. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. The views of the authors expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect those of the Ramsar Convention Bureau or of the Ministry of the Environment of India. Note: the designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Ranasar Convention Bureau concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Citation: Halls, A.J. (ed.), 1997. Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention: The Role of the Convention on Wetlands in the Conservation and Wise Use of Biodiversity. -

TNP SOK 2011 Internet

GARDEN ROUTE NATIONAL PARK : THE TSITSIKAMMA SANP ARKS SECTION STATE OF KNOWLEDGE Contributors: N. Hanekom 1, R.M. Randall 1, D. Bower, A. Riley 2 and N. Kruger 1 1 SANParks Scientific Services, Garden Route (Rondevlei Office), PO Box 176, Sedgefield, 6573 2 Knysna National Lakes Area, P.O. Box 314, Knysna, 6570 Most recent update: 10 May 2012 Disclaimer This report has been produced by SANParks to summarise information available on a specific conservation area. Production of the report, in either hard copy or electronic format, does not signify that: the referenced information necessarily reflect the views and policies of SANParks; the referenced information is either correct or accurate; SANParks retains copies of the referenced documents; SANParks will provide second parties with copies of the referenced documents. This standpoint has the premise that (i) reproduction of copywrited material is illegal, (ii) copying of unpublished reports and data produced by an external scientist without the author’s permission is unethical, and (iii) dissemination of unreviewed data or draft documentation is potentially misleading and hence illogical. This report should be cited as: Hanekom N., Randall R.M., Bower, D., Riley, A. & Kruger, N. 2012. Garden Route National Park: The Tsitsikamma Section – State of Knowledge. South African National Parks. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................2 2. ACCOUNT OF AREA........................................................................................................2 -

Birding Tour to Ghana Specializing on Upper Guinea Forest 12–26 January 2018

Birding Tour to Ghana Specializing on Upper Guinea Forest 12–26 January 2018 Chocolate-backed Kingfisher, Ankasa Resource Reserve (Dan Casey photo) Participants: Jim Brown (Missoula, MT) Dan Casey (Billings and Somers, MT) Steve Feiner (Portland, OR) Bob & Carolyn Jones (Billings, MT) Diane Kook (Bend, OR) Judy Meredith (Bend, OR) Leaders: Paul Mensah, Jackson Owusu, & Jeff Marks Prepared by Jeff Marks Executive Director, Montana Bird Advocacy Birding Ghana, Montana Bird Advocacy, January 2018, Page 1 Tour Summary Our trip spanned latitudes from about 5° to 9.5°N and longitudes from about 3°W to the prime meridian. Weather was characterized by high cloud cover and haze, in part from Harmattan winds that blow from the northeast and carry particulates from the Sahara Desert. Temperatures were relatively pleasant as a result, and precipitation was almost nonexistent. Everyone stayed healthy, the AC on the bus functioned perfectly, the tropical fruits (i.e., bananas, mangos, papayas, and pineapples) that Paul and Jackson obtained from roadside sellers were exquisite and perfectly ripe, the meals and lodgings were passable, and the jokes from Jeff tolerable, for the most part. We detected 380 species of birds, including some that were heard but not seen. We did especially well with kingfishers, bee-eaters, greenbuls, and sunbirds. We observed 28 species of diurnal raptors, which is not a large number for this part of the world, but everyone was happy with the wonderful looks we obtained of species such as African Harrier-Hawk, African Cuckoo-Hawk, Hooded Vulture, White-headed Vulture, Bat Hawk (pair at nest!), Long-tailed Hawk, Red-chested Goshawk, Grasshopper Buzzard, African Hobby, and Lanner Falcon. -

The Gambia: a Taste of Africa, November 2017

Tropical Birding - Trip Report The Gambia: A Taste of Africa, November 2017 A Tropical Birding “Chilled” SET DEPARTURE tour The Gambia A Taste of Africa Just Six Hours Away From The UK November 2017 TOUR LEADERS: Alan Davies and Iain Campbell Report by Alan Davies Photos by Iain Campbell Egyptian Plover. The main target for most people on the tour www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] p.1 Tropical Birding - Trip Report The Gambia: A Taste of Africa, November 2017 Red-throated Bee-eaters We arrived in the capital of The Gambia, Banjul, early evening just as the light was fading. Our flight in from the UK was delayed so no time for any real birding on this first day of our “Chilled Birding Tour”. Our local guide Tijan and our ground crew met us at the airport. We piled into Tijan’s well used minibus as Little Swifts and Yellow-billed Kites flew above us. A short drive took us to our lovely small boutique hotel complete with pool and lovely private gardens, we were going to enjoy staying here. Having settled in we all met up for a pre-dinner drink in the warmth of an African evening. The food was delicious, and we chatted excitedly about the birds that lay ahead on this nine- day trip to The Gambia, the first time in West Africa for all our guests. At first light we were exploring the gardens of the hotel and enjoying the warmth after leaving the chilly UK behind. Both Red-eyed and Laughing Doves were easy to see and a flash of colour announced the arrival of our first Beautiful Sunbird, this tiny gem certainly lived up to its name! A bird flew in landing in a fig tree and again our jaws dropped, a Yellow-crowned Gonolek what a beauty! Shocking red below, black above with a daffodil yellow crown, we were loving Gambian birds already. -

Namibia & the Okavango

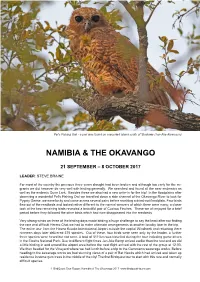

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen. -

Species Accounts

Species accounts The list of species that follows is a synthesis of all the botanical knowledge currently available on the Nyika Plateau flora. It does not claim to be the final word in taxonomic opinion for every plant group, but will provide a sound basis for future work by botanists, phytogeographers, and reserve managers. It should also serve as a comprehensive plant guide for interested visitors to the two Nyika National Parks. By far the largest body of information was obtained from the following nine publications: • Flora zambesiaca (current ed. G. Pope, 1960 to present) • Flora of Tropical East Africa (current ed. H. Beentje, 1952 to present) • Plants collected by the Vernay Nyasaland Expedition of 1946 (Brenan & collaborators 1953, 1954) • Wye College 1972 Malawi Project Final Report (Brummitt 1973) • Resource inventory and management plan for the Nyika National Park (Mill 1979) • The forest vegetation of the Nyika Plateau: ecological and phenological studies (Dowsett-Lemaire 1985) • Biosearch Nyika Expedition 1997 report (Patel 1999) • Biosearch Nyika Expedition 2001 report (Patel & Overton 2002) • Evergreen forest flora of Malawi (White, Dowsett-Lemaire & Chapman 2001) We also consulted numerous papers dealing with specific families or genera and, finally, included the collections made during the SABONET Nyika Expedition. In addition, botanists from K and PRE provided valuable input in particular plant groups. Much of the descriptive material is taken directly from one or more of the works listed above, including information regarding habitat and distribution. A single illustration accompanies each genus; two illustrations are sometimes included in large genera with a wide morphological variance (for example, Lobelia).