3. Baker, the Law's Two Bodies, 60-90.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chronicles of the Family Baker"

Chronicles of the Family by Lee C.Baker i ii Table of Contents 1 THE MEDIEVAL BAKERS........................................................................................1 2 THE BAKERS OF SISSINGHURST.........................................................................20 3 THE BAKERS OF LONDON AND OXFORD ............................................................49 4 THE BAKERS AT HOTHFIELD ..............................................................................58 5 COMING OUT OF ENGLAND.................................................................................70 6 THE DAYS AT MILFORD .......................................................................................85 7 EAST HAMPTON, L. I. ...........................................................................................96 8 AMAGANSETT BY THE SEA ................................................................................114 9 STATEN ISLAND AND NEW AMSTERDAM ..........................................................127 10 THE ELIZABETH TOWN PIONEERS ....................................................................138 11 THE BAKERS OF ELIZABETH TOWN AND WESTFIELD ......................................171 12 THE NEIGHBORS AT NEWARK...........................................................................198 13 THE NEIGHBORS AT RAHWAY ...........................................................................208 14 WHO IS JONATHAN BAKER?..............................................................................219 15 THE JONATHAN I. BAKER CONFUSION -

Conversations with Professor Sir John Hamilton Baker Part 3: Published Works by Lesley Dingle1 and Daniel Bates2 Date: 31 March 2017

Conversations with Professor Sir John Hamilton Baker Part 3: Published works by Lesley Dingle1 and Daniel Bates2 Date: 31 March 2017 This is the third interview with the twenty-fifth personality for the Eminent Scholars Archive. Professor Sir John Baker is Emeritus Downing Professor of the Laws of England at the University of Cambridge. The interview was recorded, and the audio version is available on this website. Questions in the interviews are sequentially numbered for use in a database of citations to personalities mentioned across the Eminent Scholars Archive. Interviewer: Lesley Dingle, her questions are in bold type. Professor Baker’s answers are in normal type. Comments added by LD, [in italics]. Footnotes added by LD. 178. Professor Baker, we now come to the point where we can discuss your scholarly works and the research that you have undertaken over the last half a century to produce them. To say that you have been very productive and that your output has been impressive would be to understate your contribution to scholarly legal history. Your CV lists 38 books, 123 chapters in books, 183 articles and notes, 12 pamphlets, 35 book reviews and 97 invited lectures. Also, remembering that you have always had a full academic life of lecturing, administration and activity in learned societies puts these achievements even more clearly into perspective. It would have been impossible for me to have read more than a small percentage of this material and, consequently, I hope you will forgive me for having been very selective in the books and the papers that I have looked at in detail. -

Speakers of the House of Commons

Parliamentary Information List BRIEFING PAPER 04637a 21 August 2015 Speakers of the House of Commons Speaker Date Constituency Notes Peter de Montfort 1258 − William Trussell 1327 − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Styled 'Procurator' Henry Beaumont 1332 (Mar) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Sir Geoffrey Le Scrope 1332 (Sep) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Probably Chief Justice. William Trussell 1340 − William Trussell 1343 − Appeared for the Commons alone. William de Thorpe 1347-1348 − Probably Chief Justice. Baron of the Exchequer, 1352. William de Shareshull 1351-1352 − Probably Chief Justice. Sir Henry Green 1361-1363¹ − Doubtful if he acted as Speaker. All of the above were Presiding Officers rather than Speakers Sir Peter de la Mare 1376 − Sir Thomas Hungerford 1377 (Jan-Mar) Wiltshire The first to be designated Speaker. Sir Peter de la Mare 1377 (Oct-Nov) Herefordshire Sir James Pickering 1378 (Oct-Nov) Westmorland Sir John Guildesborough 1380 Essex Sir Richard Waldegrave 1381-1382 Suffolk Sir James Pickering 1383-1390 Yorkshire During these years the records are defective and this Speaker's service might not have been unbroken. Sir John Bussy 1394-1398 Lincolnshire Beheaded 1399 Sir John Cheyne 1399 (Oct) Gloucestershire Resigned after only two days in office. John Dorewood 1399 (Oct-Nov) Essex Possibly the first lawyer to become Speaker. Sir Arnold Savage 1401(Jan-Mar) Kent Sir Henry Redford 1402 (Oct-Nov) Lincolnshire Sir Arnold Savage 1404 (Jan-Apr) Kent Sir William Sturmy 1404 (Oct-Nov) Devonshire Or Esturmy Sir John Tiptoft 1406 Huntingdonshire Created Baron Tiptoft, 1426. -

CHURCH: Dates of Confirmation/Consecration

Court: Women at Court; Royal Household. p.1: Women at Court. Royal Household: p.56: Gentlemen and Grooms of the Privy Chamber; p.59: Gentlemen Ushers. p.60: Cofferer and Controller of the Household. p.61: Privy Purse and Privy Seal: selected payments. p.62: Treasurer of the Chamber: selected payments; p.63: payments, 1582. p.64: Allusions to the Queen’s family: King Henry VIII; Queen Anne Boleyn; King Edward VI; Queen Mary Tudor; Elizabeth prior to her Accession. Royal Household Orders. p.66: 1576 July (I): Remembrance of charges. p.67: 1576 July (II): Reformations to be had for diminishing expenses. p.68: 1577 April: Articles for diminishing expenses. p.69: 1583 Dec 7: Remembrances concerning household causes. p.70: 1598: Orders for the Queen’s Almoners. 1598: Orders for the Queen’s Porters. p.71: 1599: Orders for supplying French wines to the Royal Household. p.72: 1600: Thomas Wilson: ‘The Queen’s Expenses’. p.74: Marriages: indexes; miscellaneous references. p.81: Godchildren: indexes; miscellaneous references. p.92: Deaths: chronological list. p.100: Funerals. Women at Court. Ladies and Gentlewomen of the Bedchamber and the Privy Chamber. Maids of Honour, Mothers of the Maids; also relatives and friends of the Queen not otherwise included, and other women prominent in the reign. Close friends of the Queen: Katherine Astley; Dorothy Broadbelt; Lady Cobham; Anne, Lady Hunsdon; Countess of Huntingdon; Countess of Kildare; Lady Knollys; Lady Leighton; Countess of Lincoln; Lady Norris; Elizabeth and Helena, Marchionesses of Northampton; Countess of Nottingham; Blanche Parry; Katherine, Countess of Pembroke; Mary Radcliffe; Lady Scudamore; Lady Mary Sidney; Lady Stafford; Countess of Sussex; Countess of Warwick. -

DISSERTATION-Submission Reformatted

The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 By Robert Lee Harkins A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor David Bates Fall 2013 © Robert Lee Harkins 2013 All Rights Reserved 1 Abstract The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 by Robert Lee Harkins Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair This study examines the problem of religious and political obedience in early modern England. Drawing upon extensive manuscript research, it focuses on the reign of Mary I (1553-1558), when the official return to Roman Catholicism was accompanied by the prosecution of Protestants for heresy, and the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603), when the state religion again shifted to Protestantism. I argue that the cognitive dissonance created by these seesaw changes of official doctrine necessitated a society in which religious mutability became standard operating procedure. For most early modern men and women it was impossible to navigate between the competing and contradictory dictates of Tudor religion and politics without conforming, dissimulating, or changing important points of conscience and belief. Although early modern theologians and polemicists widely declared religious conformists to be shameless apostates, when we examine specific cases in context it becomes apparent that most individuals found ways to positively rationalize and justify their respective actions. This fraught history continued to have long-term effects on England’s religious, political, and intellectual culture. -

![Complete Baronetage of 1720," to Which [Erroneous] Statement Brydges Adds](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5807/complete-baronetage-of-1720-to-which-erroneous-statement-brydges-adds-845807.webp)

Complete Baronetage of 1720," to Which [Erroneous] Statement Brydges Adds

cs CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 3 1924 092 524 374 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu31924092524374 : Complete JSaronetage. EDITED BY Gr. Xtl. C O- 1^ <»- lA Vi «_ VOLUME I. 1611—1625. EXETER WILLIAM POLLAKD & Co. Ltd., 39 & 40, NORTH STREET. 1900. Vo v2) / .|vt POirARD I S COMPANY^ CONTENTS. FACES. Preface ... ... ... v-xii List of Printed Baronetages, previous to 1900 xiii-xv Abbreviations used in this work ... xvi Account of the grantees and succeeding HOLDERS of THE BARONETCIES OF ENGLAND, CREATED (1611-25) BY JaMES I ... 1-222 Account of the grantees and succeeding holders of the baronetcies of ireland, created (1619-25) by James I ... 223-259 Corrigenda et Addenda ... ... 261-262 Alphabetical Index, shewing the surname and description of each grantee, as above (1611-25), and the surname of each of his successors (being Commoners) in the dignity ... ... 263-271 Prospectus of the work ... ... 272 PREFACE. This work is intended to set forth the entire Baronetage, giving a short account of all holders of the dignity, as also of their wives, with (as far as can be ascertained) the name and description of the parents of both parties. It is arranged on the same principle as The Complete Peerage (eight vols., 8vo., 1884-98), by the same Editor, save that the more convenient form of an alphabetical arrangement has, in this case, had to be abandoned for a chronological one; the former being practically impossible in treating of a dignity in which every holder may (and very many actually do) bear a different name from the grantee. -

Sir Edward Coke and the Elizabethan Origins of Judicial Review Allen Dillard Boyer

Boston College Law Review Volume 39 Article 2 Issue 1 Number 1 12-1-1998 "Understanding,Authority, and Will": Sir Edward Coke and the Elizabethan Origins of Judicial Review Allen Dillard Boyer Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Allen D. Boyer, "Understanding,Authority, and Will": Sir Edward Coke and the Elizabethan Origins of Judicial Review, 39 B.C.L. Rev. 43 (1998), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol39/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "UNDERSTANDING, AUTHORITY, AND WILL": SIR EDWARD COKE AND THE ELIZABETHAN ORIGINS OF JUDICIAL REVIEW ALLEN DILLARD BOYER * Bacon and Shakespeare: what they were to philosophy and litera ture, Coke was to the common law. • J.H. Baker I. INTRODUCTION Of all important jurisprudents, Sir Edward Coke is the most infu- riatingly conventional. Despite the drama which often attended his career—his cross-examination of Sir Walter Raleigh, his role in uncov- ering the Gunpowder Plot, his bitter rivalry with Sir Francis Bacon and his explosive face-to-face confrontations with King James I—Coke's work presents a studied calm.' Coke explains rather than critiques. He describes and justifies existing legal rules rather than working out how the law provides rules for making rules. -

Table of Contents TABLE of CONTENTS

Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ...............................................................................................................................................................................1 THE STORY TELLERS.............................................................................................................................................................................. 10 BAKER.......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 10 BECKER , BEAKER ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Richard Baker......................................................................................................................................................................................... 11 Deannes Baker........................................................................................................................................................................................ 11 Simon Baker*.......................................................................................................................................................................................... 11 John Baker............................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Court: Women at Court, and the Royal Household (100

Court: Women at Court; Royal Household. p.1: Women at Court. Royal Household: p.56: Gentlemen and Grooms of the Privy Chamber; p.59: Gentlemen Ushers. p.60: Cofferer and Controller of the Household. p.61: Privy Purse and Privy Seal: selected payments. p.62: Treasurer of the Chamber: selected payments; p.63: payments, 1582. p.64: Allusions to the Queen’s family: King Henry VIII; Queen Anne Boleyn; King Edward VI; Queen Mary Tudor; Elizabeth prior to her Accession. Royal Household Orders. p.66: 1576 July (I): Remembrance of charges. p.67: 1576 July (II): Reformations to be had for diminishing expenses. p.68: 1577 April: Articles for diminishing expenses. p.69: 1583 Dec 7: Remembrances concerning household causes. p.70: 1598: Orders for the Queen’s Almoners. 1598: Orders for the Queen’s Porters. p.71: 1599: Orders for supplying French wines to the Royal Household. p.72: 1600: Thomas Wilson: ‘The Queen’s Expenses’. p.74: Marriages: indexes; miscellaneous references. p.81: Godchildren: indexes; miscellaneous references. p.92: Deaths: chronological list. p.100: Funerals. Women at Court. Ladies and Gentlewomen of the Bedchamber and the Privy Chamber. Maids of Honour, Mothers of the Maids; also relatives and friends of the Queen not otherwise included, and other women prominent in the reign. Close friends of the Queen: Katherine Astley; Dorothy Broadbelt; Lady Cobham; Anne, Lady Hunsdon; Countess of Huntingdon; Countess of Kildare; Lady Knollys; Lady Leighton; Countess of Lincoln; Lady Norris; Elizabeth and Helena, Marchionesses of Northampton; Countess of Nottingham; Blanche Parry; Katherine, Countess of Pembroke; Mary Radcliffe; Lady Scudamore; Lady Mary Sidney; Lady Stafford; Countess of Sussex; Countess of Warwick. -

Register of the Society of Colonial Wars in the District of Columbia, 1904

RegisteroftheSocietyColonialWarsinDistrictColumbia,1904... Society GeneralofColonialWars(U.S.).DistrictColumbia,AlbertCharlesPeale * GENERAL L IBRARY of the UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN -PRESENTED B Y- &,. S QTS^JLA/U- ^ >^ CXJ3. 1 'JY\ ^£>_ \^q5 IL. % 3 D 6 3 With t he uaMi"LiMENT9 of the Societyf o Coloxial, Wars . IXHE T UISTRILT OP- OOLUMllIA Kendall B uilding WALTER C. CT.EPIIAN10 Washington, 1 J. C. .Secretary. (2*--cii~ J -I e o > REGISTER SOCIETYF O COLONIAL WARS INHE T DISTRICTF O COLUMBIA 1904 FORTITERRO P PATRIA WASHINGTON C ITY 1904 Prepared f or the Society by Dr. A. C. Peale, the Registrar, and edited by Dr. Marcus Benjamin, the Deputy-Governor under the direction of the following Committee on Publication: Thomas H yde, Chairman; A. C. Peale, A. Howard Clark, Marcus Benjamin, Frank B. Smith. (§&tttB, ( Stnlltmsn of tlu? (Boratril. ana fciattotng QIommittrfB. Governor, Thomas H yde. Deputy-Governor, Marcus B enjamin, Ph. D. Lieutenant-Governor, W illiam Van Zandt Cox. Secretary, F rank Birge. Smith, (1632 Riggs Place.) Treasurer. John W illiam Henry, (1315 F S treet.) Registrar. A lbert Charles Peale, M. D. Historian, G ilbert Thompson. Chaplain, R ev. Caleb Rochford Stetson. Chancellor, L eonard Huntress Dyer. Surgeon. H enry Lowry Emilius Johnson, M. D. Gentlemen o f the Council. (Term expires December, 1904.) George C olton Maynard, Frederic Wolters Huidekoper, Thomas B lagden. (Term e xpires December, 1905.) George W ashington Neale Curtis, M. D., John D ewhurst Patten, Job Barciard. (Term e xpires December, 1906.) Alonzo H oward Clark, Zebina Moses. Samuel W alter Woodward. Committee o n Membership. Albert C harles Peale, M. -

Prominent Elizabethans

Prominent Elizabethans. p.1: Church; p.2: Law Officers. p.3: Miscellaneous Officers of State. p.5: Royal Household Officers. p.7: Privy Councillors. p.9: Peerages. p.11: Knights of the Garter and Garter ceremonies. p.18: Knights: chronological list; p.22: alphabetical list. p.26: Knights: miscellaneous references; Knights of St Michael. p.27-162: Prominent Elizabethans. Church: Archbishops, two Bishops, four Deans. Dates of confirmation/consecration. Archbishop of Canterbury. 1556: Reginald Pole, Archbishop and Cardinal; died 1558 Nov 17. Vacant 1558-1559 December. 1559 Dec 17: Matthew Parker; died 1575 May 17. 1576 Feb 15: Edmund Grindal; died 1583 July 6. 1583 Sept 23: John Whitgift; died 1604. Archbishop of York. 1555: Nicholas Heath; deprived 1559 July 5. 1560 Aug 8: William May elected; died the same day. 1561 Feb 25: Thomas Young; died 1568 June 26. 1570 May 22: Edmund Grindal; became Archbishop of Canterbury 1576. 1577 March 8: Edwin Sandys; died 1588 July 10. 1589 Feb 19: John Piers; died 1594 Sept 28. 1595 March 24: Matthew Hutton; died 1606. Bishop of London. 1553: Edmund Bonner; deprived 1559 May 29; died in prison 1569. 1559 Dec 21: Edmund Grindal; became Archbishop of York 1570. 1570 July 13: Edwin Sandys; became Archbishop of York 1577. 1577 March 24: John Aylmer; died 1594 June 5. 1595 Jan 10: Richard Fletcher; died 1596 June 15. 1597 May 8: Richard Bancroft; became Archbishop of Canterbury 1604. Bishop of Durham. 1530: Cuthbert Tunstall; resigned 1559 Sept 28; died Nov 18. 1561 March 2: James Pilkington; died 1576 Jan 23. 1577 May 9: Richard Barnes; died 1587 Aug 24. -

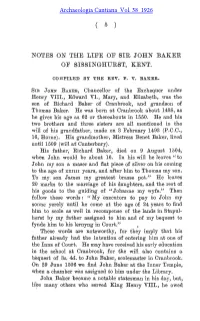

Notes on the Life of Sir John Baker of Sissinghurst, Kent

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 38 1926 NOTES ON THE LIFE OF SIR, JOHN BAKER OF SISSINGHURST, KENT. COMPILED BY THE REV. F. V. BAKER. SIB JOHN BAKER, Chancellor of the Exchequer under Henry VIII., Edward VI., Mary, and Elizabeth, was the son of Richard Baker of Cranbrook, and grandson of Thomas Baker. He was born at Cranbrook about 1488, as he gives his age as 62 or thereabouts in 1550. He and his two brothers and three sisters are all mentioned in the will of his grandfather, made on 3 February 1493 (P.C.C., 16, Home). His grandmother, Mistress Benet Baker, lived until 1509 (will at'Canterbury). His father, Richard Baker, died on 9 August 1504, when John would be about 16. In his will he leaves " to John my son a niaser and flat piece of silver on his coming to the age of xxiui years, and after him to Thomas my son. To my. son James my greatest brasse pot." He leaves 20 marks to the marriage of his daughters, and the rest of his goods to the guiding of "Johanne my wyfe." Then follow these words: " My executors to pay to John my sonne yerely until he come at the age of 24 years to find him to scole as well in recompense of the lands in Stapul- her'st by my father assigned to him and of my bequest to fynde him to his lernyng in Court." These words are noteworthy, for they imply that his father already had the intention of entering him at one of the Inns of Court.