PP 163-180, Coastal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Saga of Community Learning: Mariculture and the Bolinao Experience Laura T

The saga of community learning: Mariculture and the Bolinao experience Laura T. David, Davelyn Pastor-Rengel, Liana Talaue-McManus, Evangeline Magdaong, Rose Salalila-Aruelo, Helen Grace Bangi, Maria Lourdes San Diego-McGlone, Cesar Villanoy, Patience F. Ventura, Ralph Vincent Basilio and Kristina Cordero-Bailey* Aquatic Ecosystem Health & Management, 17(2):196–204, 2014. DOI: 10.1080/14634988.2014.910488 Food security for the Filipinos Current population of the Philippines 104.9 Million (2017) Philippine Fisheries Code RA 8550 10% municipal waters for aquaculture Bolinao-Anda, Pangasinan Mariculture of milkfish (bangus) and mussels • Began 1970’s and 1980’s • Boom in the 1990’s Bolinao Municipal Fisheries Ordinance 1999 Fish kills Date of Satellite Spatial acquisition resolution 3 November Quickbird 2.4m 2002 19 June 2006 Formosat 2m (panchromatic) 7 March Worldview-2 1.84m 2010 12 December Worldview-2 1.84m 2010 Fish cages Fish pens Fyke nets 2002 Quickbird Formosat Worldview-2 Worldview-2 (Nov 2002) (Jun 2006) (Mar 2010) (Dec 2010) Cages 265 230 213 217 Pens 56 71 167 149 TOTAL 321 301 380 366 2006 2010 Mariculture structures in Bolinao, Pangasinan Mariculture structures in Bolinao-Anda, Pangasinan Formosat (Jun Worldview-2 Worldview-2 2006) (March 2010) (December 2010) Cages 342 267 287 Pens 288 507 539 Fyke nets n/a 53 79 TOTAL 630 827 905 Approaches for sustainable mariculture Recommendation 1: Reduce density of mariculture facilities to 35% of existing structures Approaches for sustainable mariculture Recommendation 2: Develop and deploy a multi-sectoral monitoring system Water Quality Monitoring Teams (WQMTs) • Nutrients • Dissolved oxygen • Plankton • NOAA CRW hotspot products ➢ Mariculture operators ➢ Fishers ➢ People’s Organization http://www.ospo.noaa.gov/Products/ocean/cb/hotspots Marine Emergency Response System (MERSys) (Jacinto et al. -

Sea Urchin Management in Bolinao, Pangasinan, Philippines: Attempts on Sustainable Use of a Communal Resource

Sea urchin management in Bolinao, Pangasinan, Philippines: Attempts on sustainable use of a communal resource Liana T. McManus, Edgardo D. Gomez, John W. McManus, and Antoinette Juinio Marine Science Institute University of the Philippines Diliman, Quezon City 1101 Philippines ABSTRACT The sea urchin, Tripneustes gratilla. is exploited in the reef flats of Bolinao for its roe. A high international demand for brined sea urchin gonads since the early 1980's has led to an overfished resource base. An exploitation level index of 0.6 to 0.7, and slow decline in harvest rates from 1987 to 1989 indicate the extent of overfishing. as of 1988. The adoption of an annual closed collecting season from December to January helped mitigate the status in 1989. Succeeding closed seasons however suffered from lack of effective enforcement. Changing patterns in the manpower structure of the industry from self-employment among fishermen, to one of direct dependence of fishermen on foreign buyers with increasing capital inputs, seem to have exacerbated over-harvest of sea urchins. Although the potential to draw a comprehensive management plan exists within the powers of the municipality of Bolinao, an effective village mobilization program directed at grassroots participation in resource stewardship is the recommended course of action. Introduction The sea urchin industry of Bolinao, Pangasinan, northern Philippines (fig. 1), is a case study of a communal resource which can sustain harvest provided that a comprehensive management intervention is drawn up. Because of an ineffective management measure adopted by the municipal council and because of shifts in the manpower structure of the industry, indices obtained from previous studies and a 4- year monitoring of catch effort statistics from a landing site indicate that sea urchins are an overfished resource, and that total daily harvest is on the down trend. -

Pdf | 262.1 Kb

Region III – A total of 405 families or 1,621 persons in 15 brgys in four (4) municipalities and two (2) cities in the Provinces Pampanga and Zambales have been affected by Typhoon “EMONG” Landslide Occured: Olongapo City – Landslide incidents occurred in four (4) Sitios of Bgry Kalaklan, namely: #92 Brgy Kalaklan, #205 Lower Kalaklan, 14-C Upper Kalaklan and #35 Ati-atihan, Hilltop, Kalaklan Casualty: Dead – 1; Injured – 2; Missing – 1 - One (1) reported dead due to heart attack Jeremy Ambalisa in Guinipanng, Brgy Poblacion, Sta. Cruz, Zambales - Two (2) were injured, namely: Willjo Balaran, 3 y/o of Lower Kalaklan and Perla Balaran 49 y/o of the same brgy - One (1) missing namely, Asley Dualo Mosallina in Bagong Silang, Balanga City Actions Taken: • Olongapo City CDCC Rescue Team advised the residents to evacuate immediately to safer grounds • All school buildings in Olongapo City are being prepared as evacuation centers. Olongapo National High School as the main evacuation center. • Olongapo City Engineering Team conducted clearing operations • Kalaklan BDCC was advised to secure and monitor the area for possible landslide due to heavy rains Stranded Passengers: • 500 to 600 stranded passengers at the Port of Batangas bound for the island provinces of Romblon, Palawan and Masbate • 205 stranded passengers in Calapan Port, Oriental Mindoro due to cancellation of trips Reported Flooded Areas Region II – Bambang, Bagabag & Solano, all of Nueva Vizcaya Status of Lifelines: Power Region I • Pangasinan – Power interruption reported in the -

Mariculture in the Philippines Data Collection Selection

Attitudes Towards Mariculture Among Men and Women in Mariculture Areas in the Philippines Alice Joan G. Ferrer1, Herminia A. Francisco2, Benedict Mark Carmelita3, and Jinky Hopanda3 1 2 3 University of the Philippines Visayas, Economy and Environment Program for Southeast Asia, University of the Philippines Visayas Foundation, Inc. [email protected] MARICULTURE IN THE PHILIPPINES Mariculture or Marine Aquaculture started in the Philippines wayback before the government promoted the mariculture park program in the early 2000. Without legislative framework and enforcement, mariculture development was unregulated leading to inefficient practice and environmental problems such as fish kill. The Mariculture Park Program was introduced by the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR), the fisheries arm of the Philippine government, for efficient and regulated mariculture operation, at the same time provide employment and alternative livelihood to the marginalized fisherfolks. However, the establishment of the fish cages and pens led to issues of displacement of fishers from their traditional fishing ground, and occurrence of water pollution due to organic enrichment resulting from intensive fish culture. Support from the local residents in the mariculture sites in the country is needed to address these issues and improve the policies in promotion of balanced mariculture operation. This research focused on describing the attitude towards mariculture among men and women in the seven mariculture areas in the country that could help improve policies for mariculture operation. SELECTION OF THE STUDY SITES Balingasag in Misamis Oriental Province and Lopez Jaena in Misamis Occidental Province (Region 10-Northern Mindanao) Calape and Talibon in Bohol Province (Region 7-Central Visayas) Sto. -

Pdf | 308.16 Kb

2. Damaged Infrastructure and Agriculture (Tab D) Total Estimated Cost of Damages PhP 411,239,802 Infrastructure PhP 29,213,821.00 Roads & Bridges 24,800,000.00 Transmission Lines 4,413,821.00 Agriculture 382,025,981.00 Crops 61,403,111.00 HVCC 5,060,950.00 Fisheries 313,871,920.00 Facilities 1,690,000.00 No report of damage on school buildings and health facilities as of this time. D. Emergency Incidents Monitored 1. Region II a) On or about 10:00 AM, 08 May 2009, one (1) ferry boat owned by Brgy Captain Nicanor Taguba of Gagabutan, Rizal, bound to Cambabangan, Rizal, Cagayan, to attend patronal fiesta with twelve (12) passengers on board, capsized while crossing the Matalad River. Nine (9) passengers survived while three (3) are still missing identified as Carmen Acasio Anguluan (48 yrs /old), Vladimir Acasio Anguluan (7 yrs /old) and Mac Dave Talay Calibuso (5 yrs/old), all from Gagabutan East Rizal, Cagayan. The 501st Infantry Division (ID) headed by Col. Remegio de Vera, PNP personnel and some volunteers from Rizal, Cagayan conducted search and rescue operations. b) In Nueva Vizcaya, 31 barangays were flooded: Solano (16), Bagabag (5), Bayombong (4), Bambang (4), in Dupax del Norte (1) and in Dupax del Sur (1). c) Barangays San Pedro and Manglad in Maddela, Quirino were isolated due to flooding. e) The low-lying areas of Brgys Mabini and Batal in Santiago City, 2 barangays in Dupax del Norte and 4 barangays in Bambang were rendered underwater with 20 families evacuated at Bgy Mabasa Elementary School. -

Pdf | 314.34 Kb

C. Damages 1. Damaged Houses (Details Tab C) Region Province Totally Partially Total I La Union 2,138 13,032 15,170 Pangasinan 13,881 10,969 24,850 Sub-total 16,019 24,001 40,030 II Isabela 7 7 III Pampanga - 3 3 CAR Benguet 1 1 2 Kalinga 8 6 14 Mt Province 1 2 3 Ifugao 38 123 161 Total 16,074 24,136 40,210 2. Damaged Infrastructure and Agriculture (Details on Tab D) Region Province Infrastructure Agriculture Estimated Cost of Damage (Millions) Region I La Union 19,387,673 22,356,381 41,744,054 Pangasinan 187,966,148 506,734,333 694,700,481 Sub-total 207,353,821 529,090,714 736,444,535 Region II Isabela - 34,290,992 34,290,992 Cagayan 26,686,501 26,686,501 Nueva Vizcaya 731,185 731,185 Quirino 28,700,000 969,140 969,140 Sub-total 28,700,000 62,677,818 91,377,818 Region III Zambales 836,528 836,528 CAR Apayao 7,297,000 7,297,000 Benguet 13,650,000 - 13,650,000 Ifugao 20,300,000 80,453,000 100,753,000 Kalinga 1,000,000 6,697,000 7,697,000 Mt Province 1,345,000 ___________ 1,345,000 Sub-total 36,295,000 94,447,000 130,742,000 TOTAL 272,348,821 687,052,060 959,400,881 II. Humanitarian Efforts A. Extent of the Cost of Assistance • The estimated cost of assistance provided by NDCC, DSWD, LGUs and NGOs and Other GOs in Regions I, II, III, and CAR is PhP6,044,598.46 • Breakdown of assistance per region Regions NDCC DSWD DOH LGUs NGOs/Other GOs Rice Cost CAR 64,600.00 147,600.00 8,000.00 I La Union 300 273,750.00 4,000.00 216,442.00 950 866,875.00 633,270.00 24,280.56 3,349,891.34 Pangasinan II - - - 178,977.75 III - 255,000.00 - 21,912.00 Total 1,250 1,395,625.00 697,870.00 28,280.59 3,914,823.09 8,000.00 2 B. -

Final Report – Bolinao Environmental Monitoring and Modelling of Aquaculture in Risk Areas of the Philippines (EMMA)

9296 Tromsø, Norway Tel. +47 77 75 03 00 Faks +47 77 75 03 01 Rapporttittel /Report title Final report – Bolinao Environmental Monitoring and Modelling of Aquaculture in risk areas of the Philippines (EMMA) Forfatter(e) / Author(s) Akvaplan-niva rapport nr / report no: Patrick White, Akvaplan-niva APN-2415.02 Guttorm N. Christensen, Akvaplan-niva Dato / Date: Rune Palerud, Akvaplan-niva 00/00/00 Tarzan Legovic Antall sider / No. of pages Westly Rosarioo 52 + 0 Nelson Lopez Distribusjon / Distribution Regie Regpala Begrenset/Restricted Suncana Gecek Jocelyn Hernandez Oppdragsgiver / Client Oppdragsg. ref. / Client ref. NIFTDC – BFAR Sammendrag / Summary Draft report of the Emneord: Key words: Philippines Aquaculture Environmental survey Carrying capacity Training Participatory workshops Prosjektleder / Project manager Kvalitetskontroll / Quality control Patrick White Anton Giæver navn navn © 2007 Akvaplan-niva Oppdragsgiveren har lov å kopiere hele rapporten til eget bruk. Det er ikke imidlertid ikke tillatt å kopiere, eller bruke på annen måte, deler av rapporten (tekstutsnitt, figurer, konklusjoner. osv) uten at man på forhånd har fått skriftlig samtykke fra Akvaplan-niva Final report – Bolinao: Environmental Monitoring and Modelling of Aquaculture in risk areas of the Philippines (EMMA) Table of content Final report – Bolinao ................................................................................................................1 Environmental Monitoring and Modelling of Aquaculture in risk areas of the Philippines (EMMA) ....................................................................................................................................1 -

Item Indicators Agno Alaminos Anda Bolinao Bani Burgos

Item Indicators Agno Alaminos Anda Bolinao Bani Burgos Binamaley Dasol Dagupan (City) Infanta Sual Labrador Lingayen San Fabian 1.1 M/C Fisheries Ordinance No Yes Yes yes Yes No yes yes Yes Yes Yes yes yes No 1.2 Ordinance on MCS No yes Yes yes Yes No yes No Yes No No yes yes No 1.3a Allow Entry of CFV No No No No No No No No No No No N/A No No 1.3b Existence of Ordinance N/A N/A N/A No N/A No N/A No No No No No No N/A 1.4a CRM Plan No Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes No No Yes Yes N/A 1.4b ICM Plan No Yes Yes No Yes No Yes Yes Yes No No Yes No N/A 1.4c CWUP No No No No Yes No No No Yes No No Yes No N/A 1.5 Water Delineation No Yes Yes No No No No Yes Yes No No N/A No N/A 1.6a Registration of fisherfolk Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.6b List of org/coop/NGOs Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes 1.7a Registration of Boats Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.7b Licensing of Boats Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.7c Fees for Use of Boats Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes No No No 1.8a Licensing of Gears No Yes Yes Yes Yes No No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No 1.8b Fees for Use of Gears No Yes Yes Yes Yes No No Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes No 1.9a Auxiliary Invoices No Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No 1.9b Monthly Summary Report No No No Yes No No Yes No No No Yes No Yes No 1.10a Fish Landing Site Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.10b Fish Ports N/A No Yes Yes No No Yes No No No No No Yes No 1.10c Ice Plants N/A No No -

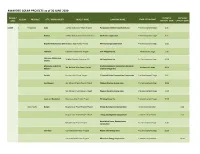

AWARDED SOLAR PROJECTS As of 30 JUNE 2020

AWARDED SOLAR PROJECTS as of 30 JUNE 2020 . ISLAND / POTENTIAL INSTALLED REGION PROVINCE CITY / MUNICIPALITY PROJECT NAME COMPANY NAME STAGE OF CONTRACT GRID CAPACITY (MW) CAPACITY (MW) LUZON I Pangasinan Anda 1 MWp Anda Solar Power Project Pangasinan I Electric Cooperative, Inc. Pre-Development Stage 0.00 Bolinao 5 MWp Bolinao Solar PV Power Plant EEI Power Corporation Pre-Development Stage 5.00 Bugallon & San Carlos City Bugallon Solar Power Project Phinma Energy Corporation Pre-Development Stage 1.03 Labrador Labrador Solar Power Project IJG1 Philippines Inc. Development Stage 5.00 Labrador, Mabini and 90 MW Cayanga- Bugallon SPP PV Sinag Power Inc. Pre-Development Stage 90.00 Infanta Mapandan and Santa OneManaoag Solar Corporation (Formerly Sta. Barbara Solar Power Project Development Stage 10.14 Barbara SunAsia Energy Inc.) Rosales Rosales Solar Power Project C Squared Prime Commodities Corporation Pre-Development Stage 0.00 San Manuel San Manuel 2 Solar Power Project Pilipinas Einstein Energy Corp. Pre-Development Stage 70.00 San Manuel 1 Solar Power Project Pilipinas Newton Energy Corp. Pre-Development Stage 70.00 Sison and Binalonan Binalonan Solar Power Project PV Sinag Power Inc. Pre-Development Stage 50.00 Ilocos Norte Burgos Burgos Solar Power Project Phase I Energy Development Corporation Commercial Operation 4.10 Burgos Solar Power Project Phase 2 Energy Development Corporation Commercial Operation 2.66 NorthWind Power Development Bangui Solar Power Project Pre-Development Stage 2.50 Corporation Currimao Currimao Solar Power Project. Nuevo Solar Energy Corp. Pre-Development Stage 50.00 Currimao Solar Power Project.. Mirae Asia Energy Corporation Commercial Operation 20.00 . -

Coral Reef Restoration (Bolinao, Philippines) in the Face of Frequent Natural Catastrophes

SET-BACKS AND SURPRISES Coral Reef Restoration (Bolinao, Philippines) in the Face of Frequent Natural Catastrophes Lee Shaish,1,2,3 Gideon Levy,1,2 Gadi Katzir,4 and Baruch Rinkevich1 Abstract nursery and transplanted corals. This study analyzes the effects of these natural catastrophes on restoration efforts, Restoration of coral reefs is generally studied under the and presents the successes and failures of recently used most favorable of environmental conditions, a stipulation restoration instruments. Our results show that (1) in the that does not always reflect situations in the field. A 2-year nursery phase, consideration should be paid to depth- study (2005–2007), employing the “reef gardening” res- flexible constructions and tenable species/genotypes priori- toration concept (that includes nursery and transplanta- tization and (2) for transplantation acts, site/species delib- tion phases), was conducted in Bolinao, Philippines, in eration, timing, and specific site selections should be taken an area suffering from intense human stressors. This site into account. Only the establishment of large-scale nurs- also experienced severe weather conditions, including a eries and large transplantation measures and the adapting forceful southwesterly monsoon season and three stochas- of restoration management to the frequently changing envi- tic environmental events: (1) a category 4 typhoon hit ronment may forestall extensive reef degradation due to the the Bolinao’s lagoon (May 2006) impacted farmed corals; combination of continuous anthropogenic and worsening (2) heavy rains (August 2006) caused seepages of fresh- global changes. water, followed by reduced salinity that impacted trans- planted colonies; and (3) a bleaching event (June 2007) Key words: coral, climate change, gardening concept, caused by warming of seawater, severely impacted both Philippines, restoration. -

Ethnobotanical Study of Traditional Medicinal Plants Used by Indigenous Sambal-Bolinao of Pangasinan, Philippines

PSU Journal of Natural and Allied Sciences Vol. 1 No.1, pp. 52-63, December 2017 Ethnobotanical Study of Traditional Medicinal Plants Used By Indigenous Sambal-Bolinao of Pangasinan, Philippines W. T. Fajardo1, L.T. Cancino1, E.B. Dudang1, I.A. De Vera2, R. M. Pambid3, A. D.Junio4 1aFaculty of Natural Science Department, Pangasinan State University-Lingayen Campus, Lingayen, 2401, Pangasinan, Philippines 2Faculty of Natural Science Department, Pangasinan State University-Binmaley Campus, Binmaley 2417, Pangasinan, Philippines 3Faculty of Natural Science Department, Pangasinan State University-BayambangCampus, Bayambang, 2423, Pangasinan, Philippines Weenalei T. Fajardo Natural Science Department, Science Laboratory Building, Pangasinan State University, Lingayen Campus, Alvear West, Lingayen, Pangasinan, 2401 Email: [email protected] Abstract — Traditional knowledge of medicinal plants and their uses by indigenous peoples are not only significant for conservation of biodiversity and cultural traditions but also for communal healthcare and drug development in the present and future. The Philippines is one of the world’s 17 mega-biodiverse countries which collectively claim two-thirds of the earth’s biological diversity within its boundaries. Thus, the country has high potential for the development of its own alternative medicines specifically those plant derived sources. One of its largest provinces is Pangasinan wherein its people is considered as the ninth largest Filipino ethnic group. Furthermore, it is labelled as one melting pots of mixed-cultures in the country. Its western part has two towns having their distinct dialect-Bolinao which are found in the towns of Anda and Bolinao only. They were claimed initially to be highly superstitious and worshiped the spirits of their ancestors. -

Region Name of Laboratory I A.G.S. Diagnostic and Drug

REGION NAME OF LABORATORY I A.G.S. DIAGNOSTIC AND DRUG TESTING LABORATORY I ACCU HEALTH DIAGNOSTICS I ADH-LENZ DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY I AGOO FAMILY HOSPITAL I AGOO LA UNION MEDICAL DIAGNOSTIC CENTER, INC. I AGOO MEDICAL CLINICAL LABORATORY I AGOO MUNICIPAL HEALTH OFFICE CLINICAL LABORATORY I ALAMINOS CITY HEALTH OFFICE LABORATORY I ALAMINOS DOCTORS HOSPITAL, INC. I ALCALA MUNICIPAL HEALTH OFFICE LABORATORY I ALLIANCE DIAGNOSTIC CENTER I APELLANES ADULT AND PEDIATRIC CLINIC & LABORATORY I ARINGAY MEDICAL DIAGNOSTIC CENTER I ASINGAN DIAGNOSTIC CLINIC I ATIGA MATERNITY AND DIAGNOSTIC CENTER I BACNOTAN DISTRICT HOSPITAL I BALAOAN DISTRICT HOSPITAL I BANGUI DISTRICT HOSPITAL I BANI - RHU CLINICAL LABORATORY I BASISTA RURAL HEALTH UNIT LABORATORY I BAUANG MEDICAL AND DIAGNOSTIC CENTER I BAYAMBANG DISTRICT HOSPITAL I BETHANY HOSPITAL, INC. I BETTER LIFE MEDICAL CLINIC I BIO-RAD DIAGNOSTIC CENTER I BIOTECHNICA DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORY I BLESSED FAMILY DOCTORS GENERAL HOSPITAL I BLOODCARE CLINICAL LABORATORY I BOLINAO COMMUNITY HOSPITAL I BUMANGLAG SPECIALTY HOSPITAL (with Additional Analyte) I BURGOS MEDICAL DIAGNOSTIC CENTER CO. I C & H MEDICAL AND SURGICAL CLINIC, INC. I CABA DISTRICT HOSPITAL I CALASIAO DIAGNOSTIC CENTER I CALASIAO MUNICIPAL CLINICAL LABORATORY I CANDON - ST. MARTIN DE PORRES HOSPITAL (REGIONAL) I CANDON GENERAL HOSPITAL (ILOCOS SUR MEDICAL CENTER, INC.) REGION NAME OF LABORATORY I CANDON ST. MARTIN DE PORRES HOSPITAL I CARDIO WELLNESS LABORATORY AND DIAGNOSTIC CENTER I CHRIST-BEARER CLINICAL LABORATORY I CICOSAT HOSPITAL I CIPRIANA COQUIA MEMORIAL DIALYSIS AND KIDNEY CENTER, INC. I CITY GOVERNMENT OF BATAC CLINICAL LABORATORY I CITY OF CANDON HOSPITAL I CLINICA DE ARCHANGEL RAFAEL DEL ESPIRITU SANTO AND LABORATORY I CLINIPATH MEDICAL LABORATORY I CORDERO - DE ASIS CLINIC X-RAY & LABORATORY I CORPUZ CLINIC AND HOSPITAL I CUISON HOSPITAL, INC.