GEMCA : Papers in Progress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lurking in the Shadows: Wide-Separation Gas Giants As Tracers of Planet Formation

Lurking in the Shadows: Wide-Separation Gas Giants as Tracers of Planet Formation Thesis by Marta Levesque Bryan In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Pasadena, California 2018 Defended May 1, 2018 ii © 2018 Marta Levesque Bryan ORCID: [0000-0002-6076-5967] All rights reserved iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I would like to thank Heather Knutson, who I had the great privilege of working with as my thesis advisor. Her encouragement, guidance, and perspective helped me navigate many a challenging problem, and my conversations with her were a consistent source of positivity and learning throughout my time at Caltech. I leave graduate school a better scientist and person for having her as a role model. Heather fostered a wonderfully positive and supportive environment for her students, giving us the space to explore and grow - I could not have asked for a better advisor or research experience. I would also like to thank Konstantin Batygin for enthusiastic and illuminating discussions that always left me more excited to explore the result at hand. Thank you as well to Dimitri Mawet for providing both expertise and contagious optimism for some of my latest direct imaging endeavors. Thank you to the rest of my thesis committee, namely Geoff Blake, Evan Kirby, and Chuck Steidel for their support, helpful conversations, and insightful questions. I am grateful to have had the opportunity to collaborate with Brendan Bowler. His talk at Caltech my second year of graduate school introduced me to an unexpected population of massive wide-separation planetary-mass companions, and lead to a long-running collaboration from which several of my thesis projects were born. -

Sacred Image, Civic Spectacle, and Ritual Space: Tivoli’S Inchinata Procession and Icons in Urban Liturgical Theater in Late Medieval Italy

SACRED IMAGE, CIVIC SPECTACLE, AND RITUAL SPACE: TIVOLI’S INCHINATA PROCESSION AND ICONS IN URBAN LITURGICAL THEATER IN LATE MEDIEVAL ITALY by Rebekah Perry BA, Brigham Young University, 1996 MA, University of Massachusetts Amherst, 2006 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts & Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2011 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts & Sciences This dissertation was presented by Rebekah Perry It was defended on October 28, 2011 and approved by Franklin Toker, Professor, History of Art and Architecture Anne Weis, Professor, History of Art and Architecture Bruce Venarde, Professor, History Alison Stones, Professor, History of Art and Architecture ii Copyright © by Rebekah Perry 2011 iii SACRED IMAGE, CIVIC SPECTACLE, AND RITUAL SPACE: TIVOLI’S INCHINATA PROCESSION AND ICONS IN URBAN LITURGICAL THEATER IN LATE MEDIEVAL ITALY Rebekah Perry, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2011 This dissertation examines the socio-politics of urban performance and ceremonial imagery in the nascent independent communes of late medieval Lazio. It explores the complex manner in which these central Italian cities both emulated and rejected the political and cultural hegemony of Rome through the ideological and performative reinvention of its cult icons. In the twelfth century the powerful urban center of Tivoli adopted Rome’s grandest annual public event, the nocturnal Assumption procession of August 14-15, and transformed it into a potent civic expression that incorporated all sectors of the social fabric. Tivoli’s cult of the Trittico del Salvatore and the Inchinata procession in which the icon of the enthroned Christ was carried at the feast of the Assumption and made to perform in symbolic liturgical ceremonies were both modeled on Roman, papal exemplars. -

M-001 Macrobius, Aurelius Theodosius in Somnium Scipionis

M r M-001 Macrobius, AureliusTheodosius h4 Macrobius, AureliusTheodosius: Saturnalia. In somnium Scipionis expositio, et al. refs. Macr. r Brescia: Boninus de Boninis, de Ragusia, 6 June 1483. Folio. [a2 ] Cicero, Marcus Tullius: Somnium Scipionis: De republica 10 8 6 8 6 8 6 8 6 8 6 8 [extract]. collation: a b c d e^g h i k l^n o q^u x y & m a A^C . Leaf a2 signed a, a3 signed aii, etc. refs. Cic. Rep. 6. 9^29; Macrobius, Commentarii in somnium v Scipionis, ed. James Willis (Leipzig, 1963),155^63. Woodcut diagrams, and, on f8 , a map of the world, for which see v Campbell. [a4 ] Macrobius, Aurelius Theodosius: In somnium Scipionis expositio. HC *10427; Go¡ M-9; BMC VII 968; Pr 6953; BSB-Ink M-2; refs. Macrobius, Commentarii in somnium Scipionis, ed. Willis, Campbell, Maps, 879(i); CIBN M-7; Sander 4072; Sheppard 1^154. 5750. Micro¢che: Unit 3: Image of the World: Geography and r Cosmography. [f5 ] Macrobius, AureliusTheodosius: Saturnalia. refs. Macr. COPY Venice: Nicolaus Jenson, 1472. Folio. Wanting the blank leaf a1. collation: [a b10 c^m8 n10 o^v8]. Leaf a10 bound after b8. Binding: Eighteenth/nineteenth-century gold-tooled diced rus- HCR 10426; Go¡ M-8; BMC V 172; Pr 4085; BSB-Ink M-1; CIBN sia; gilt-edged leaves, marbled pastedowns; the gold stamp of the M-6; Hillard 1268; Lowry, Jenson, 242, no. 27; Rhodes 1135; Bodleian Library on both covers. Size: 312 ¿ 222 ¿ 37 mm. Sizeof Sheppard 3258. leaf: 300 ¿ 203 mm. -

Does Magnetic Field Impact Tidal Dynamics Inside the Convective

A&A 631, A111 (2019) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201936477 & c A. Astoul et al. 2019 Astrophysics Does magnetic field impact tidal dynamics inside the convective zone of low-mass stars along their evolution? A. Astoul1, S. Mathis1, C. Baruteau2, F. Gallet3, A. Strugarek1, K. C. Augustson1, A. S. Brun1, and E. Bolmont4 1 AIM, CEA, CNRS, Université Paris-Saclay, Université Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cité, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 IRAP, Observatoire Midi-Pyrénées, Université de Toulouse, 14 avenue Edouard Belin, 31400 Toulouse, France 3 Univ. Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG, 38000 Grenoble, France 4 Observatoire de Genève, Université de Genève, 51 chemin des Maillettes, 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland Received 7 August 2019 / Accepted 21 September 2019 ABSTRACT Context. The dissipation of the kinetic energy of wave-like tidal flows within the convective envelope of low-mass stars is one of the key physical mechanisms that shapes the orbital and rotational dynamics of short-period exoplanetary systems. Although low-mass stars are magnetically active objects, the question of how the star’s magnetic field impacts large-scale tidal flows and the excitation, propagation and dissipation of tidal waves still remains open. Aims. Our goal is to investigate the impact of stellar magnetism on the forcing of tidal waves, and their propagation and dissipation in the convective envelope of low-mass stars as they evolve. Methods. We have estimated the amplitude of the magnetic contribution to the forcing and dissipation of tidally induced magneto- inertial waves throughout the structural and rotational evolution of low-mass stars (from M to F-type). -

Manili Astronomicon Liber II

>^ B^'^i. LIBRARY OF THE University of California. 7 ^^1 ni Class MANILI ASTRONOMICON LIBER II EDIDIT H. W. GARROD COLLEGII MERTONENSIS SOCIVS OXONII E TYPOGRAPHEO ACADEMICO M DCCCC XI HENRY FROWDE PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD LONDON, EDINBURGH, NEW YORK TORONTO AND MELBOURNE ROBINSONI ELLIS VIRO DE POETIS ASTRONOMICIS INSIGNITE MERITO ET 'NOSTRAE MVLTVM QVI PROFVIT VRBI' 226340 : PREFACE The second book of the Astronomica is at once the longest and the most difficult. In this book Manilius passes from the popular astronomy with which he is occupied in Book I to the proper business of the maike- maticus—to an astrology based on geometrical and arith- metical calculations. He passes, that is, from a subject moderately diverting to one difficult and repellent. Many students of Latin poetry make their way through the first book. A moderate scholar can understand it, and it has recently been well edited. But few, probably, of those who read the first achieve also the second book. The ' — signorum lucentes undique flammae ', the aa-rpcuv ofiriyvpis all that is picturesque and inviting. But when we come on to triangles, quadrangles, hexagons, dodecatemories, and the dodecatemories of dodecatemories—then our faith in a Providence which has made the beautiful so hard begins to fail us. And not only is the second book hard, but the commentaries upon it are hard too. No one commentary suffices ; and even when he has all the com- mentaries before him, the student will still be in want of a means of approach to them—for none of them furnishes a real Introduction to Manilius. -

Photometry Using Mid-Sized Nanosatellites

Feasibility-Study for Space-Based Transit Photometry using Mid-sized Nanosatellites by Rachel Bowens-Rubin Submitted to the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Science at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2012 @ Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2012. All rights reserved. A uthor .. ............... ................ Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Science May 18, 2012 C ertified by .................. ........ ........................... Sara Seager Professor, Departments of Physics and EAPS Thesis Supervisor VIZ ~ Accepted by.......,.... Robert D. van der Hilst Schulumberger Professor of Geosciences and Head, Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Science 2 Feasibility-Study for Space-Based Transit Photometry using Mid-sized Nanosatellites by Rachel Bowens-Rubin Submitted to the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Science on May 18, 2012, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Science Abstract The photometric precision needed to measure a transit of small planets cannot be achieved by taking observations from the ground, so observations must be made from space. Mid-sized nanosatellites can provide a low-cost option for building an optical system to take these observations. The potential of using nanosatellites of varying sizes to perform transit measurements was evaluated using a theoretical noise budget, simulated exoplanet-transit data, and case studies to determine the expected results of a radial velocity followup mission and transit survey mission. Optical systems on larger mid-sized nanosatellites (such as ESPA satellites) have greater potential than smaller mid-sized nanosatellites (such as CubeSats) to detect smaller planets, detect planets around dimmer stars, and discover more transits in RV followup missions. -

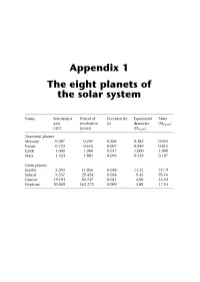

Appendix 1 the Eight Planets of the Solar System

Appendix 1 The eight planets of the solar system Name Semimajor Period of Eccentricity Equatorial Mass axis revolution ie) diameter (MEarth) (AU) (years) (DEarth) Terrestrial planets Mercury 0.387 0.241 0.206 0.382 0.055 Venus 0.723 0.615 0.007 0.949 0.815 Earth 1.000 1.000 0.017 1.000 1.000 Mars 1.524 1.881 0.093 0.532 0.107 Giant planets Jupiter 5.203 11.856 0.048 11.21 317.9 Saturn 9.537 29.424 0.054 9.45 95.16 Uranus 19.191 83.747 0.047 4.00 14.53 Neptune 30.069 163.273 0.009 3.88 17.14 Appendix 2 The first 200 extrasolar planets Name Mass Period Semimajor axis Eccentricity (Mj) (years) (AU) (e) 14 Her b 4.74 1,796.4 2.8 0.338 16 Cyg B b 1.69 798.938 1.67 0.67 2M1207 b 5 46 47 Uma b 2.54 1,089 2.09 0.061 47 Uma c 0.79 2,594 3.79 0 51 Pegb 0.468 4.23077 0.052 0 55 Cnc b 0.784 14.67 0.115 0.0197 55 Cnc c 0.217 43.93 0.24 0.44 55 Cnc d 3.92 4,517.4 5.257 0.327 55 Cnc e 0.045 2.81 0.038 0.174 70 Vir b 7.44 116.689 0.48 0.4 AB Pic b 13.5 275 BD-10 3166 b 0.48 3.488 0.046 0.07 8 Eridani b 0.86 2,502.1 3.3 0.608 y Cephei b 1.59 902.26 2.03 0.2 GJ 3021 b 3.32 133.82 0.49 0.505 GJ 436 b 0.067 2.644963 0.0278 0.207 Gl 581 b 0.056 5.366 0.041 0 G186b 4.01 15.766 0.11 0.046 Gliese 876 b 1.935 60.94 0.20783 0.0249 Gliese 876 c 0.56 30.1 0.13 0.27 Gliese 876 d 0.023 1.93776 0.0208067 0 GQ Lup b 21.5 103 HD 101930 b 0.3 70.46 0.302 0.11 HD 102117 b 0.14 20.67 0.149 0.06 HD 102195 b 0.488 4.11434 0.049 0.06 HD 104985 b 6.3 198.2 0.78 0.03 1 70 The first 200 extrasolar planets Name Mass Period Semimajor axis Eccentricity (Mj) (years) (AU) (e) HD 106252 -

Radial Velocity

Radial Velocity Christophe Lovis Universite´ de Geneve` Debra A. Fischer Yale University The radial velocity technique was utilized to make the first exoplanet discoveries and continues to play a major role in the discovery and characterization of exoplanetary systems. In this chapter we describe how the technique works, and the current precision and limitations. We then review its major successes in the field of exoplanets. With more than 250 planet detections, it is the most prolific technique to date and has led to many milestone discoveries, such as hot Jupiters, multi-planet systems, transiting planets around bright stars, the planet-metallicity correlation, planets around M dwarfs and intermediate-mass stars, and recently, the emergence of a population of low-mass planets: ice giants and super-Earths. In the near future radial velocities are expected to systematically explore the domain of telluric and icy planets down to a few Earth masses close to the habitable zone of their parent star. They will also be used to provide the necessary follow-up observations of transiting candidates detected by space missions. Finally, we also note alternative radial velocity techniques that may play an important role in the future. 1. INTRODUCTION shifts with resepct to telluric lines. Assuming that telluric lines are at rest relative to the spectrometer, these absorp- Since the end of the XIXth century, radial velocities have tion lines would trace the stellar light path and illuminate been at the heart of many developments and advances in as- the optics in the same way and at the same time as the star. -

P-001 Paganellus Prignanus, Bartholomaeus De Imperio

P P-001 Paganellus Prignanus, Bartholomaeus canant alii sortitum regna tonantem > Moxque gigantea bella De imperio Cupidinis. parata manu'. f v [Verse.] `Inuidiae saeuo securi a dente libelli Ibitis haec nun- v 3 > a1 P[aganellus] Prignanus, B[artholomaeus]: `Epigramma' quam rodere parua solet'; 2 elegiac distichs. [addressed to the books].`Ibitis inculti? Celsas ne audebitis aulas Modena: Dominicus Rocociolus, 7 Oct. 1489. 4o. Intrare? Aut doctas peruolitare manus?'; 16 lines of verse. 8 4 r> collation: a^e f . a2 [Summary of the contents of the three books.] Incipit: `Quanquam opus hoc de imperio Cupidinis inscribitur non HC 12262; C 4577; Go¡ P-5; BMC VII 1062; Pr 7195; CIBN P-2; tamen . .' Hillard 1506; Sheppard 5971. r a3 Paganellus Prignanus, Bartholomaeus: De imperio Cupidinis COPY [addressed to] Alfonsus I d'Este, 3rd Duke of Ferrara and Bound with O-003; see there for details of binding, decoration, and provenance. Size of leaf: 198 ¿ 136 mm. Modena.`[I]mperium et uires et saeua Cupidinis arma > Miraque sopito pectore uisa canam'; elegiac distichs. `Nota' marks, pointing hands, and underlining are supplied in r g4 [Paganellus Prignanus, Bartholomaeus: Verse addressed to the black ink. reader, asking forgiveness for errors.] `Si quid in his libris erras- shelfmark: Inc. e. X1(2). sem, candide lector > Da ueniam ignauus pectore somnus erat'; 1 elegiac distich. P-003 Palladius Soranus, Domitius Modena: Dominicus Rocociolus, 23 May 1492. 4o. Erroneously entered in H under Paiellus. Pr dates to 1498. Epigrammata et elegiae. 8 4 r collation: a^f g . a1 [Title-page.] `Domici Palladii Sorani Epigrammaton libelli, H *12267; C 4579; Go¡ P-6; BMC VII 1063; Pr 7202; BSB-Ink P-3; Libellus elegiarum, Genethliacon urbis Romae, In Locutuleium'. -

Prudentius, with an English Translation by H.J. Thomson

THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY FOUNDED BY JAMES LOEB, IX.D. ^^ .-. ,- / ^- EDITED BY tT. E. PAGE, C.H., LITT.D. E. CAPPS, PH.D., IX.D. W. H. D. ROUSE, litt.d. L. A. POST, M.A. E. H. WARinNGTOX, M.A., F.K.HIST.SOC. PRUDENTIUS I y-n- PRUDEI x^IUS WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY H. J. THOMSON, D.LiTT. LATE PBOFESSOR OF LATIX IS THE inaVERSITT COLLEGE OP XOBTH WALE3, BASGOK Un two volumes I 499010 LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS MOMXLIX Printed in Great Britain (o(oLp'S V.l CONTENTS PACK IXTRODXTCnON vii PBAEFATIO ........ 2 ^ LIBEB CATHEMEBIXO?T 6 APOTHEOSIS 116 HAMABTIGENIA . 200 KYCHOMACHIA 274 COSTBA OKATIONEM SYMMACHI, LIBEB I . 344 INTRODUCTION AuRELius Prude:itius Clemens, like a number of eminent Latin ^Titers of the classical age, was bom in Spain; unlike them, although he visited Rome, he appears to have hved and Avorked in his native land.** In the prefatory verses which, in his fifty- seventh year, he WTote for an edition of his poems,* he indicates (at line 24) that he was born in the consulship of SaUa, that is, in the year 348 . He does not name his birth-place, and there is no con- clusive evidence to determine it ; but his oaati words associate his life with the north-eastern part of Spain, and on such evidence as we have it seems •liost likely that he was born at Caesaraugusta Saragossa)/ From the fact that, while he laments an ill-spent youth, he does not accuse himself of paganism or speak of ha\-ing been converted, it is inferred that his parents were Christians. -

Large Radial Velocity Searches and Chemical Abundance Studies

LARGE RADIAL VELOCITY SEARCHES AND CHEMICAL ABUNDANCE STUDIES OF EXOPLANET-HOSTING STARS By Claude E. Mack III Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Physics May, 2015 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Dr. Keivan G. Stassun, Ph.D. Dr. Simon C. Schuler, Ph.D. Dr. Kelly Holley-Bockelmann, Ph.D. Dr. Andreas Berlind, Ph.D. Dr. David A. Weintraub, Ph.D. Dr. David Ernst, Ph.D. To my parents, Stella and Claude, and to their parents, Narcelia and James, Edith and Claude, for the heritage of education and a thirst for knowledge that they have passed down to me. ii Table of Contents Page List of Tables ...................................... vi List of Figures ..................................... vii Chapter I. Introduction ................................... 1 II. HowanSB2canappeartobeastar+BDsystem . .. 4 2.1. Abstract................................. 4 2.2. Introduction............................... 5 2.3. ObservationsandDataProcessing . 10 2.3.1. SDSS-III MARVELS Discovery RV Data . 10 2.3.2. APO-3.5m/ARCESRVData . 12 2.3.3. HET/HRSRVData ..................... 16 2.3.3.1. CCFMask ...................... 16 2.3.3.2. TODCOR....................... 18 2.3.4. FastCamLuckyImaging . 19 2.3.5. KeckAOImaging....................... 20 2.4. Results ................................. 21 2.4.1. Initial spurious solution: a BD companion to a solar-type star............................... 21 2.4.2. Final solution: A highly eccentric, double-lined spectro- scopicbinary ......................... 27 2.4.2.1. RVfitting....................... 28 2.4.2.2. Determining the stellar parameters for TYC 3010 . 30 2.4.3. Inferred evolutionary status of TYC 3010 . 36 2.5. Discussion................................ 37 2.5.1.