Tasmin Little: Playing Great Music in Unexpected Locations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer Courses for Kids & Teens

Sparkling 22nd season for Proms MICHAEL ELEFTHERIADES Other free lunchtime concerts The Henrietta Barnett School is NIGEL SUTTON were a delight from first to last. much appreciated. Of special note were prize-winning This year’s programme of harpists Klara Woskowiak and walks was well attended, including Elizabeth Bass; young musicians exploration of the Suburb itself Adi Tal on cello and Nadav to hidden architectural treasures Hertzka on piano; and the in the City of London. organ recital by Tom Winpenny GOOD CAUSES in The Free Church. As ever, the many volunteers PRICELESS that make Proms so special did The Literary Festival weekend outstanding work, from providing also offered priceless moments, home-baked cakes for the LitFest including a conversation between Cafe and pouring Pimm’s in the Phyllida Law and Piers Plowright, refreshments marquee to shifting with the author effortlessly furniture, stewarding and Little Wolf Gang’s musical storytelling enthralled its audience charming all present. Itamar general organisation. Tasmin Little and Piers Lane Srulovich and Sarit Packer of Proms at St Jude’s raises The weather turned a kindly face and drama, she returned to the Honey & Co made everyone eager money for two causes that Spring Wordsearch on Proms, with (mostly) sunny stage in a glorious Union Jack to learn Middle Eastern cookery touch many lives, Toynbee days and balmy evenings filled evening gown, bringing the and delighted the audience with Hall’s ASPIRE programme and winner with music, talks, walks and fun audience to its feet as her rich free samples of cake! the North London Hospice. -

Summer Festival of Chamber Music

Summer Festival of Chamber Music Paxton House, Scottish Borders Friday 19 – Sunday 28 July 2019 Welcome to Music at Paxton Fri 19 July, 7pm · 15 mins Fri 19 July, 7.30pm · 2 hrs /MusicatPaxton Picture Gallery, Paxton House Picture Gallery, Paxton House Festival 2019! #MaP2019 — — Festival Introductory Talk Paul Lewis Piano Angus Smith, — We are delighted that so many outstanding musicians have Music At Paxton Artistic Director Haydn Piano Sonata in E minor, agreed to come to Paxton House this summer, bringing with — Hob. XVI:34 them varied programmes of wonderful music that offer many In this brief festival curtain-raiser, Angus Brahms Three Intermezzi for captivating and entertaining experiences. Smith will shed light on the process of Piano, Op. 117 assembling the 2019 festival, revealing Beethoven Seven Bagatelles, Op. 33 It is a particular pleasure to announce that the prodigiously some of the surprising stories that lie Haydn Piano Sonata in E flat, gifted and engaging Maxwell String Quartet is to be Music behind the choices of composers and Hob. XVI:52 at Paxton’s Associate Ensemble for 2019–21. This young Scottish group is pieces. making great and rapid strides internationally, delighting audiences and critics Paul Lewis is regarded as one of the on their maiden tour of the USA earlier this year. They will present a variety of FREE EVENT to opening concert ticket holders leading pianists of his generation and concerts and community activities for us during their residency, and we also one of the world’s foremost interpreters invite you to meet the players during the Festival – before, during and after Please note that the duration of of central European classical repertoire. -

Menuhin Competition Returns to London in 2016 in Celebration of Yehudi Menuhin's Centenary

Menuhin Competition returns to London in 2016 in celebration of Yehudi Menuhin's Centenary 7-17 April 2016 The Menuhin Competition - the world’s leading competition for violinists under the age of 22 – announces its return to London in 2016 in celebration of Yehudi Menuhin’s centenary. Founded by Yehudi Menuhin in 1983 and taking place in a different international city every two years, the Competition returns to London in 2016 after first being held there in 2004. The centenary event will take place in partnership with some of the UK’s leading music organisations: the Royal Academy of Music, the Philharmonia Orchestra, Southbank Centre, the Yehudi Menuhin School and the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain. It will be presented in association with the BBC Concert Orchestra and BBC Radio 3 which will broadcast the major concerts. Yehudi Menuhin lived much of his life in Britain, and his legacy - not just as one of the greatest violinists of the 20th century, but as an ambassador for music education - is the focus of all the Competition’s programming. More festival of music and cultural exchange than mere competition, the Menuhin Competition in 2016 will be a rich ten-day programme of concerts, masterclasses, talks and participatory activities with world-class performances from candidates and jury members alike. Competition rounds take place at the Royal Academy of Music, with concerts held at London’s Southbank Centre. 2016 jury members include previous winners who have gone on to become world class soloists: Tasmin Little OBE, Julia Fischer and Ray Chen. Duncan Greenland, Chairman of the Menuhin Competition comments: “We are delighted to be bringing the Competition to London in Menuhin’s centenary year and working with such prestigious partners. -

St Valentine's Day 2018

ST VALENTINE’S DAY 2018 Mansion House With Special Guest HUGH LAURIE CMF Team Dr Clare Taylor Managing Director Tabitha McGrath Artist Manager Philip Barrett Executive Assistant Trustees Sir Mark Boleat Sir Roger Gifford Sir Nicholas Kenyon Sir Andrew Parmley Advisory Board Guy Harvey Partner, Shepherd and Wedderburn Wim Hautekiet Managing Director, JP Morgan Alastair King Chairman, Naisbitt King Asset Management Kathryn McDowell CBE Managing Director, London Symphony Orchestra Lizzie Ridding Board Member, City Music Foundation Ian Ritchie Artistic Director and Music Curator, Setubal Music Festival Seb Scotney Editor, London Jazz News Philip Spencer Development Consultant Adrian Waddingham CBE Partner, Barnett Waddingham St Valentine’s Day 2018 2 WELCOME Welcome to the Mansion House and to a celebration of all that is good about life! Not least the wonderful music we are going to hear in the splendour of the greatest surviving Georgian town palace in London. The City Music Foundation – CMF – is just five years old and it was created in this house. Its mission is to turn talent into success by giving training in the “business of music” to soloists and ensembles at the start of their professional careers, as well as promoting them extensively in a modern and professional manner. Several - the Gildas Quartet, Michael Foyle, and Giacomo Smith with the Kansas Smitty’s, are playing for us this evening. This year CMF hopes to move into a more permanent home in the City at St Bartholomew the Less, within the boundaries of St Bartholomew’s Hospital – and within the City of London’s ‘Culture Mile’. This anticipates the relocation of the Museum of London to its new site in Smithfield and the creation of a new Centre for Music on the south side of the Barbican – all exciting developments in the heart of the Capital. -

Download the Concert Programme (PDF)

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Thursday 18 May 2017 7.30pm Barbican Hall Vaughan Williams Five Variants of Dives and Lazarus Brahms Double Concerto INTERVAL Holst The Planets – Suite Sir Mark Elder conductor Roman Simovic violin Tim Hugh cello Ladies of the London Symphony Chorus London’s Symphony Orchestra Simon Halsey chorus director Concert finishes approx 9.45pm Supported by Baker McKenzie 2 Welcome 18 May 2017 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief Welcome to tonight’s LSO concert at the Barbican. BMW LSO OPEN AIR CLASSICS 2017 This evening we are joined by Sir Mark Elder for the second of two concerts this season, as he conducts The London Symphony Orchestra, in partnership with a programme of Vaughan Williams, Brahms and Holst. BMW and conducted by Valery Gergiev, performs an all-Rachmaninov programme in London’s Trafalgar It is always a great pleasure to see the musicians Square this Sunday 21 May, the sixth concert in of the LSO appear as soloists with the Orchestra. the Orchestra’s annual BMW LSO Open Air Classics Tonight, after Vaughan Williams’ Five Variants of series, free and open to all. Dives and Lazarus, the LSO’s Leader Roman Simovic and Principal Cello Tim Hugh take centre stage for lso.co.uk/openair Brahms’ Double Concerto. We conclude the concert with Holst’s much-loved LSO WIND ENSEMBLE ON LSO LIVE The Planets, for which we welcome the London Symphony Chorus and Choral Director Simon Halsey. The new recording of Mozart’s Serenade No 10 The LSO premiered the complete suite of The Planets for Wind Instruments (‘Gran Partita’) by the LSO Wind in 1920, and we are thrilled that the 2002 recording Ensemble is now available on LSO Live. -

Print Version

Tasmin Little On 10th March 2006, The Independent newspaper wrote “Tasmin Little was ideal to represent the Menuhin School's alumni. She is a true successor: international star, enthusiastic chamber player, and now conducting, too”. Biography In addition to a flourishing career as violin soloist which has taken her to every continent of the world, Tasmin Little has further established her reputation as Artistic Director of two Festivals: in 2006 her hugely successful “Delius Inspired” Festival was broadcast for a week on BBC Radio 3 in July. An exciting range of events, ranging from orchestral concerts and chamber music to films and exhibitions, also reached 800 school children in an ambitious programme designed to widen interest in classical music for young people. In 2008 she begins her first year as Artistic Director of the annual Orchestra of the Swan “Spring Sounds” Festival, which this year will feature two world premieres alongside firm favourites in the English and American repertoire. As a concerto player, Tasmin’s performances in the 2006/07 season took her on a major tour to South East Asia and Australia playing Elgar’s violin concerto celebrating the 150th anniversary of the composer’s birth as well as playing other repertoire in Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Singapore, Ireland and throughout England. She now play/directs orchestras such as Norwegian Chamber, London Mozart Players, Royal Philharmonic, European Union Chamber Orchestra and Britten Sinfonia. In 2007/08 she joins the London Mozart Players as a soloist and director in a tour of the UK which will also feature her UK conducting debut. -

Autumn Winter 2019/20

WHAT’S ON Autumn Winter 2019/20 WWW.THEMENUHINHALL.CO.UK SEASON AT A GLANCE WELCOME SEPTEMBER THURS 26 SEP 7.30pm SHOWCASE CONCERT 2 Juan March © Fundación We open a new Academic Year with all the excitement that new beginnings OCTOBER bring, and plenty of memorable musical performances ahead to delight SAT 5 OCT 7.30pm THE COBHAM BAND PRESENTS 2 you all. It has been wonderful to build upon the strong musical tradition of MUSIC FROM STAGE AND SCREEN the School and to extend our reach to audiences both local and beyond. FRI 11 OCT 7.30pm LAWRENCE POWER AND SIMON CRAWFORD-PHILLIPS 3 Lawrence Power and Simon Crawford-Phillips open our Celebrity TUES 15 OCT 7.30pm SHOWCASE CONCERT 4 series with a viola recital which promises to be charged with intensity SAT 19 OCT 7.30pm LONDON CONCERTANTE 4 and freshness. Bursting with youthful energy, the Piatti Quartet (with MON 28 OCT 10.30am THE ROMANTIC PERIOD WITH PETER MEDHURST 5 alumnus Tetsuumi Nagata on the viola) revisit the chamber music canon with their personal reading of works by Purcell, Haydn and Schubert. NOVEMBER In February, we will celebrate Beethoven’s 250th anniversary with a TUES 5 NOV 7.30pm PIATTI QUARTET 5 remarkable double bill, encompassing his complete works for cello and SAT 9 NOV 7.30pm WATERMILL JAZZ PRESENTS KEITH NICHOLS 6 piano performed by alumnus Colin Carr and Thomas Sauer. We are also AND THE BLUE DEVILS thrilled to welcome back alumna Tasmin Little as part of her farewell THURS 14 NOV 7.30pm SHOWCASE CONCERT 7 tour. -

Tasmin Little & Piers Lane

MELBOURNE RECITAL CENTRE PRESENTS 1 TASMIN LITTLE & PIERS LANE TUESDAY 23 OCTOBER 2018 GREAT PERFORMERS CONCERT SERIES 2018 ‘ Her playing communicated her certainty in what she was doing, which then allowed her intoxicating blend of power, passion, poetry and drop-dead beautiful playing to conjure a magic that just let the music flow.’ HERALD SCOTLAND PHOTO:BENJAMIN EALOVEGA VIOLIN & PIANO TASMIN LITTLE U.K. & PIERS LANE AUSTRALIA TUESDAY 23 OCTOBER 2018, 7.30PM Elisabeth Murdoch Hall 6.45PM Free pre-concert talk with Monica Curro DURATION One hour and 50-minutes including a 20-minute interval This concert is being recorded by ABC Classic FM for a deferred broadcast. Melbourne Recital Centre acknowledges the people of the Kulin Nation on whose land this concert is being presented. SERIES PARTNER LEGAL FRIENDS OF MELBOURNE RECITAL CENTRE PROGRAM TASMIN LITTLE & PIERS LANE JOHANNES BRAHMS INTERVAL 20-minutes (b. 1833, Hamburg, Germany – d. 1897, Vienna, Austria) ELENA KATS-CHERNIN (b. 1957, Tashkent, Uzbekistan) Scherzo from F-A-E Sonata Russian Rag Revisited – world premiere FRANZ SCHUBERT (b. 1797, Vienna, Austria – d. 1828, Vienna, MAURICE RAVEL (b. 1875, Ciboure, France – d. 1937, Paris, France) Austria) Pièce en forme de Habanera Sonatina in D, D.384 Allegro molto 4 CÉSAR FRANCK Andante (b. 1822, Liège, Belgium – d. 1890, Paris, France) Allegro vivace Sonata for violin & piano in A Allegretto ben moderato KAROL SZYMANOWSKI Allegro (b. 1882, Tymoshivka, Ukraine – d. 1937, Recitativo-Fantasia: Ben moderato Lausanne, Switzerland) Allegretto poco mosso Violin Sonata in D minor Allegro moderato Andantino tranquillo e dolce – Scherzando (più moto) - Tempo 1 Finale. -

Tasmin Little & Martin Roscoe

TASMIN LITTLE & MARTIN ROSCOE The Stoller Hall Tuesday 13 October 7.30pm IN PARTNERSHIP WITH MANCHESTER CHAMBER CONCERTS SOCIETY IN SUPPORT OF HELP MUSICIANS UK PROGRAMME Tasmin Little violin Martin Roscoe piano C SCHUMANN Three Romances, Op. 22 (10’) i Andante molto ii Allegretto: Mit zartem Vortrage iii Leidenschaftlich schnell BEETHOVEN Violin Sonata No. 5 in F major, Op. 24 ‘Spring’ (24’) i Allegro ii Adagio molto espressivo iii Scherzo: Allegro molto iv Rondo: Allegro ma non troppo Interval (15’) BEACH Romance, Op. 23 (6’) FRANCK Sonata in A major (28’) i Allegretto ben moderato ii Allegro iii Recitativo - Fantasia: Ben moderato iv Allegretto poco mosso C SCHUMANN Three Romances, Op. 22 Clara Schumann is known today mainly as the wife of composer Robert Schumann and the intimate friend of Johannes Brahms. In her 61-year concert career, however, she was considered one of the most distinguished pianists of her day, and was highly influential in programming new works by contemporary Romantic composers. She was also a prolific composer in her early years, at a time when women composers were frowned on by the music world. As she grew older, she lost confidence in herself as a composer, writing “I once believed that I possessed creative talent, but I have given up this idea; a woman must not desire to compose – there has never yet been one able to do it.” Clara began to compose again in the summer of 1853, having written little since 1846 and the period of her Piano Trio. The Three Romances were among the last pieces that Clara ever wrote, the Romance being one of Clara’s favourite character genres. -

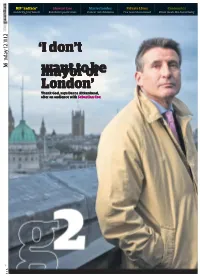

T Want to Be Mayor of London

RIP *sadface* Stewart Lee Mastectomies Private Lives Enonomics Celebrity grief tweets Rekebah’s poetic texts Cancer risk dilemma I’ve never been kissed Brian meets Ha-Joon Chang 1 2 1 . 1 . 1 2 y a ‘I don’t d n M o mayor want to of be London’ Thank God, says Decca Aitkenhead, after an audience with Sebastian Coe A 2 1 Shortcuts l i v e D u n n R I P C e s f o r a l l t h Eulogies t h a n k Gervais and Radio 1 DJ Greg James, n j o y m e n t o u r s o f e neither of whom I believe to have h D a d ’ s Reaping the w a t c h i n g been particular acquaintances of A r m y Nutkins, or, indeed, luminaries in Celebrity Death the wildlife-broadcasting world. Twitter Harvest Unless we count Flanimals. This year we have encountered the high-profile passings of Neil So sad to hear Armstrong, Tony Scott and Hal t is often suggested that the David, and naturally the coverage death of Diana, Princess of about Terry Nutkins. that followed them often drew on I Wales, altered the nature What an absolute celebrity tweets (“Everyone should of collective grief, rendering it icon go outside and look at the moon suddenly acceptable to line the tonight and give a thought to Neil streets, send flowers and, most Armstrong,” ordered McFly’s Tom importantly, weep publicly at the Fletcher). But few could match the death of someone you did not response that greeted the death of actually know. -

The Delius Society Journal

The Delius Society Journal Winter 1997, Number 122 The Delius Society (Registered Charity No. 298662) Full Membership and Institutions £15 per year USA and Canada US$31 per year Africa, Australasia and Far East £18 per year President Felix Aprahamian, I Ion D Mus, I Ion FRCO Vice Presidents Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (Founder Member) Meredith Davies CBE, MA, B Mus, FRCM, I Ion RAM Vernon I Iandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Richard I lickox FRCO (Cl IM) Rodney Meadows Robert Threlfall Clrairma11 Lyndon Jenkins Treas11rcr (to whom changes of address and membership queries should be directed) Derek Cox Mercers, 6 Mount Pleasant, Blockley, Clos GL56 9BU Tel: (01386) 700175 Secretary Anthony Lindsey 1 The Pound, Aldwick Village, West Sussex P021 3SR Tel: (01243) 824964 Editor Roger Buckley Magpie Shaw, Speldhurst, Kent TN3 OLE Tel: (01892) 863123 Fax: (0171) 935 5429 email: RJBucl<lcy <!_,Jaol.com Ch<1irman's Message........................................................................................... 5 Editorial................................................................................................................. 6 Delius Trust Press Release, 24 October 1997................................................... 7 ARTICLES Similar Cities? Delius's Paris, RVW's 1.m11io11 Sy111JJ!rcmy and Stravinsky's Petrouslika, by Robert Matthew-Walker............................. 8 The Loss at the I Ieart of his Music, by Tasmin Little (Daily Telegraph)...... 20 TI lE DELIUS TRUST (Part 1) An Account of the Delius Trust, by Martin Williams................................... -

17 April 2016 in Summary the Menuhin Competition London 2016 in Numbers

7 – 17 April 2016 In Summary The Menuhin Competition London 2016 in numbers • 307 entries from 40 countries • 17 nationalities represented by the 44 competitors and 9 jurors • Audience attendance at 28 ticketed live concerts and events of 12,000 • The estimated audience in attendance of the 14 free events during the Menuhin Competition Gala Weekend plus the 14 outreach activities across schools, UCL Hospital and an office visit is a further 4,000 • The live streaming of the competition rounds reached 33,894 people in over 138 countries worldwide (during the hours that the events were taking place) • Between 7th April and 6th May 2016 the Menuhin Competition YouTube channel was watched by 317,904 people from 162 countries • During the month of April 2016 the Menuhin Competition website had 423,310 page views (83,748 sessions) from 152 countries, 44.4% of whom were new visitors Worldwide reach Live streaming percentages of 33,894 YouTube channel percentages of viewers in over 138 countries 317,904 viewers in over 162 countries © Camilla Greenwell © Camilla Highlights Thank you to all of our partners, sponsors, supporters, host families and everybody that contributed to making the Menuhin Competition London 2016 the success that it was - a true celebration of the Menuhin centenary! Highlights and milestones achieved during the Menuhin Competition London 2016: • The Opening and Closing Gala concerts with the Philharmonia Orchestra at Southbank Centre’s Royal Festival Hall • Artistic excellence of both Junior and Senior competitors’ performances