The Importance of Keeping New Zealand Free of Tramp Ants Introduction Potential Human Health Risk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Indonesian Grasslands with Special Focus on the Tropical Fire Ant, Solenopsis Geminata

The Community Ecology of Ants (Formicidae) in Indonesian Grasslands with Special Focus on the Tropical Fire Ant, Solenopsis geminata. By Rebecca L. Sandidge A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, Policy, and Management in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Neil D. Tsutsui, Chair Professor Brian Fisher Professor Rosemary Gillespie Professor Ellen Simms Fall 2018 The Community Ecology of Ants (Formicidae) in Indonesian Grasslands with Special Focus on the Tropical Fire Ant, Solenopsis geminata. © 2018 By Rebecca L. Sandidge 1 Abstract The Community Ecology of Ants (Formicidae) in Indonesian Grasslands with Special Focus on the Tropical Fire Ant, Solenopsis geminata. by Rebecca L. Sandidge Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science Policy and Management, Berkeley Professor Neil Tsutsui, Chair Invasive species and habitat destruction are considered to be the leading causes of biodiversity decline, signaling declining ecosystem health on a global scale. Ants (Formicidae) include some on the most widespread and impactful invasive species capable of establishing in high numbers in new habitats. The tropical grasslands of Indonesia are home to several invasive species of ants. Invasive ants are transported in shipped goods, causing many species to be of global concern. My dissertation explores ant communities in the grasslands of southeastern Indonesia. Communities are described for the first time with a special focus on the Tropical Fire Ant, Solenopsis geminata, which consumes grass seeds and can have negative ecological impacts in invaded areas. The first chapter describes grassland ant communities in both disturbed and undisturbed grasslands. -

(Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the Arabian Peninsula, with the Description of Two New Species

European Journal of Taxonomy 246: 1–36 ISSN 2118-9773 http://dx.doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2016.246 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2016 · Sharaf M.R. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Research article urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:966C5DFD-72A9-4567-9DB7-E4C56974DDFA Taxonomy and distribution of the genus Trichomyrmex Mayr, 1865 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in the Arabian Peninsula, with the description of two new species Mostafa R. SHARAF 1,*, Shehzad SALMAN 2, Hathal M. AL DHAFER 3, Shahid A. AKBAR 4, Mahmoud S. ABDEL-DAYEM 5 & Abdulrahman S. ALDAWOOD 6 1,2,3,5,6 Plant Protection Department, College of Food and Agriculture Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, P. O. Box 2460, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 4 Central Institute of Temperate Horticulture, Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir, India. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 E-mail: [email protected] 3 E-mail: [email protected] 4 E-mail: [email protected] 5 E-mail: [email protected] 6 E-mail: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:E2A42091-0680-4A5F-A28A-2AA4D2111BF3 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:394BE767-8957-4B61-B79F-0A2F54DF608B 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:6117A7D3-26AF-478F-BFE7-1C4E1D3F3C68 4 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:5A0AC4C2-B427-43AD-840E-7BB4F2565A8B 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:AAAD30C4-3F8F-4257-80A3-95F78ED5FE4D 6 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:477070A0-365F-4374-A48D-1C62F6BC15D1 Abstract. The ant genus Trichomyrmex Mayr, 1865 is revised for the Arabian Peninsula based on the worker caste. Nine species are recognized and descriptions of two new species, T. -

Redescription of Monomorium Pallidumdonisthorpe, 1918, Revised

ASIAN MYRMECOLOGY — Volume 11, e011001, 2019 ISSN 1985-1944 | eISSN: 2462-2362 DOI: 10.20362/am.011001 Redescription of Monomorium pallidum Donisthorpe, 1918, revised status Lech Borowiec1*, Mohammad Saeed Mossadegh2, Sebastian Salata3, Shima Mohammadi4, Ebrahim Tamoli Torfi2, Mehdi Toosi2 and Ali Almasi2 1Department of Biodiversity and Evolutionary Taxonomy, University of Wrocław, Przybyszewskiego 65, 51-148 Wrocław, Poland 2Department of Plant Protection, College of Agriculture, Shahid Chamran University, Ahwaz, Iran 3Institute for Agricultural and Forest Environment, Polish Academy of Sciences, Bukowska 19, 60- 809 Poznań, Poland 4No.34, 62nd Alley Pasdaran Blvd., Shiraz, Iran *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Monomorium pallidum Donisthorpe, 1918 is redescribed based on material from Iran (new country record). It is removed from the genus Trichomyrmex Mayr, 1865, its species status is retrieved and placed in the M. monomorium group of the genus Monomorium Mayr, 1855. Keywords Iran, key, Monomorium monomorium-group, Palearctic Region, Middle East. Citation Lech Borowiec et al. (2019) Redescription of Monomorium pallidum Donisthorpe, 1918, revised status. Asian Myrmecology 11: e011001 Copyright This article is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution License CCBY4.0 Communicating Francisco Hita Garcia Editor INTRODUCTION iterraneo-Sindian region (Vigna Taglianti et al. 1999), with a large number of described infraspe- With 358 described species and 25 valid sub- cific taxa, stands in need of further investigation species, Monomorium Mayr, 1855 is one of the (Borowiec 2014). Thanks to the most recent revi- largest myrmicine genera, which is distributed sion of the Arabian species of the M. monomo- worldwide in tropical and warm temperate re- rium group (Sharaf et al. -

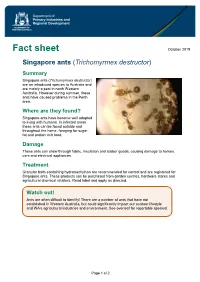

Fact Sheet October 2019

Fact sheet October 2019 Singapore ants (Trichomyrmex destructor) Summary Singapore ants (Trichomyrmex destructor) are an introduced species to Australia and are mainly a pest in north Western Australia. However during summer, these ants have caused problems in the Perth area. Where are they found? Singapore ants have become well adapted to living with humans. In infested areas these ants can be found outside and throughout the home, foraging for sugar, fat and protein rich food. Damage These ants can chew through fabric, insulation and rubber goods, causing damage to homes, cars and electrical appliances Treatment Granular baits containing hydramethylnon are recommended for control and are registered for Singapore ants. These products can be purchased from garden centres, hardware stores and agricultural chemical retailers. Read label and apply as directed. Watch out! Ants are often difficult to identify! There are a number of ants that have not established in Western Australia, but could significantly impact our outdoor lifestyle and WA’s agricultural industries and environment. See overleaf for reportable species! Page 1 of 2 Exotic ant threats to WA Under the Biosecurity and Agriculture Management Act 2007 (BAM Act) the introduction of these ants into WA is prohibited and any suspect sightings must be reported. Below are a few species we are particularly concerned about. Browsing ant (Lepisiota frauenfeldi) Native to southern Europe, they thrive in a Mediterranean climate and are ideally suited to Australian conditions. These aggressive ants form multi-queened super-colonies, quickly reaching very high populations and displacing native ant species and other invertebrates. They are also a significant horticultural and domestic pest. -

Hymenoptera: Formicidae)

ASIAN MYRMECOLOGY Volume 8, 17 – 48, 2016 ISSN 1985-1944 © Weeyawat Jaitrong, Benoit Guénard, Evan P. Economo, DOI: 10.20362/am.008019 Nopparat Buddhakala and Seiki Yamane A checklist of known ant species of Laos (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Weeyawat Jaitrong1, Benoit Guénard2, Evan P. Economo3, Nopparat Buddhakala4 and Seiki Yamane5* 1 Thailand Natural History Museum, National Science Museum, Technopolis, Khlong 5, Khlong Luang, Pathum Thani, 12120 Thailand E-mail: [email protected] 2 School of Biological Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, Pok Fu Lam Road, Hong Kong SAR, China 3 Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University, 1919-1 Tancha, Onna, Okinawa 904-0495, Japan 4 Biology Divisions, Faculty of Science and Technology, Rajamangala Univer- sity of Technology Tanyaburi, Pathum Thani 12120 Thailand E-mail: [email protected] 5 Kagoshima University Museum, Korimoto 1-21-30, Kagoshima-shi, 890-0065 Japan *Corresponding author’s email: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Laos is one of the most undersampled areas for ant biodiversity. We begin to address this knowledge gap by presenting the first checklist of Laotian ants. The list is based on a literature review and on specimens col- lected from several localities in Laos. In total, 123 species with three additional subspecies in 47 genera belonging to nine subfamilies are listed, including 62 species recorded for the first time in the country. Comparisons with neighboring countries suggest that this list is still very incomplete. The provincial distribu- tion of ants within Laos also show that most species recorded are from Vien- tiane Province, the central part of Laos while the majority of other provinces have received very little, if any, ant sampling. -

Review of the Ants of Scabriceps Group of the Genus Monomorium Mayr (Hymenoptera, Formicidae)

ANNALES Annales Zoologici (1997) 46: 211-224 ZOOLOGICI Review of the Ants of Scabriceps Group of the Genus Monomorium Mayr (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) Alexander G. RADCHENKO 1.1. Schmalhausen Institute of Zoology, Ukrainian National Academy of Sciences, Kiev, Ukraine A bstract. Monomorium perplexum sp. n. from Transcaucasus and Islands of Aegean Sea is described. M. dentigerum (Roger) and M. evansi Donisthorpe are redescribed; females and males of M. criniceps Mayr. are described first. M. perplexum differs from species of scabriceps group (except M. muticum Emery from Burma) by the absence of the long acute denticles on the anterior clypeal mar gin; it differs from M. muticum by smooth dorsum and sides of promesonotum. M. dentigerim and M. evansi are excluded from scabri ceps group and are united to the dentigerim group. Key of species of the two groups is compiled. Key words: Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Monomorium, taxonomy. INTRODUCTION 1921, and genus Trichomyrmex Mayr, 1865, described from only one female from Ceylon. Genus Holcomyrmex was first described by Mayr M. scabriceps group includes 8 species. Six of (1879). Later Emery considered it as species group them are distributed in South and South-East Asia (Emery, 1908) and as subgenus of the genus (India, Burma, Sri Lanka), one - in Afrotropical Monomorium (Emery, 1921). Ettershank (1966) syn- region throughout Sahelian zone (Bolton, 1987). One onymised Holcomyrmex with Monomorium , and species described below as new from Transcaucasus, reduced all subgenera in this genus. Bolton (1987) Turkey and isles of Aegean. proposed a new system of Monomorium and defined All these species are distinctive polymorphic and in it 8 species groups for Afrotropical region. -

The World's First Inquiline Flatid

TABLE OF CONTENTS KEYNOTE SPEAKERS Deep transcriptome insights into cave beetle eyes 1 Marcus Friedrich Aedes control: the future is now! 2 Hoffmann, A.A. The Hemipteroid Tree of Life 3 Kevin P. Johnson Biosecurity in northern Australia 4 James A. Walker Seeing at the limits: vision and visual navigation in nocturnal insects 5 Eric Warrant ORAL PRESENTATIONS Dung beetle (Coleoptera, Scarabaeidae) abundance and diversity at nature preserve within hyper-arid ecosystem of Arabian Peninsula 6 Abdel-Dayem, M., Kondratieff, B., Fadl , H.(1) and Aldhafer, H. Screening of sugarcane cultivars to assess the incidence against Chilo infuscatellus (Pyralidae, Lepidoptera) 6 Ahmad, S., Qurban, A. and Zahid, A. Microbiology and nutritional composition of some edible insects 7 Amadi, E.N. Studies on the mopane worm, Imbrasia belina an edible caterpillar 7 Allotey, J. DNA barcoding identification of mosquitoes using traditional and next-generation sequencing techniques 8 Batovska, J., Lynch, S., Cogan, N., Brown, K. and Blacket, M.J. Towards a compelling phylogeny of cyclorrhaphan flies (Diptera) using whole body adult transcriptomes 9 Bayless, K.M., Trautwein, M.D., Meusemann, K., Yeates, D.K. and Wiegmann, B.M. Establishing a population genetics toolbox and regional spatial database to facilitate identfying the incursion origin of the dengue mosquito Aedes aeqypti and the Asian tiger Ae. albopictus 10 Beebe, N.W. A summary of interceptions and additions to the New Zealand fauna, with reference to Australian origins 11 Bennett, S.J. The role of nutrition in determining individual and group patterns of behaviour 12 Berville, L., Hoffmann, B. and Suarez, A. Australian millipede diversity: an update 13 Black, D. -

(Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Oman: an Updated List, New Records and a Description of Two New Species

ASIAN MYRMECOLOGY Volume 10, e010004, 2018 ISSN 1985-1944 | eISSN: 2462-2362 © Mostafa R. Sharaf, Brian L. Fisher, DOI: 10.20362/am.010004 Hathal M. Al Dhafer, Andrew Polaszek and Abdulrahman S. Aldawood Additions to the ant fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Oman: an updated list, new records and a description of two new species Mostafa R. Sharaf1*, Brian L. Fisher2, Hathal M. Al Dhafer1, Andrew Polaszek3 and Abdulrahman S. Aldawood1 1Plant Protection Department, College of Food and Agriculture Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh 11451, P. O. Box 2460, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 2Department of Entomology, California Academy of Sciences, Golden Gate Park, 55 Music Concourse Drive, San Francisco, California 94118, USA. 3Department of Life Sciences, Natural History Museum, London SW7 5BD U.K. *Corresponding author: [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT. An updated list of ant species (Formicidae) known from Oman is provided, including both published records and recently collected material, and bringing the total number to 123 species belonging to 24 genera and four subfamilies. In the present study thirty-four ant species were collected from Oman during expeditions in 2016 and 2017. Ten ant species are recorded for the first time in Oman :Cardiocondyla breviscapa Seifert, 2003, C. mauritanica Forel, 1890, C. yemeni Collingwood & Agosti, 1996, Erromyrma latinodis (Mayr, 1872), Hypoponera abeillei (André, 1881), Lepisiota opaciventris (Finzi, 1936), Monomorium dichroum Forel, 1902, Pheidole parva Mayr, 1865, Plagiolepis boltoni Sharaf, Aldawood & Taylor, 2011, and Tetramorium lanuginosum Mayr, 1870. The genus Aphaenogaster is recorded for the first time from Oman, and two new species of Aphaenogaster are described based on the worker caste: A. -

1803456116.Full.Pdf

Correction ECOLOGY Correction for “Predicting future invaders and future invasions,” by Alice Fournier, Caterina Penone, Maria Grazia Pennino, and Franck Courchamp, which was first published March 29, 2019; 10.1073/pnas.1803456116 (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 7905–7910). The authors note that due to a technical error in the script that selected the species based on their amount of missing values, the species names did not match their trait values. This resulted in the wrong set of species to be evaluated for their invasive po- tential. This error affects the invasiveness probabilities and in- vasive identity in Table 1 and Fig. 1, and associated numbers in text; the cumulative map in Fig. 2C; and, in the SI Appendix, Figs. S1, S5, S8A, S9, and S11 and Tables S1, S3, S4, and S5. CORRECTION PNAS 2021 Vol. 118 No. 31 e2110631118 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2110631118 | 1of3 Downloaded by guest on September 29, 2021 Table 1. Predicted invasiveness probabilities, or “invasion profiles,” of 19 invasive species from the IUCN red list (in boldface) and 18 potential future invaders identified with our model Species P ± % Superinvasive profiles Technomyrmex difficilis 0.87 0.02 100 Lasius neglectus 0.87 0.02 100 Solenopsis geminata 0.87 0.02 100 Solenopsis invicta 0.87 0.02 100 Technomyrmex albipes 0.87 0.02 100 Trichomyrmex destructor 0.87 0.02 100 Lepisiota canescens 0.83 0.01 100 Anoplolepis gracilipes 0.83 0.01 100 Linepithema humile 0.83 0.01 100 Monomorium pharaonis 0.83 0.01 100 Myrmica rubra 0.83 0.01 100 Nylanderia pubens 0.83 -

Of Sri Lanka: a Taxonomic Research Summary and Updated Checklist

ZooKeys 967: 1–142 (2020) A peer-reviewed open-access journal doi: 10.3897/zookeys.967.54432 CHECKLIST https://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research The Ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of Sri Lanka: a taxonomic research summary and updated checklist Ratnayake Kaluarachchige Sriyani Dias1, Benoit Guénard2, Shahid Ali Akbar3, Evan P. Economo4, Warnakulasuriyage Sudesh Udayakantha1, Aijaz Ahmad Wachkoo5 1 Department of Zoology and Environmental Management, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka 2 School of Biological Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China3 Central Institute of Temperate Horticulture, Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir, 191132, India 4 Biodiversity and Biocomplexity Unit, Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University, Onna, Okinawa, Japan 5 Department of Zoology, Government Degree College, Shopian, Jammu and Kashmir, 190006, India Corresponding author: Aijaz Ahmad Wachkoo ([email protected]) Academic editor: Marek Borowiec | Received 18 May 2020 | Accepted 16 July 2020 | Published 14 September 2020 http://zoobank.org/61FBCC3D-10F3-496E-B26E-2483F5A508CD Citation: Dias RKS, Guénard B, Akbar SA, Economo EP, Udayakantha WS, Wachkoo AA (2020) The Ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of Sri Lanka: a taxonomic research summary and updated checklist. ZooKeys 967: 1–142. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.967.54432 Abstract An updated checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Sri Lanka is presented. These include representatives of eleven of the 17 known extant subfamilies with 341 valid ant species in 79 genera. Lio- ponera longitarsus Mayr, 1879 is reported as a new species country record for Sri Lanka. Notes about type localities, depositories, and relevant references to each species record are given. -

Resource Productivity in the Irrigated

ISSN 0258-7122 (Print), 2408-8293 (Online) Bangladesh J. Agril. Res. 44(4): 679-688, December 2019 SPECIES DIVERSITY AND RICHNESS OF ANT (Hymenoptera, formicidae) IN BHAWAL NATIONAL PARK OF BANGLADESH M. M. RAHMAN1 AND M. N. JAHAN2 Abstract Ant community serves as an bioindicator on the assumption that the extent of ant diversity reflects broader ecosystem change. Bangladesh with varied agro ecosystem providing broad ecological niche of diversified ant community. The study of ant community is a way to measure the recent transformation of agro ecosystems in Bangladesh to provide information about management and conservation of agricultural landscape. The present study was conducted in Bhawal National Park to delve deeper into the diversity and richness of ants as they work as ecological indicators of an ecosystem. Being a conservation site with natural resources, Bhawal National Park can serve as study site with species diversity due to having sites with similar vegetation and soil type, but different ecological parameters. The objective of the study was to identify local ant fauna in forest agroecosystem to understand the impact on human disturbance to ant communities of the study area. Total 399 individuals were identified from 42 species of 17 genera belonging to 6 subfamilies. Sampling was performed using Time unit sampling (TUS) and pitfall trap in two different areas, viz, area 1 and 2. The most dominant subfamily of the study area was Myrmicinae. The highest number of species were found from the genus Camponotus. The Shannon-Wiener's Diversity Index showed that area 1 had higher species diversity due to favorable living conditions with less animal intervention and higher density of vegetation playing key role. -

Phylogeny and Biogeography of a Hyperdiverse Ant Clade (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title The evolution of myrmicine ants: Phylogeny and biogeography of a hyperdiverse ant clade (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2tc8r8w8 Journal Systematic Entomology, 40(1) ISSN 0307-6970 Authors Ward, PS Brady, SG Fisher, BL et al. Publication Date 2015 DOI 10.1111/syen.12090 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Systematic Entomology (2015), 40, 61–81 DOI: 10.1111/syen.12090 The evolution of myrmicine ants: phylogeny and biogeography of a hyperdiverse ant clade (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) PHILIP S. WARD1, SEÁN G. BRADY2, BRIAN L. FISHER3 andTED R. SCHULTZ2 1Department of Entomology and Nematology, University of California, Davis, CA, U.S.A., 2Department of Entomology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, U.S.A. and 3Department of Entomology, California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, CA, U.S.A. Abstract. This study investigates the evolutionary history of a hyperdiverse clade, the ant subfamily Myrmicinae (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), based on analyses of a data matrix comprising 251 species and 11 nuclear gene fragments. Under both maximum likelihood and Bayesian methods of inference, we recover a robust phylogeny that reveals six major clades of Myrmicinae, here treated as newly defined tribes and occur- ring as a pectinate series: Myrmicini, Pogonomyrmecini trib.n., Stenammini, Solenop- sidini, Attini and Crematogastrini. Because we condense the former 25 myrmicine tribes into a new six-tribe scheme, membership in some tribes is now notably different, espe- cially regarding Attini. We demonstrate that the monotypic genus Ankylomyrma is nei- ther in the Myrmicinae nor even a member of the more inclusive formicoid clade – rather it is a poneroid ant, sister to the genus Tatuidris (Agroecomyrmecinae).