Rhodonite (Mn2+,Fe2+,Mg, Ca)Sio3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Mineralogical Study of the La Hueca Cretaceous Iron-Manganese

Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas ISSN: 1026-8774 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México México Corona Esquivel, Rodolfo; Ortega Gutiérrez, Fernando; Reyes Salas, Margarita; Lozano Santacruz, Rufino; Miranda Gasca, Miguel Angel Mineralogical study of the La Hueca Cretaceous Iron-Manganese deposit, Michoacán, south-western Mexico Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, vol. 17, núm. 2, 2000, pp. 142-151 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Querétaro, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=57217206 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, volumen 17, número 2, 143 2000, p. 143- 153 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Geología, México, D.F MINERALOGICAL STUDY OF THE LA HUECA CRETACEOUS IRON- MANGANESE DEPOSIT, MICHOACÁN, SOUTHWESTERN MEXICO Rodolfo Corona-Esquivel1, Fernando Ortega-Gutiérrez1, Margarita Reyes-Salas1, Rufino Lozano-Santacruz1, and Miguel Angel Miranda-Gasca2 ABSTRACT In this work we describe for the first time the mineralogy and very briefly the possible origin of a banded Fe-Mn deposit associated with a Cretaceous volcanosedimentary sequence of the southern Guerrero terrane, near the sulfide massive volcanogenic deposit of La Minita. The deposit is confined within a felsic tuff unit; about 10 meters thick where sampled for chemical analysis. Using XRF, EDS and XRD techniques, we found besides todorokite, cryptomelane, quartz, romanechite (psilomelane), birnessite, illite-muscovite, cristobalite, chlorite, barite, halloysite, woodruffite, nacrite or kaolinite, and possibly hollandite-ferrian, as well as an amorphous material and two unknown manganese phases. -

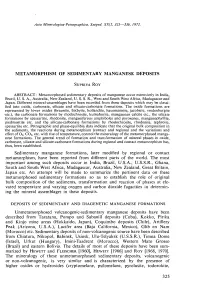

Metamorphism of Sedimentary Manganese Deposits

Acta Mineralogica-Petrographica, Szeged, XX/2, 325—336, 1972. METAMORPHISM OF SEDIMENTARY MANGANESE DEPOSITS SUPRIYA ROY ABSTRACT: Metamorphosed sedimentary deposits of manganese occur extensively in India, Brazil, U. S. A., Australia, New Zealand, U. S. S. R., West and South West Africa, Madagascar and Japan. Different mineral-assemblages have been recorded from these deposits which may be classi- fied into oxide, carbonate, silicate and silicate-carbonate formations. The oxide formations are represented by lower oxides (braunite, bixbyite, hollandite, hausmannite, jacobsite, vredenburgite •etc.), the carbonate formations by rhodochrosite, kutnahorite, manganoan calcite etc., the silicate formations by spessartite, rhodonite, manganiferous amphiboles and pyroxenes, manganophyllite, piedmontite etc. and the silicate-carbonate formations by rhodochrosite, rhodonite, tephroite, spessartite etc. Pétrographie and phase-equilibia data indicate that the original bulk composition in the sediments, the reactions during metamorphism (contact and regional and the variations and effect of 02, C02, etc. with rise of temperature, control the mineralogy of the metamorphosed manga- nese formations. The general trend of formation and transformation of mineral phases in oxide, carbonate, silicate and silicate-carbonate formations during regional and contact metamorphism has, thus, been established. Sedimentary manganese formations, later modified by regional or contact metamorphism, have been reported from different parts of the world. The most important among such deposits occur in India, Brazil, U.S.A., U.S.S.R., Ghana, South and South West Africa, Madagascar, Australia, New Zealand, Great Britain, Japan etc. An attempt will be made to summarize the pertinent data on these metamorphosed sedimentary formations so as to establish the role of original bulk composition of the sediments, transformation and reaction of phases at ele- vated temperature and varying oxygen and carbon dioxide fugacities in determin- ing the mineral assemblages in these deposits. -

Jacobsite from the Tamworth District of New South Wales

538 Jacobsite from the Tamworth district of New South Wales. By F .L. STILLWELL, D.Sc., and A. B. EDWAP~DS,D.Sc., Ph.D., D.I.C. Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Organization, Melbourne. [Taken as read November 2, 1950.] WO new occurrences of the rare manganese mineral jacobsite T (MnF%0~) have come to light in the course of mineragraphic studies carried out as part of the research programme of the Mineragraphic Section of the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization. The jacobsite occurs as a constituent of small bodies of high-grade manganese ore at Weabonga, near Danglemah, and at the Mount Sally mine, about 6 miles west of Danglemah, both in the Tam- worth district of New South Wales. The deposits occur in altered sediments, within a mile or two of a granite contact. 1 They are irregular lenticular veins ranging from a few inches to several feet in thickness, between altered slate walls. The veins do not exceed a length of 200-300 feet. The lode material consists of manganese oxides, chiefly psilomelane and pyrolusite, associated with quartz, rhodonite, and iron oxide. The manganese oxides are mainly supergene, and although the deposits are of high grade near the surface, it is doubtful whether they can be worked below the depths of 50- 60 feet, owing to the increase in the amount of rhodonite and quartz relative to manganese oxides at this depth. In the Weabonga ore the jacobsite occurs as narrow seams and lenticles, about 0.5 cm. across, and 3.0 cm. long enclosed in, and partly replaced by, pyrolusite and psilomelane. -

The Wittelsbach-Graff and Hope Diamonds: Not Cut from the Same Rough

THE WITTELSBACH-GRAFF AND HOPE DIAMONDS: NOT CUT FROM THE SAME ROUGH Eloïse Gaillou, Wuyi Wang, Jeffrey E. Post, John M. King, James E. Butler, Alan T. Collins, and Thomas M. Moses Two historic blue diamonds, the Hope and the Wittelsbach-Graff, appeared together for the first time at the Smithsonian Institution in 2010. Both diamonds were apparently purchased in India in the 17th century and later belonged to European royalty. In addition to the parallels in their histo- ries, their comparable color and bright, long-lasting orange-red phosphorescence have led to speculation that these two diamonds might have come from the same piece of rough. Although the diamonds are similar spectroscopically, their dislocation patterns observed with the DiamondView differ in scale and texture, and they do not show the same internal strain features. The results indicate that the two diamonds did not originate from the same crystal, though they likely experienced similar geologic histories. he earliest records of the famous Hope and Adornment (Toison d’Or de la Parure de Couleur) in Wittelsbach-Graff diamonds (figure 1) show 1749, but was stolen in 1792 during the French T them in the possession of prominent Revolution. Twenty years later, a 45.52 ct blue dia- European royal families in the mid-17th century. mond appeared for sale in London and eventually They were undoubtedly mined in India, the world’s became part of the collection of Henry Philip Hope. only commercial source of diamonds at that time. Recent computer modeling studies have established The original ancestor of the Hope diamond was that the Hope diamond was cut from the French an approximately 115 ct stone (the Tavernier Blue) Blue, presumably to disguise its identity after the that Jean-Baptiste Tavernier sold to Louis XIV of theft (Attaway, 2005; Farges et al., 2009; Sucher et France in 1668. -

STREAK Streak Means the Color of a Mineral in Its Powdered Form. The

STREAK Streak means the color of a mineral in its powdered form. The name comes from the common method of observing it by scraping the mineral on a tile of white, unglazed porcelain to produce a narrow streak of powder. Streak is a valuable property because its color is usually the same even when larger samples of many minerals show a variety of colors. Streak is often better for mineral identification than color. Streak of metallic minerals Streak is valuable for identification of many metallic minerals, including native metals (such as gold), oxides and sulfide. Almost all of these minerals have metallic or submetallic luster and are opaque. Their streak is often quite different from their color in a hand sample, generally darker. Examples: Hematite: Hematite can occur as black crystals, steel gray in the form known as specularite, and as dull red earthy masses. Its streak, however, is always blood red. By this simple test hematite can be known apart from other black, metallic minerals of similar appearance. Pyrite: Pyrite comes in a brassy yellow color, but has a black or greenish-black streak. It is sometimes called “fool’s gold” because people mistook specks in ores for real gold. But native gold has a gold streak. Chalcopyrite and marcasite are closely related to pyrite. They have paler brassy colors than pyrite, but also show dark streaks. Bornite: Bornite is bronze color when fresh, but quickly tarnishes to blue and purple shades, and eventually turns black. Its streak, however, is always grayish black. Streak of nonmetallic minerals In contrast, most minerals with nonmetallic lusters are transparent or translucent, and have a streak paler than their color in hand-samples. -

Speciation of Manganese in a Synthetic Recycling Slag Relevant for Lithium Recycling from Lithium-Ion Batteries

metals Article Speciation of Manganese in a Synthetic Recycling Slag Relevant for Lithium Recycling from Lithium-Ion Batteries Alena Wittkowski 1, Thomas Schirmer 2, Hao Qiu 3 , Daniel Goldmann 3 and Ursula E. A. Fittschen 1,* 1 Institute of Inorganic and Analytical Chemistry, Clausthal University of Technology, Arnold-Sommerfeld Str. 4, 38678 Clausthal-Zellerfeld, Germany; [email protected] 2 Department of Mineralogy, Geochemistry, Salt Deposits, Institute of Disposal Research, Clausthal University of Technology, Adolph-Roemer-Str. 2A, 38678 Clausthal-Zellerfeld, Germany; [email protected] 3 Department of Mineral and Waste Processing, Institute of Mineral and Waste Processing, Waste Disposal and Geomechanics, Clausthal University of Technology, Walther-Nernst-Str. 9, 38678 Clausthal-Zellerfeld, Germany; [email protected] (H.Q.); [email protected] (D.G.) * Correspondence: ursula.fi[email protected]; Tel.: +49-5323-722205 Abstract: Lithium aluminum oxide has previously been identified to be a suitable compound to recover lithium (Li) from Li-ion battery recycling slags. Its formation is hampered in the presence of high concentrations of manganese (9 wt.% MnO2). In this study, mock-up slags of the system Li2O-CaO-SiO2-Al2O3-MgO-MnOx with up to 17 mol% MnO2-content were prepared. The man- ganese (Mn)-bearing phases were characterized with inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES), X-ray diffraction (XRD), electron probe microanalysis (EPMA), and X-ray absorption near edge structure analysis (XANES). The XRD results confirm the decrease of LiAlO2 phases from Mn-poor slags (7 mol% MnO2) to Mn-rich slags (17 mol% MnO2). -

Mineral Processing

Mineral Processing Foundations of theory and practice of minerallurgy 1st English edition JAN DRZYMALA, C. Eng., Ph.D., D.Sc. Member of the Polish Mineral Processing Society Wroclaw University of Technology 2007 Translation: J. Drzymala, A. Swatek Reviewer: A. Luszczkiewicz Published as supplied by the author ©Copyright by Jan Drzymala, Wroclaw 2007 Computer typesetting: Danuta Szyszka Cover design: Danuta Szyszka Cover photo: Sebastian Bożek Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wrocławskiej Wybrzeze Wyspianskiego 27 50-370 Wroclaw Any part of this publication can be used in any form by any means provided that the usage is acknowledged by the citation: Drzymala, J., Mineral Processing, Foundations of theory and practice of minerallurgy, Oficyna Wydawnicza PWr., 2007, www.ig.pwr.wroc.pl/minproc ISBN 978-83-7493-362-9 Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................9 Part I Introduction to mineral processing .....................................................................13 1. From the Big Bang to mineral processing................................................................14 1.1. The formation of matter ...................................................................................14 1.2. Elementary particles.........................................................................................16 1.3. Molecules .........................................................................................................18 1.4. Solids................................................................................................................19 -

Chromite Crystal Structure and Chemistry Applied As an Exploration Tool

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository February 2015 Chromite Crystal Structure and Chemistry applied as an Exploration Tool Patrick H.M. Shepherd The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Roberta L. Flemming The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Geology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Science © Patrick H.M. Shepherd 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Shepherd, Patrick H.M., "Chromite Crystal Structure and Chemistry applied as an Exploration Tool" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 2685. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/2685 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Western University Scholarship@Western University of Western Ontario - Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository Chromite Crystal Structure and Chemistry Applied as an Exploration Tool Patrick H.M. Shepherd Supervisor Roberta Flemming The University of Western Ontario Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Geology Commons This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Western Ontario - Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chromite Crystal Structure and Chemistry Applied as an Exploration Tool (Thesis format: Integrated Article) by Patrick H.M. -

Chapter 3 Nonsilicate Minerals the 8 Most Common Elements in the Continental Crust Elements That Comprise Most Minerals Classification of Minerals

Chapter 3 Nonsilicate Minerals The 8 Most Common Elements in the Continental Crust Elements That Comprise Most Minerals Classification of Minerals ! "Important nonsilicate minerals •" Several major groups exist including –"Oxides –"Sulfides –"Sulfates –"Native Elements –"Carbonates –"Halides –"Phosphates Classification of Minerals ! "Important nonsilicate minerals •" Many nonsilicate minerals have economic value •" Examples –"Hematite (oxide mined for iron ore) –"Halite (halide mined for salt) –"Sphalerite (sulfide mined for zinc ore) –"Native Copper (native element mined for copper) Table 3.2 (Modified) Common Nonsilicate Mineral Groups Classification of Minerals ! "Important nonsilicate minerals •" Oxides – natural compounds in which Oxygen anions combine w/ a variety of metal cations –"Ores of various metals –"Hematite & Magnetite (iron oxides), Chromite (iron-chromium oxide), Ilmenite (iron-titanium oxide) and Ice (H2O – the solid form of water) are some important oxides Hematite (Fe2O3) Ore of Iron Red Streak Metallic to Earthy Luster Black or Red Color Magnetite (Fe3O4) Ore of Iron Strong Magnetism Black Color Hardness (6) Metallic Luster Corundum (Ruby& Sapphire) (Al2O3) Gemstone Hardness = 9 (Scratches Knife), Hexagonal Crystals, Adamantine Luster, Color Variable, But Can Be Red (Ruby) or Blue (Sapphire) Chromite (FeCr2O4) Ore of Chromium Metallic to Submetallic Luster Iron Black to Brownish Black Color Octahedral Crystal Form Hardness (5.5-6) Ilmenite (FeTiO3) Ore of Titanium Black-Brownish Black Streak Metallic to Submetallic -

Mineral Identification

Mineral Identification Let’s identify some minerals! What do good scientists do? GOOD SCIENTISTS… ⚫ work together and share their information. ⚫ observe carefully. ⚫ record their observations. ⚫ learn from their observations and continue to test, examine, and discuss. What are minerals? MINERALS ARE… ⚫ matter. ⚫ inorganic (nonliving) solids found in nature. ⚫ made up of elements such as silicon, oxygen, carbon, iron. ( Si O C Fe) ⚫ NOT ROCKS!! Rocks are made up of minerals. Physical Properties ⚫ What are physical properties of matter? ⚫ Shape, color, texture, size, etc. ⚫ The physical properties of minerals are… ⚫Transparency ⚫Luster ⚫Fracture ⚫COLOR ⚫Cleavage ⚫STREAK ⚫Specific Gravity ⚫Crystal Form ⚫HARDNESS Physical Properties ⚫ Some physical properties of minerals we won’t be examining in this lab: How well light passes ⚫Transparency through ⚫ Fracture/Cleavage How it breaks ⚫ Crystal Form The pattern of its crystal formation Color Some minerals are easy to identify by color. ⚫ Malachite is always green. But the color of other minerals change when there are traces of other elements. ⚫ Quartz is clear in its purest form. ⚫ With traces of iron, it becomes purple…amethyst. ⚫ With traces of manganese, it become pink…rose quartz. Takeaway: Visual color helps in identification. Because visual color can be affected by traces of elements, scientists use another test, of streak color. Streak ⚫ Rubbing a mineral firmly across an unglazed porcelain tile (streak plate) leaves a line of powder. ⚫ The streak color of a mineral is always the same, regardless of its visual color. ⚫ For instance, both amethyst and rose quartz leave the white streak of quartz in its purest form. Takeaway: Streak color is an even more reliable way to identify a mineral. -

Global Building Blocks: Rocks and Mineral Identification

Cave of the Winds Activity Eleven: Global Building Blocks Lesson for Grades 9-12 One lab of about 50 minutes Global Building Blocks: Satisfies Colorado Rocks and Mineral Identification Model Content Standard for Science, Standard 4, Objectives Benchmark #1 for grades The learner will: 9-12: The earth’s interior has 1. Learn about mineral composition and identification. a composition and a structure. 2. Understand the rock cycle and identify some common rocks in each group. Prerequisite: knowledge of Vocabulary elements Mineral, rock, crystal structure, chemical composition, hardness, luster, cleavage, carbonates, rock cycle, igneous rock, metamorphic rock, sediment, clast, chemical sedimentary rock, bio- chemical sedimentary rock, siliciclastic sedimentary rock, sedimentary rock, parent rock, metamorphism, magma, crystallization, cementation, evaporite, metallic, nonmetallic, stria- tions, rhombus, transparent, translucent, physical weathering, chemical weathering, erosion, rock cycle, basalt, granite, trona, limestone, conglomerate, sandstone, shale, coquina, coal, gneiss, schist, marble, slate, mafic, felsic, foliated, crystalline, texture, vesicular, ooids, pebbles, sand, gravel, grain size, clay, organic material, ultraviolet light, hydrochloric acid, efferves- cence, streak, calcite, dolomite, gypsum, halite, sulfur, pyrite, muscovite mica, orthoclase feldspar, quartz. Background Information The Earth’s building blocks are rocks and minerals. Minerals, of which rocks are composed, are defined by standard criteria: 1) specific chemical -

Mineral Collecting Sites in North Carolina by W

.'.' .., Mineral Collecting Sites in North Carolina By W. F. Wilson and B. J. McKenzie RUTILE GUMMITE IN GARNET RUBY CORUNDUM GOLD TORBERNITE GARNET IN MICA ANATASE RUTILE AJTUNITE AND TORBERNITE THULITE AND PYRITE MONAZITE EMERALD CUPRITE SMOKY QUARTZ ZIRCON TORBERNITE ~/ UBRAR'l USE ONLV ,~O NOT REMOVE. fROM LIBRARY N. C. GEOLOGICAL SUHVEY Information Circular 24 Mineral Collecting Sites in North Carolina By W. F. Wilson and B. J. McKenzie Raleigh 1978 Second Printing 1980. Additional copies of this publication may be obtained from: North CarOlina Department of Natural Resources and Community Development Geological Survey Section P. O. Box 27687 ~ Raleigh. N. C. 27611 1823 --~- GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SECTION The Geological Survey Section shall, by law"...make such exami nation, survey, and mapping of the geology, mineralogy, and topo graphy of the state, including their industrial and economic utilization as it may consider necessary." In carrying out its duties under this law, the section promotes the wise conservation and use of mineral resources by industry, commerce, agriculture, and other governmental agencies for the general welfare of the citizens of North Carolina. The Section conducts a number of basic and applied research projects in environmental resource planning, mineral resource explora tion, mineral statistics, and systematic geologic mapping. Services constitute a major portion ofthe Sections's activities and include identi fying rock and mineral samples submitted by the citizens of the state and providing consulting services and specially prepared reports to other agencies that require geological information. The Geological Survey Section publishes results of research in a series of Bulletins, Economic Papers, Information Circulars, Educa tional Series, Geologic Maps, and Special Publications.