HKLJ3-4 Chen Jianlin-Ho Tung Gardens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Discussion on 15 July 2011

CB(1)2690/10-11(03) For discussion on 15 July 2011 Legislative Council Panel on Development Progress Report on Heritage Conservation Initiatives and Revitalisation of the Old Tai Po Police Station, the Blue House Cluster and the Stone Houses under the Revitalising Historic Buildings Through Partnership Scheme PURPOSE This paper updates Members on the progress made on the heritage conservation initiatives under Development Bureau’s purview since our last progress report in November 2010 (Legislative Council (LegCo) Paper No. CB(1)467/10-11(04)), and invites Members’ views on our future work. It also seeks Members’ support for the funding application for revitalising the Old Tai Po Police Station, the Blue House Cluster and the Stone Houses under the Revitalising Historic Buildings Through Partnership Scheme (Revitalisation Scheme). PROGRESS MADE ON HERITAGE CONSERVATION INITIATIVES Public Domain Revitalisation Scheme Batch I 2. For the six projects under Batch I of the Revitalisation Scheme, the latest position is as follows – (a) Former North Kowloon Magistracy – The site has been revitalised and adaptively re-used as the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) Hong Kong Campus for the provision of non-local higher education courses in the fields of art and design. Commencing operation in September 2010, SCAD Hong Kong is the first completed project under the Revitalisation Scheme. For the Fall 2010 term, 141 students were enrolled, of which about 40% are local students. In April 2011, SCAD Hong Kong obtained accreditation from the Hong Kong Council for Accreditation of Academic and Vocational Qualifications for five years for 14 programmes it offers at the Hong Kong campus. -

DEVB(W)-E2.Doc

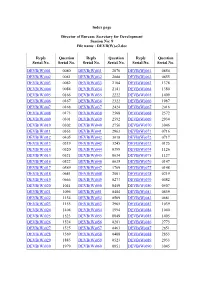

Index page Director of Bureau: Secretary for Development Session No: 9 File name : DEVB(W)-e2.doc Reply Question Reply Question Reply Question Serial No. Serial No. Serial No. Serial No. Serial No. Serial No. DEVB(W)001 0080 DEVB(W)031 2070 DEVB(W)061 0854 DEVB(W)002 0081 DEVB(W)032 2088 DEVB(W)062 0855 DEVB(W)003 0082 DEVB(W)033 2104 DEVB(W)063 1378 DEVB(W)004 0084 DEVB(W)034 2141 DEVB(W)064 1380 DEVB(W)005 0166 DEVB(W)035 2222 DEVB(W)065 1409 DEVB(W)006 0167 DEVB(W)036 2322 DEVB(W)066 1987 DEVB(W)007 0168 DEVB(W)037 2424 DEVB(W)067 2016 DEVB(W)008 0173 DEVB(W)038 2568 DEVB(W)068 2572 DEVB(W)009 0301 DEVB(W)039 2592 DEVB(W)069 2934 DEVB(W)010 0302 DEVB(W)040 2756 DEVB(W)070 3046 DEVB(W)011 0363 DEVB(W)041 2963 DEVB(W)071 0716 DEVB(W)012 0405 DEVB(W)042 3018 DEVB(W)072 0717 DEVB(W)013 0519 DEVB(W)043 3245 DEVB(W)073 0125 DEVB(W)014 0520 DEVB(W)044 0399 DEVB(W)074 1126 DEVB(W)015 0521 DEVB(W)045 0634 DEVB(W)075 1127 DEVB(W)016 0522 DEVB(W)046 0635 DEVB(W)076 0147 DEVB(W)017 0589 DEVB(W)047 1769 DEVB(W)077 0148 DEVB(W)018 0641 DEVB(W)048 2001 DEVB(W)078 0219 DEVB(W)019 0666 DEVB(W)049 0273 DEVB(W)079 0482 DEVB(W)020 1041 DEVB(W)050 0459 DEVB(W)080 0507 DEVB(W)021 1096 DEVB(W)051 0484 DEVB(W)081 0639 DEVB(W)022 1154 DEVB(W)052 0509 DEVB(W)082 0681 DEVB(W)023 1155 DEVB(W)053 2965 DEVB(W)083 1039 DEVB(W)024 1404 DEVB(W)054 1994 DEVB(W)084 1040 DEVB(W)025 1523 DEVB(W)055 0049 DEVB(W)085 1405 DEVB(W)026 1524 DEVB(W)056 0281 DEVB(W)086 2773 DEVB(W)027 1525 DEVB(W)057 0463 DEVB(W)087 2851 DEVB(W)028 1569 DEVB(W)058 0488 DEVB(W)088 2853 DEVB(W)029 1885 DEVB(W)059 0523 DEVB(W)089 2953 DEVB(W)030 1979 DEVB(W)060 0851 DEVB(W)090 3045 Reply Question Reply Question Reply Question Serial No. -

Legislative Council Brief

File Ref.: DEVB/CS/CR6/5/284 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL BRIEF Declaration of Ho Tung Gardens at 75 Peak Road as a Proposed Monument under the Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance INTRODUCTION After consultation with the Antiquities Advisory Board (AAB)1, the Secretary for Development (SDEV), in her capacity as the Antiquities Authority under the Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance (Chapter 53) (the Ordinance), has decided to declare Ho Tung Gardens (as delineated at Annex A) as a proposed monument under section 2A(1) of the Ordinance. The declaration will be published in the Gazette on 28 January 2011. JUSTIFICATIONS Heritage and architectural value 2. Ho Tung Gardens is on the list of 1 444 historic buildings2 in Hong Kong. On 25 January 2011, AAB confirmed the Grade 1 status of Ho Tung Gardens, taking account of the assessment of an independent expert panel as well as the views and information received during the public consultation period on the proposed gradings of the 1 444 historic buildings. A Grade 1 historic building by definition is a “building of outstanding merit, which every effort should be made to preserve if possible.” 3. Ho Tung Gardens, also known in Chinese as 曉覺園, comprises three buildings (including a basically two-storey main building in Chinese 1 AAB is an independent statutory body established under section 17 of the Ordinance to advise the Antiquities Authority on any matters relating to antiquities, proposed monuments or monuments or referred to it for consultation under section 2A(1), section 3(1) or section 6(4) of the Ordinance. 2 The Antiquities and Monuments Office (AMO) carried out from 2002 to 2004 an in-depth survey of 1 444 historic buildings in Hong Kong that were mostly built before 1950. -

Historic Building Appraisal 1 Tsang Tai Uk Sha Tin, N.T

Historic Building Appraisal 1 Tsang Tai Uk Sha Tin, N.T. Tsang Tai Uk (曾大屋, literally the Big Mansion of the Tsang Family) is also Historical called Shan Ha Wai (山廈圍, literally, Walled Village at the Foothill). Its Interest construction was started in 1847 and completed in 1867. Measuring 45 metres by 137 metres, it was built by Tsang Koon-man (曾貫萬, 1808-1894), nicknamed Tsang Sam-li (曾三利), who was a Hakka (客家) originated from Wuhua (五華) of Guangdong (廣東) province which was famous for producing masons. He came to Hong Kong from Wuhua working as a quarryman at the age of 16 in Cha Kwo Ling (茶果嶺) and Shaukiwan (筲箕灣). He set up his quarry business in Shaukiwan having his shop called Sam Lee Quarry (三利石行). Due to the large demand for building stone when Hong Kong was developed as a city since it became a ceded territory of Britain in 1841, he made huge profit. He bought land in Sha Tin from the Tsangs and built the village. The completed village accommodated around 100 residential units for his family and descendents. It was a shelter of some 500 refugees during the Second World War and the name of Tsang Tai Uk has since been adopted. The sizable and huge fortified village is a typical Hakka three-hall-four-row Architectural (三堂四横) walled village. It is in a Qing (清) vernacular design having a Merit symmetrical layout with the main entrance, entrance hall, middle hall and main hall at the central axis. Two other entrances are to either side of the front wall. -

2013 Policy Address Policy Initiatives of Development Bureau

CB(1)428/12-13(03) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL PANEL ON DEVELOPMENT 2013 Policy Address Policy Initiatives of Development Bureau INTRODUCTION The Chief Executive (CE) delivered his 2013 Policy Address on 16 January 2013. This paper elaborates on the policy initiatives of the Development Bureau (DEVB). OUR VISION 2. Our vision is to ensure adequate land supply and to build up a “land reserve” so as to meet future demands in a timely manner and improve people’s living space. It is also our vision to continue to invest in and manage infrastructure development to facilitate economic and sustainable development of Hong Kong. 3. We aim to create a safe and quality city through formulating and implementing policies in the areas of heritage conservation, greening, tree management and total water management; implementing measures in landslip prevention, flood prevention, and lifts and escalators safety; implementing a multi-pronged approach to enhance building safety; as well as expediting urban renewal to improve the built environment and achieve better utilisation of land resources to meet various development needs. NEW INITIATIVES (1) LAND SUPPLY (a) Increasing Supply of Housing Land in Short to Medium Term (i) Increasing Development Density and Streamlining Land Administration - 2 - 4. Increasing the development density of residential sites is a feasible way to enhance flat production. We are working closely with the Planning Department (PlanD) and other departments to increase the development density of unleased or unallocated residential sites as far as allowable in planning terms. Similar applications from private residential developments for approval of higher development density will also be positively considered. -

Development Bureau's Reply Letter

……一卅一、,,,,,,"~.,..,,..__..~,,,,.,…一 叫一一一 政府總部 Planning and Lands Branch 發展局 Development Bureau 規割地政科 Government Secretariat 香港海為添莫還二號 17,肘" Wl品 t Wing. Central Government Offic間, 政府總部因與十七撥 2 Tim Mei Avenuc. Tamar. Hong Kong 本局檔號 OUl' Ref. DEVB(PL-P) 50/19112 電話 Tel: 35098805 來函檔號 YourRef. 傳真 Fax: 28684530 Ms. Sheridan Burke President International Scientific Cornrnittee on Twentieth Century Heritage, ICOMOS Mr. Albe1't Dubler P1'esident Intèrnational Union of Architects, UlA Ms. Ana Tostões President Docornorno International c/o 78 Geo1'ge Street Redfern, NSW 2016 Australia 27 June 2012 Dear Ms. Burke, Mr. Dubler and Ms. Tostões, Urgent Request to Reconsider Redevelopment of Central Government Offices West Wing HongKong Thank you fo1' your lette1' of 12 June 2012 1:0 the Chief Executive, attaching the Governrnent Hill Concern Group's “Proposal fo1' He1'itage Alert Action fo1' the West Wing, Central Governrnent Offices on Governrnent Hill, Hong Kong SAR" and requesting the Hong Kong SAR Governrnent 1:0 reconsider the pl朋1:0 redevelop the West Wing of the I a、 former Centra1 Government Offices (CGO). We are authorised to rep1y to you on beha1f ofthe ChiefExecutive. First of all, we would like to 1et you know that weω'e greatly appreciative of your views on our pl個 fo 1' the former CGO. However, having read your Ietter, we are deeply èoncemed that your organisations' assessment might not have taken into full consideration Hong Kong's heritage conservation policy, the associated statutory and administrative systems at work, and the detai1s of the fonner CGO site and the th1'ee buildings on it, based on which ou1' current conservation cum redevelopment p1an has been drawn up. -

Review of Policy on Conservation of Built Heritage Public Consultation

CONTENTS Chairman’s Foreword 2 1. Background And Purpose 4 2. Protecting Historic Buildings 8 3. Resources For Protecting Historic Buildings 14 4. Public Participation In Built Heritage Conservation 20 Public Consultation 25 Feedback Form 26 Chairman’s Foreword Over the past ten years, the various projects and issues relating to heritage conservation have become a matter of increasing public concern, and the discussion of built heritage conservation is no longer just confined to a small group of people. In fact, the conservation of built heritage is of paramount importance to showcase the cultural and historical landscape of a city, foster a sense of belonging among the community and promote the soft power of urban development. Nevertheless, the concepts involved are not as readily comprehensible as something visible and tangible or our personal interests, and obviously pose a formidable obstacle to the further development of our heritage conservation policy. The Antiquities Advisory Board has all along been making recommendations to the Antiquities Authority for monument declaration and assessment on historic buildings in an open and professional manner. While some of the conservation decisions agreed upon have garnered wide recognition, others have triggered disagreement. For example, there may be disagreement on cases involving a historic building no matter whether it is public or privately-owned; whether it should be preserved or demolished; whether it should be closed or open to the public; whether it is seldom heard of or well known among the public; and whether it has caused controversy or not. When handling the outstanding cases, we surely continue to adhere to the established practice. -

List of the 1444 Historic Buildings with Assessment Results

List of the 1,444 Historic Buildings with Assessment Results (as at 9 Sept 2021) Page 1 Proposed Year of Construction / Remarks Number Name and Address 名稱及地址 Ownership Grading Restoration 備註 Grade 1 confirmed on 18 Dec 2009 Tsang Tai Uk, Sha Tin, N.T. 新界沙田曾大屋 1 Private Built 1847-1867 1 二○○九年十二月十八日確定為一級歷史建築 Combined with numbers 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 as one item and accorded with The Wai was built between Kat Hing Wai, Shrine, Kam Tin, Yuen Long, Grade 1 collectively on 31 Aug 2010 新界元朗錦田吉慶圍神廳 1 Private 1465 and 1487, the wall 2 二○一○年八月三十一日確定與編號3、4、5、6和7合併為一項, N.T. was 1662-1722. 並整體評為一級歷史建築 The Wai was built between Combined with numbers 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7 as one item and accorded with Kat Hing Wai, Entrance Gate, Kam Tin, 1465 and 1487, the wall Grade 1 collectively on 31 Aug 2010 3 新界元朗錦田吉慶圍圍門 1 Private Yuen Long, N.T. was 1662-1722, alias Fui 二○一○年八月三十一日確定與編號2、4、5、6和7合併為一項, Sha Wai (灰沙圍). 並整體評為一級歷史建築 The Wai was built between Combined with numbers 2, 3, 5, 6 and 7 as one item and accorded with Kat Hing Wai, Watchtower (northwest) and 新界元朗錦田吉慶圍炮樓 1465 and 1487, the wall Grade 1 collectively on 31 Aug 2010 4 1 Private Enclosing Walls, Kam Tin, Yuen Long, N.T. (西北)及圍牆 was 1662-1722, alias Fui 二○一○年八月三十一日確定與編號2、3、5、6和7合併為一項, Sha Wai (灰沙圍). 並整體評為一級歷史建築 The Wai was built between Combined with numbers 2, 3, 4, 6 and 7 as one item and accorded with Kat Hing Wai, Watchtower (northeast) and 新界元朗錦田吉慶圍炮樓 1465 and 1487, the wall Grade 1 collectively on 31 Aug 2010 5 1 Private Enclosing Walls, Kam Tin, Yuen Long, N.T. -

Former Central Government Offices Project Press Conference

Review of Heritage Conservation Work cum Former Central Government Offices Project Press Conference 14 June 2012 by Mrs Carrie Lam Secretary for Development Review “Cultural life is a key component of a quality city life. A progressive city treasures its own culture and history along with a living experience unique to the city. In recent years, Hong Kong people have expressed our passion for our culture and lifestyle. This is something we should cherish.” (extracted from para. 49 of the Chief Executive’s 2007-08 Policy Address in 2007) “We must …, maintain the impetus of infrastructural development while preserving our environmental qualities and preservation of our heritage ” (One of the five areas laid down by the Chief Executive in 22 his election-platform manifesto) Review (Cont’d) Demolishing Star Ferry Clock Tower and Queen’s Pier – 2006 and 2007 Queen’s Pier 33 Review (Cont’d) Attending Public Forum at Queen’s Pier – 29 July 2007 “Friends of Local Actions...have carried forward our conservation work to a great extent.” (extracted from the speech delivered by the Secretary for Development at the Public Forum at Queen’s Pier on 29 July 2007) “The concept of “development as primary consideration” is already out of fashion. As the Secretary for Development, my duty is to strike a balance between conservation and development, ensuring that they are not opposing forces. This difficult and challenging task is a challenging test to my capability. Nevertheless, it is a firm promise by the new term of the Government, which implements people-oriented policy and values public engagement. -

The Proposal to Declare Hung Lau, Near Shek Kok Tsui Village, Castle

For discussion BOARD PAPER on 28 February 2017 AAB/2/2017-18 MEMORANDUM FOR THE ANTIQUITIES ADVISORY BOARD THE PROPOSAL TO DECLARE HUNG LAU, NEAR SHEK KOK TSUI VILLAGE, CASTLE PEAK, TUEN MUN, NEW TERRITORIES AS A PROPOSED MONUMENT UNDER THE ANTIQUITIES AND MONUMENTS ORDINANCE PURPOSE This paper aims to seek Members’ advice on the proposed declaration of Hung Lau, near Shek Kok Tsui Village, Castle Peak, Tuen Mun, New Territories (as delineated at Annex A) as proposed monument under section 2A(1) of the Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance (Cap. 53) (the “Ordinance”). HERITAGE VALUE OF HUNG LAU Historical and architectural merits 2. Hung Lau is situated at the former Castle Peak Farm (“CPF”) (青山 農場) in Tuen Mun. CPF was originally owned by Li Ki-tong (李紀堂), a dedicated follower of Dr. Sun Yat-sen and a member of Hsing Chung Hui (or Xingzhonghui) (興中會), an anti-Qing revolutionary society. Between 1901 and 1911, CPF was used as a depot for weapon storage, a ground for manufacturing and experimentation of firearms for the contemplated uprisings, a place for meetings by the revolutionaries, and a haven for disbanded revolutionaries escaping from the Manchu vengeance. Hung Lau, located within the site of CPF, is a two-storey brick building blending Chinese and Western architectural characteristics. However, its exact construction year cannot be ascertained and the direct relationship between the building and revolutionary activities led by Dr. Sun Yat-sen cannot be 2 fully established. An appraisal on the historical and architectural values and photographs of Hung Lau are at Annex B and Annex C respectively. -

DEVB/CHO/1B/CR/59 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL BRIEF Proposed Non-In

File Ref.: DEVB/CHO/1B/CR/59 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL BRIEF Proposed Non-in-situ Land Exchange for the Preservation of No. 23 Coombe Road, Hong Kong INTRODUCTION At the meeting of the Executive Council on 27 March 2018, the Council ADVISED and the Chief Executive (“CE”) ORDERED that a non-in-situ land exchange be carried out with the owner of Rural Building Lot No. 731 (the “Existing Lot”) so that the owner will surrender the Existing Lot to the Government for preservation and revitalisation of the privately-owned Grade 1 historic building (commonly known as “Carrick”) at No. 23 Coombe Road (the “Building”) thereon while the Government will grant simultaneously a lot opposite to the Building (to be known as Rural Building Lot No. 1207) (the “New Lot”) to the owner for private residential development, subject to the basic terms and conditions set out in paragraph 11 below as well as payment of full market value premium. The Existing Lot is shown edged blue and the New Lot coloured pink on the plan at Annex A. JUSTIFICATIONS Heritage Value of the Building 2. Built in 1887 with gross floor area (“GFA”) of about 561 square metres, the Building is a private residence (photos at Annex B) with its first owner being John Joseph FRANCIS (1839-1901), who was prominent in civic affairs in a number of respects, in particular his efforts in investigating the issue of mui-tsai (妹仔) and in drawing up the rules for enacting the formation of Po Leung Kuk Incorporation Ordinance to offer protection of women and girls. -

HKLJ3-4 Chen Jianlin-Ho Tung Gardens(17102013)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by HKU Scholars Hub Ho Tung Gardens Saga and the Basis of Compensation under Title the Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance: A Comparative and Incentive Case Study on Regulatory Takings Author(s) Chen, J Citation Hong Kong Law Journal, 2013, v. 43 n. 3, p. 835-868 Issued Date 2013 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10722/196789 Rights Creative Commons: Attribution 3.0 Hong Kong License Ho Tung Gardens Saga and the Basis of Compensation Under The Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance: A Comparative and Incentive Case Study on Regulatory Takings ❒ Chen Jianlin* Regulatory schemes that mandate historical preservation for private property are increasingly common. This article employs the attempt to preserve Ho Tung Gardens as a case study to examine problems in the design of compensation measures for such schemes. The compensation provision of Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance (Cap 53) is ambiguously worded, and this article argues that this Ordinance provides compensation only for the additional costs associated with the maintenance of historical buildings and does not compensate owners for property value depreciation. However, this article also argues from an incentive perspective that adequate compensation should be provided to property owners for such depreciation to ensure that the government and the public duly account for the true costs of heritage conservation. In addition, adequate compensation eliminates the perverse incentives for owners to preemptively demolish historical buildings in order to avoid the regulatory regime. This article draws on similar legislative experiences in the UK to propose guidelines for reforming the compensation provision.