In the Circuit Court of the First Circuit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Power of Giving

THE POWER OF GIVING 2010 Annual Report HARNESSING HEMOGLOBIN CHRISTOPHER CHUN HEMOGLOBIN HERO Blood. It doesnʼt just help us to live our lives, but helps to give life to others. When itʼs needed, Hemoglobin Hero and donors like Christopher Chun come to the rescue! Hemoglobin Heroʼs iron-rich, oxygen-carrying protein is present in the red blood cells of donors like Christopher, who started giving blood in 1980 at his company drive. It wasnʼt until his mother became ill in 1990 that he made blood donation a lifesaving habit. “I saw blood in real terms, and I was inspired to give more often,” says the century donor with characteristic enthusiasm . “Now, giving blood is part of my routine. You donʼt have to be Superman to save a life!” PRESIDENT & CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE At Blood Bank of Hawaii, we need not look far to find heroes. We see them every day during a visit to our donor room, or to a Lifesaver Club, school or community drive. They represent all ages, ethnicities and walks of life. They roll up their sleeves and quietly engage in one of life’s most altruistic services – giving the gift of life. We are proud to know these extraordinary heroes, and to serve as the critical link between the donors and Hawaii’s hospitals. As new treatments and procedures help save more patients and improve the quality of their lives, the need for blood is more vital than ever. Hawaii’s volunteer blood donors enable the use of new therapies and technologies, and make recovery a reality for countless people. -

3086 Waialae Avenue HONOLULU, HI 96816

FOR LEASE > RETAIL SPACE 3086 Waialae Avenue HONOLULU, HI 96816 Delivery in Summer of 2020 St. Louis School And Chaminade University St. Louis Drive Waialae Avenue 2nd Avenue 3rd Avenue A brand new building to be delivered Summer of 2020 with a total of 2,600 SF of ground floor retail space and 2,900 SF of second floor office/retail space with ample parking. Great visibility and frontage on Waialae Avenue with two levels of parking. Kaimuki is a prime destination - high daytime office population, convenient shopping, and amazing restaurants and coffee shops! CATHY KONG (S) JD COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL SENIOR ASSOCIATE 220 S. King Street, Suite 1800 808 541 7392 Honolulu, HI 96813 [email protected] www.colliers.com/hawaii FOR LEASE > RETAIL SPACE 3086 Waialae Avenue HONOLULU, HI 96816 To Be Developed All plans are subject to any amendments approved by the relevant authority. Rendering and illustrations are artist’s impressions only and cannot be regarded as representations of facts. CATHY KONG (S) JD COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL SENIOR ASSOCIATE 220 S. King Street, Suite 1800 808 541 7392 Honolulu, HI 96813 [email protected] www.colliers.com/hawaii FOR LEASE > RETAIL SPACE 3086 Waialae Avenue HONOLULU, HI 96816 Ground Floor Plan Property Highlights Area Waialae TMK No. (1) 3-3-1-3 Zoning B-2 Base Rent Negotiable Operating Expenses $1.00 PSF/month (estimated) Percentage Rent 8% Second Floor Plan Term 5 years Size 500 to 2,600 SF Features & Benefits > Close proximity to schools, including the University of Hawaii, Chaminade University, Saint Louis, Iolani, Punahou, Mid-Pacific Institute, Saint Patrick, Sacred Hearts Academy, Kaimuki High School, and Ali’iolani Elementary School > Customer parking will be located on two levels > Over 281,358 people reside in a 5-mile radius of the center with an average annual household income of $94,878 > Kaimuki is home to well-known restaurants providing convenient options for East Oahu residents, including Kahala and Diamond Head residents CATHY KONG (S) JD COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL SENIOR ASSOCIATE 220 S. -

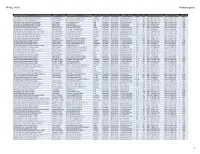

Food & Financial Donors

FOOD & FINANCIAL DONORS Please call (808) 537-6945 to make a food donation. To make a financial contribution, please visit our website www.alohaharvest.org or send to 3599 Waialae Avenue #23 Honolulu, HI 96816. FOOD DONORS AMERICAN BAR BEAU SOLEIL BURTON FAMILY 12 DAYS WITHOUT ASSOCIATION CATERING BUSINESS HUNGER AMERICAN EXPRESS BELT COLLINS INSURANCE 3660 ON THE RISE FINANCIAL BENJAMIN PARKER BUZZ STEAKHOUSE 54TH STREET DELI ADVISORS ELEMENTARY CR FOODS, INC. 7 ELEVEN NU’UANU II AMERICAN FRIENDS SCHOOL C&S WHOLESALERS A’ALA MEAT MARKET SERVICE BEST DRIVE-IN CABALSI FAMILY ABC DISNEY STUDIOS COMMIITTEE BEST FOODS CACKLE FRESH EGG ABC STORE #14 AMERICAN HAWAII BEST WESTERN FARM ABC STORE #17 CRUISES HONOLULU INTER. CAFENITY ABC STORE #31 AMERICAN HEART HOTEL CAKE COUTURE ABC STORE # 36 ASSOCIATION PLAZA HOTEL CALVARY CHAPEL ABC STORE #37 ANHEUSER-BUSCH BEYOND THE FOUR CENTRAL O‘AHU ABC STORE #38 ANNA MILLERS WALLS CALVIN KLEIN ABC STOR # 91 ANTOINETTE REBOSI BIG ISLAND CAMILLE ABE FAMILY APPETIZERS AND INC. STEAKHOUSE HENDERICKSON ABE LEE REALTY ARIA WILLIAMS BIG CITY DINER STYLIST ACOSTA ARMSTRONG PRODUCE BLANTON FAMILY CAMPBELL FAMILY ACTUS LEND LEASE LLC ASIAN AND PACIFIC BLESSED SACRAMENT CAMP ERDMAN/YMCA AFC SUSHI- ISLANDER AMERICAN CHURCH CANOES AT THE MAKIKI TIMES SCHOLARSHIP FUND BLISS A HAPPY PLACE ILIKAI WAIMALU TIMES ASSETS SCHOOL FOR DIABETICS CAPITOL ONE 360 AGNES PORTUGUESE ASSOCIATED BLUE WATER GRILL CARGO MEAT BAKE SHOP PRODUCERS BLUE TROPIX NIGHT COMPANY AGSALOG FAMILY ASTON WAIKIKI BEACH CLUB CARSON FAMILY AH LOO CATERING HOTEL BORDERS CAFE CASE, ED: REP. AHU ISA, LEI AUNTIE ANNIE’S BOSTON PIZZA – CASEY FAMILY AI OGATA PRETZELS KAIMUKI GROUP AIDELLS SAUSAGE CO. -

School Colors

SCHOOL COLORS Name Colors School Colors OAHU HIGH SCHOOLS & COLLEGES/UNIVERSITIES BIG ISLAND HIGH SCHOOLS Aiea High School green, white Christian Liberty Academy navy blue, orange American Renaissance Academy red, black, white, gold Connections PCS black, silver, white Anuenue High School teal, blue Hawaii Academy of Arts & Science PCS silver, blue Assets High School blue, white, red Hawaii Preparatory Academy red, white Campbell High School black, orange, white Hilo High School blue, gold Castle High School maroon, white, gold Honokaa High School green, gold Calvary Chapel Christian School maroon, gold Kamehameha School - Hawaii blue, white Christian Academy royal blue, white Kanu O Kaaina NCPCS red, yellow Damien Memorial School purple, gold Kau High School maroon, white Farrington High School maroon, white Ke Ana Laahana PCS no set colors Friendship Christian Schools green, silver Ke Kula O Ehukuikaimalino red, yellow Hakipuu Learning Center PCS black, gold Keaau High School navy, red Halau Ku Mana PCS red, gold, green Kealakehe High School blue, silver, gray Hanalani Schools purple, gold Kohala High School black, gold Hawaii Baptist Academy gold, black, white Konawaena High School green, white Hawaii Center for the Deaf & Blind emerald green, white Kua O Ka La NCPCS red, yellow, black Hawaii Technology Academy green, black, white Laupahoehoe Community PCS royal blue, gold Hawaiian Mission Academy blue, white Makua Lani Christian Academy purple, white Hoala School maroon, white Pahoa High School green, white Honolulu Waldorf School -

Governor's Emergency Education Relief (GEER) Awards by Name

Governor’s Emergency Education Relief (GEER) Awards by Name August 3, 2021 ASSETS • Project: Testing center for academic gaps due to COVID-19 • Description: Creating the state’s first pandemic-resistant learning support center that will provide evaluation/assessment of students and supports to overcome learning differences and reduce drop-out rates • Amount: $378,000 • Partners: o Public and private K-12 schools o University of Hawaiʻi o Hawaii Pacific University o Chaminade University Camp Mokuleʻia • Project: Mokuleʻia Mixed Plate Program • Description: Address issues of food insecurity by teaching Hawaii students how to grow and cook their own food • Amount: $300,000 • Partners: o Mohala Farms o Halau Waʻa o Chef Lars Mitsunaga Castle High School • Project: Ke Aloha O Na Noʻeau: Virtual and Interactive Performing Arts • Description: Create an afterschool statewide arts program that will deliver high quality, engaging educational opportunities that encourages student choice, promotes positive social and emotional connections through both in-person and online experiences, and addresses students’ need for creative and artistic outlets. • Award: $204,400 • Partners: o James B. Castle High School o Kaimukī High School August 3, 2021 Governor’s Emergency Education Relief (GEER) Awards by Name P. 2 o Nānākuli Intermediate & High School o Baldwin High School o The Alliance for Drama Education/T-Shirt Theatre Center for Tomorrow’s Leaders • Project: High School Leadership Development • Description: Build a 10-year pipeline to empower students -

Crossover Varsity Boys Wrestling Tournament

2014 OIA / ILH - CROSSOVER VARSITY BOYS WRESTLING TOURNAMENT INDIVIDUAL RESULTS 106 Lbs 113 Lbs 1st Cody Cabanban - Saint Louis High School (MD: 11-2) 1st Blaysen Terukina - Kamehameha - Kapalama (Fall ) 2nd Jayden Key Byrd - Kamehameha - Kapalama 2nd Jasper Cantorna - Pearl City High School 3rd 3rd Jordan Kannys - Kaiser High School (MD: 17-7) 4th 4th Ismael Membrere - McKinley High School 5th 5th Dallas Frederick - Waianae High School 6th 6th 7th 7th 8th 8th 120 Lbs 126 Lbs 1st Chance Ikei - Kaiser High School (TF: 16-0) 1st Alex Ursua - Pearl City High School (Fall ) 2nd Kawailani Somera Rickard - Leilehua High School 2nd Kealohi Graycochea - Kahuku High School 3rd Alika Agustin - Waianae High School (Fall ) 3rd Chevy Tabiolo Felicilda - Moanalua High School (Fall ) 4th Dayton Higa - Pearl City High School 4th Tysen Imai Toyama - Roosevelt High School 5th Braden Suzuki Scott - Kamehameha - Kapalama (Fall ) 5th Kai Nakamura - Roosevelt High School () 6th Jacob Asuncion - Kaimuki High School 6th 7th Baylen Cooper - Pearl City High School 7th 8th Mikala Gonsalves - Waianae High School 8th 132 Lbs 138 Lbs 1st Bishop Moore - Roosevelt High School (D: 13-6) 1st Kaeo Skeele - Kaiser High School (Fft) 2nd Sheldon Bailey - Waianae High School 2nd Makoa Freitas - Kamehameha - Kapalama 3rd Kaai Conradt - Kamehameha - Kapalama (D: 7-5) 3rd Alika Durham - Kaiser High School (D: 9-4) 4th Trevor Alvarado - Pearl City High School 4th Cullen Slavens - Kamehameha - Kapalama 5th Tyler Gutatala Gonzales - Kamehameha - Kapalama (Fall ) 5th Gage Simon - -

Kaimuki High 9%

Kaimuki High 2705 Kaimuki Avenue, Honolulu, Hawaii | Oahu | Kaimuki-McKinley-Roosevelt Complex Area THE STRIVE HI SCHOOL PERFORMANCE REPORT is an annual snapshot of a school’s performance on key indicators of student success. This report shows schools’ progress on the Department and Board of Education’s Strategic Plan and federally-required indicators under the Every Student Succeeds Act. These results help inform action for teachers, principals, community members, and other stakeholders. How are students performing in each subject? How many students are prepared for transition? Measures the percent of students meeting the standard/who are proficient on state assessments. Language Arts Math Science of 9th graders are promoted of students graduated 85% to 10th grade on-time 64% on-time -- 54% 54% 36% 13% 11% 12% of students completed a of students enrolled in 7% 21% 13% Career & Technical Education 47% postsecondary institutions 2015 2016 2017 2015 2016 2017 2015 2016 2017 program by 12th grade the fall after graduation How are students performing compared to others? Compares the percent of students meeting the standard/who are proficient on state assessments. Language Arts Math Science How many students missed 15 or more days of school this year? 2015 2016 2017 2017 58% 62% 42% 30% 36% 32% 11% 36% 31% 12% State: 19% State Complex School State Complex School State Complex School -- Area Area Area Complex Area: 18% How are student subgroups performing? 16% High Needs: English learners, economically disadvantaged, and students receiving Special Education services. Non-High Needs: All other students. Language Arts Math Do students feel safe at this school? 51% 30% 15% 9% 9% Measures student responses on the Safety dimension of the School Quality Survey. -

Learning Center Directory

LEARNING CENTERS Learning Center The Hawaii State Department of Education (DOE) Learning Centers (LC) are designed to expand educational opportunities for students with special talents and interests. A local variant of Directory the mainland magnet school concept, LC operate around a theme such as technology, performing arts, science, or communications arts. LC set high academic, behavioral and attendance expectations, and enable students to acquire and develop special talents and skills in-depth Although LC are primarily for high school students, some LC serve students in elementary and intermediate feeder schools through classes and programs usually offered outside of regular school hours. LC are open to students both in and out of the schools’ attendance area. Highly- skilled teachers offer classroom instruction and other learning experiences. HOW TO ENROLL The LC are open to all public school students who meet individual center requirements. Geographic Exceptions (GE) are available to students outside their attendance areas. Students may also remain at their home school and attend the LC part- time or after school. Parents should contact the LC of their choice for details, an application, and a GE form if applicable. Parents and students are responsible for their own transportation. Hawaii State Department of Education Office of Curriculum, Instruction and Student Support 1 Learning Centers by Type Business: Performing Arts: Kailua Community Quest Baldwin McKinley Castle Moanalua World Languages Hilo Waipahu Kahuku Music STEAM: -

Immunization Exemptions School Year 2018‐2019

Immunization Exemptions School Year 2018‐2019 HAWAII COUNTY School Religious Medical School Name Type Island Enrollment Exemptions Exemptions CHIEFESS KAPIOLANI SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 363 0.28% 0.00% CHRISTIAN LIBERTY ACADEMY 9‐12 PRIVATE HAWAII 46 2.17% 0.00% CHRISTIAN LIBERTY ACADEMY K‐8 PRIVATE HAWAII 136 0.00% 0.00% CONNECTIONS: NEW CENTURY PCS CHARTER HAWAII 349 14.04% 0.29% E.B. DE SILVA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 455 3.96% 0.00% HAAHEO ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 196 9.18% 0.00% HAILI CHRISTIAN SCHOOL PRIVATE HAWAII 117 4.27% 4.27% HAWAII ACADEMY OF ARTS & SCIENCE: PCS CHARTER HAWAII 672 2.38% 0.00% HAWAII MONTESSORI SCHOOL ‐ KONA CAMPUS PRIVATE HAWAII 7 0.00% 0.00% HAWAII PREPARATORY ACADEMY PRIVATE HAWAII 620 7.90% 0.00% HILO HIGH SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 1170 2.65% 0.17% HILO INTERMEDIATE SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 563 2.31% 0.00% HILO UNION ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 425 0.94% 0.00% HOLUALOA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 536 10.82% 0.37% HONAUNAU ELEMENTARY PUBLIC HAWAII 133 5.26% 0.00% HONOKAA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 404 3.71% 0.00% HONOKAA INTER &HIGH SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 615 2.11% 0.16% HOOKENA ELEMENTARY & INTER. PUBLIC HAWAII 110 4.55% 0.00% INNOVATIONS: PUBLIC CHARTER SCHOOL CHARTER HAWAII 237 16.88% 0.00% KA UMEKE KA EO: PCS CHARTER HAWAII 215 5.58% 0.00% KAHAKAI ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 750 5.87% 0.13% KALANIANAOLE ELEM. & INTER. SCHOOL PUBLIC HAWAII 307 2.28% 0.00% KAMEHAMEHA SCHOOLS ‐ HAWAII CAMPUS (9‐12) PRIVATE HAWAII 575 1.39% 0.00% KAMEHAMEHA SCHOOLS ‐ HAWAII CAMPUS (K‐8) PRIVATE HAWAII 580 1.72% 0.00% KANU O KA AINA SCHOOL: PCS CHARTER HAWAII 598 1.67% 0.00% KAU HIGH & PAHALA ELEM. -

Moanalua High School Parent Teacher Student Association Presents

The Honorees Our 2016 honorees are aptly described by the phrase, “the best of best.” Their professional accomplishments allow each of them to stand at the top of their fields as each has reached the pinnacle of success. Their life-long commitment to service-giving is indicative of why they are so deserving of the Kina’ole Award. It is our privilege to recognize each of these recipients for perpetuating the spirit of Kina’ole in all that they do. Carrie Sato began her 30 year teaching career in 1975 at Moanalua High School where she taught Social Studies and Japanese. She, along with Faye Chase, served as Co-Advisors for the MoHS Class of 1979. She later moved on to teach at Kaimuki High School, Niu Valley Middle School, and Kaiser High School. After 30 years in the classroom, she moved on to the DOE Administration as a State Office Teacher. She has a BA and M. Ed. From UH Manoa and recently earned her Ed. D. from USC in Educational Administration. She has been married to the same wonderful man for 45 years and became a grandmother in 2015. Gwen Mau began her teaching career in Seattle in 1974 and began teaching in Hawai’i in 1977. She came to MoHS in 1990, where she taught English and founded Moanalua’s first debate team. Prior to coming to Moanalua, she taught at several Oahu High Schools and in 1989 received the Leeward District Teacher of the Year. In 1992, she became the College and Career Counselor at MoHS. -

Draft Analysis of the Kalihi to Ala Moana School Impact District

DRAFT ANALYSIS OF THE KALIHI TO ALA MOANA SCHOOL IMPACT DISTRICT MAP 1: The Kalihi to Ala Moana District with Schools Serving the Area and the ½ mile Radius Around Each Rail Station Draft Analysis of the Kalihi to Ala Moana School Impact District This report was prepared in accordance with Act 245, Session Laws of Hawaii 2007, and Act 188, Session Laws of Hawaii 2010. The legislation is now codified in Chapter 302A, Sections 1601 to 1612, Hawaii Revised Statutes. The Board of Education must approve taking this report out to public hearing before final Board action. Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Section 1 – Introduction 2 Section 2 - Describing the Kalihi to Ala Moana School Impact District 6 Section 3 – Recent General Population Trends 7 Section 4 – Population Projections 10 Section 5 – Projected Growth Within the School Impact District 12 Section 6 – Conclusion 19 List of Appendices Appendix A – Enrollment at Kalihi to Ala Moana Schools 21 Appendix B – How the Impact Fee Formula Works 23 Appendix C – Requirements of the School Impact Fee Law 30 Appendix D – Act 188 Specified Classroom Report 35 Appendix E – Construction Cost Factors 42 List of Tables & Maps Map 1 – The Kalihi to Ala Moana District with Schools Serving the Area Cover and the ½ mile Radius Around Each Rail Station Map 2 – Elementary School Service Areas that make up the Boundaries for 5 the Kalihi to Ala Moana Impact Fee District Map 3 – Identification of Schools Adjacent to the Kalihi to Ala Moana Impact 20 Fee District Table 1 – Population Trends by County, Neighborhood -

Accreditation Status of Hawaii Public Schools

WASC 0818 Hawaii update Complex Area Complex School Name SiteCity Status Category Type Grades Enroll NextActionYear-Type Next Self-study TermExpires Central District-Aiea-Moanalua-Radford Complex Radford Complex Admiral Arthur W. Radford High School Honolulu Accredited Public School Comprehensive 9–12 1330 2020 - 3y Progress Rpt 2023 - 11th Self-study 2023 Central District-Aiea-Moanalua-Radford Complex Radford Complex Admiral Chester W. Nimitz School Honolulu Accredited Public School HI Public Elementary K–6 689 2019 - Mid-cycle 1-day 2022 - 2nd Self-study 2022 Windward District-Castle-Kahuku Complex Castle Complex Ahuimanu Elementary School Kaneohe Accredited Public School HI Public Elementary K–6 301 2020 - Mid-cycle 1-day 2023 - 2nd Self-study 2023 Central District-Aiea-Moanalua-Radford Complex Aiea Complex Aiea Elementary School Aiea Accredited Public School HI Public Elementary K–6 375 2020 - Mid-cycle 2-day 2023 - 2nd Self-study 2023 Central District-Aiea-Moanalua-Radford Complex Aiea Complex Aiea High School Aiea Accredited Public School Comprehensive 9–12 1002 2019 - 10th Self-study 2019 - 10th Self-study 2019 Central District-Aiea-Moanalua-Radford Complex Aiea Complex Aiea Intermediate School Aiea Accredited Public School Comprehensive 7–8 607 2020 - 8th Self-study 2020 - 8th Self-study 2020 Windward District-Kailua-Kalaheo Complex Kalaheo Complex Aikahi Elementary School Kailua Accredited Public School HI Public Elementary K–6 487 2021 - Mid-cycle 1-day 2024 - 2nd Self-study 2024 Honolulu District-Farrington-Kaiser-Kalani Complex