A Qualitative Study of the Process of Adoption, Implementation and Enforcement of Smoke-Free Policies in Privately-Owned Affordable Housing Michelle C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walkout Continues on Campus

#spartanpolls SPARTAN DAILY | SPECIAL SECTION Is it okay to harass public @spartandaily fi gures while they are shopping? In stands Thursday, March 23 11% Yes )LQGRXU*HRˉOWHURQ6QDSFKDW 89% No 114 votes - Final results FOLLOW US! /spartandaily @SpartanDaily @spartandaily /spartandailyYT Volume 148. Issue 24www.sjsunews.com/spartan_daily Wednesday, March 22, 2017 PROPOSED TUITION HIKE Walkout continues on campus BY MARGARET GUTIERREZ recruit and hire more faculty STAFF WRITER and student advisers. As a result of the increase in teaching staff, In response to proposed tuition the universities would be able to hikes, San Jose State students offer more classes, which would rallied on campus Tuesday to help increase graduation times for protest the tuition increases and students if the hikes pass. voice their concerns about the “I feel it is ridiculous,” said potential impact they could have Luis Cervantes Rodriguez, on students. A.S. director of community The California State University and sustainability affairs and Board of Trustees met at its board environmental studies senior. meeting on Tuesday. Among “The whole point to raising the topics of discussion was a tuition is to help the student’s proposal to raise tuition at all success and graduation rates. But California State Universities for it doesn’t make sense to me as a the 2017-2018 academic year. student that they are increasing “[For] people that don’t know someone’s tuition.” about it, it’s a way to create Several students voiced concerns awareness,” said psychology for minority and low-income junior Maria Gutierrez. “It’s a students. The statements made way to show our administration by CSU on its website, however, or chancellors, the people that are indicate that the proposed tuition there with the power, know that increase would not affect 60 it’s affecting us. -

Fixtures & Finishes

Fixtures & Finishes Move-up Home 2021 CONTENTS FOUNDATION, STRUCTURE & EXTERIOR 4 ELECTRICAL & LIGHTING 5 WINDOWS & DOORS 5 Fall in love with HEATING, COOLING & INSULATION 6 PLUMBING 7 your new home. INTERIOR FINISHES 8 PAINT 10 CABINETRY & COUNTERTOPS 10 APPLIANCES 11 SMART HOME 12 WARRANTY 15 SAFETY 15 Yourhas a solidHome foundation to stand on. Light & Bright FOUNDATION, STRUCTURE & EXTERIOR: ELECTRICAL & LIGHTING: WINDOWS & DOORS: • Choose light fixtures from our lighting packages • Damp proofing with asphalt coating applied to the • Precast concrete exterior steps to your front entry • Insulated garage overhead door opener comes exterior surface of the foundation walls • Recessed exterior pot lights in the main floor soffits with WiFi, wall mount control with two remotes, and • The driveway, front steps and walkway leading to your child protection sensors along with keyless entry • Engineered rim beams, floor joists and roof truss front door will be sealed with an advanced concrete • Kitchen, great room, hallways and bonus room system sealer lighting includes LED pot lights in warm white light • All main and second floor windows are triple pane, low-e argon filled windows • Subfloor is tongue and groove as well as glued and • Vinyl siding is installed over Tyvek house wrap • LED lights in warm white in all light fixtures screwed for additional support including exterior coach light • Insulated front door with a peephole or glass insert • 9’ ceiling height on the main floor • Wall studs at 24” on center for limited heat transfer • Dimmable LED bulbs in all main and second floor • Weiser Smart Key deadbolt on exterior door lights • Lifetime fiberglass laminated (double layered) shingle • Dual pane sliding glass door in the dining room system • USB outlet located in the kitchen • All windows and doors are protected with building • TV and data outlets located in the great room envelope sealant for moisture control 4 5 Essentials, including K eeps in theyou winter,cozy the kitchen sink. -

Drake Album 2012 Mp3

Drake album 2012 mp3 Buy Take Care (Album Version) [Explicit]: Read 31 Digital Music Reviews Original Release Date: November 15, ; Release Date: March 20, Love Rihanna hence buying the MP3 of this particular song and no Drake album. Buy The Zone (Album Version (Explicit)) [feat. Drake] [Explicit]: Read 7 Digital Music Reviews - Zone (Album Version (Explicit)) [feat. Drake] [Explicit Add to MP3 Cart. Song in MP3 . BySirenia Avelaron November 25, Find a Drake - Take Care first pressing or reissue. Complete your Drake collection. Shop Vinyl 18 × File, MP3, Album, kbps, Explicit. Country: Notes. © Cash Money Records / Young Money Ent. / Universal Rec. Kaufen Sie die CD für EUR 5,99, um die MP3- Version kostenlos in Ihrer Musikbibliothek zu speichern. Dieser Service ist für Geschenkbestellungen nicht. Drake shares 4 new songs for download, new album release date MP3: New Drake - "Headlines" · By Pretty Drake Spring Tour Dates. Eminem - No Return ft. Drake HQ (NEW ALBUM).mp3. Sam Honey Please try again later. Take Care (Album Version) [feat. Rihanna] [Explicit]: Drake: : MP3 Downloads. Take Care (Deluxe) [Explicit]: Drake: : MP3 Downloads. Buy the CD album for £ and get the MP3 version for FREE. .. ; Label: Universal-Island Records Ltd. Copyright: ℗© Cash Money Records Inc. Record. List of songs with Songfacts entries for Drake. List of songs by Drake. 0 to / The Catch Up · 10 Bands · to My City · 5AM In Toronto · 6 God · 6 Man. Listen to songs from the album Take Care (Deluxe Version), including In , while on tour, Drake announced that he had started work on. Here's a list of the 20 best Weeknd songs to date. -

Cochecho Arts Festival Continues This Week

In This Issue: Friday, July 27, 2018 Cochecho Arts Festival continues Dover Fire and Rescue offering free smoke alarms and carbon monoxide detectors City of Dover seeks Ward 2 moderator Road closures and parking restrictions in place for Saturday road race City to hold informational meeting on Whittier Street sidewalks Woodman Museum now recruiting cast members for "Lives & Legends" weekend over Listens to host 'Community Connection' during Dover Night Out City of Dover and surrounding Cochecho Arts Festival towns to hold Hazardous continues this week Waste Collection Day Walking tours of historic Dover The 32nd annual Cochecho Dover's 400th Anniversary Arts Festival continues this Celebration Committee week, beginning with tonight's headliner performance at the Discover Dover with Peek at Rotary Arts Pavilion, Henry Law Park. The show opens the Week with Slack Tide Trio, part of the Federal Savings Bank Friday Night Openers series. Taking the stage at 7 p.m. is Groupo Fantasia, part of the Liberty Mutual Headliner series, and sponsored by Dupont's Service Center. Meetings this week: Angel Wagner formed Grupo Fantasia in 1993 with To view televised meetings musicians from his native Dominican Republic and other online, on demand, visit Latin American countries. Many years and many awards www.dover.nh.gov/dntv later, they continue to bring the very best in Latin music to New England and beyond. For a complete list of upcoming meetings visit The festival lineup for the week includes: the meeting calendar page. Tuesday, July 31, 10:30 a.m.: Rob Duquette, Rotary Arts Pavilion, part of the Amtrak Downeaster Children's Series Spotlight and sponsored by Northeast Delta Dental; Wednesday, Aug. -

January-February 2020

Maplewood Senior Echo Maplewood Senior Center Please join us for a Valentine’s Day Po-Ke-No Lunch-n-Learn presented by Michigan Legacy Credit Union Monday, February 10, 2020 Financial Fraud & 1:00pm Scam Protection Please join us for Valentine’s Day cupcakes, Tuesday, January 28, 2020 punch and Po-Ke-No 12:30pm This event will be held in This is a free event sponsored the Community Room at by the Maplewood Senior the Maplewood Center Thrift Shop Community Center PO-KE -NO at the Maplewood Senior Center Join us the 1st Monday of every month! 1:00pm Community Room January 6th February 3rd March 2nd April 6th Sponsored by Medilodge of Farmington January/February 2020 MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 1 CLOSED 2 3 4 Aerobics 8:45am Senior Fitness Room Senior Fitness Room Senior Fitness Room 8:45am-5:00pm 9:30am-4:00pm Focus Hope Food 8:45am-7:00pm Yoga 5:30pm-6:30pm Friday Commodities T.O.P.S. 10am-11am Senior Lunch 12pm January 10th 3rd Wednesday Bingo 1pm January 15th Cardio Drumming 6:45pm-7:45pm 6 7 8 9 10 11 Senior Fitness Room Aerobics 8:45am Senior Fitness Room Aerobics 8:45am Senior Fitness Room Senior Fitness Room 8:45am-7:00pm Senior Fitness Room 8:45-7:00pm Senior Fitness Room 8:45am-5:00pm 9:30am-4:00pm Thrift Shop 9am-2pm 8:45am-7:00pm Thrift Shop 9am-2pm 8:45am-7:00pm Yoga 5:30pm-6:30pm HOPE Dementia Senior Lunch 12pm Thrift Shop 9am-2pm Club #1 9am Thrift Shop 9am-2pm Education 10am Po-Ke-No 1pm Arthritis Exercise 10:30a Senior Lunch 12pm T.O.P.S. -

Issue 7 (July)

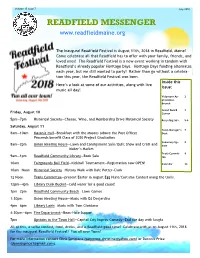

Volume 15 Issue 7 July 2018 READFIELD MESSENGER www.readfieldmaine.org The Inaugural Readfield Festival is August 11th, 2018 in Readfield, Maine! Come celebrate all that Readfield has to offer with your family, friends, and loved ones! The Readfield Festival is a new event working in tandem with Readfield’s already popular Heritage Days. Heritage Days funding alternates each year, but we still wanted to party! Rather than go without a celebra- tion this year, the Readfield Festival was born. Inside this Here’s a look at some of our activities, along with live issue: music all day! Volunteer Ap- 2 preciation Brunch Select Board 3 Friday, August 10 Corner 5pm—7pm Historical Society—Cheese, Wine, and Membership Drive Historical Society Recycling Info. 5-6 Saturday, August 11 Town Manager’s 7 8am—10am Masonic Hall—Breakfast with the Masons (above the Post Office) Desk Proceeds benefit Class of 2020 Project Graduation Cemetery Up- 8 8am—2pm Union Meeting House—Lawn and Consignment Sale/Quilt Show and Craft and date Maker’s Market Trails Commit- 9 9am—1pm Readfield Community Library—Book Sale tee 10am Fairgrounds Ball Field—Kickball Tournament—Registration now OPEN! Calendar 23 10am—Noon Historical Society—History Walk with Dale Potter-Clark 12 Noon Trails Committee—present Easter in August Egg Hunt/Costume Contest along the trails. 12pm—4pm Library Dunk Bucket—Cold water for a good cause! 1pm—2pm Readfield Community Beach—Lawn Games 1:30pm Union Meeting House—Music with Ed Desjardins 4pm—6pm Library Lawn—Music with Tom Giordano 4:30pm—6pm Fire Department—Bean-Hole Supper 7pm Upstairs in the Town Hall—Capital City Improv Comedy—End the day with laughs All of this, a selfie contest, food, drinks, and a Readfield good time! Celebrate with us on August 11th, 2018 for the inaugural Readfield Festival! Fun all over Town! For more information contact Chris Sammons ([email protected]) or Dennnis Price ([email protected]). -

April 2018 Text Version

Well Now... wellbeing Newsletter APRIL 2018 Keeping you up to date. CAPOD | The University Of St Andrews | No SC013532 Well Useful Now... Organisations and Websites St Andrews wellbeing Hello, I'm Callum, the Health and Fitness webpages Manager at the University Sports Centre, and I'm one of two representatives from the Department British Heart Foundation of Sport and Exercise on the Wellbeing & NHS Engagement Group. Smoking Helpline It gives me great pleasure to introduce the April Drink Aware edition of the Well Now Newsletter. This month's theme is Cancer Awareness. I'm sure WSalenet pto c qenutitr?e We have 10 free most of us know or have known people close to copies of Allen us who have had a form of cancer at some point Alzheimer Scotland Carr's book to give in their life. You may not know that the University away - get yours by LGBeTm- Faoiulindg ation Sport Centre work with Fife Leisure Trust to wellgrp @st- deliver Active Options and Move More classes. Staenpd Creowuns.ta Cc.huakl loern ge These classes are specially for referral patients, calling Ex t: 2533 some whom are undergoing treatment or Svaroopa Yoga recovering from cancer. Please feel free to check MIND - Mental Wellbeing our website or email me on cgk@st- 0845 766 0163 andrews.ac.uk for more details. Click on this link Please read the information in this issue and take to access these useful advantage of the Macmillan Mobile Unit sites: Information visit to St Andrews on 10th April, or https://tinyurl.com/ydgf33hc the Lab Talk & Tour on the 21st. -

AUSTRALIAN SINGLES REPORT 3Rd April, 2017 Compiled by the Music Network© FREE SIGN UP

AUSTRALIAN SINGLES REPORT 3rd April, 2017 Compiled by The Music Network© FREE SIGN UP ARTIST TOP 50 Combines airplay, downloads & streams #1 SINGLE ACROSS AUSTRALIA shape of you 1 Ed Sheeran | WMA shape of you something just like this Ed Sheeran | WMA 2 The Chainsmokers & Coldp... all time low 3 Jon Bellion | EMI Following on from the new peak achieved last week, Jon Bellion manages to do it at again, hitting paris higher reaches of the chart at #3 from #5 with All Time Low. Now he’s only got Ed Sheeran and The 4 The Chainsmokers | SME Chainsmokers & Coldplay collaboration to deal with… castle on the hill 5 Ed Sheeran | WMA Norwegian duo Stargate crack the Top 10 with Waterfall ft. P!nk & Sia, planting their flag on a new don't leave peak at #7 from #36. Waterfall is being chased by Martin Garrix’s Scared To Be Lonely ft. Dua Lipa, 6 Snakehips | SME also at a new peak at #9 from #12. waterfall 7 Stargate | SME Two new debuts crack the Top 20 this week. The first, at #10, is Drake’s Passionfruit, which has proven i don't wanna live forever to be the radio favourite from More Life. The other is at #18 with Clean Bandit’s Symphony ft. Zara 8 ZAYN & Taylor Swift | UMA Larsson, the Most Added Song To Radio two weeks ago. scared to be lonely 9 Martin Garrix | SME passionfruit 10 Drake | UMA Touch #1 MOST ADDED TO RADIO 11 Little Mix | SME galway girl still got time 12 Ed Sheeran | WMA ZAYN ft. -

City Lights Oct. 2017.Pdf

October, 2017 www.desototexas.gov DeSoto City Lights A Publication of the City of DeSoto Community Relations Department DeSoto Economic Development Corporation Partners with Options Real Estate to “Grow DeSoto” The City Council and Economic Development Corporaon recognize the need to grow DeSoto business opportunies for residents with unique retail ideas. When faced with the empty space le when the Westlake Ace Hardware closed, they envisioned creang a space that would assist small business owners with establishing viable businesses, while providing a unique retail environment for the community. They reached out to the property owner, Monte Anderson, and asked him to consider alternaves for the space. As owner of Opons Real Estate, Anderson thrives on shaking up the real estate market with new and innovave ideas. He accepted their challenge and proposed the Grow DeSoto business incubator project as a means to address the needs of new and developing businesses. The Grow DeSoto business incubator is a 26,000 square foot retail building located at 320 E. Belt Line Road that will contain a variety of restaurants, retail spaces and shared workspace. Food trailers will also be staoned in the parking lot of the shopping center for patrons to enjoy. “The project is intended to allow entry level entrepreneurs a place to start at a very low cost and with low risk,” said Anderson. “We are looking for authenc local entrepreneurs who have the dream and a desire to build local wealth. We want to give people an opportunity to build assets and value in order to someday own their own small buildings.” Many small businesses need a lower entry to market. -

Alice Cooper/ Welcome’ to His Era

ALICE COOPER/ WELCOME’ TO HIS ERA Gamble, Huff, McCartney Each Win Four 1975 BMI Awards Part 3 In A Series On Disk Buying Habits More Pirated Tapes Seized Signings: Carmen McCrae To Blue Note; Trini Lopez To Private Stock R&B Hits The Financial Page (Ed) From a hard-core of fanaticfans, theirfame hasspread nationwide. 30,000 fans at Boston Garden. Already sold-out 45,000 more in Detroit.“GetYour Wings”is gold. ‘Aerosmith”is nudgingthe 24k mark. Their newest album, Toys in the Attic," ' J pc 33479* 1 has bulleted to their career high, 16? ata rate matched only bytheir sing!e“Sweet Emotion.” ,» Aerosmith. They’re making it big. On Columbia Records and Tapes. ‘Produced by Jack Douglas for Waterfront Productions Limited and Contemporary Communications Corporation 'D' "COLUMBIA," §?] MARCASREG. ©1975CBSINC. THE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC-RECORD WEEKLY VOLUME XXXVII — NUMBER 4 — June 14, 1 975 r \ GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher cashboxeditorial MARTY OSTROW Executive Vice President ED ADLUM R&B Hits The Financial Page Managing Editor Editorial in a top ten of a different sort — a listing of the nation’s largest black owned DAVID BUDGE Editor In Chief and black managed business — comes heartening confirmation of the IAN DOVE healthy state of black music. East Coast Editorial Director New York The listing, compiled by Black Enterprises magazine in New York, has the STEVE MARKS BARRY TAYLOR nfiighty Motown Industries secure as the no. 1 black business with $45 million BOB KAUS Hollywood in sales in 1974, $1 1 million ahead of its nearest competitor. PHIL ALEXANDER No surprise here, Barry Gordy's record and film complex has been the JESS LEVITT MARC SHAPIRO frontrunner on this list for the last three years. -

Loyola University New Orleans PRSSA Bateman Team

2015 PRSSA Bateman Case Study Competition Loyola University New Orleans PRSSA Bateman Team Created by: Faculty Advisor: Katherine Collier Cathy Rogers, Ph.D. Chelsea Cunningham Kenneth Motley Professional Advisor: Martin Quintero Jeffrey Ory, APR, ABC NiRey Reynolds TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Research 1 Target Audiences 3 Key Messages 4 Challenges and Opportunities 4 Objectives 4 Strategies, Rationales & Tactics 5 Evaluation 8 Conclusion 10 Appendix 12 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Home is where it all starts. It’s barbecues in the backyard and inviting neighbors over for a good time. It’s second-lining down the street and a hot bowl of gumbo. Home is where we lay our heads at night. It’s tucking the little ones in at night and checking for monsters under the bed. It should be safe, comfortable and stable. Too often, however, people don’t have access to nutritious meals, spots in the best schools or protected environments free from harm. In support of the national Home Matters movement, the 2015 Loyola Univer- sity New Orleans PRSSA Bateman campaign Geaux Home: Home is the bedrock of success, partnered with two local Home Matters supporters to show New Orleanians how home contributes to success and impacts education, health, public safety and economic development. Geaux Home established the link between home and these core social issues and emphasized the need to redefine the American Dream. Geaux Home accelerated action and conversation about housing in New Orleans through community outreach and instigation of policy change. We raised awareness of Home Matters through our 18 presentations, partnerships with Providence Community Housing and Make It Right Foundation and our Geaux to Jazzfest social media contest. -

Sixteen-Week Academic Calender Looms in the Distance for Students

CERRITOS COLLEGE WWW.TALONMARKS.COM WEDNESDAY, MARCH 29, 2017 VOLUME 61, NO. 17 FIRST ISSUE FREE, ADDITIONAL COPIES $1 Disadvantages: 1. The greatest disadvantage of adopting a compressed calendar is cost. 2. Another concern is that those students who benefit from a longer semester will have poorer success and retention. This report’s analysis of success and reten- tion, however, provides evidence that, as a whole, stu- dent success and retention is not harmed by course compression. 3. Some programs will need to alter how lectures, labo- ratories, and practicums are scheduled. Nursing and Cosmetology are examples of programs that will be affected in this way. However, every college in our region has been able to adapt successfully. Cerritos College should be able to, as well. Advantages: 1. The major on-going expense of the compressed cal- endar arises from the need to reinstitute the Weekend College, something the 2009 Report did not need to consider. However, the Weekend College would serve Perla Lara/TM Photo illustration of a possible 16 week acaemic calendar and greatly benefit a significant, non-traditional stu- dent population. 2. By including a winter intercession, the college can Sixteen-week academic calender utilize facilities more efficiently. It will relieve some of the pressure for classroom space during the primary (fall/spring) sessions. 3. The addition of the winter intercession provides looms in the distance for students more flexibility for student schedules. 4. A winter intercession also provides an opportunity Monique Nethington The board will hear the proposal about the idea. the additional cost for the school.