Clinical Presentation, Diagnostic Findings and Long-Term Survival In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BSE Welsh Springer Spaniel.Pmd

AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL KENNEL COUNCIL Extended Breed Standard of THE WELSH SPRINGER SPANIEL Produced by Welsh Springer Spaniel Club of NSW Inc. in conjunction with The Australian National Kennel Council Standard adopted by Kennel Club London 1994 Standard adopted by ANKC 1994 FCI Standard No: 5 Breed Standard Extension adopted by the ANKC 2008 Copyright Australian National Kennel Council 2008 Country of Origin ~ United Kingdom Extended Standards are compiled purely for the purpose of training Australian judges and students of the breed. In order to comply with copyright requirements of authors, artists and photographers of material used the contents must not be copied for commercial use or any other purpose. Under no circumstances may the Standard or Extended Standard be placed on the Internet without written permission of the Australian National Kennel Council Photo of a top winning UK bitch regarded by many breeders as one of the best Welsh Springers ever shown. Taken from Ref. ( 5 ) . HISTORY OF THE WELSH SPRINGER SPANIEL The Welsh Springer Spaniel is described in the standard as a very ancient and distinctive breed of pure origin. Spaniels are considered one of the oldest dogs known to man. They appear to have been in Europe for centuries and are thought to have originated in Spain and arrived in England during the Dark Ages. It is speculated that red and white spaniels were in Wales in the 6th century. Red and white tracking dogs were recorded in Wales in the 11th century in a passage in the Mucinogen, a book describing Welsh folklore. The term Spaniel was first used by Chaucer (1340-1400). -

Download Olde English Bulldogge Breed Standard

Olde English Bulldogge Official UKC Breed Standard Guardian Dog Group Revised April 2, 2018 ©Copyright 2013, United Kennel Club The goals and purposes of this breed standard include: GENERAL APPEARANCE to furnish guidelines for breeders who wish to maintain The Olde English Bulldogge is a muscular, medium sized the quality of their breed and to improve it; to advance dog of great strength, and possessed of fluid, agile this breed to a state of similarity throughout the world; movement. He is well balanced and proportioned, while and to act as a guide for judges. appearing capable of performing without any breathing Breeders and judges have the responsibility to avoid restrictions in either heat or in cold. any conditions or exaggerations that are detrimental to Disqualifications: Unilateral or bilateral cryptorchid. the health, welfare, essence and soundness of this breed, and must take the responsibility to see that CHARACTERISTICS these are not perpetuated. The disposition of the Olde English Bulldogge is Any departure from the following should be confident, friendly and alert. An OEB should be an considered a fault, and the seriousness with which the animated and expressive dog, both in and out of the fault should be regarded should be in exact proportion show ring. to its degree and its effect upon the health and welfare Fault: Shyness in a mature dog. of the dog and on the dog’s ability to perform its Disqualification: Viciousness or extreme shyness. traditional work. Absolute soundness and proper muscle tone is a HEAD must. Head properties should remain free of Serious Faults: Excessive wrinkle, lack of pigment exaggeration so as to not compromise breathing and/or around eyes, nose or mouth. -

Molosser Dogs: Content / Breed Profiles / American Bulldog

Molosser Dogs: Content / Breed Profiles / Americ... http://molosserdogs.com/e107_plugins/content/c... BREEDERS DIRECTORY MOLOSSER GROUP MUST HAVE PETS SUPPLIES AUCTION CONTACT US HOME MEDIA DISCUSS RESOURCES BREEDS SUBMIT ACCOUNT STORE Search Molosser Dogs show overview of sort by ... search by keyword search Search breadcrumb Welcome home | content | Breed Profiles | American Bulldog Username: American Bulldog Password: on Saturday 04 July 2009 by admin Login in Breed Profiles comments: 3 Remember me hits: 1786 10.0 - 3 votes - [ Signup ] [ Forgot password? ] [ Resend Activation Email ] Originating in 1700\'s America, the Old Country Bulldogge was developed from the original British and Irish bulldog variety, as well as other European working dogs of the Bullenbeisser and Alaunt ancestry. Many fanciers believe that the original White English Bulldogge survived in America, where Latest Comments it became known as the American Pit Bulldog, Old Southern White Bulldogge and Alabama Bulldog, among other names. A few regional types were established, with the most popular dogs found in the South, where the famous large white [content] Neapolitan Mastiff plantation bulldogges were the most valued. Some bloodlines were crossed with Irish and Posted by troylin on 30 Jan : English pit-fighting dogs influenced with English White Terrier blood, resulting in the larger 18:20 strains of the American Pit Bull Terrier, as well as the smaller variety of the American Bulldog. Does anyone breed ne [ more ... Although there were quite a few "bulldogges" developed in America, the modern American Bulldog breed is separately recognized. ] Unlike most bully breeds, this lovely bulldog's main role wasn't that of a fighting dog, but rather of a companion and worker. -

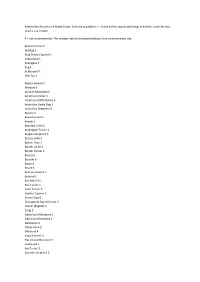

Dog Breeds Impounded in Fy16

DOG BREEDS IMPOUNDED IN FY16 AFFENPINSCHER 4 AFGHAN HOUND 1 AIREDALE TERR 2 AKITA 21 ALASK KLEE KAI 1 ALASK MALAMUTE 6 AM PIT BULL TER 166 AMER BULLDOG 150 AMER ESKIMO 12 AMER FOXHOUND 12 AMERICAN STAFF 52 ANATOL SHEPHERD 11 AUST CATTLE DOG 47 AUST KELPIE 1 AUST SHEPHERD 35 AUST TERRIER 4 BASENJI 12 BASSET HOUND 21 BEAGLE 107 BELG MALINOIS 21 BERNESE MTN DOG 3 BICHON FRISE 26 BLACK MOUTH CUR 23 BLACK/TAN HOUND 8 BLOODHOUND 8 BLUETICK HOUND 10 BORDER COLLIE 55 BORDER TERRIER 22 BOSTON TERRIER 30 BOXER 183 BOYKIN SPAN 1 BRITTANY 3 BRUSS GRIFFON 10 BULL TERR MIN 1 BULL TERRIER 20 BULLDOG 22 BULLMASTIFF 30 CAIRN TERRIER 55 CANAAN DOG 1 CANE CORSO 3 CATAHOULA 26 CAVALIER SPAN 2 CHESA BAY RETR 1 CHIHUAHUA LH 61 CHIHUAHUA SH 673 CHINESE CRESTED 4 CHINESE SHARPEI 38 CHOW CHOW 93 COCKER SPAN 61 COLLIE ROUGH 6 COLLIE SMOOTH 15 COTON DE TULEAR 2 DACHSHUND LH 8 DACHSHUND MIN 38 DACHSHUND STD 57 DACHSHUND WH 10 DALMATIAN 6 DANDIE DINMONT 1 DOBERMAN PINSCH 47 DOGO ARGENTINO 4 DOGUE DE BORDX 1 ENG BULLDOG 30 ENG COCKER SPAN 1 ENG FOXHOUND 5 ENG POINTER 1 ENG SPRNGR SPAN 2 FIELD SPANIEL 2 FINNISH SPITZ 3 FLAT COAT RETR 1 FOX TERR SMOOTH 10 FOX TERR WIRE 7 GERM SH POINT 11 GERM SHEPHERD 329 GLEN OF IMALL 1 GOLDEN RETR 56 GORDON SETTER 1 GR SWISS MTN 1 GREAT DANE 23 GREAT PYRENEES 6 GREYHOUND 8 HARRIER 7 HAVANESE 7 IBIZAN HOUND 2 IRISH SETTER 2 IRISH TERRIER 3 IRISH WOLFHOUND 1 ITAL GREYHOUND 9 JACK RUSS TERR 97 JAPANESE CHIN 4 JINDO 3 KEESHOND 1 LABRADOR RETR 845 LAKELAND TERR 18 LHASA APSO 61 MALTESE 81 MANCHESTER TERR 11 MASTIFF 37 MIN PINSCHER 81 NEWFOUNDLAND -

Table & Ramp Breeds

Judging Operations Department PO Box 900062 Raleigh, NC 27675-9062 919-816-3570 [email protected] www.akc.org TABLE BREEDS SPORTING NON-SPORTING COCKER SPANIEL ALL AMERICAN ESKIMOS ENGLISH COCKER SPANIEL BICHON FRISE NEDERLANDSE KOOIKERHONDJE BOSTON TERRIER COTON DE TULEAR FRENCH BULLDOG HOUNDS LHASA APSO BASENJI LOWCHEN ALL BEAGLES MINIATURE POODLE PETIT BASSET GRIFFON VENDEEN (or Ground) NORWEGIAN LUNDEHUND ALL DACHSHUNDS SCHIPPERKE PORTUGUSE PODENGO PEQUENO SHIBA INU WHIPPET (or Ground or Ramp) TIBETAN SPANIEL TIBETAN TERRIER XOLOITZCUINTLI (Toy and Miniatures) WORKING- NO WORKING BREEDS ON TABLE HERDING CARDIGAN WELSH CORGI TERRIERS MINIATURE AMERICAN SHEPHERD ALL TERRIERS on TABLE, EXCEPT those noted below PEMBROKE WELSH CORGI examined on the GROUND: PULI AIREDALE TERRIER PUMI AMERICAN STAFFORDSHIRE (or Ramp) PYRENEAN SHEPHERD BULL TERRIER SHETLAND SHEEPDOG IRISH TERRIERS (or Ramp) SWEDISH VALLHUND MINI BULL TERRIER (or Table or Ramp) KERRY BLUE TERRIER (or Ramp) FSS/MISCELLANEOUS BREEDS SOFT COATED WHEATEN TERRIER (or Ramp) DANISH-SWEDISH FARMDOG STAFFORDSHIRE BULL TERRIER (or Ramp) LANCASHIRE HEELER MUDI (or Ramp) PERUVIAN INCA ORCHID (Small and Medium) TOY - ALL TOY BREEDS ON TABLE RUSSIAN TOY TEDDY ROOSEVELT TERRIER RAMP OPTIONAL BREEDS At the discretion of the judge through all levels of competition including group and Best in Show judging. AMERICAN WATER SPANIEL STANDARD SCHNAUZERS ENTLEBUCHER MOUNTAIN DOG BOYKIN SPANIEL AMERICAN STAFFORDSHIRE FINNISH LAPPHUND ENGLISH SPRINGER SPANIEL IRISH TERRIERS ICELANDIC SHEEPDOGS FIELD SPANIEL KERRY BLUE TERRIER NORWEGIAN BUHUND LAGOTTO ROMAGNOLO MINI BULL TERRIER (Ground/Table) POLISH LOWLAND SHEEPDOG NS DUCK TOLLING RETRIEVER SOFT COATED WHEATEN TERRIER SPANISH WATER DOG WELSH SPRINGER SPANIEL STAFFORDSHIRE BULL TERRIER MUDI (Misc.) GRAND BASSET GRIFFON VENDEEN FINNISH SPITZ NORRBOTTENSPETS (Misc.) WHIPPET (Ground/Table) BREEDS THAT MUST BE JUDGED ON RAMP Applies to all conformation competition associated with AKC conformation dog shows or at any event at which an AKC conformation title may be earned. -

Sporting Group Study Guide Naturally Active and Alert, Sporting Dogs Make Likeable, Well-Rounded Companions

Sporting Group Study Guide Naturally active and alert, Sporting dogs make likeable, well-rounded companions. Remarkable for their instincts in water and woods, many of these breeds actively continue to participate in hunting and other field activities. Potential owners of Sporting dogs need to realize that most require regular, invigorating exercise. The breeds of the AKC Sporting Group were all developed to assist hunters of feathered game. These “sporting dogs” (also referred to as gundogs or bird dogs) are subdivided by function—that is, how they hunt. They are spaniels, pointers, setters, retrievers, and the European utility breeds. Of these, spaniels are generally considered the oldest. Early authorities divided the spaniels not by breed but by type: either water spaniels or land spaniels. The land spaniels came to be subdivided by size. The larger types were the “springing spaniel” and the “field spaniel,” and the smaller, which specialized on flushing woodcock, was known as a “cocking spaniel.” ~~How many breeds are in this group? 31~~ 1. American Water Spaniel a. Country of origin: USA (lake country of the upper Midwest) b. Original purpose: retrieve from skiff or canoes and work ground c. Other Names: N/A d. Very Brief History: European immigrants who settled near the great lakes depended on the region’s plentiful waterfowl for sustenance. The Irish Water Spaniel, the Curly-Coated Retriever, and the now extinct English Water Spaniel have been mentioned in histories as possible component breeds. e. Coat color/type: solid liver, brown or dark chocolate. A little white on toes and chest is permissible. -

Premium Lists Friday, September 14, 2018

Premium Lists Friday, September 14, 2018 Friday & Saturday, September 14 & 15, 2018 Saturday & Sunday September 15 & 16, 2018 Premium Lists Friday, September 14, 2018 • Show Hours 7:00 am to 8:00 pm Gateway Sporting Dog Association Event 2018569402 Page 17 Licensed by the American Kennel Club Classes Limited To Sporting Breeds Only Designated Specialty & Sweepstakes: Welsh Springer Spaniel Club of America, Inc Event 2018167013 Page 20 Supported Entry & Sweepstakes: Field Spaniel Society of America Event 2018390019 Page 19 Supported Entry: Wirehaired Vizsla Club of America Gateway Hound Club Event 2018708802 Page 23 Licensed by the American Kennel Club No Classes for Portuguese Podengo Pequenos Classes Limited To Hound Breeds Only • AKC National Owner‐Handled Series Hound Group Sweepstakes & Veteran Sweepstakes Designated Specialty & Sweepstakes: Greyhound Club of America Event 2018192514 Page 25 Supported Entry: Ibizan Hound Club of the United States Gateway Terrier Association Event 2018619105 Page 27 Licensed by the American Kennel Club Classes Limited To Terrier Breeds Only INDOORS • Unbenched • Show Hours 7:00 am to 6:00 pm Central Time Dalmatian Club of Greater St Louis Licensed by the American Kennel Club Friday, September 14, 2018 Page 29 Saturday, September 15, 2018 Page 29 Specialty Show with Junior Showmanship Concurrent w/Three Rivers Kennel Club of Missouri Sweepstakes & Vet. Sweepstakes Specialty Show w/Junior Showmanship Event 2018115705 Event 2018115706 (Entry Limit 100) AKC National Owner‐Handled Series AKC National Owner‐Handled -

Dog Breeds in Groups

Dog Facts: Dog Breeds & Groups Terrier Group Hound Group A breed is a relatively homogeneous group of animals People familiar with this Most hounds share within a species, developed and maintained by man. All Group invariably comment the common ancestral dogs, impure as well as pure-bred, and several wild cousins on the distinctive terrier trait of being used for such as wolves and foxes, are one family. Each breed was personality. These are feisty, en- hunting. Some use created by man, using selective breeding to get desired ergetic dogs whose sizes range acute scenting powers to follow qualities. The result is an almost unbelievable diversity of from fairly small, as in the Nor- a trail. Others demonstrate a phe- purebred dogs which will, when bred to others of their breed folk, Cairn or West Highland nomenal gift of stamina as they produce their own kind. Through the ages, man designed White Terrier, to the grand Aire- relentlessly run down quarry. dogs that could hunt, guard, or herd according to his needs. dale Terrier. Terriers typically Beyond this, however, generali- The following is the listing of the 7 American Kennel have little tolerance for other zations about hounds are hard Club Groups in which similar breeds are organized. There animals, including other dogs. to come by, since the Group en- are other dog registries, such as the United Kennel Club Their ancestors were bred to compasses quite a diverse lot. (known as the UKC) that lists these and many other breeds hunt and kill vermin. Many con- There are Pharaoh Hounds, Nor- of dogs not recognized by the AKC at present. -

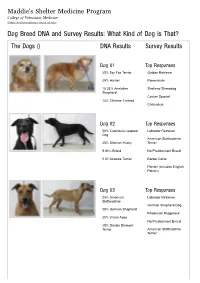

Dog Breed DNA and Survey Results: What Kind of Dog Is That? the Dogs () DNA Results Survey Results

Maddie's Shelter Medicine Program College of Veterinary Medicine (https://sheltermedicine.vetmed.ufl.edu) Dog Breed DNA and Survey Results: What Kind of Dog is That? The Dogs () DNA Results Survey Results Dog 01 Top Responses 25% Toy Fox Terrier Golden Retriever 25% Harrier Pomeranian 15.33% Anatolian Shetland Sheepdog Shepherd Cocker Spaniel 14% Chinese Crested Chihuahua Dog 02 Top Responses 50% Catahoula Leopard Labrador Retriever Dog American Staffordshire 25% Siberian Husky Terrier 9.94% Briard No Predominant Breed 5.07 Airedale Terrier Border Collie Pointer (includes English Pointer) Dog 03 Top Responses 25% American Labrador Retriever Staffordshire German Shepherd Dog 25% German Shepherd Rhodesian Ridgeback 25% Lhasa Apso No Predominant Breed 25% Dandie Dinmont Terrier American Staffordshire Terrier Dog 04 Top Responses 25% Border Collie Wheaten Terrier, Soft Coated 25% Tibetan Spaniel Bearded Collie 12.02% Catahoula Leopard Dog Briard 9.28% Shiba Inu Cairn Terrier Tibetan Terrier Dog 05 Top Responses 25% Miniature Pinscher Australian Cattle Dog 25% Great Pyrenees German Shorthaired Pointer 10.79% Afghan Hound Pointer (includes English 10.09% Nova Scotia Duck Pointer) Tolling Retriever Border Collie No Predominant Breed Dog 06 Top Responses 50% American Foxhound Beagle 50% Beagle Foxhound (including American, English, Treeing Walker Coonhound) Harrier Black and Tan Coonhound Pointer (includes English Pointer) Dog 07 Top Responses 25% Irish Water Spaniel Labrador Retriever 25% Siberian Husky American Staffordshire Terrier 25% Boston -

2017 Horrible Hundred Report

The Horrible Hundred 2017 A sampling of problem puppy mills and puppy dealers in the United States May 2017 For the fifth straight year, The Humane Society of the United States is reporting on problem puppy mills, including some dealers (re-sellers) and transporters. The Horrible Hundred 2017 report is a list of known, problematic puppy breeding and/or puppy brokering facilities. It is not a list of all puppy mills, nor is it a list of the worst puppy mills in the country. The HSUS provides this update annually, not as a comprehensive inventory, but as an effort to inform the public about common, recurring problems at puppy mills. The information in this report demonstrates the scope of the puppy mill problem in America today, with specific examples of the types of violations that researchers have found at such facilities, for the purposes of warning consumers about the inhumane conditions that so many puppy buyers inadvertently support. The year 2017 has been a difficult one for puppy mill watchdogs. Efforts to get updated information from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) on federally-inspected puppy mills were severely crippled due to the USDA’s removal on Feb. 3, 2017 of all animal welfare inspection reports and most enforcement records from the USDA website. As of April 20, 2017, the USDA had restored some Puppies at the facility of Alvin Nolt in Thorpe, Wisconsin, were found on unsafe wire flooring, a repeat violation at the facility. Wire flooring animal welfare records on research facilities and is especially dangerous for puppies because their legs can become other types of dealers, but almost no records on entrapped in the gaps, leaving them unable to reach food, water or pet breeding operations were restored. -

Baskerville Ultra Muzzle Breed Guide. Sizes Are Available in 1 - 6 and Are for Typical Adult Dogs & Bitches

Baskerville Ultra Muzzle Breed Guide. Sizes are available in 1 - 6 and are for typical adult dogs & bitches. Juveniles may need a size smaller. ‡ = not recommended. The number next to the breeds below is the recommended size. Boston Terrier ‡ Bulldog ‡ King Charles Spaniel ‡ Lhasa Apso ‡ Pekingese ‡ Pug ‡ St Bernard ‡ Shih Tzu ‡ Afghan Hound 5 Airedale 5 Alaskan Malamute 5 American Cocker 2 American Staffordshire 6 Australian Cattle Dog 3 Australian Shepherd 3 Basenji 2 Basset Hound 5 Beagle 3 Bearded Collie 3 Bedlington Terrier 2 Belgian Shepherd 5 Bernese MD 5 Bichon Frisé 1 Border Collie 3 Border Terrier 2 Borzoi 5 Bouvier 6 Boxer 6 Briard 5 Brittany Spaniel 5 Buhund 2 Bull Mastiff 6 Bull Terrier 5 Cairn Terrier 2 Cavalier Spaniel 2 Chow Chow 5 Chesapeake Bay Retriever 5 Cocker (English) 3 Corgi 3 Dachshund Miniature 1 Dachshund Standard 1 Dalmatian 4 Dobermann 5 Elkhound 4 English Setter 5 Flat Coated Retriever 5 Foxhound 5 Fox Terrier 2 German Shepherd 5 Golden Retriever 5 Gordon Setter 5 Great Dane 6 Greyhound 5 Hungarian Vizsla 3 Irish Setter 5 Irish Water Spaniel 3 Irish Wolfhound 6 Jack Russell 2 Japanese Akita 6 Keeshond 3 Kerry Blue Terrier 4 Labrador Retriever 5 Lakeland Terrier 2 Lurcher 5 Maltese Terrier 1 Maremma Sheepdog 5 Mastiff 6 Munsterlander 5 Newfoundland 6 Norfolk/Norwich Terrier 1 Old English Sheepdog 5 Papillon N/A Pharaoh Hound 5 Pit Bull 6 Pointers 4 Poodle Toy 1 Poodle Standard 3 Pyrenean MD 6 Ridgeback 5 Rottweiler 6 Rough Collie 3 Saluki 3 Samoyed 4 Schnauzer Miniature 2 Schnauzer 3 Schnauzer Giant 6 Scottish Terrier 3 Sheltie 2 Shiba Inu 2 Siberian Husky 5 Soft Coated Wheaten 4 Springer Spaniel 4 Staff Bull Terrier 6 Weimaraner 5 Welsh Terrier 3 West Highland White 2 Whippet 2 Yorkshire Terrier 1 . -

Welsh Springer Spaniel Club of America National Specialty AKC Conformation Event #: 2012167007 AKC Obedience Event #: 2012167011, AKC Rally Event #: 2012167015

Welsh Springer Spaniel Club of America National Specialty AKC Conformation Event #: 2012167007 AKC Obedience Event #: 2012167011, AKC Rally Event #: 2012167015 WEDNESDAY, May 2, 2012 THURSDAY, May 3, 2012 Olympia Resort & Conference Center 1350 Royale Mile Road Oconomowoc, WI 53066 Phone: 1-800-558-9573 ENTRIES CLOSE 6:00 PM on Wednesday, April 11, 2012 after which time entries cannot be accepted, canceled, or changed except as provided for in Chapter 14, Section 6 of the Dog Show Rules. Unbenched-Indoor / Show Hours 7:00AM to 6:00 PM (Local Time) Dogs need to be present only at scheduled time of judging. Dogs not required for further judging will be excused as soon as judged. Show site will be available to exhibitors on Monday, April 30, 2012 at 6PM for set up. MAKE CHECKS PAYABLE TO Heartland WSSC AND MAIL ALL ENTRIES WITH FEES TO: *Joan Kaml 4480 North 144th Street Brookfield, WI 53005 262-781-8072 [email protected] *PLEASE NOTE THAT SIGNATURE RECEIPTS MUST BE WAIVED. American Kennel Club Certification Permission has been granted by the American Kennel Club for the holding of these events under the American Kennel Club rules and regulations. James P. Crowley, Secretary Brookfield, WI 53005 SHOW SECRETARY Joan Kaml 144th Street 4480 North Welsh Springer Spaniel Club of America, Inc. Officers & Board Catalog Advertising Form for President: Cindy Ford WELSH SPRINGER SPANIELS Vice President: Sandy Holmes Recording Secretary: Wendy Jordan Catalog Advertising – Specialty catalogs are important references. Corresponding Secretary: Carla Vooris Treasurer: Mary Johnson Make this year’s catalog special and take out an ad and showcase Directors: Kit Goodrich, Lisa Hubler, Franna Pitt, your dogs or wish everyone good luck.