Cellular Phone Cloning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scamming Grandma: Financial Fraud and the Impact on Households Samantha Nielsen

The Institute for Behavioral and Household Finance White Paper Series Scamming Grandma: Financial Fraud and the Impact on Households Samantha Nielsen Cornell University © 2019 All rights reserved. White Paper No. 7-2019 May 2019 The Institute for Behavioral and Household Finance Cornell University ꞏ The Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management ꞏ Warren Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853 ꞏ E-mail: [email protected] ꞏ http://ibhf.cornell.edu Institute of Behavioral and Household Finance – White Paper Series White Paper: 07-2019 Overview more by scammers, are more educated on where to file a complaint, are more interested in Many Americans have experienced or know of a combatting fraud, or a combination of these or person who has fallen victim to a financial scam, other factors. and as social media platforms, online databases, and internet services expand, reports of these Figure 1: Historical Household Financial Fraud Reports scams become more widespread. While word-of- 1,800,000 mouth stories and news vehicles raise awareness, 1,600,000 there is limited existing research analyzing the 1,400,000 financial impact of these scams on households. 1,200,000 1,000,000 Figure 1 illustrates the total number of annual 800,000 600,000 fraud reports in the United States. From 2007 to 400,000 2016, an increase of 157% was seen in the 200,000 number of reported financial scams. More 0 recently, in 2018, there were 1,427,563 fraud reports, which is up 25% from 2017. The amount Source: Consumer Sentinel Network, 2007-2016 of 2018 reports with a monetary loss increased 48% to 358,755 from the year prior, and the Figure 2: Fraud Reports by Age Group median monetary loss for all fraud reports was down $375 in 2018, 13% less than the year prior.1 140,000 120,000 100,000 When we look at fraud reports by age group, a 80,000 significant increase in frauds reported by older 60,000 40,000 age cohorts is identified. -

North East Multi-Regional Training Instructors Library

North East Multi-Regional Training Instructors Library 355 Smoke Tree Business Park j North Aurora, IL 60542-1723 (630) 896-8860, x 108 j Fax (630) 896-4422 j WWW.NEMRT.COM j [email protected] The North East Multi-Regional Training Instructors Library In-Service Training Tape collection are available for loan to sworn law enforcement agencies in Illinois. Out-of-state law enforcement agencies may contact the Instructors Library about the possibility of arranging a loan. How to Borrow North East Multi-Regional Training In-Service Training Tapes How to Borrow Tapes: Call, write, or Fax NEMRT's librarian (that's Sarah Cole). Calling is probably the most effective way to contact her, because you can get immediate feedback on what tapes are available. In order to insure that borrowers are authorized through their law enforcement agency to borrow videos, please submit the initial lending request on agency letterhead (not a fax cover sheet or internal memo form). Also provide the name of the department’s training officer. If a requested tape is in the library at the time of the request, it will be sent to the borrower’s agency immediately. If the tape is not in, the borrower's name will be put on the tape's waiting list, and it will be sent as soon as possible. The due date--the date by which the tape must be back at NEMRT--is indicated on the loan receipt included with each loan. Since a lot of the tapes have long waiting lists, prompt return is appreciated not only by the Instructors' Library, but the other departments using the video collection. -

Sok: Fraud in Telephony Networks

SoK: Fraud in Telephony Networks Merve Sahin∗y, Aurelien´ Francillon∗, Payas Guptaz, Mustaque Ahamadx ∗Eurecom, Sophia Antipolis, France fmerve.sahin, [email protected] yMonaco Digital Security Agency zPindrop, Atlanta, USA [email protected] xGeorgia Institute of Technology, USA [email protected] Abstract—Telephone networks first appeared more than a future research, increase cooperation between researchers hundred years ago, long before transistors were invented. They, and industry and finally help in fighting such fraud. therefore, form the oldest large scale network that has grown Although, we focus on telephony fraud, our work has to touch over 7 billion people. Telephony is now merging broader implications. For example, a recent work shows many complex technologies and because numerous services how telephony fraud can negatively impact secure creation enabled by these technologies can be monetized, telephony of online accounts [1]. Also, online account takeovers by attracts a lot of fraud. In 2015, a telecom fraud association making a phone call to a call center agent have been reported study estimated that the loss of revenue due to global telecom in the past [2], [3]. Telephony is considered as a trusted fraud was worth 38 billion US dollars per year. Because of the medium, but it is not always. A better understanding of convergence of telephony with the Internet, fraud in telephony telephony vulnerabilities and fraud will therefore help us networks can also have a negative impact on security of online understand potential Internet attacks as well. services. However, there is little academic work on this topic, in part because of the complexity of such networks and their 1.1. -

Hang up on Cross-Border Phone Fraud

Hang Up on Cross-Border Phone Fraud It’s like clockwork. You sit down to dinner and the phone rings. You answer it. The caller is trying to sell you something or tell you that you’ve won a fabulous prize. In fact, you may have been targeted by fraudulent telemarketers calling across the border from “boiler rooms” in the U.S. and Canada... ross-border telemarketing C fraud is a serious problem — and it appears to be growing. U.S. and Cana- dian consumers lose billions of dollars a year to telemarketers who pitch bogus products, services and investments. The most common cross-border telemarketing frauds involve: ● phony prize promotions ● foreign lottery schemes ● advance-fee loan rip-offs ● travel offer scams ● unnecessary credit card loss “protection” It’s no wonder that con artists often target citizens of other countries. Some con artists believe they won’t get caught if they target citizens in another country. They assume that their own country’s law enforcement officials aren’t interested in building a case when the victims are in another country. They also believe that officials in the victims’ country won’t have the authority to investigate deceitful calls from outside their borders. But now partnerships among law enforce- ment agencies in the U.S. and Canada are making it tougher for cross-border scam artists to ply their deceitful trade. The organizations cooperate across borders — sharing information, investigators and other resources. All the partners gather consumer complaint information and contribute to the 1 legwork involved in building a case, in- cluding surveillance and interviewing victims. -

Identity Theft and Telemarketing Fraud

If I get the caller ID information it should What can I do to protect myself from be able to track them, right? phone fraud? Wrong. Unfortunately, the technology is readily Identity Theft and available for criminals to mask the numbers they Telemarketing Fraud Register for the National DNC are calling from, thwarting enforcement efforts to Program by calling toll free: 1-888-382-1222 identify them. Remember, the good guys have to go through every LEGAL means to catch these Your personal information is valuable. You can limit the number of legitimate telemar- criminals, the crooks go through every means Protect it! Guard your: keting calls you receive at your residence by reg- available to evade detection. That’s why it is im- istering your home phone number on the LPSC portant that you understand that educating yourself, Social Security number DNC Program and/or National DNC Program. and your friends and family, to the dangers of iden- Putting your number on these programs will stop tify theft is your best protection against this type of Bank and credit card numbers most normal telemarketing calls - but not all. You crime. Do Not Call was never designed to stop Driver's license number still may get calls from businesses with which you fraud, but we can help you get your complaint to normally do business, and a few other possible the appropriate authority. exemptions, but calls from sales people from un- Some criminals lie on the telephone to familiar businesses may be the sign of a scam. Be- What should I do if I suspect fraud? get your personal information. -

Employee Fraud Detection Under Real World Conditions

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2010 Employee fraud detection under real world conditions Luell, J Abstract: Employee fraud in financial institutions is a considerable monetary and reputational risk. Stud- ies state that this type of fraud is typically detected by a tip, in the worst case from affected customers, which is fatal in terms of reputation. Consequently, there is a high motivation to improve analytic de- tection. We analyze the problem of client advisor fraud in a major financial institution and find that it differs substantially from other types of fraud. However, internal fraud at the employee level receives little attention in research. In this thesis, we provide an overview of fraud detection research with the focus on implicit assumptions and applicability. We propose a decision framework to find adequate fraud detection approaches for real world problems based on a number of defined characteristics. By applying the decision framework to the problem setting we met at Alphafin the chosen approach is motivated. The proposed system consists of a detection component and a visualization component. A number of imple- mentations for the detection component with a focus on tempo-relational pattern matching is discussed. The visualization component, which was converted to productive software at Alphafin in the course of the collaboration, is introduced. On the basis of three case studies we demonstrate the potential of the proposed system and discuss findings and possible extensions for further refinements. Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-44863 Dissertation Originally published at: Luell, J. -

Protect Your Loved Ones: the 411 on Senior Scams and Fraud by Nan Hayes for Caring Transitions

Protect Your Loved Ones: The 411 on Senior Scams and Fraud By Nan Hayes for Caring Transitions When writing this newsletter, I received an email from my cell phone provider, including its name and brand images, informing me I must immediately pay hundreds of dollars in late penalties or lose my service. The message looked legitimate, even though I knew it couldn’t be true. Upon taking a closer look at the sender’s address, I determined it was a scam. But would my 86-year old father have known the difference? If you’re 40 or older, chances are you are part of the “Sandwich Generation,” a term used to describe the growing number of adults who are simultaneously caring for aging parents and raising children, while managing demanding careers and tending to household duties. Much of your time, energy and attention is focused on family as you make sure everyone is safe, secure and living comfortably. At times, your responsibilities may be overwhelming and you don’t know where to seek relief. The good news is “parent care” is quickly becoming the norm and you are in good company. In today’s fast-paced, multimedia environment, we have access to countless online resources that provide information and advice with a few clicks of a button. The internet has become a haven for caregivers as they seek advice, support and a sense of community with fellow caregivers; however, the unfortunate reality is that the internet has also become a haven for many scam operators who prey on the elderly by using unfamiliar and unexpected ploys. -

Detecting Fraud in Cellular Telephone Networks

Islamic University of Gaza Deanery of Graduate Studies Faculty of Commerce Department of Business Administration Detecting Fraud in Cellular Telephone Networks "JAWWAL" Case Study By Hiyam Ali El Tawashi Supervised By Prof. Yousef Hussein Ashour “A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree in "MBA" August, 2010 ﺑﺴﻢ ﺍﷲ ﺍﻟﺮﲪﻦ ﺍﻟﺮﺣﻴﻢ (ﻭﺇِﻥ ﻳﺮِﻳﺪﻭﺍْ ﺃَﻥ ﻳﺨْﺪﻋﻮﻙَ ﻓَﺈِﻥ ﺣﺴﺒﻚ ﺍﻟﻠّﻪ ﻫﻮ ﺍﻟﱠﺬﻱ ﺃَﻳﺪﻙَ ﺑِﻨﺼﺮِﻩ ﻭﺑِﺎﻟْﻤﺆﻣﻨﲔ ) [ﺍﻷﻨﻔﺎل: 62] III Detecting Fraud in Cellular Telephone Networks "JAWWAL" Case Study ABSTRACT Telecommunication fraud is a problem that has grown dramatically over the past ten years. Fraud become a serious global issue for mobile network service providers, it has undoubtedly become a significant source of revenue losses and bad debts to telecommunication industry, and with the expected continuing growth in revenue it can be expected that fraud will increase proportionally. The research project therefore, focused on how Jawwal Company managing and detecting the fraud, in order to modify the current tools for more effective fraud prevention and detection, for this reason the researcher undertook a set of actions that are reported as follow: First step it was necessary to understand the problem of telecom fraud, then to know what makes people perpetrate the fraud, and which are the most prevalent fraud types that are occurring, clarifying which is the likely products and services to be attacked, what source of information to facilitate the fraud, how fraudsters perpetrate the fraud finally explaining the fraud detection and prevention procedures. Then apply the study on Jawwal Company as study case, by distributing 200 questionnaires to targeted sections, and analyzing the result which shows that the current fraud management at Jawwal Company is not efficient and needs to be modified. -

Low-Cost So Id the Schematic for Ele Apture and Pawing Rogram That's Telco in a Box Right for You! Test Your Telephone Devices with This Phone-Line Simulator

SEPTEMBER 1995 EleconicsCombined with Electronics® e help you Low-Cost So Id the schematic For Ele apture and pawing rogram that's Telco In A Box right for you! Test your telephone devices with this phone-line simulator Build Your Own SIMM Memory Modules Recycle your old memory and save a bundle! Over/Under Voltage Monitor Protect your sensitive electronic equipment from sags and surges $3.50 U.S. 0 9 > Carbon-Monoxide Detector $3.95 CAN. This easy-to-build unit 091 28 48783 could save your life! www.americanradiohistory.com A cr as courser in why you can always count on -- -- Fluke meters. := Professionals know Fluke never lets you down. Every day, you're asked to rise to new challenges. You need a test tool as tough as your job. True story: a tech working atop a 170 -foot tower accidentally knocks his Fluke 23 meter and an industrial -grade screwdriver over the edge. Straight down they fall, crashing to the asphalt below. He goes down. His screwdriver's handle is shattered. Expecting the worst, he gingerly picks up his Fluke meter and smiles. All that's broken is a fuse. He snaps in another, goes right back up and continues testing with the same Fluke 23. No harm to the meter - or the pocketbook. Unbelievable? Not when you consider every rotary knob, keypad, and switch on every Fluke meter must pass strict testing for drops, intense heat or cold, electrical overloads, and years of harsh wear and tear. What's more, Fluke meters are built in an ISO 9001 certified factory. -

876-Scam: Jamaican Phone Fraud Targeting Seniors: Hearing

S. HRG. 113–806 876–SCAM: JAMAICAN PHONE FRAUD TARGETING SENIORS HEARING BEFORE THE SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON AGING UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION WASHINGTON, DC WEDNESDAY, MARCH 13, 2013 Serial No. 113–2 Printed for the use of the Special Committee on Aging ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 81–474 PDF WASHINGTON : 2016 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Sep 11 2014 13:08 Jun 23, 2016 Jkt 097434 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\DOCS\81474.TXT SHAWN DeShaun on LAP51NQ082 with DISTILLER SPECIAL COMMITTEE ON AGING BILL NELSON, Florida, Chairman RON WYDEN, Oregon SUSAN M. COLLINS, Maine ROBERT P. CASEY JR, Pennsylvania BOB CORKER, Tennessee CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri ORRIN HATCH, Utah SHELDON WHITEHOUSE, Rhode Island MARK KIRK, Illinois KIRSTEN E. GILLIBRAND, New York DEAN HELLER, Nevada JOE MANCHIN III, West Virginia JEFF FLAKE, Arizona RICHARD BLUMENTHAL, Connecticut KELLY AYOTTE, New Hampshire TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin TIM SCOTT, South Carolina JOE DONNELLY Indiana TED CRUZ, Texas ELIZABETH WARREN, Massachusetts KIM LIPSKY, Majority Staff Director PRISCILLA HANLEY, Minority Staff Director (II) VerDate Sep 11 2014 13:08 Jun 23, 2016 Jkt 097434 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 C:\DOCS\81474.TXT SHAWN DeShaun on LAP51NQ082 with DISTILLER CONTENTS Page Opening Statement of Ranking Member Susan M. Collins ................................. 1 Statement of Chairman Bill Nelson ...................................................................... -

Fighting Fraud: Senate Aging Committee Identifies Top 10 Scams Targeting Our Nation’S Seniors

United States Senate Special Committee on Aging Fighting Fraud: Senate Aging Committee Identifies Top 10 Scams Targeting Our Nation’s Seniors Senator Susan M. Collins (R-ME), Chairman Senator Robert P. Casey, Jr. (D-PA), Ranking Member Tips from the United States Senate Special Committee on Aging for Avoiding Scams • Con artists force you to make decisions fast and may threaten you. • Con artists disguise their real numbers, using fake caller IDs. • Con artists sometimes pretend to be the government (e.g. IRS). • Con artists try to get you to provide them personal information like your Social Security number or account numbers. • Before giving out your credit card number or money, please ask a friend or family member about it. • Beware of offers of free travel! If you receive a suspicious call, hang up and please call the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging’s Fraud Hotline at 1-855-303-9470 Note: This document has been printed for information purposes. It does not represent either findings or recommendations formally adopted by the Committee. Protecting Older Americans Against Fraud Unitedi d SSStates Senate SiSpeciall CommitteeCi on Aging i Table of Contents Dear Friends ...........................................................................................................................................3 Top 10 Most-Reported Scams ................................................................................................................4 Abbreviations ..........................................................................................................................................6 -

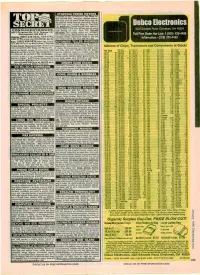

Debco Electronics

epode on 8 60 'INUTE : ow certa n de- vices can slow down - even slop watthour meters - while loads draw lull power! Device simply plugs Into one outlet and normal loads Into other outlets. Also de- scribes meter creep, overload droop. etc. Plans $29. Debco Electronics 1.9.-MAHUALLExlernal magnetic ways (applied to the meter Itself) to slow down and stop watthour meters 4025 Edwards Roadl, Cincinnati, OH 45209 CONSUMERTRONICS while drawing full loads. Plans. $19. !MAR 2011 Crescent Dr., P.O. Drawer 537 METERS: How watthour meters work, calibration, 1 423 Alamogordo, NM 88310 error modes (many), ANSI Standards, etc. Demand and Toll Free Order Hot Line (800) -4499 results to slow and Voice: (505) 434.0234, 434.1778, Polyphase Meters. Experimental Information - (513) 531 -4499 439-1776 (orders only) 8AM -6PM MST. Mon -Sat star meters It others. $19. An 2, $38. All 3, 559. Fax: 505)1 434-0234 (orders only; a you get AUTOMATIC TELLER MACHINES voice. e1 any time) 24 -hour, 7 days/wk enter 'e11 t- ATM crimes, abuses, vulnerabilities and defeats ex- Fran 2arh.. up orL (relates directly to your posed' 100+ methods detailed, Include: Physical, Reg. Millions O'l Chips, Transistors and Components in Stock! order or prospective order Tue.. and Thurs. only. E, cipher, PIN compromise, card countedeitng, mag- .008 80 Add S5 total SM (US, Canada). All items In stock VISA, netic stripe, false front, TEMPEST, Van Eck, tapping. 74LSxx 74LS194 - .E9 74HC10 - - - .30 .79 .89 LF347 vibration, pulse, high 14LS195- 69 74HC11 .34 '009 .73 4531 .99 1.61348 .65 MCard OK.