Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Youth Culture and Nightlife in Bristol

Youth culture and nightlife in Bristol A report by: Meg Aubrey Paul Chatterton Robert Hollands Centre for Urban and Regional Development Studies and Department of Sociology and Social Policy University of Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU, UK In 1982 there were pubs and a smattering of (God help us) cocktail bars. The middle-aged middle classes drank in wine bars. By 1992 there were theme pubs and theme bars, many of them dumping their old traditional names in favour of ‘humorous’ names like The Slug and Lettuce, The Spaceman and Chips or the Pestilence and Sausages (actually we’ve made the last two up). In 2001 we have a fair few pubs left, but the big news is bars, bright, shiny chic places which are designed to appeal to women rather more than blokes with swelling guts. In 1982 they shut in the afternoons and at 11pm weekdays and 10.30pm Sundays. In 2001 most drinking places open all day and many late into the night as well. In 1982 we had Whiteladies Road and in 2001 we have The Strip (Eugene Byrne, Venue Magazine July, 2001 p23). Bristol has suddenly become this cosmopolitan Paris of the South West. That is the aspiration of the council anyhow. For years it was a very boring provincial city to live in and that’s why the music that’s come out of it is so exciting. Cos it’s the product of people doing it for themselves. That’s a real punk-rock ethic. (Ian, music goer, Bristol). Contents Contents 2 List of Tables 5 Introduction 6 Chapter 1. -

July Justice, Our Church Lias Become a Donna Red Wing Ofthe Gill Foun 1973, the Gay Liberation Front Stronger Faith-Centered Body

Annual meeting mLOCAL AND STATE looks back at 2002 Empty Cioset unveils Chuck Bowen gives GAGV's vision for She future online edition website The Empty Ooset will go online just Chuck Bowen sketched his vision By Susan Jordan in time for Pride. The online ver for the future of the Alliance, de~ Approximateiy 100 people were sion of the paper can be found at scribing the areas to be covered by present at the Gay Alliance's an [email protected]. th« structural reo*-ganization: opera nual meeting at the Clarion River Advertising will eventually be sold tions/management, development, side Hotel on June 8 — coinci forthe online EC, and news articles community relations (programming) dentaliy, just about the same num^ can now l>e up<teted on a weekly or and communications. He noted that ber tfiat were present at the very daily basis. The GAGV website has the passage of SONDA will gjve the first meeting in 1973 of the group also been completely re-designed: that was to become the GAGV. Gay Alliance the task of educating visit www.gayalUance.org. Board member Evelyn Baiiey, k>cal businesses about how to be in Ribv* Ron HelvTts leaves who hmnds the 30th anniversary compliance with the state's new anti Ofsen Ai-ms ^fCC discrimination protections for Igbt celebration commit£e«, gave a On June 22, Rev. Ron Helms ended brief history ofthe Alliance, start people. SPECIAL PRIOE/HISTOilY ISSUE: Above: Our first cotor photo his seven-year ministry at Open ing with the events of Oct 3. -

Download Someday at at the Lo Pub

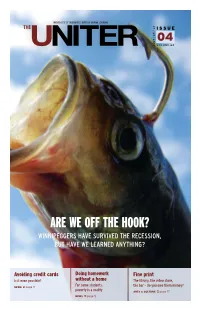

/ 25 24 2010 / 03 Why you shouldn’t run for mayor COMMMENTS page 8 orthodontic art The tormented world of Kris Row ARTS & CULTURE page 15 Who’s Watching out for you doWntoWn? NEWS page 3 02 The UniTer March 25, 2010 www.UniTer.ca Syvixay re-elected You know that lookinG for listings? Cover Image movie 8 Mile? CAMpUS & communiTy ListiNgS ANd ...and other results volunteer OpportuniTies page 7, “Tower of Babel” by Kris Row from this month’s UwSa These guys lived it MUSiC page 12, fiLM & LiT page 14, Galleries & museums page 15, from the exhibition Tormented Dentist, on general elections display at Medea Gallery until March 27 Theatre, dANCE & comedy page 15, See story on page 15 awardS ANd fiNANCiAL Aid page 18 campUS news page 7 arts & culture page 11 Photograph by Cindy Titus News UNITER STAFF ManaGinG eDitor Aaron Epp » [email protected] BUSiness ManaGer will Earth Hour 2010 make a difference? Please contact [email protected] PrODUcTiOn ManaGer M Melody Morrissette » [email protected] E lo Global effort dy cOPy anD styLe eDitor Mo Things you can do Chris Campbell [email protected] happens Saturday, rrissette for The envirOnMenT » Photo eDitor March 27 every Day Cindy Titus » [email protected] choose energy-efficient newS assiGnMenT eDitor appliances. Andrew McMonagle » [email protected] LaUra KUNzeLmaN Switch to energy-efficient light bulbs. newS PrODUcTiOn eDitor volunteer Karen Kornelsen » [email protected] Plug the electronics that don’t need to be on all the arts anD culture eDitor Earth Hour 2010 is a global effort time into a main power bar and Sam Hagenlocher » [email protected] led by the World Wildlife Fund to switch it off before you head to cOMMents eDitor get people to turn off non-essen- bed at night. -

Avoiding Credit Cards Fine Print

24 09 / / 04 2009 VOLUME 64 Avoiding credit cards Doing homework Fine print Is it even possible? without a home The library, the video store, For some students, the bar – do you owe them money? news page 3 poverty is a reality arts & culture page 17 news page 5 02 The UniTer September 24, 2009 www.UniTer.ca Go green! Code of conduct: LooKInG FoR LIstInGs? Cover Image campus & community listings and Mickelthwate can't volunteer opportunities page 4 "namakan Lake Minnow" Win prizes! music page 12 wait to wave his baton galleries, theatre, dance and comedy page 13 Photograph by campus news page 6 arts & culture page 11 Film page 13, literature page 15 Bill Beso news UNITER STAFF ManaGinG eDitor Vacant » [email protected] BUSiness ManaGer Manitoba rejects harmonized sales tax Maggi Robinson » [email protected] PrODUcTiOn ManaGer Province would lose money if GST and PST amalgamate, finance minister says Melody Morrissette » [email protected] cOPy anD styLe eDitor Chris Campbell » [email protected] eThaN CaBel Photo eDitor Mark Reimer [email protected] BeaT reporTer » newS assiGnMenT eDitor Andrew McMonagle » [email protected] The Manitoba government has de- newS PrODUcTiOn eDitor cided that tax harmonization – a Cameron MacLean » [email protected] federal proposal to amalgamate the GST and the PST – will take away arts anD culture eDitor provincial tax control and hurt Aaron Epp » [email protected] consumers along the way. cOMMents eDitor “We are no longer considering Andrew Tod » [email protected] the option of an HST,” said Rosann Listings cOOrDinator Wowchuk, Manitoba minister of J.P. -

LOV July 2009

THE SIX DAYS OF STONEWALL JULY/ AUGUST ISSUE 01 . 2009 living out vancouver lovmag.com PARTYTIME! PRIDE CELEBRATION ESSENTIALS PRIDEIN OUT OF THE CLOSET AND FASHIONONTO THE CATWALK VANCOUVER’S HOTTEST MALE MODELS ROCK THE RUNWAY THU JUL 30, 2009 CELEBRITIES 1022 Davie St. Doors 9 p.m. PrideShow Starts 11in p.m. Music by DJ Quest Performance by House of LaDouche $20 Advance at Little Sister’s Bookstore (1238 Davie St.) Priape (1148 Davie St.), and online at Celebritiesnightclub.com Fashion$25 At the door MODEL: NICOLAS D E HASS, MAKEUP: S TEVE N C ARTY, ARTY, S TYLIST: TYLIST: D EA NN A P ALKOWSKI. 3 4 in JULY/AUGUST ISSUE 01 . 2009 14 FEATURE Six Days in ’69: Revisiting the Stonewall Rebellion 26 PRIDE IN FASHION Boys’ Co, Michael Graft. Michael Co, Boys’ Gay culture’s impact Apparel: on mainstream fashion since Stonewall Steven Carty Carty Steven Grooming: 41 Deanna Palkowski Palkowski Deanna ylist: t S PRIDE HIGHLIGHTS The parties, performers and places to be Joe DallAntonia, Wayne Phillips Phillips Wayne DallAntonia, Joe Models: TJ Ngan Ngan TJ Photo: 6 TO OUR READERS 30 BODY & SOUL Team Vancouver Heads for Copenhagen 9 NEWS Is gay dating a new Olympic sport? 35 TRAVEL INSIDE STORY: What does the future hold for Ritchie Five Favourite Gay Getaways Dowrey after being attacked in a Vancouver gay bar? Local, national and international News Briefs 38 FOOD & DINING The Oasis Gets Fresh 23 STYLE 45 ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT Summer Fashion Must-Haves PopOuts: Gay pop culture News Briefs Rethinking the Beach Bungalow Vancouver Queer Film Festival Dump-to-Dream-Home DIY 50 JUL/AUG EVENT CALENDAR 5 living out vancouver EDITORIAL & CREATIVE TO OUR READERS DIRECTOR TJ NGAN elcome to the fi rst issue of LOV (Living Out Vancouver), Vancouver’s EDITOR fi rst gay men’s magazine. -

Garrett Wang Zoie Palmer Boy & Gurl ...And More! Scan to Read on Mobile Devices Back with Passion Pop

OCTOBER 2013 ® ISSUE 120 • FREE The Voice of Alberta’s LGBT Community Chi Chi LaRue Icon visits Edmonton MICHAEL Kris Holden-Ried URIE Hungry like the Wolf PLUS: Robert Englund Julian Richings Garrett Wang Zoie Palmer Boy & GurL ...and more! Scan to Read on Mobile Devices Back with Passion Pop Business Directory Community Map Events Calendar Tourist Information STARTING ON PAGE 55 Calgary • Alberta • Canada www.gaycalgary.com 2 GayCalgary Magazine #120, October 2013 www.gaycalgary.com Table of Contents OCTOBER 2013 ® 5 Up and Down Alberta Publisher: Steve Polyak Publisher’s Column Editor: Rob Diaz-Marino Sales: Steve Polyak Design & Layout: 8 The Skin I’m In now on DVD Rob Diaz-Marino, AraSteve Shimoon Polyak Broderick Fox’s film launches internationally on iTunes and Amazon Writers and Contributors 10 Cowboys, Armageddon, and the Truth ChrisMercedes Azzopardi, Allen, ChrisP.J. Bremner, Azzopardi, Dave Dallas Brousseau, Barnes, DaveJason Brousseau, Clevett, Andrew Sam Casselman, Collins, Mark Jason Dawson, Clevett, RobAndrew Diaz-Marino, Collins, Emily David-Elijah Collins, Rob Nahmod, Diaz-Marino, Janine 12 Catching Up with Michael Urie EvaJanine Trotta, Eva Trotta,Farley FooJack Foo,Fertig, Marisa Glen Hudson,Hanson, JoanEvan Kayne,Hilty, Evan Stephen Kayne, Lock, Stephen Lisa Lunney, Lock, Neil Steve McMullen, Polyak, Actor talks breaking from Ugly Betty, sexually mysterious new role and RomeoAllan Neuwirth, San Vicente Steve and Polyak, the LGBT Carey Community Rutherford, of 12 PAGE RomeoCalgary, San Vicente, Edmonton, Ed Sikov, -

Download Sole Brother At

/ 11 22 2010 / 03 Political parties at City Hall? Interview with the Vampires The debate continues Local death-pop duo gonna make you sweat NEWS page 3 ARTS & CULTURE page 13 02 The UniTer March 11, 2010 www.UniTer.ca Rock the vote "Boring doesn't just looking FoR listings? Cover Image CAmpUS & CommUNiTy ListiNgS ANd describe their political "Untitled 2" This year's UwSa general volunteer opportuniTies page 6, by Adrian Williams elections promise to be agenda, it is their mUSiC page 12, fiLm & LiT page 14, from the exhibition Let's Live Here, on display Galleries & museumS page 15, like no other political agenda." at Golden City Fine Art until March 27 Theatre, dANCE & ComEdy page 15, See story on page 15 awardS ANd fiNANCiAL Aid page 18 campUS news page 6 Comments page 10 PHotoGraph by Antoinette Dyksman News UNITER STAFF PeoPle Worth reading aBout ManaGinG eDitor Aaron epp » [email protected] BUSiness ManaGer rockin' the boat for a good cause Please contact [email protected] Cin local level and don't stop. Sooner PrODUcTiOn ManaGer D Manitoba should y Melody Morrissette » [email protected] t or later, somewhere down the it WoodstocK-iSMS be leader in green us Choice words from local activist line, someone will listen to you,” cOPy anD styLe eDitor Don Woodstock Woodstock said. Chris Campbell » [email protected] technology, local Shortly thereafter, he made a "The best way to keep a man Photo eDitor documentary, Your World and Mine, Cindy titus [email protected] activist says or woman silent is to give them highlighting the environmental ef- » a job. -

2011 Winnipeg Visitor's Guide

WINNIPEG2 011 VISItor’s GUIDE SMALLTOWNFRIENDLY BIGTOWNFUN YOUR ONE STOP SHOP FOR PLANNING YOUR TRIP TO WINNIPEG contents TOURISM WINNIPEG PARTNERS: Messages.....................................................................2-5 Manitoba Hotel Association 10.Winnipeg.Must.Sees..............................................6-7 204.942.0671 | www.manitobahotelassociation.ca Manitoba Restaurant and Foodservice Winnipeg.Information...............................................8-12 Association Things.To.Do............................................................. 13-71 204.783.9955 | www.mrfa.mb.ca 2011 Winnipeg Festivals & Events ............................................14-21 Tourisme Riel 2504.233.8343 | www.tourismeriel.com Entertainment Venues ......................................................... 22-24 Travel Manitoba Family Fun ............................................................................ 25-27 204.927.7800 | www.travelmanitoba.com Winnipeg Convention Centre Galleries ..............................................................................28-30 204.956.1720 | www.wcc.mb.ca Gaming..................................................................................31-32 BIZ Associations of Winnipeg: Museums / Historical ...........................................................33-40 Academy Road BIZ Nightlife ................................................................................41-44 204.947.0700 | www.academyroadbiz.com Corydon Avenue BIZ Of Interest ...........................................................................45-50 -

Erie Canal in Early Stereoviews

ST. - -. .. THE MAGAZINE OF 3-DIMENSIONAL IMAGING, PAST & PRESENT januaryFebruary Volume 22, Numb Publiid blllONAL TEREOSCOPIC 6SOCIATION, INC. First "Weather" Entries ntries have started arriving in our Weather assignment, but it Ecould hardly be called a bliz- zard. We know there are plenty of interesting weather related stereos out there, just waiting to be shared with Stereo World readers. Remem- ber, entries don't have to docu- ment storms that resulted in the declaration of a disaster area. Localized and benign conditions can result in some exceptional views of scenes that are accessible and often unnoticed by others. Just in time to offera little encour- agernent, S&D Enterprises of Zion, ZL, "Traffic lam in Cambridge" by Louis B. King of Somerville, MA. When trolley bus power has announced that they will send lines were damaged during a lanuary 12, 1996 snowstorm in Cambridge, Ma, Traffic was one box of their No. 3300 EMDE rerouted to this side street. The resulting snowy traffic jam was captured with a Kodak stereo slide binders to each stereogra- .................................................................................................................................................................stereo camera on Fujichrome Sensia. pher whose work appears on the Assignment 34) page, starting with damage, or things like close-ups of weather have had a visible, short the current Assignment. rain or dew covered leaves, ice term effect (this means other than encrusted flower buds, mud pud- formations created by centuries of Current Assignment: dles, flooded fields, dry cracked normal erosion) are what we have "Weather" earth, etc. Any image of "weather" in mind. On other words, "weath- This category is really wide itself in action (hypers of lightning er" here refers to conditions at open. -

Uniter-2011-10-06.Pdf

/06 06 2011 / 10 volume 66 History Mystery The Secrets of the Times Change(d) arts page 15 Save Gio's LGBT* club faces financial crunch news page 3 Reasons 4 why sports matter comments page 9 "Adding vocals to this band would be like throwing kitty litter into an already delicious milkshake." ARTS page 12 02 The UniTer OctobeR 6, 2011 www.UniTer.ca LookinG for LiStings? Cover Image CaMPUs & COMMUNItY LISTINGs aND PHOTO BY BRYAN SCOTT Green corridor construction Live music this week: VOLUNtEEr OPPORTUNItIEs PaGE 8 Waster, Socalled MUsIC PaGE 12 See more of Bryan's work at underway at the U of w FILM & LIt PaGE 14 www.winnipeglovehate.com GaLLErIEs & MUsEUMs PaGEs 14 & 15 Learn more about the CaMPUs NEWs page6 and more & tHEATRE, DaNCE & COMEDY PaGE 15 Times Change(d) High .COMMENTS page9 arts pages11,12&13 aWarDs & FINaNCIaL aID PaGE 18 Lonesome Club on page 15 People Worth Reading ABout UNITER STAFF Sharing fruit and promoting healthy living ManaGinG eDitor Sagan Morrow aims to foster community with south Osborne-based pilot project Aaron Epp » [email protected] BUSiness ManaGer Geoffrey Brown [email protected] Clara BUelow » volUNTeer PrODUcTiOn ManaGer Ayame Ulrich » [email protected] cOPy anD styLe eDitor It turns out you can share your fruit and eat it Britt Embry » [email protected] too. Photo eDitor Founded last year as a pilot project in south Dylan Hewlett » [email protected] Osborne, Fruit Share is an organization whose aim is to connect volunteers with homeown- newS assiGnMenT eDitor ers in order to salvage perfectly good fruit that Ethan Cabel » [email protected] would otherwise go to waste. -

Iii Fi/Stereo Review's

Iii fi/Stereo Review's $1.25 1966 TAPE RECOR ER ANNUAL EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT TAPE RECORDING How to Choose aRecorder -À Roundup of Video Recorders Tips on Tape EditIng Taping Stereo FM Microphones Picking the Best Tape How to Tape from Mscs PLUS: Directory of Stereo Tape Recorders, Accessories, Mikes Live Better Electronically With NEW! LAFAYETTE Eariterion 1000-- PROFESSIONAL 4-TRACK SELF-CONTAINED STEREO TAPE RECORDER 11 Ifi/Seo Wifl Review All things considered, I would rate the Criterion 1000 as one of the best under— $300 recorders i have tested. It sounds fine, looks even better, and sells for $199.50. HI FI Stereo Review May 1965 Records and plays 4-track stereo and mono tapes through its acoustically matched 6x4" hi-fi speakers. Three speeds, 71/2,3 /34 and 1% ips for up to 8 hours playing time. Six pushbutton tape motion controls. Genuine teakwood cabinet. With 2 dynamic mikes, cables and 7" take-up reel. Imported. 99-1501WX 199.50 LAFAYETTE DELUXE PORTABLE WIDELY ACCLAIMED LAFAYETTE LAFAYETTE DELUXE TAPE RECORDER Model RK-142 4-TRACK PORTABLE TAPE PUSHBUTTON 4-TRACK STEREO RECORDER Model RK-137A TAPE RECORDER Model RK-675 • Takes Reels Up To 7" Our finest portable. Records and plays Compact and lightweight, the RK-142 back 4-track stereo tapes. Six easy-to-use records and plays at 2 speeds, 7/12 and pushbuttons; 2 speeds, 7/12 and 3/34 ips; 3/34 ips, for up to 4 hours recording time. 2-speeds, 7/12 and 3/34 ips. -

GYPCANADA Gay Lesbian Canada Sept 2021

gypCanada 1 gypCanada gypCanada TM INFORMING THE LESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL & TRANSGENDER & ALLIES COMMUNITY SINCE 1973 ONLINE UPDATE September 2021 For reasons of copyright Canadian listings are published and hosted by, but no longer included in, Gayellow Pages online book: http://gayellowpages.com/online.htm Index page 67 The Index includes page number references to: Names, subject headings, subject cross references; Location references (e.g.: Bronx: see New York City Area) Publication names appear in italics Women’s Section page 3 Ethnic/Multicultural Section page 11 A work in progress. Corrections, additions and constructive criticism very welcome. All entries in the Ethnic/Multicultural Section also appear in the main section and, when appropriate, in the Women’s section. Main Canada listings begin page 13 To locate any particular city or subject please see the index page 65 YOU CAN SEARCH THIS PDF FILE WITH CONTROL-F September 1, 2021 2:49 pm September 2021 gypCanada Search this PDF file with control-F gypCanada September 2021 gypCanada 2 gypCanada gypCanada A not-for-profit enterprise (regardless of tax status) Updated September 2021 primarily operated by LGBTQ+ people. ✩A not-for-profit enterprise (regardless of tax status) not Editor & Publisher primarily operated by LGBTQ+ people z A business, wishing to be listed as wholly or partly Typesetting & Data Processing LGBTQ+ owned. FRANCES GREEN A gay-friendly business, not wishing to be listed as wholly email [email protected] or partly LGBTQ+ owned. Any entr y w hi ch does not have one of the abov e sy mbol s is beli ev ed to w elcom e gay/ lesbian/ bi sex ual/ transgender patronage, but no d ir ect r esp o nse had b e en r ece iv ed a t tim e o f p ub l ica tio n.