Oral History Interview with Willis Ware

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer Oral History Collection, 1969-1973, 1977

Computer Oral History Collection, 1969-1973, 1977 Interviewee: Morris Rubinoff Interviewer: Richard R. Mertz Date: May 17, 1971 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History MERTZ: Professor Rubinoff, would you care to describe your early training and background and influences. RUBINOFF: The early training is at the University of Toronto in mathematics and physics as an undergraduate, and then in physics as a graduate. The physics was tested in research projects during World War II, which was related to the proximity fuse. In fact, a strong interest in computational techniques, numerical methods was developed then, and also in switching devices because right after the War the proximity fuse techniques were used to make measurements of the angular motions of projectiles in flight. To do this it was necessary to calculate trajectories. Calculating trajectories is an interesting problem since it relates to what made the ENIAC so interesting at Aberdeen. They were using it for calculating trajectories, unknown to me at the time. We were calculating trajectories by hand at the University of Toronto using a method which is often referred to as the Richardson method. So the whole technique of numerical analysis and numerical computation got to be very intriguing to me. MERTZ: Was this done on a Friden [or] Marchant type calculator? RUBINOFF: MERTZ: This was a War project at the University of Toronto? RUBINOFF: This was a post-War project. It was an outgrowth of a war project on proximity fuse. It was supported by the Canadian Army who were very interested in finding out what made liquid filled shell tumble rather than fly properly when they went through space. -

EULOGY for WILLIS WARE Michael Rich March 28, 2014

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and EDUCATION AND THE ARTS decisionmaking through research and analysis. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from www.rand.org as a public service INFRASTRUCTURE AND of the RAND Corporation. TRANSPORTATION INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY Support RAND SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Browse Reports & Bookstore TERRORISM AND Make a charitable contribution HOMELAND SECURITY For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation corporate publication series. Corporate publications describe or promote RAND divisions and programs, summarize research results, or announce upcoming events. EULOGY FOR WILLIS WARE Michael Rich March 28, 2014 I want to begin by thanking the entire Ware Family for ensuring that all of us who knew and admired Willis Ware have this chance to reflect on his extraordinary life: • Willis’s daughters, Ali and Deb • his sons-in-law, Tom and Ed • his granddaughters, Arielle and Victoria • his great-grandson, Aidan • his brother, Stanley; sister-in-law, Sigrid; and niece, Joanne. -

Building Computers in 1953: JOHNNIAC"

The Computer Museum History Center presents "Building Computers in 1953: JOHNNIAC" Willis Ware Bill Gunning JOHNNIAC Designer JOHNNIAC Project Engineer Paul Armer Mort Bernstein RAND Department Head JOHNNIAC Software Developer 5:30 PM, Tuesday, Sept. 15, 1998 Computer Museum History Center Building 126 Moffett Field Mt. View JOHNNIAC was one of an illustrious group of computers built in the early 1950's, all inspired by the IAS computer designed by John von Neumann at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. Some of these machines were MANIAC (Los Alamos) and ILLIAC (Univ. of Illinois), as well as WEIZAC, AVIDAC, and ORDVAC. JOHNNIAC was built at RAND Corporation in Santa Monica, and named after John von Neumann himself (he "disapproved", but didn't complain too much). This talk will be given in front of JOHNNIAC itself, the actual machine, since it is now part of the Computer Museum History Center at Moffett Field, the world's largest collection of historical computer hardware. JOHNNIAC ran for the first time in March, 1954. It pioneered the development of time shared operating systems with JOSS (the JOHNNIAC Open Shop System). JOSS could support several dozen users with drum swapping -- there were no disk drives then, so no disk swapping, but instead large rotating drums for magnetic storage. JOHNNIAC also inaugurated the commercial use of magnetic core memory, iron doughnuts on wires, which dominated computer memories for the next decade. Among other tasks, JOHNNIAC was also used to develop digitizing tablets for computer input. Our speakers were all working on JOHNNIAC over 40 years ago. -

RAND and the Information Evolution a History in Essays and Vignettes WILLIS H

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS NATIONAL SECURITY The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Learn more about the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation corporate publication series. Corporate publications describe or promote RAND divisions and programs, summarize research results, or announce upcoming events. RAND and the Information Evolution A History in Essays and Vignettes WILLIS H. WARE C O R P O R A T I O N Funding for the publication of this document was provided through a generous gift from Paul Baran, an alumnus of RAND, and support from RAND via its philanthropic donors and income from operations. -

Computer History II

Key Events in the History of Computing II Post World War II 1945 Grace Murray Hopper, working in a temporary World War I building at Harvard University on the Mark II computer, found the first computer bug beaten to death in the jaws of a relay. She glued it into the logbook of the computer and thereafter when the machine stops (frequently) they tell Howard Aiken that they are "debugging" the computer. The very first bug still exists in the National Museum of American History of the Smithsonian Institution. The word bug and the concept of debugging had been used previously, perhaps by Edison, but this was probably the first verification that the concept applied to computers. 14 February 1946 ENIAC was unveiled in Philadelphia. ENIAC represented still a stepping stone towards the true computer, for differently than Babbage, Eckert and Mauchly, although they knew that the machine was not the ultimate in the state-of-the-art technology, completed the construction. ENIAC was programmed through the rewiring the interconnections between the various components and included the capability of parallel computation. ENIAC was later to be modified into a stored program machine, but not before other machines had claimed the claim to be the first true computer. 1946 was the year in which the first computer meeting took place, with the University of Pennsylvania organizing the first of a series of "summer meetings" where scientists from around the world learned about ENIAC and their plans for EDVAC. Among the attendees was Maurice Wilkes from the University of Cambridge who would return to England to build the EDSAC. -

Security in an Insecure Age

Duflock 0 Security in an Insecure Age: Cybersecurity Policy and the Cybersecurity Community in the United States, 1967-1986 Meredith Duflock Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of History, Georgetown University Cybersecurity Advisor: Professor Ben Buchanan History Advisor: Professor David Painter Honors Program Chair: Professor Katherine Benton-Cohen 6 May 2019 Duflock 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………………………… 2 Reference Materials: Acronyms, Organizations, Figures, Terms, Timeline ……………………. 4 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………….. 11 Historiographical review, background, defining key terms. Chapter 1: Birth of the Cybersecurity Community, Mid-1960s to 1973 ………………………. 26 Part 1: Early Conversations and “Security and Privacy in Computer Systems” (1967) 27 Part 2: The Ware Report (1970) .………………………………………………………. 37 Part 3: The First Anderson Report (1972) …………………………………………….. 42 Chapter 2: The Community Develops, Mid-1970s to Early 1980s ……………………………. 49 Part 1: Conferences and Journals .…………………………………………………….. 49 Part 2: Bell-LaPadula .…………………………………………………………………. 55 Chapter 3: Ideas Become Policy, 1982-1986 …………………………………………………... 61 Part 1: The Orange Book (1983) ………………………………………………………. 62 Chapter 4: Computer Fraud Legislation, 1983-1986 …………………………………………... 73 Part 1: Network (In)Security and The Hacking Community .………………………….. 74 Part 2: The 1984 and 1986 Computer Fraud and Abuse Acts ………………………… 78 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………………………... 89 Bibliography ………………………………………………………………………………….... 97 Duflock 2 Acknowledgements Until eighth grade, I hated history. I disliked memorizing useless facts about people long dead and found the tests – almost entirely memorization of names and dates – exhausting and stressful. Eighth grade history was taught by Mrs. Larson, a wonderful woman famous for her strictness (though who could blame her, with a class full of eighth graders). In her classroom, I finally understood why history mattered: it informs how we think of our world. -

Oral History of Akrevoe Emmanouilides, 2008-08-19

Oral History of Akrevoe Emmanouilides Interviewed by: Dag Spicer Recorded: August 19, 2008 Mountain View, California CHM Reference number: X4980.2009 © 2008 Computer History Museum Oral History of Akrevoe Emmanouilides Dag Spicer: Welcome. We're here today. I'm Dag Spicer with the Computer History Museum. I'm here with Akrevoe Emmanou— Akrevoe Emmanouilides: Emmanouilides. Spicer: Emmanouilides. And could you just spell that for us so we have it on camera? Emmanouilides: Of course. My first name is A-k-r-e-v-o-e. My last name is E-m-m-a-n-o-u-i-l-i-d-e-s. And Akrevoe is the Greek word for expensive or precious, and Emmanouilides means the son of Emmanuel. Spicer: So that's a great name, great combination. Thanks for being with us today. I really appreciate that, and especially, you coming to visit us just kind of on a lark last week. You just came by to say hello and we met, and it turned out that you actually were present at some very important times in computer history. And before we get to those, I thought we'd just start out with your early childhood and where you grew up and maybe a bit about your parents and your schooling. Why don't we just start there? Emmanouilides: Fine. I was born in Philadelphia in 1928, September 11th, <laugh> coincidentally, which has become a very important day in our own history. I was raised in Philadelphia. My parents were immigrants; my father from the Ionian island of Lefkas, which is on the western coast of Greece, and my mother was from Turkey, from an area called Marmara. -

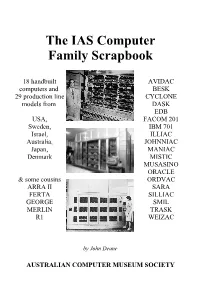

The IAS Computer Family Scrapbook

The IAS Computer Family Scrapbook 18 handbuilt AVIDAC computers and BESK 29 production line CYCLONE models from DASK EDB USA, FACOM 201 Sweden, IBM 701 Israel, ILLIAC Australia, JOHNNIAC Japan, MANIAC Denmark MISTIC MUSASINO ORACLE & some cousins ORDVAC ARRA II SARA FERTA SILLIAC GEORGE SMIL MERLIN TRASK R1 WEIZAC by John Deane AUSTRALIAN COMPUTER MUSEUM SOCIETY The IAS Computer Family Scrapbook by John Deane Front cover: John von Neumann and the IAS Computer (Photo by Alan Richards, courtesy of the Archives of the Institute for Advanced Study), Rand's JOHNNIAC (Rand Corp photo), University of Sydney's SILLIAC (photo courtesy of the University of Sydney Science Foundation for Physics). Back cover: Lawrence Von Tersch surrounded by parts of Michigan State University's MISTIC (photo courtesy of Michigan State University). The “IAS Family” is more formally known as Princeton Class machines (the Institute for Advanced Study is at Princeton, NJ, USA), and they were referred to as JONIACs by Klara von Neumann in her forward to her husband's book The Computer and the Brain. Photograph copyright generally belongs to the institution that built the machine. Text © 2003 John Deane [email protected] Published by the Australian Computer Museum Society Inc PO Box 847, Pennant Hills NSW 2120, Australia Acknowledgments My thanks to Simon Lavington & J.A.N. Lee for your encouragement. A great many people responded to my questions about their machines while I was working on a history of SILLIAC. I have been sent manuals, newsletters, web references, photos, -

New Challenges for the New Year

From the Editors New Challenges for the New Year ou’ve heard from me in this space before, but this is great interest that the RoboCup soc- cer competitions have generated. In my first column as IEEE Security & Privacy’s editor addition to possibly advancing the state of the art, such competitions can in chief. I feel both honored and privileged to have be highly educational and entertain- ing. A few years ago when I asked the opportunity to assume this responsibility. Google cofounder Sergey Brin what Y he had found most beneficial in his CARL E. George Cybenko, as both the driving force behind the magazine’s undergraduate career at the Univer- LANDWEHR sity of Maryland, he pointed to the Editor in Chief creation and its EIC for the first four I’m especially interested in hearing programming competitions in which years, is a hard act to follow. But be- from you about what you like and he had participated. cause he created such a strong base for don’t like in S&P. We can and do While at the US National Science the magazine, I’m hoping it won’t be a monitor the download rates for vari- Foundation, I spent some time trying difficult act to continue. You can ex- ous articles that we print, but those sta- to figure out how to structure a chal- pect the mix of articles, departments, tistics tell only part of the story. This is lenge or a competition that would and special issues on current topics to a volunteer effort, and we depend on help us move beyond our present continue. -

How RAND Invented the Postwar World

How RAND Invented the Postwar World SATELLITES, SYSTEMS ANALYSIS, COMPUTING, THE INTERNET—ALMOST ALL THE DEFINING FEATURES OF THE INFORMATION AGE WERE SHAPED IN PART AT THE RAND CORPORATION BY VIRGINIA CAMPBELL TO SOME FIRST-RATE ANALYTICAL MINDS, HAVING INTELLEC- Centralized, That was the genesis of the original tual elbow room in which to carry out advanced research can decentralized, and “think tank,” Project RAND, the name be a greater lure than money, power, or position. Academic distributed networks, being short for Research and Develop- institutions understand this, as do certain sectors of the cor- from Paul Baran’s ment. (The term think tank was coined porate world. But military organizations, with their emphasis prescient 1964 book. in Britain during World War II and on hierarchy, discipline, and protocol, have traditionally been then imported to the United States to the least likely to provide the necessary freedom. describe RAND’s mission.) The project officially got under way During World War II, however, the Commanding General in December 1945, and in March 1946 RAND was launched as of the U.S. Army Air Forces, H. H. (“Hap”) Arnold, saw crea- a freestanding division within the Douglas Aircraft Com- tive engineers and scientists come up with key inventions such pany of Santa Monica, California (whose founder, David Doug- as radar, the proximity fuze, and, of course, the atomic bomb. las, was a longtime close friend of Hap Arnold). A number of He knew that research and development would be even more other aeronautical enterprises had sprung up or flourished in important in the battles of the future. -

Information Security and Privacy in Network Environments

Information Security and Privacy in Network Environments September 1994 OTA-TCT-606 NTIS order #PB95-109203 GPO stock #052-003-01387-8 Recommended Citation: U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, Information Security and Privacy in Network Environments, OTA-TCT-606 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, September 1994). For Wk by the U.S. Government Prlnflng Office Superintendent of Document\, MiIIl Stop: SSOP, Wti\hlngton, DC 204)2-932/! ISBN O- 16-04!; 188-4 Foreword nformation networks are changing the way we do business, educate our children, deliver government services, and dispense health care. Information technologies are intruding in our lives in both I positive and negative ways. On the positive side, they provide win- dows to rich information resources throughout the world. They provide instantaneous communication of information that can be shared with all who are connected to the network. As businesses and government be- come more dependent on networked computer information, the more vulnerable we are to having private and confidential information fall into the hands of the unintended or unauthorized person. Thus appropriate institutional and technological safeguards are required for a broad range of personal, copyrighted, sensitive, or proprietary information. Other- wise, concerns for the security and privacy of networked information may limit the usefulness and acceptance of the global information infra- structure. This report was prepared in response to a request by the Senate Com- mittee on Governmental Affairs and the House Subcommittee on Tele- communications and Finance. The report focuses on policy issues in three areas: 1 ) national cryptography policy, including federal informa- tion processing standards and export controls; 2) guidance on safeguard- ing unclassified information in federal agencies; and 3) legal issues and information security, including electronic commerce, privacy, and intel- lectual property. -

The Research and Development (RAND) Corporation Videohistory Collection, 1987-1990

The Research and Development (RAND) Corporation Videohistory Collection, 1987-1990 Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction....................................................................................................................... 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Aerial Reconnaissance Photography........................................................ 4 Series 2: RAND Culture........................................................................................... 7 Series 3: Computers................................................................................................ 9 The Research and Development (RAND) Corporation Videohistory Collection https://siarchives.si.edu/collections/siris_arc_217704